Knut Døscher Master.Pdf (1.728Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dagene I Nürnberg Og OL-Stadion I Berlin

[36] SØNDAG 3. MARS2013 [PÅ SØNDAG] MASSEMORDERNE PÅ EKEBERG: Reinhard Heydrich – sjef for det tysk politi og sikkerhetstjeneste – på inspeksjon av æreskirkegården på Ekeberg den 4. septem- ber 1941. På bildet er han flankert av gestaposjefen Heinrich Müller og den norske gestaposjefen Heinrich Fehlis. Foto: Norges Hjemmefrontmuseum Tegningene etterlot ingen tvil om at her skulle det gjenskapes en atmosfære av parti- dagene i Nürnberg og OL-Stadion i Berlin. r kistene legges i to lag ovenpå hverandre selsdag og årsdagen for angrepet på Nor- Heydrich mante til mer brutalitet og på grunn av plassmangel. Og, det fort- ge, var blant de faste begivenhetene som håndfast omgang med nordmennene. satte å strømme inn med drepte Hitler- ble markert stort på Ekeberg. Under sli- FAKTA Knapt 3000 tyskere nådde å bli begra- soldater. ke seremonier ble det gjerne også fore- vet på Ekeberg før krigen var slutt i mai Etter at de hengende hagene var an- tatt høytidelige medaljeoverrekkelser, ÆRESKIRKEGÅRDEN 1945. I fredsdagene ble det ene trappe- lagt, og trappene bygd oppover i land- forteller Berit Nøkleby. h Æreskirkegården ble tatt i bruk løpet forsøkt sprengt. De nazistiske skapet, kjørte lastebiler fra Wehrmacht i monumentene ble fjernet, men ellers TREKORS MED MØNER av tyskerne i juni 1940. De første skytteltrafikk fra kirkegårder i Oslo og åra etter 1945, ble den holdt i gikk livet – og døden – sin vante gang. omegn. Virksomheten foregikk i ly av SS-sjefen Heinrich Himmler dro også orden av tyske krigsfanger. UT AV BYEN nattemørket – nordmennene skulle ikke sporenstreks til den tyske «Ehrenfried- h Høsten 1952 ble den besluttet få gleden av å se kistene med hundrevis hof» under et langt besøk i Norge i febru- fjernet. -

Kopstukken Van De Nsb

KOPSTUKKEN VAN DE NSB Marcel Bergen & Irma Clement Marcel Bergen & Irma Clement KOPSTUKKEN VAN DE NSB UITGEVERIJ MOKUMBOOKS Inhoud Inleiding 4 Nationaalsocialisme en fascisme in Nederland 6 De NSB 11 Anton Mussert 15 Kees van Geelkerken 64 Meinoud Rost van Tonningen 98 Henk Feldmeijer 116 Max Blokzijl 132 Robert van Genechten 155 Johan Carp 175 Arie Zondervan 184 Tobie Goedewaagen 198 Henk Woudenberg 210 Evert Roskam 222 Noten 234 Literatuur 236 Colofon 238 dwang te overtuigen van de Groot-Germaanse gedachte. Het gevolg is dat Mussert zich met enkele getrouwen terug- trekt op het hoofdkwartier aan de Maliebaan in Utrecht en de toenemende druk probeert te pareren met notities, toespraken en concessies. Naarmate de bezetting voortduurt nemen de concessies die Mussert aan de Duitse bezetter doet toe. Inleiding De Nationaal Socialistische Beweging (NSB) speelt tijdens Het Rijkscommissariaat de Tweede Wereldoorlog een opmerkelijke rol. Op 14 mei 1940 aanvaardt Arthur Seyss-Inquart in de De NSB, die op 14 december 1931 in Utrecht is opgericht in Ridderzaal de functie van Rijkscommissaris voor de een zaaltje van de Christelijke Jongenmannen Vereeniging, bezette Nederlandse gebieden. Het Rijkscommissariaat vecht tijdens haar bestaan een richtingenstrijd uit. Een strijd is een civiel bestuursorgaan en bestaat verder uit: die gaat tussen de Groot-Nederlandse gedachte, die streeft – Friederich Wimmer (commissaris-generaal voor be- naar een onafhankelijk Groot Nederland binnen een Duits stuur en justitie en plaatsvervanger van Seyss-Inquart). Rijk en de Groot-Germaanse gedachte,waarin Nederland – Hans Fischböck (generaal-commissaris voor Financiën volledig opgaat in een Groot-Germaans Rijk. Niet alleen de en Economische Zaken). richtingenstrijd maakt de NSB politiek vleugellam. -

