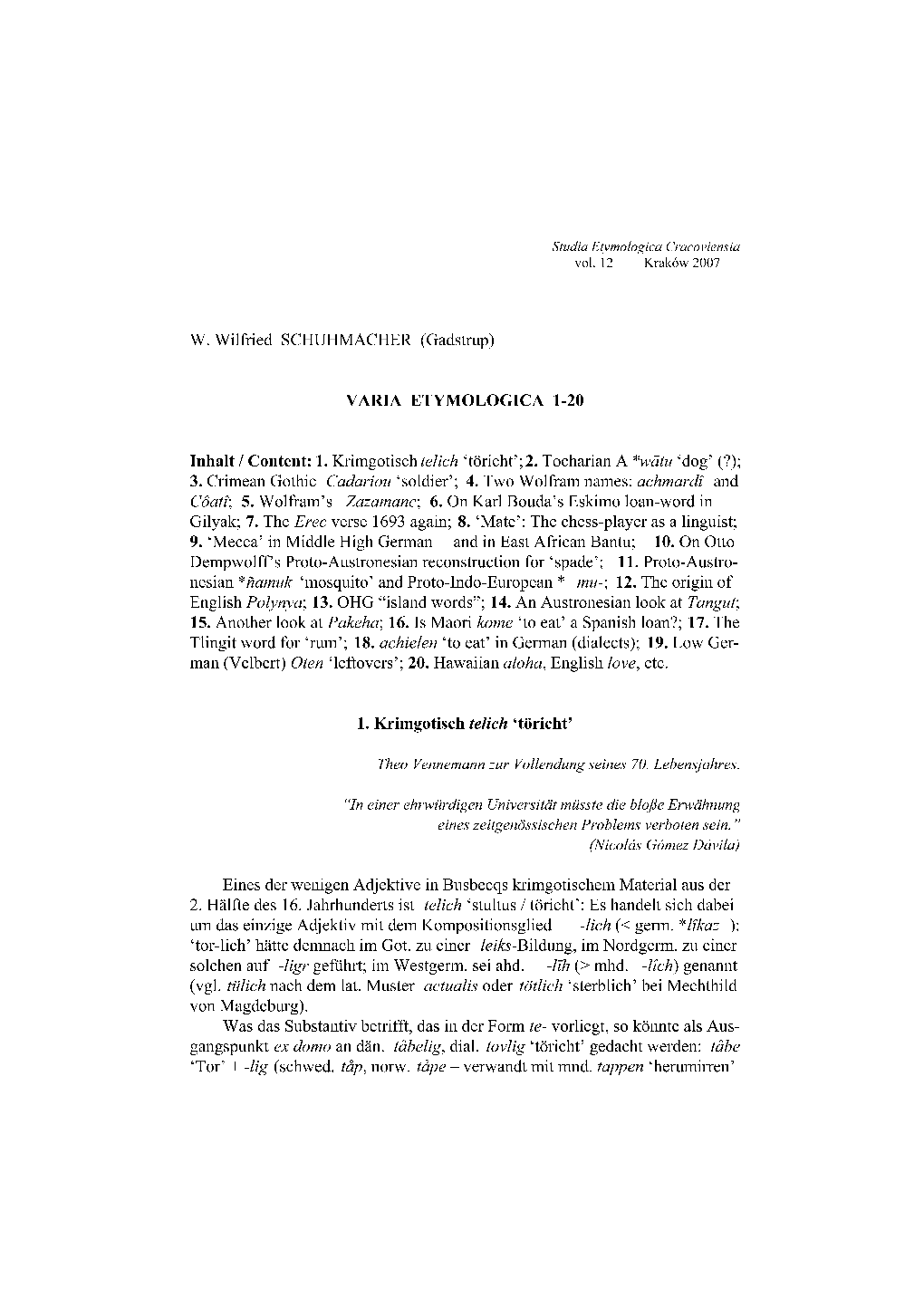

Studia Etymologica Cracoviensia Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Position of Enggano Within Austronesian

