Master's Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Predicted the Impacts of Climate Change and Extreme-Weather Events on the Future

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.05.13.443960; this version posted May 14, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Predicted the impacts of climate change and extreme-weather events on the future distribution of fruit bats in Australia Vishesh L. Diengdoh1, e: [email protected], ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000- 0002-0797-9261 Stefania Ondei1 - e: [email protected] Mark Hunt1, 3 - e: [email protected] Barry W. Brook1, 2 - e: [email protected] 1School of Natural Sciences, University of Tasmania, Private Bag 55, Hobart TAS 7005 Australia 2ARC Centre of Excellence for Australian Biodiversity and Heritage, Australia 3National Centre for Future Forest Industries, Australia Corresponding Author: Vishesh L. Diengdoh Acknowledgements We thank John Clarke and Vanessa Round from Climate Change in Australia (https://www.climatechangeinaustralia.gov.au/)/ Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) for providing the data on extreme weather events. This work was supported by the Australian Research Council [grant number FL160100101]. Conflict of Interest None. Author Contributions bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.05.13.443960; this version posted May 14, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. -

A Timeline of Significant Events in the Development of North American Mammalogy

SpecialSpecial PublicationsPublications MuseumMuseum ofof TexasTexas TechTech UniversityUniversity NumberNumber xx66 21 Novemberxx XXXX 20102017 A Timeline of SignificantTitle Events in the Development of North American Mammalogy Molecular Biology Structural Biology Biochemistry Microbiology Genomics Bioinformatics and Computational Biology Computer Science Statistics Physical Chemistry Information Technology Mathematics David J. Schmidly, Robert D. Bradley, Lisa C. Bradley, and Richard D. Stevens Front cover: This figure depicts a chronological presentation of some of the significant events, technological breakthroughs, and iconic personalities in the history of North American mammalogy. Red lines and arrows depict the chronological flow (i.e., top row – read left to right, middle row – read right to left, and third row – read left to right). See text and tables for expanded interpretation of the importance of each person or event. Top row: The first three panels (from left) are associated with the time period entitled “The Emergence Phase (16th‒18th Centuries)” – Mark Catesby’s 1748 map of Carolina, Florida, and the Bahama Islands, Thomas Jefferson, and Charles Willson Peale; the next two panels represent “The Discovery Phase (19th Century)” – Spencer Fullerton Baird and C. Hart Merriam. Middle row: The first two panels (from right) represent “The Natural History Phase (1901‒1960)” – Joseph Grinnell and E. Raymond Hall; the next three panels (from right) depict “The Theoretical and Technological Phase (1961‒2000)” – illustration of Robert H. MacArthur and Edward O. Wilson’s theory of island biogeography, karyogram depicting g-banded chromosomes, and photograph of electrophoretic mobility of proteins from an allozyme analysis. Bottom row: These four panels (from left) represent the “Big Data Phase (2001‒present)” – chromatogram illustrating a DNA sequence, bioinformatics and computational biology, phylogenetic tree of mammals, and storage banks for a supercomputer. -

Seasonal Shedding of Coronaviruses in Straw-Colored Fruit Bats at Urban Roosts in Africa

Seasonal Shedding of Coronaviruses in Straw-colored Fruit Bats at Urban Roosts in Africa The adaptation of bats (order Chiroptera) to use and For these reasons, we assessed the seasonality of occupy human dwellings across the planet has created coronavirus (CoV) shedding by the straw-colored intensive bat-human interfaces. Because bats provide fruit bat (Eidolon helvum) by passively collecting 97 important ecosystem services and also host and shed fecal samples on a monthly basis during a entire year zoonotic viruses, these interfaces represent a double in two urban colonies: Accra, Ghana (West Africa) challenge: i) the conservation of bats and their services and Morogoro, Tanzania (East Africa; Fig 1). Sampling and ii) the prevention of viral spillover. collection was conducted under the same trees during Many species of bats have evolved a seasonal life the study period. This species of fruit bat shows a single history that has resulted in the development of specific birth pulse during the year, its colonies show spectacular reproductive and foraging activities during distinctive periodical changes in size, and similarly to other tree- periods of the year. For example, many species mate, roosting megabats, several roosts are located in busy give birth, and nurse during particular and predictable urban centers across sub-Saharan Africa. Moreover, times of the year. Moreover, bat migration can produce we concomitantly collected data on the roost sizes predictable variations in colony sizes during a typical and precipitation levels over time, and we established year, from a complete absence of bats to the aggregation the reproductive periods through the year (birth of millions of individuals depending on the season. -

