Positional Neutralization: a Phonologization Approach to Typological Patterns

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cambridge Handbook of Phonology

This page intentionally left blank The Cambridge Handbook of Phonology Phonology – the study of how the sounds of speech are represented in our minds – is one of the core areas of linguistic theory, and is central to the study of human language. This state-of-the-art handbook brings together the world’s leading experts in phonology to present the most comprehensive and detailed overview of the field to date. Focusing on the most recent research and the most influential theories, the authors discuss each of the central issues in phonological theory, explore a variety of empirical phenomena, and show how phonology interacts with other aspects of language such as syntax, morph- ology, phonetics, and language acquisition. Providing a one-stop guide to every aspect of this important field, The Cambridge Handbook of Phonology will serve as an invaluable source of readings for advanced undergraduate and graduate students, an informative overview for linguists, and a useful starting point for anyone beginning phonological research. PAUL DE LACY is Assistant Professor in the Department of Linguistics, Rutgers University. His publications include Markedness: Reduction and Preservation in Phonology (Cambridge University Press, 2006). The Cambridge Handbook of Phonology Edited by Paul de Lacy CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 8RU, UK Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521848794 © Cambridge University Press 2007 This publication is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provision of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. -

Florida Department of Education Home Language Codes

Florida Department of Education Home Language Codes Code Home Language OM (Afan) Oromo AB Abkhazian AC Abnaki AD Achumawi AA Afar AK Afrikaans AE Ahtena EF Akan EK Akateko AF Alabama AL Albanian, Shqip AG Aleut AH Algonquian WJ American Sign Language AM Amharic AI Apache AR Arabic AJ Arapaho AO Araucanian AP Arikara AN Armenian, Hayeren AS Assamese AQ Athapascan AT Atsina AU Atsugewi AV Aucanian WK Awadhi AW Aymara AZ Azerbaijani AX Aztec BA Bantu BC Bashkir BQ Basque, Euskera BS Bassa BJ Belarusian Code Home Language BE Bengali, Bangla BR Berber BP Bhojpuri DZ Bhutani BH Bihari BI Bislama BG Blackfoot BF Breton BL Bulgarian BU Burmese, Myanmasa BD Byelorussian CB Caddo CC Cahuilla CD Cakchiquel CA Cambodian, Khmer CN Cantonese EC Carolinian CT Catalan CE Cayuga ZA Cebuano ED Chamorro CF Chasta Costa CG Chemeheuvi CI Cherokee CJ Chetemacha CK Cheyenne ZB Chhattisgarhi ZC Chinese, Hakka ZD Chinese, Min Nau (Fukienese or Fujianese) CH Chinese, Zhongwen CL Chinook Jargon CM Chiricahua ZE Chittagonian CP Chiwere CQ Choctaw CS Chumash EE Chuukese/Trukese Code Home Language CU Clallam CV Coast Miwok CW Cocomaricopa CX Coeur D’Alene CY Columbia DF Comanche CO Corsican DG Cowlitz DJ Cree ZF Creole HR Croatian, Hrvatski DK Crow DH Cuna DI Cupeno CZ Czech DB Dakota DA Danish DL Deccan DC Delaware DD Delta River Yuman DE Diegueno DU Dutch, Netherlands DO Dzongkha EN English EA Eskimo EO Esperanto ES Estonian EB Eyak FO Faroese FA Farsi, Persian FJ Fijian FL Filipino FI Finnish, Suomi FB Foothill North Yokuts FC Fox FR French FD French Cree Code Home -

Introducing Phonology

Introducing Phonology Designed for students with only a basic knowledge of linguistics, this leading textbook provides a clear and practical introduction to phonology, the study of sound patterns in language. It teaches in a step-by-step fashion the logical techniques of phonological analysis and the fundamental theories that underpin it. This thoroughly revised and updated edition teaches students how to analyze phonological data, how to think critically about data, how to formulate rules and hypotheses, and how to test them. New to this edition: • Improved examples, over 60 exercises, and 14 new problem sets from a wide variety of languages encourage students to practice their own analysis of phonological processes and patterns • A new and updated reference list of phonetic symbols and an updated transcription system, making data more accessible to students • Additional online material includes pedagogical suggestions and password-protected answer keys for instructors david odden is Professor Emeritus in Linguistics at Ohio State University. Cambridge Introductions to Language and Linguistics This new textbook series provides students and their teachers with accessible introductions to the major subjects encountered within the study of language and linguistics. Assuming no prior knowledge of the subject, each book is written and designed for ease of use in the classroom or seminar, and is ideal for adoption on a modular course as the core recommended textbook. Each book offers the ideal introductory material for each subject, presenting students with an overview of the main topics encountered in their course, and features a glossary of useful terms, chapter previews and summaries, suggestions for further reading, and helpful exercises. -

