Volume 41, 2000

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Diversity and Abundance of Roadkilled Bats in the Brazilian Atlantic Forest

diversity Article Diversity and Abundance of Roadkilled Bats in the Brazilian Atlantic Forest Lucas Damásio 1,2 , Laís Amorim Ferreira 3, Vinícius Teixeira Pimenta 3, Greiciane Gaburro Paneto 4, Alexandre Rosa dos Santos 5, Albert David Ditchfield 3,6, Helena Godoy Bergallo 7 and Aureo Banhos 1,3,* 1 Centro de Ciências Exatas, Naturais e da Saúde, Departamento de Biologia, Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo, Alto Universitário, s/nº, Guararema, Alegre 29500-000, ES, Brazil; [email protected] 2 Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ecologia, Instituto de Ciências Biológicas, Campus Darcy Ribeiro, Universidade de Brasília, Brasília 70910-900, DF, Brazil 3 Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciências Biológicas (Biologia Animal), Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo, Av. Fernando Ferrari, 514, Prédio Bárbara Weinberg, Vitória 29075-910, ES, Brazil; [email protected] (L.A.F.); [email protected] (V.T.P.); [email protected] (A.D.D.) 4 Centro de Ciências Exatas, Naturais e da Saúde, Departamento de Farmácia e Nutrição, Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo, Alto Universitário, s/nº, Guararema, Alegre 29500-000, ES, Brazil; [email protected] 5 Centro de Ciências Agrárias e Engenharias, Departamento de Engenharia Rural, Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo, Alto Universitário, s/nº, Guararema, Alegre 29500-000, ES, Brazil; [email protected] 6 Centro de Ciências Humanas e Naturais, Departamento de Ciências Biológicas, Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo, Av. Fernando Ferrari, 514, Vitória 29075-910, ES, Brazil 7 Departamento de Ecologia, Instituto de Biologia Roberto Alcântara Gomes, Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, Rua São Francisco Xavier 524, Maracanã, Rio de Janeiro 20550-900, RJ, Brazil; [email protected] Citation: Damásio, L.; Ferreira, L.A.; * Correspondence: [email protected] Pimenta, V.T.; Paneto, G.G.; dos Santos, A.R.; Ditchfield, A.D.; Abstract: Faunal mortality from roadkill has a negative impact on global biodiversity, and bats are Bergallo, H.G.; Banhos, A. -

BONNER ZOOLOGISCHE MONOGRAPHIEN, Nr

© Biodiversity Heritage Library, http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/; www.zoologicalbulletin.de; www.biologiezentrum.at NEW WORLD NECTAR-FEEDING BATS: BIOLOGY, MORPHOLOGY AND CRANIOMETRIC APPROACH TO SYSTEMATICS by ERNST-HERMANN SOLMSEN BONNER ZOOLOGISCHE MONOGRAPHIEN, Nr. 44 1998 Herausgeber: ZOOLOGISCHES FORSCHUNGSINSTITUT UND MUSEUM ALEXANDER KOENIG BONN © Biodiversity Heritage Library, http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/; www.zoologicalbulletin.de; www.biologiezentrum.at BONNER ZOOLOGISCHE MONOGRAPHIEN Die Serie wird vom Zoologischen Forschungsinstitut und Museum Alexander Koenig herausgegeben und bringt Originalarbeiten, die für eine Unterbringung in den „Bonner zoologischen Beiträgen" zu lang sind und eine Veröffentlichung als Monographie rechtfertigen. Anfragen bezüglich der Vorlage von Manuskripten sind an die Schriftleitung zu richten; Bestellungen und Tauschangebote bitte an die Bibliothek des Instituts. This series of monographs, published by the Zoological Research Institute and Museum Alexander Koenig, has been established for original contributions too long for inclu- sion in „Bonner zoologische Beiträge". Correspondence concerning manuscripts for pubhcation should be addressed to the editor. Purchase orders and requests for exchange please address to the library of the institute. LTnstitut de Recherches Zoologiques et Museum Alexander Koenig a etabh cette serie de monographies pour pouvoir publier des travaux zoologiques trop longs pour etre inclus dans les „Bonner zoologische Beiträge". Toute correspondance concernante -