A Recent Bat Survey Reveals Bukit Barisan Selatan Landscape As A

A Recent Bat Survey Reveals Bukit Barisan Selatan Landscape as a Chiropteran Diversity Hotspot in Sumatra Author(s): Joe Chun-Chia Huang, Elly Lestari Jazdzyk, Meyner Nusalawo, Ibnu Maryanto, Maharadatunkamsi, Sigit Wiantoro, and Tigga Kingston Source: Acta Chiropterologica, 16(2):413-449. Published By: Museum and Institute of Zoology, Polish Academy of Sciences DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3161/150811014X687369 URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.3161/150811014X687369 BioOne (www.bioone.org) is a nonprofit, online aggregation of core research in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences. BioOne provides a sustainable online platform for over 170 journals and books published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/page/terms_of_use. Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. Acta Chiropterologica, 16(2): 413–449, 2014 PL ISSN 1508-1109 © Museum and Institute of Zoology PAS doi: 10.3161/150811014X687369 A recent -

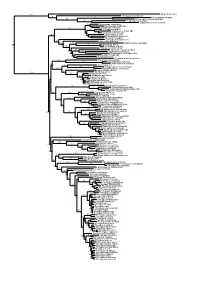

Figs1 ML Tree.Pdf

100 Megaderma lyra Rhinopoma hardwickei 71 100 Rhinolophus creaghi 100 Rhinolophus ferrumequinum 100 Hipposideros armiger Hipposideros commersoni 99 Megaerops ecaudatus 85 Megaerops niphanae 100 Megaerops kusnotoi 100 Cynopterus sphinx 98 Cynopterus horsfieldii 69 Cynopterus brachyotis 94 50 Ptenochirus minor 86 Ptenochirus wetmorei Ptenochirus jagori Dyacopterus spadiceus 99 Sphaerias blanfordi 99 97 Balionycteris maculata 100 Aethalops alecto 99 Aethalops aequalis Thoopterus nigrescens 97 Alionycteris paucidentata 33 99 Haplonycteris fischeri 29 Otopteropus cartilagonodus Latidens salimalii 43 88 Penthetor lucasi Chironax melanocephalus 90 Syconycteris australis 100 Macroglossus minimus 34 Macroglossus sobrinus 92 Boneia bidens 100 Harpyionycteris whiteheadi 69 Harpyionycteris celebensis Aproteles bulmerae 51 Dobsonia minor 100 100 80 Dobsonia inermis Dobsonia praedatrix 99 96 14 Dobsonia viridis Dobsonia peronii 47 Dobsonia pannietensis 56 Dobsonia moluccensis 29 Dobsonia anderseni 100 Scotonycteris zenkeri 100 Casinycteris ophiodon 87 Casinycteris campomaanensis Casinycteris argynnis 99 100 Eonycteris spelaea 100 Eonycteris major Eonycteris robusta 100 100 Rousettus amplexicaudatus 94 Rousettus spinalatus 99 Rousettus leschenaultii 100 Rousettus aegyptiacus 77 Rousettus madagascariensis 87 Rousettus obliviosus Stenonycteris lanosus 100 Megaloglossus woermanni 100 91 Megaloglossus azagnyi 22 Myonycteris angolensis 100 87 Myonycteris torquata 61 Myonycteris brachycephala 33 41 Myonycteris leptodon Myonycteris relicta 68 Plerotes anchietae -