Diplomarbeit

DIPLOMARBEIT Organisationsstrukturen der deutschen Besatzungsverwaltungen in Frankreich, Belgien und den Niederlanden unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Stellung des SS- und Polizeiapparates vorgelegt von: Jörn Mazur am: 16. Dezember 1997 1. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. W. Seibel 2. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. E. Immergut UNIVERSITÄT KONSTANZ FAKULTÄT FÜR VERWALTUNGSWISSENSCHAFT Inhaltsverzeichnis Abkürzungsverzeichnis I. Einführung ............................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Thematik ................................................................................................. 1 1.2 Ziel ................................................................................................. 2 1.3 Fragestellungen und Thesen ....................................................................... 2 1.3.1 Fragestellungen ..................................................................................... 2 1.3.2 Thesen ..................................................................................... 3 1.4 Methodik ................................................................................................ 4 II. Stellung und Ausweitung des Machtbereichs des SS- und Polizeiapparates im Altreich ................................................................................................ 6 2.1 Stellung und Ausweitung des Machtbereichs des SS- und Polizeiapparates vor 1939 .................................................................................................... -

Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Mensen, macht en mentaliteiten achter prikkeldraad: een historisch- sociologische studie van concentratiekamp Vught (1943-1944) Meeuwenoord, A.M.B. Publication date 2011 Document Version Final published version Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Meeuwenoord, A. M. B. (2011). Mensen, macht en mentaliteiten achter prikkeldraad: een historisch-sociologische studie van concentratiekamp Vught (1943-1944). General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:04 Oct 2021 Mensen, macht en mentaliteiten achter prikkeldraad Een historisch-sociologische studie van concentratiekamp Vught (1943-1944) Marieke Meeuwenoord 1 Mensen, macht en mentaliteiten achter prikkeldraad 2 Mensen, macht en mentaliteiten achter prikkeldraad Een historisch-sociologische studie van concentratiekamp Vught (1943-1944) ACADEMISCH PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Universiteit van Amsterdam op gezag van de Rector Magnificus prof. -

Das Polizeiliche Durchgangslager Westerbork

Anna Hájková 23.3.2004 Das Polizeiliche Durchgangslager Westerbork Die niederländische Regierung errichtete Westerbork1 im Oktober 1939 als „zentrales Flüchtlingslager“ für jüdische Flüchtlinge aus Deutschland. Nach der Okkupation des Landes durch die deutsche Wehrmacht im Mai 1940 und der Einsetzung der Zivilverwaltung in Form eines Reichskommissariats wandelten die neuen Machthaber das Lager im Juli 1942 in ein Durchgangslager um. 78 Prozent der niederländischen Juden, d. h. über 101 000 Menschen, wurden von hier aus in die Vernichtungslager Auschwitz-Birkenau und Sobibór deportiert; von ihnen überlebten nur etwa 5000. Die Niederlande waren sowohl aufgrund von Sprache und Kultur als auch wegen ihrer geografischen Nähe zu Deutschland ein bevorzugtes Ziel jüdischer Flüchtlinge. „Berlin ist nur zehn Stunden mit dem Zug“, erklärten deutsche Juden, die noch jahrelang nach ihrer Emigration zu Besuch zurückkehrten.2 Nach den Novemberpogromen 1938 strömten über 10 000 Juden in die Niederlande, manche von ihnen illegal, d. h. über die „grüne Grenze“. Am 15. Dezember 1938 beschloss die 1 Ich danke René Kruis, Guido Abuys, Mirjam Gutschow, Peter Witte und Elena Demke für ihre Unterstützung beim Verfassen dieses Artikels; auch danke ich der „European Science Foundation Standing Committee for the Humanities–Programme on Occupation in Europe: the impact of National Socialist and Fascist rule“ für ihre finanzielle Unterstützung, die mir den Besuch der niederländischen Archive ermöglichte. 2 Volker Jakob/Annett van der Voort, Anne Frank war nicht allein. Lebensgeschichten deutscher Juden in den Niederlanden, Berlin/Bonn 1995, S. 11. 1 niederländische Regierung aus Angst vor einer „Überflutung“ mit Flüchtlingen, die Grenzen zu schließen und die männlichen Flüchtlinge in Internierungslager wie z. -

