Base-Compositional Biases and the Bat Problem. III. the Question of Microchiropteran Monophyly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Volume 41, 2000

BAT RESEARCH NEWS Volume 41 : No. 1 Spring 2000 I I BAT RESEARCH NEWS Volume 41: Numbers 1–4 2000 Original Issues Compiled by Dr. G. Roy Horst, Publisher and Managing Editor of Bat Research News, 2000. Copyright 2011 Bat Research News. All rights reserved. This material is protected by copyright and may not be reproduced, transmitted, posted on a Web site or a listserve, or disseminated in any form or by any means without prior written permission from the Publisher, Dr. Margaret A. Griffiths. The material is for individual use only. Bat Research News is ISSN # 0005-6227. BAT RESEARCH NEWS Volume41 Spring 2000 Numberl Contents Resolution on Rabies Exposure Merlin Tuttle and Thomas Griffiths o o o o eo o o o • o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o 0 o o o o o o o o o o o 0 o o o 1 E - Mail Directory - 2000 Compiled by Roy Horst •••• 0 ...................... 0 ••••••••••••••••••••••• 2 ,t:.'. Recent Literature Compiled by :Margaret Griffiths . : ....••... •"r''• ..., .... >.•••••• , ••••• • ••< ...... 19 ,.!,..j,..,' ""o: ,II ,' f 'lf.,·,,- .,'b'l: ,~··.,., lfl!t • 0'( Titles Presented at the 7th Bat Researc:b Confei'ebee~;Moscow :i'\prill4-16~ '1999,., ..,, ~ .• , ' ' • I"',.., .. ' ""!' ,. Compiled by Roy Horst .. : .......... ~ ... ~· ....... : :· ,"'·~ .• ~:• .... ; •. ,·~ •.•, .. , ........ 22 ·.t.'t, J .,•• ~~ Letters to the Editor 26 I ••• 0 ••••• 0 •••••••••••• 0 ••••••• 0. 0. 0 0 ••••••• 0 •• 0. 0 •••••••• 0 ••••••••• 30 News . " Future Meetings, Conferences and Symposium ..................... ~ ..,•'.: .. ,. ·..; .... 31 Front Cover The illustration of Rhinolophus ferrumequinum on the front cover of this issue is by Philippe Penicaud . from his very handsome series of drawings representing the bats of France. -

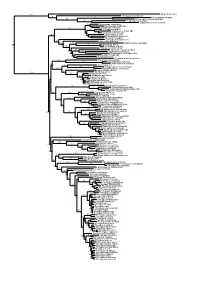

Figs1 ML Tree.Pdf

100 Megaderma lyra Rhinopoma hardwickei 71 100 Rhinolophus creaghi 100 Rhinolophus ferrumequinum 100 Hipposideros armiger Hipposideros commersoni 99 Megaerops ecaudatus 85 Megaerops niphanae 100 Megaerops kusnotoi 100 Cynopterus sphinx 98 Cynopterus horsfieldii 69 Cynopterus brachyotis 94 50 Ptenochirus minor 86 Ptenochirus wetmorei Ptenochirus jagori Dyacopterus spadiceus 99 Sphaerias blanfordi 99 97 Balionycteris maculata 100 Aethalops alecto 99 Aethalops aequalis Thoopterus nigrescens 97 Alionycteris paucidentata 33 99 Haplonycteris fischeri 29 Otopteropus cartilagonodus Latidens salimalii 43 88 Penthetor lucasi Chironax melanocephalus 90 Syconycteris australis 100 Macroglossus minimus 34 Macroglossus sobrinus 92 Boneia bidens 100 Harpyionycteris whiteheadi 69 Harpyionycteris celebensis Aproteles bulmerae 51 Dobsonia minor 100 100 80 Dobsonia inermis Dobsonia praedatrix 99 96 14 Dobsonia viridis Dobsonia peronii 47 Dobsonia pannietensis 56 Dobsonia moluccensis 29 Dobsonia anderseni 100 Scotonycteris zenkeri 100 Casinycteris ophiodon 87 Casinycteris campomaanensis Casinycteris argynnis 99 100 Eonycteris spelaea 100 Eonycteris major Eonycteris robusta 100 100 Rousettus amplexicaudatus 94 Rousettus spinalatus 99 Rousettus leschenaultii 100 Rousettus aegyptiacus 77 Rousettus madagascariensis 87 Rousettus obliviosus Stenonycteris lanosus 100 Megaloglossus woermanni 100 91 Megaloglossus azagnyi 22 Myonycteris angolensis 100 87 Myonycteris torquata 61 Myonycteris brachycephala 33 41 Myonycteris leptodon Myonycteris relicta 68 Plerotes anchietae -