7KH3RVLWLRQRI(QJJDQRZLWKLQ$XVWURQHVLDQ 2ZHQ(GZDUGV Oceanic Linguistics, Volume 54, Number 1, June 2015, pp. 54-109 (Article) 3XEOLVKHGE\8QLYHUVLW\RI+DZDL L3UHVV For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/ol/summary/v054/54.1.edwards.html Access provided by Australian National University (24 Jul 2015 10:27 GMT) The Position of Enggano within Austronesian Owen Edwards AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY Questions have been raised about the precise genetic affiliation of the Enggano language of the Barrier Islands, Sumatra. Such questions have been largely based on Enggano’s lexicon, which shows little trace of an Austronesian heritage. In this paper, I examine a wider range of evidence and show that Enggano is clearly an Austronesian language of the Malayo-Polynesian (MP) subgroup. This is achieved through the establishment of regular sound correspondences between Enggano and Proto‒Malayo-Polynesian reconstructions in both the bound morphology and lexicon. I conclude by examining the possible relations of Enggano within MP and show that there is no good evidence of innovations shared between Enggano and any other MP language or subgroup. In the absence of such shared innovations, Enggano should be considered one of several primary branches of MP. 1. INTRODUCTION.1 Enggano is an Austronesian language spoken on the southernmost of the Barrier Islands off the west coast of the island of Sumatra in Indo- nesia; its location is marked by an arrow on map 1. The genetic position of Enggano has remained controversial and unresolved to this day. Two proposals regarding the genetic classification of Enggano have been made: 1. -

Languages of Oceania. Working Papers in Linguistics; Volume 2, Number 3

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 041 275 AL 002 477 AUTHOR Grace, George W. TITLE Languages of Oceania. Working Papers in Linguistics; Volume 2, Number 3. INSTITUTION Hawaii Univ., Honolulu. Dept. of Linguistics. PUB DAVE Apr 70 NOTE 25p.; Paper prepared for the World's Languages Conference, Center for Applied Linguistics, Washington, D.C., April 23-25, 1970 EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF-$0.25 HC-$1.30 DESCRIPTORS *Australian Aboriginal Languages, *Language Classification, *Language Research, Language Typology, *Malayo Polynesian Languages IDENTIFIERS Oceania, *Papuan Languages ABSTRACT One of the first nrotlems concerning research in the languages of Oceania is that the number and location of languages there is not precisely known. Another problem is determining just what a language is. Appell's l!isoglot" may be a better method of distinguishing different languages than "mutual intelligibility." The Oceanic area is "arbitrarily" defined here to include the Australian, Papuan, and Austronesian languages. The number of languages in aboriginal Australia is over 200. All appear to be related, with approximately two-thirds of the continent originally occupied by languages of a single sub-group, Pama-Nyungan. The remaining sub-groups are in the northwestern part of the continent. No language relationships outside Australia have been established. Greenberg has presented a detailed argument for a genetic grouping of the Papuan languages (noted for their great diversity), including the languages of the Andaman Islands, the extinct languages of Tasmania, and at least most of the Papuan languages. The Austronesian family is distributed among a considerable number of different political entities. There is still no general agreement on the earliest branching of Proto-Austronesian. -