1 Introduction

Notes 1 Introduction 1. Donald Macintyre, Narvik (London: Evans, 1959), p. 15. 2. See Olav Riste, The Neutral Ally: Norway’s Relations with Belligerent Powers in the First World War (London: Allen and Unwin, 1965). 3. Reflections of the C-in-C Navy on the Outbreak of War, 3 September 1939, The Fuehrer Conferences on Naval Affairs, 1939–45 (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1990), pp. 37–38. 4. Report of the C-in-C Navy to the Fuehrer, 10 October 1939, in ibid. p. 47. 5. Report of the C-in-C Navy to the Fuehrer, 8 December 1939, Minutes of a Conference with Herr Hauglin and Herr Quisling on 11 December 1939 and Report of the C-in-C Navy, 12 December 1939 in ibid. pp. 63–67. 6. MGFA, Nichols Bohemia, n 172/14, H. W. Schmidt to Admiral Bohemia, 31 January 1955 cited by Francois Kersaudy, Norway, 1940 (London: Arrow, 1990), p. 42. 7. See Andrew Lambert, ‘Seapower 1939–40: Churchill and the Strategic Origins of the Battle of the Atlantic, Journal of Strategic Studies, vol. 17, no. 1 (1994), pp. 86–108. 8. For the importance of Swedish iron ore see Thomas Munch-Petersen, The Strategy of Phoney War (Stockholm: Militärhistoriska Förlaget, 1981). 9. Churchill, The Second World War, I, p. 463. 10. See Richard Wiggan, Hunt the Altmark (London: Hale, 1982). 11. TMI, Tome XV, Déposition de l’amiral Raeder, 17 May 1946 cited by Kersaudy, p. 44. 12. Kersaudy, p. 81. 13. Johannes Andenæs, Olav Riste and Magne Skodvin, Norway and the Second World War (Oslo: Aschehoug, 1966), p. -