Index of Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Vol. 9. Bats

Index of Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Vol. 9. Bats A agnella, Kerivoula 901 Anchieta’s Bat 814 aquilus, Glischropus 763 Aba Leaf-nosed Bat 247 aladdin, Pipistrellus pipistrellus 771 Anchieta’s Broad-faced Fruit Bat 94 aquilus, Platyrrhinus 567 Aba Roundleaf Bat 247 alascensis, Myotis lucifugus 927 Anchieta’s Pipistrelle 814 Arabian Barbastelle 861 abae, Hipposideros 247 alaschanicus, Hypsugo 810 anchietae, Plerotes 94 Arabian Horseshoe Bat 296 abae, Rhinolophus fumigatus 290 Alashanian Pipistrelle 810 ancricola, Myotis 957 Arabian Mouse-tailed Bat 164, 170, 176 abbotti, Myotis hasseltii 970 alba, Ectophylla 466, 480, 569 Andaman Horseshoe Bat 314 Arabian Pipistrelle 810 abditum, Megaderma spasma 191 albatus, Myopterus daubentonii 663 Andaman Intermediate Horseshoe Arabian Trident Bat 229 Abo Bat 725, 832 Alberico’s Broad-nosed Bat 565 Bat 321 Arabian Trident Leaf-nosed Bat 229 Abo Butterfly Bat 725, 832 albericoi, Platyrrhinus 565 andamanensis, Rhinolophus 321 arabica, Asellia 229 abramus, Pipistrellus 777 albescens, Myotis 940 Andean Fruit Bat 547 arabicus, Hypsugo 810 abrasus, Cynomops 604, 640 albicollis, Megaerops 64 Andersen’s Bare-backed Fruit Bat 109 arabicus, Rousettus aegyptiacus 87 Abruzzi’s Wrinkle-lipped Bat 645 albipinnis, Taphozous longimanus 353 Andersen’s Flying Fox 158 arabium, Rhinopoma cystops 176 Abyssinian Horseshoe Bat 290 albiventer, Nyctimene 36, 118 Andersen’s Fruit-eating Bat 578 Arafura Large-footed Bat 969 Acerodon albiventris, Noctilio 405, 411 Andersen’s Leaf-nosed Bat 254 Arata Yellow-shouldered Bat 543 Sulawesi 134 albofuscus, Scotoecus 762 Andersen’s Little Fruit-eating Bat 578 Arata-Thomas Yellow-shouldered Talaud 134 alboguttata, Glauconycteris 833 Andersen’s Naked-backed Fruit Bat 109 Bat 543 Acerodon 134 albus, Diclidurus 339, 367 Andersen’s Roundleaf Bat 254 aratathomasi, Sturnira 543 Acerodon mackloti (see A. -