Chromosomal Evolution and Phylogeny in the Nullicauda Group

Gomes et al. BMC Evolutionary Biology (2018) 18:62 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12862-018-1176-3 RESEARCHARTICLE Open Access Chromosomal evolution and phylogeny in the Nullicauda group (Chiroptera, Phyllostomidae): evidence from multidirectional chromosome painting Anderson José Baia Gomes1,3, Cleusa Yoshiko Nagamachi1,4, Luis Reginaldo Ribeiro Rodrigues2, Malcolm Andrew Ferguson-Smith5, Fengtang Yang6, Patricia Caroline Mary O’Brien5 and Julio Cesar Pieczarka1,4* Abstract Background: The family Phyllostomidae (Chiroptera) shows wide morphological, molecular and cytogenetic variation; many disagreements regarding its phylogeny and taxonomy remains to be resolved. In this study, we use chromosome painting with whole chromosome probes from the Phyllostomidae Phyllostomus hastatus and Carollia brevicauda to determine the rearrangements among several genera of the Nullicauda group (subfamilies Gliphonycterinae, Carolliinae, Rhinophyllinae and Stenodermatinae). Results: These data, when compared with previously published chromosome homology maps, allow the construction of a phylogeny comparable to those previously obtained by morphological and molecular analysis. Our phylogeny is largely in agreement with that proposed with molecular data, both on relationships between the subfamilies and among genera; it confirms, for instance, that Carollia and Rhinophylla, previously considered as part of the same subfamily are, in fact, distant genera. Conclusions: The occurrence of the karyotype considered ancestral for this family in several different branches -

(Orchidaceae: Pleurothallidinae) from Península De Osa, Puntarenas, Costa Rica

A NEW LEPANTHES (ORCHIDACEAE: PLEUROTHALLIDINAE) FROM PENÍNSULA DE OSA, PUNTARENAS, COSTA RICA ISLER F. CHINCHILLA,1–3 REINALDO AGUILAR,4 AND DIEGO BOGARÍN1,5,6 Abstract. Lepanthes is one of the most species-rich genera of orchids in the Neotropics, with most of the species found in medium to high elevation forests and few species in lowlands. We describe and illustrate Lepanthes osaensis, a new species from the very wet lowland forest of Península de Osa, Costa Rica. It is similar to Lepanthes cuspidata but differs mostly in the vinous leaves; smaller sepals; the narrower, bilobed petals; and the smaller lip with triangular blades. Notes on its distribution, habitat, flowering, and conservation status, as well as discussion of a taxon with similar morphology, are provided. Keywords: Lepanthes cuspidata, orchid endemism, Pleurothallidinae taxonomy, twig epiphytes, very wet lowland forest Lepanthes Sw. is one of the most species-rich genera of Jiménez and Grayum, 2002; Bogarín and Pupulin, 2007; Pleurothallidinae (Orchidaceae), with over 1200 species Rakosy et al., 2013) and the continued long-term fieldwork from southern Mexico and the Antilles to Bolivia and by the second author (RA). A possible explanation is the northern Brazil (Pridgeon, 2005; Luer and Thoerle, 2012; marked seasonality between dry and wet seasons from Vieira-Uribe and Moreno, 2019; Bogarín et al., 2020). the north toward the central Pacific, contrasting with Lepanthes comprises plants with ramicauls enclosed by the prevailing wet conditions in the Caribbean throughout several infundibular sheaths, named “lepanthiform sheaths,” the year (Kohlmann et al., 2002). The most suitable areas racemose inflorescences of successive flowers, subsimilar, for lowland Lepanthes in the Pacific are the tropical wet glabrous sepals, petals wider than long, frequently bilobed forests from Carara in the central Pacific to Península with divergent lobes, the lip usually trilobed with the lateral de Osa and Burica. -

Quaternary Murid Rodents of Timor Part I: New Material of Coryphomys Buehleri Schaub, 1937, and Description of a Second Species of the Genus

QUATERNARY MURID RODENTS OF TIMOR PART I: NEW MATERIAL OF CORYPHOMYS BUEHLERI SCHAUB, 1937, AND DESCRIPTION OF A SECOND SPECIES OF THE GENUS K. P. APLIN Australian National Wildlife Collection, CSIRO Division of Sustainable Ecosystems, Canberra and Division of Vertebrate Zoology (Mammalogy) American Museum of Natural History ([email protected]) K. M. HELGEN Department of Vertebrate Zoology National Museum of Natural History Smithsonian Institution, Washington and Division of Vertebrate Zoology (Mammalogy) American Museum of Natural History ([email protected]) BULLETIN OF THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY Number 341, 80 pp., 21 figures, 4 tables Issued July 21, 2010 Copyright E American Museum of Natural History 2010 ISSN 0003-0090 CONTENTS Abstract.......................................................... 3 Introduction . ...................................................... 3 The environmental context ........................................... 5 Materialsandmethods.............................................. 7 Systematics....................................................... 11 Coryphomys Schaub, 1937 ........................................... 11 Coryphomys buehleri Schaub, 1937 . ................................... 12 Extended description of Coryphomys buehleri............................ 12 Coryphomys musseri, sp.nov.......................................... 25 Description.................................................... 26 Coryphomys, sp.indet.............................................. 34 Discussion . .................................................... -