Bokliste for Salg Ved Norges Hjemmefrontmuseum Attack At

Bokliste for salg ved Norges Hjemmefrontmuseum Attack at dawn Ron Cope 219,- Bak lås og slå Kristian Ottosen 100,- Bomb Gestapo hovedkvateret Cato Guhnfeldt 250,- Da byen ble stille Henrik Broberg 395,- Da krigen kom hjem til oss Synnøve Veinan Hellerud 350,- De hvite bussene Bo Lidegaard 200,- Det var her det skjedde (pocket) Ottar Samuelsen 119,- Det var her det skjedde (hard cover) Ottar Samuelsen 179,- Englandsfarten (bind 2) Ragnar Ulstein 298,- Englandsfeber Trygve Sørvaag 200,- Etterretningstjenesten i Norge (Amatørenes tid) Ragnar Ulstein 199,- Etterretningstjenesten i Norge (Harde år) Ragnar Ulstein 199,- Etterretningstjenesten i Norge (Nettet strammes) Ragnar Ulstein 199,- Etterretningstjenesten Bind 1, 2, 3 Ragnar Ulstein 500,- Evas dagbøker Eva Liljan Løfsgaard 270,- Fiende eller forbundsfelle Frode Færøy 349,- Flukten fra Holocaust Irene Levin Berman 200,- Forfulgt, fordømt og fortiet Terje Halvorsen 350,- Gestapo mest ettersøkte nordmenn Ingeborg Solbrekke 370,- Rapport fra nr 24 + Bak rapportene Gunnar Sønsteby 270,- Gold run Robert Pearson 200,- Halvdan Koht Åsmund Svendsen 250,- Hils alle og si at jeg lever Hilde Kristoffersen 299,- Hjemmefronten Tore Gjelsvik 200,- Hjemmestyrkene Sverre Kjeldstadli 358,- Hverdag i ruinene Linda Haukland 300,- Hvis vi overlever krigen Bjarnhild Tulloch 250,- Hærføreren Otto Ruge Tom Kristiansen 499,- Ingen nåde Kristian Ottosen 100,- I slik en natt Kristian Ottosen 100,- Jens Chr. Hauge Fullt og helt 250,- Jødar på flukt Ragnar Ulstein 100,- Kampen om sannheten Bjarne Borgersen 100,- -

Abbreviations Used in Notes and Bibliography

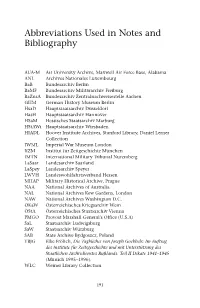

Abbreviations Used in Notes and Bibliography AUA-M Air University Archive, Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama ANL Archives Nationales Luxembourg BaB Bundesarchiv Berlin BaMF Bundesarchiv Militärarchiv Freiburg BaZnsA Bundesarchiv Zentralnachweisestelle Aachen GHM German History Museum Berlin HsaD Hauptstaatsarchiv Düsseldorf HasH Hauptstaatsarchiv Hannover HSaM Hessisches Staatsarchiv Marburg HStAWi Hauptstaatsarchiv Wiesbaden HIADL Hoover Institute Archives, Stanford Library, Daniel Lerner Collection IWML Imperial War Museum London IfZM Institut für Zeitgeschichte München IMTN International Military Tribunal Nuremberg LaSaar Landesarchiv Saarland LaSpey Landesarchiv Speyer LWVH Landeswohlfahrtsverband Hessen MHAP Military Historical Archive, Prague NAA National Archives of Australia NAL National Archives Kew Gardens, London NAW National Archives Washington D.C. OKaW Österreichisches Kriegsarchiv Wein ÖStA Österreichisches Staatsarchiv Vienna PMGO Provost Marshall General’s Office (U.S.A) SaL Staatsarchiv Ludwigsburg SaW Staatsarchiv Würzburg SAB State Archive Bydgoszcz, Poland TBJG Elke Frölich, Die Tagbücher von Joseph Goebbels: Im Auftrag des Institute für Zeitsgeschichte und mit Unterstützung des Staatlichen Archivdienstes Rußlands. Teil II Dikate 1941–1945 (Münich 1995–1996). WLC Weiner Library Collection 191 Notes Introduction: Sippenhaft, Terror and Fear: The Historiography of the Nazi Terror State 1 . Christopher Hutton, Race and the Third Reich: Linguistics, Racial Anthropology and Genetics in the Third Reich (Cambridge 2005), p. 18. 2 . Rosemary O’Kane, Terror, Force and States: The Path from Modernity (Cheltham 1996), p. 19. O’Kane defines a system of terror, as one that is ‘distinguished by summary justice, where the innocence or guilt of the victims is immaterial’. 3 . See Robert Thurston, ‘The Family during the Great Terror 1935–1941’, Soviet Studies , 43, 3 (1991), pp. 553–74. -