Parallel Sound Correspondences in Uab Meto

3DUDOOHO6RXQG&RUUHVSRQGHQFHVLQ8DE0HWR 2ZHQ(GZDUGV 2FHDQLF/LQJXLVWLFV9ROXPH1XPEHU-XQHSS $UWLFOH 3XEOLVKHGE\8QLYHUVLW\RI+DZDL L3UHVV '2,RO )RUDGGLWLRQDOLQIRUPDWLRQDERXWWKLVDUWLFOH KWWSVPXVHMKXHGXDUWLFOH Access provided by Australian National University (7 Sep 2016 03:30 GMT) Parallel Sound Correspondences in Uab Meto Owen Edwards AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY Two parallel sets of sound correspondences are attested in the historical phonology of the Uab Meto (also known as Dawan[ese], Timorese, Atoni) language/dialect cluster. A top-down approach to the data reveals one set of regular sound correspondences in reflexes of Proto-Malayo-Polynesian lexemes, while a bottom-up approach to the data reveals another set of reg- ular correspondences in lexemes for which no Malayo-Polynesian origin has yet been found. I examine each set of sound correspondences in detail and propose a framework for addressing the apparently contradictory data. 1. INTRODUCTION.1 The application of the comparative method is not always straightforward. One frequent problem encountered in applying the comparative method is that of speech strata. When a language has borrowed heavily from a related language, it is often difficult to identify the regular sound correspondences and, as a result, which ele- ment(s) of the lexicon have been borrowed and which are native. This problem was first noted for an Austronesian language by Dempwolff (1922), who identified two strata of vocabulary in Ngaju Dayak, each with different sound corre- spondences. Dyen (1956) showed that these two strata were not evenly distributed among different sections of the lexicon, as one stratum is mostly absent from basic vocabulary. On the basis of this distribution, he identified the stratum absent from basic vocabulary as being borrowings (mainly from Malay), while the stratum found throughout all the lexi- con he identified as being inherited and reflecting the regular sound changes. -

2020 Proceedings

请领导们放心 2020 Proceedings Flying in English -ketun L2 intonation mweo haesseyo HOUSELESSHOMELESS natural language acquisition Subtitles 24th Annual Graduate Student Conference Edited by Victoria Lee College of Languages, Denis Melik Tangiyev Linguistics & Literature Chau Truong 2020 Proceedings Selected papers from the 24th Annual Graduate Student Conference College of Languages, Linguistics & Literature Edited by Victoria Lee Denis Melik Tangiyev Chau Truong Published by 1859 East-West Road #106 Honolulu, HI 96822-2322 nflrc.hawaii.edu cbna 2021 College of Languages, Linguistics & Literature, University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa. Some rights reserved. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons. org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/. Past proceedings in this series are archived in http://scholarspace.manoa.hawaii.edu/handle/10125/9195 The contents of this publication were developed in part under a grant from the U.S. Department of Education (CFDA 84.229, P229A180026). However, the contents do not necessarily represent the policy of the Department of Education, and one should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government. CONTENTS PREFACE ii PLENARY HIGHLIGHTS iii 2020 LLL EXCELLENCE IN RESEARCH AWARD PRESENTATIONS iv HOMELESS OR HOUSELESS: TERMINOLOGY CHANGES FOR HOME OWNER 2 AGENCY Jenniefer Corpuz, Department of English POSITING A HYBRID EXEMPLAR MODEL FOR L2 INTONATION 8 Bonnie J. Fox, Department of East Asian Languages -

Some Evidence Favoring the Central Hypothesis

1 Some Evidence Favoring the Central Hypothesis Isidore Dyen Yale University (Emeritus) The Central hypothesis proposes that the Austronesian homeland was in the neighborhood of New Guinea. It combines the first two alternatives I proposed in 1965 (1965.57), Melanesia-East New Guinea and West New Guinea, as against the third alternative, Taiwan, the locale of the Formosan languages. These hypotheses were reached by lexicostatistics. The third alternative is now called the Formosan hypothesis and is supported by Blust and, we are frequently told, a majority of Austronesianists. 1. The homomeric method and Blust’s charge of circularity My use of the so-called homomeric method has been criticized by Blust (1999.67) as based on circular reasoning. The homomeric method draws inferences leading to subgroups from collections of cognate sets with the same distribution over languages. Such a collection is called a homomery from ‘homo-’ = same, ‘-mer-’ = measure. A homomery is a collection of exclusively shared cognate sets. Blust’s formulation of what he presents as ‘Dyen’s argument’ (ibid.) lacks a citation from my publications because I never published such a statement. The critical part is completely contrived, and is the worse because it can be interpreted as a quotation or paraphrase of an argument that I made concerning the use of homomeries to infer a subgroup. Since he does not cite a source, and I do not recognize it as representing my thinking, it can only be regarded as his own concoction that some may consider unethical. His formulation follows verbatim: ‘...Dyen’s arguments (no citation - ID) for a Formosan subgroup: ‘A = Formosan languages form a subgroup, B = they share some ‘homomeries’, C = they have undergone a period of exclusively shared history. -