Molecular Phylogenetic Relationship Between and Within the Fruit

Journal of American Science, 2011;7(10) http://www.americanscience.org Molecular Phylogenetic Relationship Between and Within the Fruit Bat (Rousettus Aegyptiacus) and the Lesser Tailed Bat (Rhinopoma Hardwickei) Deduced From RAPD-PCR Analysis Ramadan A. M. Ali Department of Zoology, College for Women, Ain Shams University, Cairo, Egypt [email protected] Abstract: The RAPD-PCR in the present study was used to determine the genetic variation within and among two Egyptian bat species, Rousettus aegyptiacus and Rhinopoma hardwickei. The animals were captured from one locality at Giza governorate, Egypt. A total of 39 bands were amplified by the three primers OPAO2, OPAO8 and OPCO3 with an average 13 bands per primer at molecular weights ranged from 1409 to 107 bp. The polymorphic loci between both species were 34 with percentage 87.18 %. The numbers of monomorphic bands in Rousettus aegyptiacus aegyptiacus and Rhinopoma hardwickei arabium were 14 and 9 bands, respectively. The two species are sharing 5 (12.8 %) monomorphic bands. The similarity coefficients value between the two bat species was ranged from 0.353 to 0.500 with an average of 0.404 (40.4%). Dendrogram showed that, the two bats genotypes are separated from each other into two clusters and more variation among members of Rhinopoma hardwickei arabium was observed in comparison to those of Rousettus aegyptiacus aegyptiacus. It is concluded that, the similarity coefficient value between the two bat species indicates that, the two bat species may have the same origin but are not identical and separated into two clusters. [Ramadan A. M. Ali Molecular Phylogenetic Relationship Between and Within the Fruit Bat (Rousettus Aegyptiacus) and the Lesser Tailed Bat (Rhinopoma Hardwickei) Deduced From Rapd-Pcr Analysis] Journal of American Science 2011; 7(10): 678-687].(ISSN: 1545-1003). -

Form, Function, and Evolution in Skulls and Teeth of Bats

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Papers in Natural Resources Natural Resources, School of May 1998 Form, Function, and Evolution in Skulls and Teeth of Bats Patricia W. Freeman University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/natrespapers Part of the Natural Resources and Conservation Commons Freeman, Patricia W., "Form, Function, and Evolution in Skulls and Teeth of Bats" (1998). Papers in Natural Resources. 9. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/natrespapers/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Natural Resources, School of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Papers in Natural Resources by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. 9 Form, Function, and Evolution in Skulls and Teeth of Bats PATRICIA W FREEMAN Bats provide a model system for tracking change from the stylar shelves and elongated skulls with larger brain vol- primitive mammalian tooth pattern to patterns indicating umes and external ears than their insectivorous relatives. As the more-derived food habits of carnivory, nectarivory, in terrestrial mammals, however, there is no clear distinc- frugivory, and sanguinivory. Whereas microchiropteran tion between insectivorous and carnivorous species (Savage bats show all these transitions, megachiropterans illustrate 1977; Freeman 1984). Microchiropteran nectarivores are an alternative pattern concerned only with frugivory and also on a continuum with insectivores but are characteris- nectarivory. In rnicrochiropterans, it is likely that carnivory tically long-snouted with large canines and diminutive post- nectarivory, frugivory, and sanguinivory are all derived canine teeth (Freeman 1995). -

The Evolution of Echolocation in Bats: a Comparative Approach

The evolution of echolocation in bats: a comparative approach Alanna Collen A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy from the Department of Genetics, Evolution and Environment, University College London. November 2012 Declaration Declaration I, Alanna Collen (née Maltby), confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, this is indicated in the thesis, and below: Chapter 1 This chapter is published in the Handbook of Mammalian Vocalisations (Maltby, Jones, & Jones) as a first authored book chapter with Gareth Jones and Kate Jones. Gareth Jones provided the research for the genetics section, and both Kate Jones and Gareth Jones providing comments and edits. Chapter 2 The raw echolocation call recordings in EchoBank were largely made and contributed by members of the ‘Echolocation Call Consortium’ (see full list in Chapter 2). The R code for the diversity maps was provided by Kamran Safi. Custom adjustments were made to the computer program SonoBat by developer Joe Szewczak, Humboldt State University, in order to select echolocation calls for measurement. Chapter 3 The supertree construction process was carried out using Perl scripts developed and provided by Olaf Bininda-Emonds, University of Oldenburg, and the supertree was run and dated by Olaf Bininda-Emonds. The source trees for the Pteropodidae were collected by Imperial College London MSc student Christina Ravinet. Chapter 4 Rob Freckleton, University of Sheffield, and Luke Harmon, University of Idaho, helped with R code implementation. 2 Declaration Chapter 5 Luke Harmon, University of Idaho, helped with R code implementation. Chapter 6 Joseph W. -