Butterflies of the Golfo Dulce Region Costa Rica

Butterflies of the Golfo Dulce Region Costa Rica Corcovado National Park Piedras Blancas National Park ‚Regenwald der Österreicher‘ Authors Lisa Maurer Veronika Pemmer Harald Krenn Martin Wiemers Department of Evolutionary Biology Department of Animal Biodiversity University of Vienna University of Vienna Althanstraße 14, 1090 Vienna, Austria Rennweg 14, 1030, Vienna, Austria [email protected] [email protected] Roland Albert Werner Huber Anton Weissenhofer Department of Chemical Ecology Department of Structural and Department of Structural and and Ecosystem Research Functional Botany Functional Botany University of Vienna University of Vienna University of Vienna Rennweg 14, 1030, Vienna, Austria Rennweg 14, 1030, Vienna, Austria Rennweg 14, 1030, Vienna, Austria [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Contents The ‘Tropical Research Station La Gamba’ 4 The rainforests of the Golfo Dulce region 6 Butterflies of the Golfo Dulce Region, Costa Rica 8 Papilionidae - Swallowtail Butterflies 13 Pieridae - Sulphures and Whites 17 Nymphalidae - Brush Footed Butterflies 21 Subfamily Danainae 22 Subfamily Ithomiinae 24 Subfamily Charaxinae 26 Subfamily Satyrinae 27 Subfamily Cyrestinae 33 Subfamily Biblidinae 34 Subfamily Nymphalinae 35 Subfamily Apaturinae 39 Subfamily Heliconiinae 40 Riodinidae - Metalmarks 47 Lycaenidae - Blues 53 Hesperiidae - Skippers 57 Appendix- Checklist of species 61 Acknowledgements 74 References 74 Picture credits 75 Index 78 3 The ‘Tropical Research Station La Gamba’ Roland Albert Secretary General of the ‘Society for the Preservation of the Tropical Research Station La Gamba’ Department of Chemical Ecology and Ecosystem Research, University of Vienna The main building of the Tropical Research Station In 1991, Michael Schnitzler, a distinguished also provided ideal conditions for promoting musician and former professor at the Univer- Austrian research and teaching programmes in sity of Music and Performing Arts in Vienna, rainforests. -

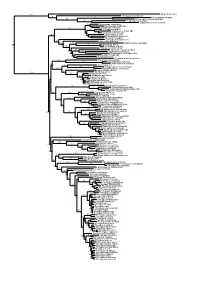

Figs1 ML Tree.Pdf

100 Megaderma lyra Rhinopoma hardwickei 71 100 Rhinolophus creaghi 100 Rhinolophus ferrumequinum 100 Hipposideros armiger Hipposideros commersoni 99 Megaerops ecaudatus 85 Megaerops niphanae 100 Megaerops kusnotoi 100 Cynopterus sphinx 98 Cynopterus horsfieldii 69 Cynopterus brachyotis 94 50 Ptenochirus minor 86 Ptenochirus wetmorei Ptenochirus jagori Dyacopterus spadiceus 99 Sphaerias blanfordi 99 97 Balionycteris maculata 100 Aethalops alecto 99 Aethalops aequalis Thoopterus nigrescens 97 Alionycteris paucidentata 33 99 Haplonycteris fischeri 29 Otopteropus cartilagonodus Latidens salimalii 43 88 Penthetor lucasi Chironax melanocephalus 90 Syconycteris australis 100 Macroglossus minimus 34 Macroglossus sobrinus 92 Boneia bidens 100 Harpyionycteris whiteheadi 69 Harpyionycteris celebensis Aproteles bulmerae 51 Dobsonia minor 100 100 80 Dobsonia inermis Dobsonia praedatrix 99 96 14 Dobsonia viridis Dobsonia peronii 47 Dobsonia pannietensis 56 Dobsonia moluccensis 29 Dobsonia anderseni 100 Scotonycteris zenkeri 100 Casinycteris ophiodon 87 Casinycteris campomaanensis Casinycteris argynnis 99 100 Eonycteris spelaea 100 Eonycteris major Eonycteris robusta 100 100 Rousettus amplexicaudatus 94 Rousettus spinalatus 99 Rousettus leschenaultii 100 Rousettus aegyptiacus 77 Rousettus madagascariensis 87 Rousettus obliviosus Stenonycteris lanosus 100 Megaloglossus woermanni 100 91 Megaloglossus azagnyi 22 Myonycteris angolensis 100 87 Myonycteris torquata 61 Myonycteris brachycephala 33 41 Myonycteris leptodon Myonycteris relicta 68 Plerotes anchietae -