Report on the Nasal Language of Bengkulu, Sumatra

DigitalResources Electronic Survey Report 2013-012 ® The Improbable Language: Survey Report on the Nasal Language of Bengkulu, Sumatra Karl Anderbeck Herdian Aprilani The Improbable Language: Survey Report on the Nasal Language of Bengkulu, Sumatra Karl Anderbeck and Herdian Aprilani SIL International® 2013 SIL Electronic Survey Report 2013-012, August 2013 © 2013 Karl Anderbeck, Herdian Aprilani, and SIL International® All rights reserved Abstract/Abstrak In the context of language identification survey activities in Sumatra, Indonesia, two published wordlists of a language variety identified as “Nasal” were unearthed. Other than these wordlists, no documentation of the history, classification or sociolinguistics of this group was extant. In this study, brief fieldwork and resultant analysis are presented on the Nasal language group. The main conclusions are that Nasal is indeed a distinct language with a preliminary classification of isolate within Malayo- Polynesian. In spite of its small speaker population compared to its neighbors, it improbably remains sociolinguistically vital. Dalam konteks survei identifikasi bahasa di Sumatera, Indonesia, digali kembali dua daftar kata yang sudah diterbitkan untuk sebuah ragam wicara yang diidentifikasi sebagai 'Nasal.' Selain kedua daftar kata ini, tidak ada dokumentasi apa pun tentang sejarah, klasifikasi linguistis, atau keadaan sosiolinguistis dari kelompok ini. Dalam kajian ini, disajikan survei lapangan singkat terhadap kelompok bahasa Nasal dan analisis yang dihasilkannya. Kesimpulan utamanya -

In Toba Batak

COMPARATIVE FORMOF ADJECTIVES BY PREFIX UM- IN TOBA BATAK By: Esron Ambarita Lecturer of Faculty of Letters Universitas Methodist Indonesia E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT The objectives of this study are to investigate comparative form of adjectivesby prefix um- in Toba Batak. The results show that comparative form of adjectivesby prefix um- in Toba Batak result invarious morphological and phonological processesas follows: (1) if prefix [um-] is attached to adjectives preceded by vowels, the last phoneme of the prefix is doubled ([um- ]→[umm-]). (2) if the initial phoneme is a bilabial plosive voiced consonant [b], prefix [um-] is pronounced [ub-] as its allomorph. (3) if the initial phoneme is a velarplosive voiced consonant [g], prefix [um-] →[uŋ-]. (4)ifthe initial phoneme is a palato alveolar affricate voiced consonant [j]prefix [um-]→[un-] in spellingbut [uj-] in pronunciation. (5) ifthe initial phoneme is a bilabial nasal voiced consonant [m] prefix [um-] does not change. (6) ifthe initial phoneme is analveolar nasal voiced consonant [n]prefix [um-]→[un-] both in spelling and in pronunciation. (7)ifthe initial phoneme isa bilabial plosive voiceless consonant [p],prefix [um-]→[um-]in spelling but pronounced [up-]. (8) if the initial phoneme is an alveolar rolled voiced consonant [r], prefix[um-]→ [ur-] both in spelling and in pronunciation. (9) ifthe initial phoneme is an alveolar fricative voiceless consonant [s], prefix[um-]→ [un-] in spelling but [us-] in pronunciation. (10)if the initial phoneme is an alveolar plosive voiceless consonant [t], prefix [um-]→ [un-] in spellingbut it is pronounced [ut-]. Keywords: comparative forms, morphological and phonological processes, adjectives 1. -