Bat Count 2003

BAT COUNT 2003 Working to promote the long term, sustainable conservation of globally threatened flying foxes in the Philippines, by developing baseline population information, increasing public awareness, and training students and protected area managers in field monitoring techniques. 1 A Terminal Report Submitted by Tammy Mildenstein1, Apolinario B. Cariño2, and Samuel Stier1 1Fish and Wildlife Biology, University of Montana, USA 2Silliman University and Mt. Talinis – Twin Lakes Federation of People’s Organizations, Diputado Extension, Sibulan, Negros Oriental, Philippines Photo by: Juan Pablo Moreiras 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Large flying foxes in insular Southeast Asia are the most threatened of the Old World fruit bats due to deforestation, unregulated hunting, and little conservation commitment from local governments. Despite the fact they are globally endangered and play essential ecological roles in forest regeneration as seed dispersers and pollinators, there have been only a few studies on these bats that provide information useful to their conservation management. Our project aims to promote the conservation of large flying foxes in the Philippines by providing protected area managers with the training and the baseline information necessary to design and implement a long-term management plan for flying foxes. We focused our efforts on the globally endangered Philippine endemics, Acerodon jubatus and Acerodon leucotis, and the bats that commonly roost with them, Pteropus hypomelanus, P. vampyrus lanensis, and P. pumilus which are thought to be declining in the Philippines. Local participation is an integral part of our project. We conducted the first national training workshop on flying fox population counts and conservation at the Subic Bay area. -

ANTIQUITY 2008 (In Press) an Unexpected, Stripe-Faced Flying Fox in Ice Age Rock Art of Australia's Kimberley. “Jack” Pett

ANTIQUITY 2008 (in press) An Unexpected, Stripe-faced Flying Fox in Ice Age Rock Art of Australia’s Kimberley. “Jack” Pettigrew, Marilyn Nugent, Anscar McPhee, Josh Wallman Bradshaw rock art of northern Australia enjoys continuing controversy concerning what community painted them and how to interpret the images (Roy 2002). The keen observation and accurate depictions of the natural world shown here, as well as the extraordinary longevity of the stains used, all tend to support the side of the controversy that posits a distinct cultural entity. We describe a painting unmistakably depicting flying foxes with features not found in bats presently found in Australia. Thermoluminescence dating of wasp nest overlying the art suggests an ice age migration to Australia, either of the bats or of the artists who painted them, a more likely scenario biologically than younger dates. The bat depictions were found on a sandstone wall protected by overhangs, near Kalumburu (14.30 °S; 126.64 °E), amongst other walls showing characteristic Bradshaw art (Walsh 2002). The depiction shows eight roosting megabats (flying foxes, Family Pteropodidae, sub-Order Megachiroptera) hanging from a slender branch, or more likely, a vine (Figs 1,2). Each bat has a distinctive white facial stripe and pale belly (Fig. 3). Figure1. White-striped flying foxes depicted in Bradshaw rock art at Kalumburu, in the Kimberley of Western Australia. Figure 2. Extension, to the left, of the same depicted group of shown in Fig. 1, with which there is some overlap. Dating: The indelible inks used in Bradshaw art penetrate more than a millimetre into the sandstone but have resisted all attempts so far to date them directly, with a number of different estimates of their age (Michaelson and Ebersole 2000). -

The Philippine Flying Foxes, Acerodon Jubatus and Pteropus Vampyrus Lanensis

Journal of Mammalogy, 86(4):719- 728, 2005 DIETARY HABITS OF THE WORLD’S LARGEST BATS: THE PHILIPPINE FLYING FOXES, ACERODON JUBATUS AND PTEROPUS VAMPYRUS LANENSIS Sam C. Stier* and Tammy L. M ildenstein College of Forestry and Conservation, University of Montana, Missoula, MT 59802, USA The endemic and endangered golden- crowned flying fox (Acerodon jubatus) coroosts with the much more common and widespread giant Philippine fmit bat (Pteropus vampyrus ianensis) in lowland dipterocarp forests throughout the Philippine Islands. The number of these mixed roost- colonies and the populations of flying foxes in them have declined dramatically in the last century. We used fecal analysis, interviews of bat hunters, and personal observations to describe the dietary habits of both bat species at one of the largest mixed roosts remaining, near Subic Bay, west- central Luzon. Dietary items were deemed “important” if used consistently on a seasonal basis or throughout the year, ubiquitously throughout the population, and if they were of clear nutritional value. Of the 771 droppings examined over a 2.5 -year period (1998-2000), seeds from Ficus were predominant in the droppings of both species and met these criteria, particularly hemiepiphytic species (41% of droppings of A. jubatus) and Ficus variegata (34% of droppings of P. v. ianensis and 22% of droppings of A. jubatus). Information from bat hunter interviews expanded our knowledge of the dietary habits of both bat species, and corroborated the fecal analyses and personal observations. Results from this study suggest that A. jubatus is a forest obligate, foraging on fruits and leaves from plant species restricted to lowland, mature natural forests, particularly using a small subset of hemiepiphytic and other Ficus species throughout the year. -