Meseret Chane Alemu Advisor

SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES DEPARTMENT OF ZOOLOGICAL SCIENCES Effect of Anthropogenic Habitat Modification on Behavioural Ecology of Boutourlini's Blue Monkey (Cercopithecus mitis boutourlinii Giglioli, 1887) in Hamuma Coffee Forest, Southwestern Ethiopia By: Meseret Chane Alemu Advisor: Professor Afework Bekele Addis Ababa, Ethiopia June 2020 ADDIS ABABA UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES DEPARTMENT OF ZOOLOGICAL SCIENCES Effect of Anthropogenic Habitat Modification on Behavioural Ecology of Boutourlini's Blue Monkey (Cercopithecus mitis boutourlinii Giglioli, 1887) in Hamuma Coffee Forest, Southwestern Ethiopia By: Meseret Chane Alemu A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies of the Addis Ababa University, Department of Zoological Sciences, in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Biology (Ecological and Systematic Zoology) Approved by Examining Committee: Name Signature 1. Professor Afework Bekele (Advisor)_____________________ 2. Prof./Dr. ____________________ (Examiner) ____________________ 3. Prof./Dr. ____________________ (Examiner) _____________________ 4. Dr. Bezawork Afework (Chairperson) ___________________ I hereby declare that this thesis, entitled: “Effect of Anthropogenic Habitat Modification on Behavioural Ecology of Boutourlini's Blue Monkey (Cercopithecus mitis boutourlinii Giglioli, 1887) in Hamuma Coffee Forest, Southwestern Ethiopia” has been composed entirely by myself and has not been submitted for any other degree or qualification. The work complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality and all sources of information have been specifically acknowledged. Meseret Chane: Signature __________________ Date ____________________ ABSTRACT Effect of Anthropogenic Habitat Modification on Behavioural Ecology of Boutourlini's Blue Monkey (Cercopithecus mitis boutourlinii Giglioli, 1887) in Hamuma Coffee Forest, Southwestern Ethiopia Meseret Chane Alemu. -

Colugos: Obscure Mammals Glide Into the Evolutionary Limelight Robert D Martin

BioMed Central Minireview Colugos: obscure mammals glide into the evolutionary limelight Robert D Martin Address: Department of Anthropology, The Field Museum, Chicago, IL 60605-2496, USA. Email: [email protected] Published: 1 May 2008 Journal of Biology 2008, 7:13 (doi:10.1186/jbiol74) The electronic version of this article is the complete one and can be found online at http://jbiol.com/content/7/4/13 © 2008 BioMed Central Ltd Abstract Substantial molecular evidence indicates that tree-shrews, colugos and primates cluster together on the mammalian phylogenetic tree. Previously, a sister-group relationship between colugos and primates seemed likely. A new study of colugo chromosomes indicates instead an affinity between colugos and tree-shrews. Colugos, constituting the obscure and tiny order Dermop- shrews, tree-shrews, colugos, bats and primates. However, tera, are gliding mammals confined to evergreen tropical Simpson’s ensuing influential classification of mammals [1] rainforests of South-East Asia. There are two extant species, rejected this assemblage. Subsequently, prompted by Butler now placed in separate genera: Galeopterus variegatus [4], the superorder Archonta was progressively resuscitated, (Malayan colugo, formerly known as Cynocephalus variegatus) although most authors emphatically excluded elephant- and Cynocephalus volans (Philippine colugo). Their most shrews (for example [5,6]). A quite recent major classifi- obvious hallmark is a gliding membrane (patagium) cation of mammals [7] united tree-shrews, colugos, bats surrounding almost the entire body margin. Colugos are and primates in the grand order Archonta. also called ‘flying lemurs’, but - as Simpson aptly noted [1] - they “are not lemurs and cannot fly”. They differ from other This whole topic has been reinvigorated by molecular gliding mammals (certain rodents and marsupials) in that evidence indicating that tree-shrews, colugos and primates, the patagium also extends between the hind limbs and the at least, may be quite closely related. -