Persecution, Collaboration, Resistance

Münsteraner Schriften zur zeitgenössischen Musik 5 Ina Rupprecht (ed.) Persecution, Collaboration, Resistance Music in the ›Reichskommissariat Norwegen‹ (1940–45) Münsteraner Schrift en zur zeitgenössischen Musik Edited by Michael Custodis Volume 5 Ina Rupprecht (ed.) Persecution, Collaboration, Resistance Music in the ‘Reichskommissariat Norwegen’ (1940–45) Waxmann 2020 Münster x New York The publication was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft , the Grieg Research Centre and the Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster as well as the Open Access Publication Fund of the University of Münster. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek Th e Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografi e; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de Münsteraner Schrift en zur zeitgenössischen Musik, Volume 5 Print-ISBN 978-3-8309-4130-9 E-Book-ISBN 978-3-8309-9130-4 DOI: https://doi.org/10.31244/9783830991304 CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 Waxmann Verlag GmbH, 2020 Steinfurter Straße 555, 48159 Münster www.waxmann.com [email protected] Cover design: Pleßmann Design, Ascheberg Cover pictures: © Hjemmefrontarkivet, HA HHI DK DECA_0001_44, saddle of sources regarding the Norwegian resistance; Riksarkivet, Oslo, RA/RAFA-3309/U 39A/ 4/4-7, img 197, Atlantic Presse- bilderdienst 12. February 1942: Th e newly appointed Norwegian NS prime minister Vidkun Quisling (on the right) and Reichskomissar Josef Terboven (on the left ) walking along the front of an honorary -

2018 • Vol. 2 • No. 2

THE JOURNAL OF REGIONAL HISTORY The world of the historian: ‘The 70th anniversary of Boris Petelin’ Online scientific journal 2018 Vol. 2 No. 2 Cherepovets 2018 Publication: 2018 Vol. 2 No. 2 JUNE. Issued four times a year. FOUNDER: Federal State Budgetary Educational Institution of Higher Education ‘Cherepovets State University’ The mass media registration certificate is issued by the Federal Service for Supervi- sion of Communications, Information Technology and Mass Media (Roskomnadzor). Эл №ФС77-70013 dated 31.05.2017 EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: O.Y. Solodyankina, Doctor of Historical Sciences (Cherepovets State University) DEPUTY EDITORS-IN-CHIEF: A.N. Egorov, Doctor of Historical Sciences (Cherepovets State University) E.A. Markov, Doctor of Political Sciences (Cherepovets State University) B.V. Petelin, Doctor of Historical Sciences (Cherepovets State University) A.L. Kuzminykh, Doctor of Historical Sciences (Vologda Institute of Law and Economics, Federal Penitentiary Service of Russia) EDITOR: N.G. MELNIKOVA COMPUTER DESIGN LAYOUT: M.N. AVDYUKHOVA EXECUTIVE EDITOR: N.A. TIKHOMIROVA (8202) 51-72-40 PROOFREADER (ENGLISH): N. KONEVA, PhD, MITI, DPSI, SFHEA (King’s College London, UK) Address of the publisher, editorial office and printing-office: 162600 Russia, Vologda region, Cherepovets, Prospekt Lunacharskogo, 5. OPEN PRICE ISSN 2587-8352 Online media 12 standard published sheets Publication: 15.06.2018 © Federal State Budgetary Educational 1 Format 60 84 /8. Institution of Higher Education Font style Times. ‘Cherepovets State University’, 2018 Contents Strelets М. B.V. Petelin: Scientist, educator and citizen ............................................ 4 RESEARCH Evdokimova Т. Walter Rathenau – a man ahead of time ............................................ 14 Ermakov A. ‘A blood czar of Franconia’: Gauleiter Julius Streicher ...................... -