Conventional Wisdom on Roosting Behaviour of Australian

Conventional wisdom on roosting behaviour of Australian flying foxes - a critical review, and evaluation using new data Tamika Lunn1, Peggy Eby2, Remy Brooks1, Hamish McCallum1, Raina Plowright3, Maureen Kessler4, and Alison Peel1 1Griffith University 2University of New South Wales 3Montana State University 4Montana State University System April 12, 2021 Abstract 1. Fruit bats (Family: Pteropodidae) are animals of great ecological and economic importance, yet their populations are threatened by ongoing habitat loss and human persecution. A lack of ecological knowledge for the vast majority of Pteropodid bat species presents additional challenges for their conservation and management. 2. In Australia, populations of flying-fox species (Genus: Pteropus) are declining and management approaches are highly contentious. Australian flying-fox roosts are exposed to management regimes involving habitat modification, either through human-wildlife conflict management policies, or vegetation restoration programs. Details on the fine-scale roosting ecology of flying-foxes are not sufficiently known to provide evidence-based guidance for these regimes and the impact on flying-foxes of these habitat modifications is poorly understood. 3. We seek to identify and test commonly held understandings about the roosting ecology of Australian flying-foxes to inform practical recommendations and guide and refine management practices at flying-fox roosts. 4. We identify 31 statements relevant to understanding of flying-fox roosting structure, and synthesise these in the context of existing literature. We then contribute contemporary data on the fine-scale roosting structure of flying-fox species in south-eastern Queensland and north- eastern New South Wales, presenting a 13-month dataset from 2,522 spatially referenced roost trees across eight sites. -

Final Report on the Project

BP Conservation Programme (CLP) 2005 PROJECT NO. 101405 - BRONZE AWARD WINNER ECOLOGY, DISTRIBUTION, STATUS AND PROTECTION OF THREE CONGOLESE FRUIT BATS FINAL REPORT Patrick KIPALU Team Leader Observatoire Congolais pour la Protection de l’Environnement OCPE – ong Kinshasa – Democratic Republic of the Congo E-mail: [email protected] APRIL 2009 1 Table of Content Acknowledgements…………………………………………………………………. p3 I. Project Summary……………………………………………………………….. p4 II. Introduction…………………………………………………………………… p4-p7 III. Materials and Methods ……………………………………………………….. p7-p10 IV. Results per Study Site…………………………………………………………. p10-p15 1. Pointe-Noire ………………………………………………………….. p10-p12 2. Mayumbe Forest /Luki Reserve……………………………………….. p12-p13 3. Zongo Forest…………………………………………………………... p14 4. Mbanza-Ngungu ………………………………………………………. P15 V. General Results ………………………………………………………………p15-p16 VI. Discussions……………………………………………………………………p17-18 VII. Conclusion and Recommendations……………………………………….p 18-p19 VIII. Bibliography………………………………………………………………p20-p21 Acknowledgements 2 The OCPE (Observatoire Congolais pour la Protection de l’Environnement) project team would like to start by expressing our gratefulness and saying thank you to the BP Conservation Program, which has funded the execution of this project. The OCPE also thanks the Van Tienhoven Foundation which provided a further financial support. Without these organisations, execution of the project would not have been possible. We would like to thank specially the BPCP “dream team”: Marianne D. Carter, Robyn Dalzen and our regretted Kate Stoke for their time, advices, expertise and care, which helped us to complete this work, Our special gratitude goes to Dr. Wim Bergmans, who was the hero behind the scene from the conception to the execution of the research work. Without his expertise, advices and network it would had been difficult for the project team to produce any result from this project. -