RECORDS CODIFICATION MANUAL Prepared by the Office Of

RECORDS CODIFICATION MANUAL Prepared by The Office of Communications and Records Department of State (Adopted January 1, 1950—Revised January 1, 1955) I I CLASSES OF RECORDS Glass 0 Miscellaneous. I Class 1 Administration of the United States Government. Class 2 Protection of Interests (Persons and Property). I Class 3 International Conferences, Congresses, Meetings and Organizations. United Nations. Organization of American States. Multilateral Treaties. I Class 4 International Trade and Commerce. Trade Relations, Treaties, Agreements. Customs Administration. Class 5 International Informational and Educational Relations. Cultural I Affairs and Programs. Class 6 International Political Relations. Other International Relations. I Class 7 Internal Political and National Defense Affairs. Class 8 Internal Economic, Industrial and Social Affairs. 1 Class 9 Other Internal Affairs. Communications, Transportation, Science. - 0 - I Note: - Classes 0 thru 2 - Miscellaneous; Administrative. Classes 3 thru 6 - International relations; relations of one country with another, or of a group of countries with I other countries. Classes 7 thru 9 - Internal affairs; domestic problems, conditions, etc., and only rarely concerns more than one I country or area. ' \ \T^^E^ CLASS 0 MISCELLANEOUS 000 GENERAL. Unclassifiable correspondence. Crsnk letters. Begging letters. Popular comment. Public opinion polls. Matters not pertaining to business of the Department. Requests for interviews with officials of the Department. (Classify subjectively when possible). Requests for names and/or addresses of Foreign Service Officers and personnel. Requests for copies of treaties and other publications. (This number should never be used for communications from important persons, organizations, etc.). 006 Precedent Index. 010 Matters transmitted through facilities of the Department, .1 Telegrams, letters, documents. -

7 Meeting of the Parties

Inf.EUROBATS.MoP7.45 7th Meeting of the Parties Brussels, Belgium, 15 – 17 September 2014 Report on Autecological Studies for Priority Species Convenor: Stéphane Aulagnier In accordance with Resolution 4.12, the current work being carried out on autecological studies of the Priority List of species (Rhinolophus euryale, Myotis capaccinii and Miniopterus schreibersii) should be updated by the Advisory Committee and should be made public. References of papers and reports dealing with autecological studies Rhinolophus euryale Barataud M., Jemin J., Grugier Y. & Mazaud S., 2009. Étude sur les territoires de chasse du Rhinolophe euryale, Rhinolophus euryale, en Corrèze, site Natura 2000 des Abîmes de la Fage. Le Naturaliste. Vendéen, 9 : 43-55. The cave of la Fage (Noailles, Département of Corrèze) is a major site for the Mediterranean horseshoe bat, Rhinolophus euryale Blasius 1853. However, contrary to the tendency to increase noted over the last 20 years in various other birth sites in France, numbers at la Fage have shown no change. One of the suspected causes links this to the presence of the A20 motorway, less than a kilometre away, where corpses have been collected. This article presents the results of a radio-tracking study of the space occupied by the colony, during the summers of 2006 and 2007. Voigt C.C., Schuller B.M., Greif S. & Siemers B.M., 2010. Perch-hunting in insectivorous Rhinolophus bats is related to the high energy costs of manoeuvring in flight. Journal of Comparative Physiology Biochemical Systemic and Environmental Physiology, 180(7): 1079-1088 Foraging behaviour of bats is supposedly largely influenced by the high costs of flapping flight. -