Viktorgruppa En Studie Av Norske Frontkjemperes Flukt Fra Rettsoppgjøret I 1945

Viktorgruppa En studie av norske frontkjemperes flukt fra rettsoppgjøret i 1945 Erik Øien Masteroppgave HIS4090 60 studiepoeng Institutt for arkeologi, konservering og historie Humanistisk fakultet Universitet i Oslo VÅR 2019 Etter at freden kom til Norge i 1945, ble tusenvis av nordmenn tiltalt for landssvik og satt inn i fengsel og fangeleire. Dette er historien om de første som rømte, om deres svenske medhjelpere og hvordan de organiserte ei fluktrute gjennom Skandinavia med mål om å komme seg til trygghet i Sør-Amerika. Det er også historien om hvordan rømlingenes planer slo feil, hvordan de ble arrestert, og hvordan Viktorgruppa la grunnlaget for en senere fluktvirksomhet som skulle vise seg å være langt mer effektiv. Forord Jeg skylder en stor takk til veileder Terje Emberland for hjelpsomme tilbakemeldinger, nådeløse prioriteringer og svært mye god hjelp til tross for dårlig tid, i tillegg til gode samtaler og spennende historier om norske nazister. Anki Furuseth fortjener også en hjertelig takk for sine bidrag, både gjennom en svært god bok og utlån av litteratur og kildemateriale. Uten henne ville denne oppgaven aldri vært mulig å skrive. Også Tore Pryser, Heléne Lööw og personalet ved Riksarkivet i Oslo skal ha takk for svar på vanskelige spørsmål. Takk til Henriett Røed, Jord Johan Herheim Nylenna og mamma for gjennomlesing og gode innspill. En spesiell takk går til kameratene på skift 2, som har holdt ut med skriving på jobben gjennom alt for mange nattskift. Tusen takk til Kaja, for all hjelp og tålmodighet med rot og bøker overalt, og for at du orker å høre på lange historier om obskure nazister. -

Nieuw Europa Versus Nieuwe Orde De Tweespalt Tussen Mussert En Hitler Over Het Nieuwe Fascistische Europa

Nieuw Europa versus Nieuwe Orde De tweespalt tussen Mussert en Hitler over het nieuwe fascistische Europa Masterscriptie Europese Studies Studiepad Geschiedenis van de Europese Eenheid Faculteit der Geesteswetenschappen Universiteit van Amsterdam Auteur: Ramses Andreas Oomen Studentnummer: 10088849 E-mail: [email protected] Begeleider: dr. M.J.M. Rensen Tweede lezer: dr. R.J. de Bruin Datum van voltooiing: 01-07-2015 2 Inhoudsopgave Inleiding…………………………………………………………………………………... 6 Hoofdstuk 1. Het fascisme als derde weg……………………………………………….. 12 Erfenissen uit het fin de siècle: Europa in crisis………………………………….. 12 Tussen het verouderde liberalisme en het opkomende marxisme………………... 14 ‘Het Germaansche zwaard en de Romeinsche dolk’……………………………... 16 De NSB en het nieuwe Europa………………………………………………….... 18 Mussolini en Hitler als ‘goede Europeanen’?.......................................................... 23 Hoofdstuk 2. De ordening van Europa………………………………………………….. 26 Tussen nationalisme en internationalisme: de zoektocht naar een statenbond…… 26 Ideevorming rondom de Germaanse statenbond…………………………………. 27 Germaanse statenbond tegenover Germaans rijk………………………………… 31 Groot-Nederland en het Dietse ideaal…………………………………………….. 33 Hitler en de ‘volksen’ tegen de Dietse staat……………………………………… 38 Hoofdstuk 3. Europese economische eenheid…………………………………………... 41 Het corporatisme als economische derde weg……………………………………. 41 ‘De deur in het Westen’…………………………………………………………... 44 Nazi-Duitsland en Europese economische samenwerking: discrepantie tussen theorie en praktijk...................................................................................................