NEOTROPICAL Primates VOLUME 9 NUMBER 3 DECEMBER 2001

ISSN 1413-4703 NEOTROPICAL primates VOLUME 9 NUMBER 3 DECEMBER 2001 A Journal and Newsletter of the Neotropical Section of the IUCN/SSC Primate Specialist Group Editors: Anthony B. Rylands and Ernesto Rodríguez-Luna PSG Chairman: Russell A. Mittermeier PSG Deputy Chairmen: Anthony B. Rylands and William R. Konstant Neotropical Primates A Journal and Newsletter of the Neotropical Section of the IUCN/SSC Primate Specialist Group Center for Applied Biodiversity Science S Conservation International T 1919 M. St. NW, Suite 600, Washington, DC 20036, USA t ISSN 1413-4703 w Abbreviation: Neotrop. Primates a Editors t Anthony B. Rylands, Center for Applied Biodiversity Science, Conservation International, Washington, DC Ernesto RodrÌguez-Luna, Universidad Veracruzana, Xalapa, Mexico S Assistant Editor Jennifer Pervola, Center for Applied Biodiversity Science, Conservation International, Washington, DC P P Editorial Board Hannah M. Buchanan-Smith, University of Stirling, Stirling, Scotland, UK B Adelmar F. Coimbra-Filho, Academia Brasileira de CiÍncias, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil D Liliana CortÈs-Ortiz, Universidad Veracruzana, Xalapa, Mexico < Carolyn M. Crockett, Regional Primate Research Center, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA t Stephen F. Ferrari, Universidade Federal do Par·, BelÈm, Brazil Eckhard W. Heymann, Deutsches Primatenzentrum, Gˆttingen, Germany U William R. Konstant, Conservation International, Washington, DC V Russell A. Mittermeier, Conservation International, Washington, DC e Marta D. Mudry, Universidad de Buenos Aires, Argentina Hor·cio Schneider, Universidade Federal do Par·, BelÈm, Brazil Karen B. Strier, University of Wisconsin, Madison, Wisconsin, USA C Maria EmÌlia Yamamoto, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Natal, Brazil M Primate Specialist Group a Chairman Russell A. Mittermeier Deputy Chairs Anthony B. -

Eutheria (Placental Mammals) Thought of As More Primitive

Eutheria (Placental Introductory article Mammals) Article Contents . Introduction J David Archibald, San Diego State University, San Diego, California, USA . Basic Design . Taxonomic and Ecological Diversity Eutheria includes one of three major clades of mammals, the extant members of which are . Fossil History and Distribution referred to as placentals. Phylogeny Introduction doi: 10.1038/npg.els.0004123 Eutheria (or Placentalia) is the most taxonomically diverse each. Except for placentals that have supernumerary teeth of three branches or clades of mammals, the other two (e.g. some whales, armadillos, etc.), in extant placentals, the being Metatheria (or Marsupialia) and Prototheria (or number of teeth is at most three upper and lower incisors, Monotremata). When named by Gill in 1872, Eutheria in- one upper and lower canine, four upper and lower premo- cluded both marsupials and placentals. It was Huxley in lars and three upper and lower molars. Pigs retain this pat- 1880 who recognized Eutheria basically as used today to tern, and except for one fewer upper molar, a domestic dog include only placentals. McKenna and Bell in their Clas- does as well. Compared to reptiles, mammals have fewer sification of Mammals published in 1997, chose to use Pla- skull bones through fusion and loss, although bones are centalia rather than Eutheria to avoid the confusion of variously emphasized in each of the three major mammalian what taxa should be included in Eutheria. Others such as taxa. See also: Digestive system of mammals; Ingestion in Rougier have used Eutheria and Placentalia in the sense mammals; Mesozoic mammals; Reptilia (reptiles) used here. Placentalia includes all extant placentals and Physiologically, mammals are all endotherms with var- their most recent common ancestor. -