EU Action Plan for the Conservation of All Bat Species in the European Union

Action Plan for the Conservation of All Bat Species in the European Union 2018 – 2024 October 2018 Action Plan for the Conservation of All Bat Species in the European Union 2018 - 2024 EDITORS: BAROVA Sylvia (European Commission) & STREIT Andreas (UNEP/EUROBATS) COMPILERS: MARCHAIS Guillaume & THAURONT Marc (Ecosphère, France/The N2K Group) CONTRIBUTORS (in alphabetical order): BOYAN Petrov * (Bat Research & Conservation Centre, Bulgaria) DEKKER Jasja (Animal ecologist, Netherlands) ECOSPHERE: JUNG Lise, LOUTFI Emilie, NUNINGER Lise & ROUÉ Sébastien GAZARYAN Suren (EUROBATS) HAMIDOVIĆ Daniela (State Institute for Nature Protection, Croatia) JUSTE Javier (Spanish association for the study and conservation of bats, Spain) KADLEČÍK Ján (Štátna ochrana prírody Slovenskej republiky, Slovakia) KYHERÖINEN Eeva-Maria (Finnish Museum of Natural History, Finland) HANMER Julia (Bat Conservation Trust, United Kingdom) LEIVITS Meelis (Environmental Agency of the Ministry of Environment, Estonia) MARNELl Ferdia (National Parks & Wildlife Service, Ireland) PETERMANN Ruth (Federal Agency for Nature Conservation, Germany) PETERSONS Gunărs (Latvia University of Agriculture, Latvia) PRESETNIK Primož (Centre for Cartography of Fauna and Flora, Slovenia) RAINHO Ana (Institute for the Nature and Forest Conservation, Portugal) REITER Guido (Foundation for the protection of our bats in Switzerland) RODRIGUES Luisa (Institute for the Nature and Forest Conservation, Portugal) RUSSO Danilo (University of Napoli Frederico II, Italy) SCHEMBRI -

ARTHROPODA Subphylum Hexapoda Protura, Springtails, Diplura, and Insects

NINE Phylum ARTHROPODA SUBPHYLUM HEXAPODA Protura, springtails, Diplura, and insects ROD P. MACFARLANE, PETER A. MADDISON, IAN G. ANDREW, JOCELYN A. BERRY, PETER M. JOHNS, ROBERT J. B. HOARE, MARIE-CLAUDE LARIVIÈRE, PENELOPE GREENSLADE, ROSA C. HENDERSON, COURTenaY N. SMITHERS, RicarDO L. PALMA, JOHN B. WARD, ROBERT L. C. PILGRIM, DaVID R. TOWNS, IAN McLELLAN, DAVID A. J. TEULON, TERRY R. HITCHINGS, VICTOR F. EASTOP, NICHOLAS A. MARTIN, MURRAY J. FLETCHER, MARLON A. W. STUFKENS, PAMELA J. DALE, Daniel BURCKHARDT, THOMAS R. BUCKLEY, STEVEN A. TREWICK defining feature of the Hexapoda, as the name suggests, is six legs. Also, the body comprises a head, thorax, and abdomen. The number A of abdominal segments varies, however; there are only six in the Collembola (springtails), 9–12 in the Protura, and 10 in the Diplura, whereas in all other hexapods there are strictly 11. Insects are now regarded as comprising only those hexapods with 11 abdominal segments. Whereas crustaceans are the dominant group of arthropods in the sea, hexapods prevail on land, in numbers and biomass. Altogether, the Hexapoda constitutes the most diverse group of animals – the estimated number of described species worldwide is just over 900,000, with the beetles (order Coleoptera) comprising more than a third of these. Today, the Hexapoda is considered to contain four classes – the Insecta, and the Protura, Collembola, and Diplura. The latter three classes were formerly allied with the insect orders Archaeognatha (jumping bristletails) and Thysanura (silverfish) as the insect subclass Apterygota (‘wingless’). The Apterygota is now regarded as an artificial assemblage (Bitsch & Bitsch 2000). -

Diversity of Bat Species Across Dominica

Diversity of Bat Species across Dominica Brittany Moore, Hannah Rice, Meredith Stroud Texas A&M University Tropical Field Biology Dominica 2015 Dr. Thomas Lacher Dr. Jim Woolley Abstract: Twelve species of bats can be found on the island of Dominica, however there are still some species that have not been thoroughly catalogued. Our report is based on further findings regarding Artibeus jamaicensis, Sturnira lilium, Ardops nichollsi, Myotis dominicensis, Monophyllus plethodon and Brachyphylla cavernarum. We collected mass, forearm length, hind foot length, ear length, sex, and reproductive condition for every individual bat and then compared this information among species to observe morphological differences. We also added new data to past studies on wing loading and aspect ratios for the species we caught. We found a statistical significance among species in body size measure and wing morphology. Among the bats examined, the measurements can be used in order to positively identify species. Introduction: Dominica, also known as the Nature Island, is home to a great diversity of plants and animals. There are many various habitats ranging from dry forest to montane and elfin rainforest. Within each habitat, one may find species only endemic to that area. Animal activity at night in Dominica is quite different than what can be witnessed during the day. As nighttime falls, the call of the tink frog can be heard all over the island, and the mating click beetles will illuminate even the darkest of forests, but by far the most exciting nocturnal animals are the thousands of bats that come alive when the sun begins to set.