Index of Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Vol. 9. Bats

Index of Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Vol. 9. Bats A agnella, Kerivoula 901 Anchieta’s Bat 814 aquilus, Glischropus 763 Aba Leaf-nosed Bat 247 aladdin, Pipistrellus pipistrellus 771 Anchieta’s Broad-faced Fruit Bat 94 aquilus, Platyrrhinus 567 Aba Roundleaf Bat 247 alascensis, Myotis lucifugus 927 Anchieta’s Pipistrelle 814 Arabian Barbastelle 861 abae, Hipposideros 247 alaschanicus, Hypsugo 810 anchietae, Plerotes 94 Arabian Horseshoe Bat 296 abae, Rhinolophus fumigatus 290 Alashanian Pipistrelle 810 ancricola, Myotis 957 Arabian Mouse-tailed Bat 164, 170, 176 abbotti, Myotis hasseltii 970 alba, Ectophylla 466, 480, 569 Andaman Horseshoe Bat 314 Arabian Pipistrelle 810 abditum, Megaderma spasma 191 albatus, Myopterus daubentonii 663 Andaman Intermediate Horseshoe Arabian Trident Bat 229 Abo Bat 725, 832 Alberico’s Broad-nosed Bat 565 Bat 321 Arabian Trident Leaf-nosed Bat 229 Abo Butterfly Bat 725, 832 albericoi, Platyrrhinus 565 andamanensis, Rhinolophus 321 arabica, Asellia 229 abramus, Pipistrellus 777 albescens, Myotis 940 Andean Fruit Bat 547 arabicus, Hypsugo 810 abrasus, Cynomops 604, 640 albicollis, Megaerops 64 Andersen’s Bare-backed Fruit Bat 109 arabicus, Rousettus aegyptiacus 87 Abruzzi’s Wrinkle-lipped Bat 645 albipinnis, Taphozous longimanus 353 Andersen’s Flying Fox 158 arabium, Rhinopoma cystops 176 Abyssinian Horseshoe Bat 290 albiventer, Nyctimene 36, 118 Andersen’s Fruit-eating Bat 578 Arafura Large-footed Bat 969 Acerodon albiventris, Noctilio 405, 411 Andersen’s Leaf-nosed Bat 254 Arata Yellow-shouldered Bat 543 Sulawesi 134 albofuscus, Scotoecus 762 Andersen’s Little Fruit-eating Bat 578 Arata-Thomas Yellow-shouldered Talaud 134 alboguttata, Glauconycteris 833 Andersen’s Naked-backed Fruit Bat 109 Bat 543 Acerodon 134 albus, Diclidurus 339, 367 Andersen’s Roundleaf Bat 254 aratathomasi, Sturnira 543 Acerodon mackloti (see A. -

Updates to the Zoonotic Niche Map of Ebola Virus Disease in Africa

RESEARCH ADVANCE Updates to the zoonotic niche map of Ebola virus disease in Africa David M Pigott1,2*, Anoushka I Millear1, Lucas Earl1, Chloe Morozoff1*, Barbara A Han3, Freya M Shearer2, Daniel J Weiss4,5, Oliver J Brady2, Moritz UG Kraemer4,5, Catherine L Moyes2, Samir Bhatt4,5, Peter W Gething4,5, Nick Golding2,6, Simon I Hay1,2 1Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, University of Washington, Seattle, United States; 2Oxford Big Data Institute, Li Ka Shing Centre for Health Information and Discovery, Oxford, United Kingdom; 3Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies, New York, United States; 4Spatial Ecology and Epidemiology Group, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom; 5Department of Zoology, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom; 6Department of BioSciences, University of Melbourne, Parkville, Australia Abstract As the outbreak of Ebola virus disease (EVD) in West Africa is now contained, attention is turning from control to future outbreak prediction and prevention. Building on a previously published zoonotic niche map (Pigott et al., 2014), this study incorporates new human and animal occurrence data and expands upon the way in which potential bat EVD reservoir species are incorporated. This update demonstrates the potential for incorporating and updating data used to generate the predicted suitability map. A new data portal for sharing such maps is discussed. This output represents the most up-to-date estimate of the extent of EVD zoonotic risk in Africa. These maps can assist in strengthening surveillance and response capacity to contain viral haemorrhagic fevers. DOI: 10.7554/eLife.16412.001 *For correspondence: pigottdm@ uw.edu (DMP); [email protected] (CM) Competing interest: See page 10 Introduction Since the index case in 2013, the West African Ebola epidemic has killed more than 11,000 people Funding: See page 10 (World Heath Organization, 2016) and exposed national and international inadequacies in pan- Received: 30 March 2016 demic preparedness and response (Moon et al., 2015).