Teeling2009chap78.Pdf

Bats (Chiroptera) Emma C. Teeling oldest bat fossils (~55 Ma) and is considered a microbat; UCD School of Biology and Environmental Science, Science Center however, the majority of the bat fossil record is fragmen- West, University College Dublin, Belfi eld, Dublin 4, Ireland (emma. tary and missing key species (6, 7). Here I review the rela- [email protected]) tionships and divergence times of the extant families of bats. Abstract Traditionally bats have been divided into two super- ordinal groups: Megachiroptera and Microchiroptera Bats are grouped into 17–18 families (>1000 species) within (see 8, 9 for reviews). Megachiroptera was consid- the mammalian Order Chiroptera. Recent phylogenetic ered basal and contained the Old World megabat fam- analyses of molecular data have reclassifi ed Chiroptera at ily Pteropodidae, whereas Microchiroptera contained the interfamilial level. Traditionally, the non-echolocating the 17 microbat families (8, 9). Although this division megabats (Pteropodidae) have been considered to be the was based mainly on morphological and paleonto- earliest diverging lineage of living bats; however, they are logical data, it highlighted the diB erence in mode of now found to be the closest relatives of the echolocating sensory perception between megabats and microbats. rhinolophoid microbats. Four major groups of echolocating Because all microbats are capable of sophisticated laryn- microbats are supported: rhinolophoids, emballonuroids, geal echolocation whereas megabats are not (5), it was vespertilionoids, and noctilionoids. The timetree suggests believed that laryngeal echolocation had a single origin that the earliest divergences among bats occurred ~64 in the lineage leading to microbats (10). 7 e 17 families million years ago (Ma) and that the four major microbat of microbats have been subsequently divided into two lineages were established by 50 Ma. -

Biogeography and Phylogeny of the Eutheria

FAUNA of AUSTRALIA 36. BIOGEOGRAPHY AND PHYLOGENY OF EUTHERIA G.M. MCKAY, J.H. CALABY & L.S. HALL 1 36. BIOGEOGRAPHY AND PHYLOGENY OF EUTHERIA 2 36. BIOGEOGRAPHY AND PHYLOGENY OF EUTHERIA INTRODUCTION In considering the biogeography and phylogeny of the eutherian mammals in Australia, a distinction must be made between those groups which invaded the continent prior to the 18th Century and those that have been deliberately or inadvertently introduced since then. For the latter group, the worldwide distribution and fossil history is essentially irrelevant except that many species have a long association with humans as either domesticated animals or commensals. In this chapter, we will address the more general questions of the origins and affinities of the native Australian eutherians. For details of the biogeography, fossil history and affinities of the introduced mammals, the reader should refer to the family accounts (Chapters 44–46, 54, 55, 58–62). Any examination of the phylogeny of a group must consider two main lines of evidence: the fossil record and the study of living forms. Morphological studies can be made on both living and fossil forms and such studies, particularly of skeletal and dental characters, have traditionally formed the basis for phylogenetic reconstruction in the Mammalia. In recent years there has been an increase in biochemical and molecular studies on living species which, with a very few exceptions, cannot be compared to extinct species. To date, only a relatively few species of living mammals have been studied adequately using molecular techniques, but attempts are being made to reconcile the biochemical data with the traditional morphological studies (Shoshani 1986; McKenna 1987).