Comparative Forms of Adjectives by Infix -Um- in Toba Batak By

Comparative Forms of Adjectives by Infix -um- in Toba Batak By: Dr. Esron Ambarita, S.S., M.Hum. Lecturer of Faculty of Letters Universitas Methodist Indonesia E-mail: [email protected] Abstract The objectives of this study are to investigate comparative form of adjectives by infix [-um-] in Toba Batak. The number of adjectives in Toba Batak which can be inserted by infix [-um-] is found in limited number. The results show that in Toba Batak, infix [-um-] can be inserted to base forms of adjectives to form comparative form of which: (1) The initial phoneme of the base forms of the adjectives is an alveolar plosive voiced consonant [d], (2) The initial phoneme of the base forms of the adjectives is a velar plosive voiced consonant [g], (3) The initial phoneme of the base forms of the adjectives is a glottal fricative voiceless consonant [h], (4) The initial phoneme of the base forms of the adjectives is a palato alveolar affricate voiced consonant [j], (5) The initial phoneme of the base forms of the adjectives is an alveolar lateral voiced consonant [l], (6) The initial phoneme of the base forms of the adjectives is an alveolar nasal voiced consonant [n], (7) The initial phoneme of the base forms of the adjectives is an alveolar rolled voiced consonant [r], (8) The initial phoneme of the base forms of the adjectives is an alveolar fricative voiceless consonant [s], (9) The initial phoneme of the base forms of the adjectives is an alveolar plosive voiceless consonant [t]. Keywords: comparative forms, adjectives, infix, morphological processes 1. -

Consonant Geminates in Simalungun Language

Linguistik Indonesia, Agustus 2017, 145-158 Volume ke-35, No. 2 Copyright©2017, Masyarakat Linguistik Indonesia ISSN cetak 0215-4846; ISSN online 2580-24 CONSONANT GEMINATES IN SIMALUNGUN LANGUAGE Luh Anik Mayani* Badan Pengembangan dan Pembinaan Bahasa [email protected] Abstrak Penelitian ini bertujuan untuk mendeskripsikan proses morfofonemik yang dapat menghasilkan geminat dan jenis-jenis geminat dalam bahasa Simalungun. Jenis geminat dibedakan berdasarkan proses morfofonemiknya serta berdasarkan kesejatian geminat, yaitu tipe geminat sejati dan taksejati. Data dalam penelitian ini dikumpulkan melalui penelitian lapangan di Pematang Raya, Kecamatan Raya, Kabupaten Simalungun, Provinsi Sumatra Utara. Berdasarkan analisis dapat disimpulkan bahwa geminat dalam bahasa Simalungun selalu berada di tengah kata. Geminat yang ditemukan adalah [pp], [tt], [kk], [ss], [ll], [gg], [nn], dan [mm]. Berdasarkan proses morfofonemik, geminat dalam bahasa ini dapat dibagi menjadi empat, yaitu geminat yang merupakan hasil dari proses (1) asimilasi nasal mengikuti bunyi hambat homorganik yang ada di belakangnya, (2) velarisasi dan asimilasi, (3) asimilasi bunyi berbeda dalam konsonan rangkap, dan (4) geminat nasal. Berdasarkan kesejatian geminat, Simalungun memiliki geminat sejati dan taksejati. Geminat sejati bersifat leksikal; geminat taksejati dihasilkan melalui proses afiksasi dan klitisasi. Geminat sejati yang ditemukan adalah [pp], [tt], [ss], [kk], [gg] and [mm], sedangkan yang taksejati adalah [ss], [kk], [ll] and [nn]. Kata kunci: geminat konsonan, Simalungun, proses morfofonemik Abstract This study aims to describe morphophonemic processes which result in consonant geminates as well as to classify types of consonant geminates in Simalungun language. Types of geminates in this study are analyzed from the morphophonemic processes resulted in consonant geminates and from the true or fake types of geminates. -

The Subgrouping of Philippine Languages

145 •• JULY, 1966 "All the sciences concerned with hu enterprise. If reflects a sense of conscious man beings that range from the abstrac ness, of awareness, finally, that to seek tions of economics through sociology to and to know the truth is not the final anthropology and psychology are, in part, goal, in society. In science, it is. But in efforts to lower the degree of empiricism society, the final goal is to know what in certain areas; in part they are efforts to do with the truth, once you have it. to organize and systematize empirical pro Thus, the evolution of the social sciences, cedures. "14 arriving on the scene last, can be inter preted as appearing on the scene late not One might therefore view our concern because of its lack of importance but be with experimentation in the social sciences •• as a final step which has evolved in o':!r cause of it. process of intellectualization-a step made The application of the social sciences necessary by our need to know the mys are pervasive throughout the other sciences teries of our own human behavior. that because it attempts to provide us with it has evolved last, that man has turned the nature of the truth about ourselves. his intellectual quests finally to the study. To the extent that scientific truth calls of man and his societies after first dis for choices to be made all along the line, enchanting the non-living world and then the contributions of the social sciences to the living world without man in it sug our self-understanding as human beings gests an optimistic view to the scientific enables us to make better choices and to 14 Conant. -

Foreign Language, Area, and Other International Studies: A

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 195 174 FL 012 093 AUTHOR Petrov, Julia A., Comp.:Brosseau, John P.,Ed. TITLE Foreign Language, Area, and Other International Studies:A Bibliography of Pesearch and Instructional Materials Completed under the National Defense Education Act of 1959, Title VI, S'ction 602. List No. 9. INSTITUTION Center for Applied Linguistics, Washington, D.C. 'SPONS AGENCY Bureau of Postsecondary Education (DREW /OE), Washington, D.C. Div.cf International Education. TEPORT NO F-90-14017 PUB DATE BO -CONTRACT 300-90-009 NOTE 94p. EDRS PRICE MF01/PC04 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Area Studies: Conference Papers: Educational Pesearch: *Instructional Materials: International Studies: *Language Pesearch: Linguistics: *Modern Languages: *Second Language Instruction: Surveys: Teaching Methods: *Uncommonly Taught Languages -71)ENTIFIEPS *National Defense rducation Act Title VI ABSTFACT This bibliography lists publications produced by proiects sponsored by the International Division (nowOffice of International Education) of the U.-S. Office (nowDepartment) of Education, for the period of the last 21years. The approximately 900 citations cover studies and surveys, conferences, linguist:LCstudies, research it language-teaching methods, and specializedmaterials in the commonly and uncommonly taught languages and inforeign area studiet. Each citation includes author, title, authoraffiliation, institutional source where applicable, publication informationwhere applicable, and EPIC ordering cumber where applicable.An index by author, institution, language, -

Positional Neutralization: a Phonologization Approach to Typological Patterns

Positional Neutralization: A Phonologization Approach to Typological Patterns by Jonathan Allen Barnes B.A. (Columbia University) 1992 M.A. (University of California, Berkeley) 1995 M.A. (University of California, Berkeley) 1997 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics in the GRADUATE DIVISION of the UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY Committee in charge: Professor Sharon Inkelas, Chair Professor Andrew Garrett Professor Larry M. Hyman Professor Alan Timberlake Fall 2002 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Positional Neutralization: A Phonologization Approach to Typological Patterns ©2002 by Jonathan Allen Barnes Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Abstract Positional Neutralization: A Phonologization Approach to Typological Patterns by Jonathan Allen Barnes Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics University of California, Berkeley Professor Sharon Inkelas, Chair This study investigates the typology of patterns of positional neutralization, a term referring to systems in which, from a given set of oppositions, one structural position licenses a wider array of contrasts than another. Patterns of positional neutralization of vowel contrasts are surveyed in three pairs of strong and weak positions: stressed/unstressed, final/non-final, and initial/non-initial. For each pair, regularities involving the phonetic content of neutralization patterns are accounted for using a phonologization-based approach to typological patterns. In the phonologization model, phonetics influences phonology only by providing the gradient inputs out of which categorical patterns are created by phonologization. Perceptually ambiguous language-specific phonetic patterns are reinterpreted by listeners, producing new phonological representations of the relevant strings.