Prosody – Introductory

THE PHONOLOGY OF RHONDDA VALLEYS ENGLISH. (Rod Walters, University of Glamorgan, 2006) 4. PROSODY – INTRODUCTORY (Readers unfamiliar with the prosodic terms used will find explanations in the Glossary.) 4.1 Aims of RVE Research Prosody (stress, rhythm, intonation etc) contributes strongly towards the ‘melody’ of Welsh English accents. Chapter 5 will attempt to describe the main features of RVE prosody. Like t'Hart, Collier, and Cohen of the Institute for Perception Research in Eindhoven (1990: 2-6), the approach will be primarily ‘from the phonetic level of observation’.35 Comments will be made concerning the functions / meanings of the prosodic forms identified, but the researcher is very aware that the links between meaning and prosody are seldom straightforward: (1) discerning the meaning of an utterance is a matter of pragmatic interpretation in which many factors beside prosody need to be taken into account (propositional content of the lexis-grammar, full context of the situation, speakers’ body language etc) (2) several prosodic features, e.g. voice quality, loudness and intonation, may be operative at the same time and therefore difficult to disentangle (3) the same prosodic feature may be involved in ‘doing’ more than one thing at the same time – for example a given pitch movement may be simultaneously involved in accentuation and demarcation (4) nearly all prosodic features – including pitch level – are subject to gradient variation and can be used to carry signals that many analysts would consider paralinguistic rather than linguistic (cf discussion in Ladd 1996: 33-41). Due to such factors, suggestions as to the meanings of RVE prosodic forms will be tentative and restricted to discourse functions such as the segmenting, structuring and highlighting of information. -

University of California Santa Cruz Minimal Reduplication

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ MINIMAL REDUPLICATION A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in LINGUISTICS by Jesse Saba Kirchner June 2010 The Dissertation of Jesse Saba Kirchner is approved: Professor Armin Mester, Chair Professor Jaye Padgett Professor Junko Ito Tyrus Miller Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Copyright © by Jesse Saba Kirchner 2010 Some rights reserved: see Appendix E. Contents Abstract vi Dedication viii Acknowledgments ix 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Structureofthethesis ...... ....... ....... ....... ........ 2 1.2 Overviewofthetheory...... ....... ....... ....... .. ....... 2 1.2.1 GoalsofMR ..................................... 3 1.2.2 Assumptionsandpredictions. ....... 7 1.3 MorphologicalReduplication . .......... 10 1.3.1 Fixedsize..................................... ... 11 1.3.2 Phonologicalopacity. ...... 17 1.3.3 Prominentmaterialpreferentiallycopied . ............ 22 1.3.4 Localityofreduplication. ........ 24 1.3.5 Iconicity ..................................... ... 24 1.4 Syntacticreduplication. .......... 26 2 Morphological reduplication 30 2.1 Casestudy:Kwak’wala ...... ....... ....... ....... .. ....... 31 2.2 Data............................................ ... 33 2.2.1 Phonology ..................................... .. 33 2.2.2 Morphophonology ............................... ... 40 2.2.3 -mut’ .......................................... 40 2.3 Analysis........................................ ..... 48 2.3.1 Lengtheningandreduplication. -

Options for a National Culture Symbol of Cameroon: Can the Bamenda Grassfields Traditional Dress Fit?

EAS Journal of Humanities and Cultural Studies Abbreviated Key Title: EAS J Humanit Cult Stud ISSN: 2663-0958 (Print) & ISSN: 2663-6743 (Online) Published By East African Scholars Publisher, Kenya Volume-2 | Issue-1| Jan-Feb-2020 | DOI: 10.36349/easjhcs.2020.v02i01.003 Research Article Options for a National Culture Symbol of Cameroon: Can the Bamenda Grassfields Traditional Dress Fit? Venantius Kum NGWOH Ph.D* Department of History Faculty of Arts University of Buea, Cameroon Abstract: The national symbols of Cameroon like flag, anthem, coat of arms and seal do not Article History in any way reveal her cultural background because of the political inclination of these signs. Received: 14.01.2020 In global sporting events and gatherings like World Cup and international conferences Accepted: 28.12.2020 respectively, participants who appear in traditional costume usually easily reveal their Published: 17.02.2020 nationalities. The Ghanaian Kente, Kenyan Kitenge, Nigerian Yoruba outfit, Moroccan Journal homepage: Djellaba or Indian Dhoti serve as national cultural insignia of their respective countries. The https://www.easpublisher.com/easjhcs reason why Cameroon is referred in tourist circles as a cultural mosaic is that she harbours numerous strands of culture including indigenous, Gaullist or Francophone and Anglo- Quick Response Code Saxon or Anglophone. Although aspects of indigenous culture, which have been grouped into four spheres, namely Fang-Beti, Grassfields, Sawa and Sudano-Sahelian, are dotted all over the country in multiple ways, Cameroon cannot still boast of a national culture emblem. The purpose of this article is to define the major components of a Cameroonian national culture and further identify which of them can be used as an acceptable domestic cultural device. -

Recognition of Nasalized and Non- Nasalized Vowels

RECOGNITION OF NASALIZED AND NON- NASALIZED VOWELS Submitted By: BILAL A. RAJA Advised by: Dr. Carol Espy Wilson and Tarun Pruthi Speech Communication Lab, Dept of Electrical & Computer Engineering University of Maryland, College Park Maryland Engineering Research Internship Teams (MERIT) Program 2006 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1- Abstract 3 2- What Is Nasalization? 3 2.1 – Production of Nasal Sound 3 2.2 – Common Spectral Characteristics of Nasalization 4 3 – Expected Results 6 3.1 – Related Previous Researches 6 3.2 – Hypothesis 7 4- Method 7 4.1 – The Task 7 4.2 – The Technique Used 8 4.3 – HMM Tool Kit (HTK) 8 4.3.1 – Data Preparation 9 4.3.2 – Training 9 4.3.3 – Testing 9 4.3.4 – Analysis 9 5 – Results 10 5.1 – Experiment 1 11 5.2 – Experiment 2 11 6 – Conclusion 12 7- References 13 2 1 - ABSTRACT When vowels are adjacent to nasal consonants (/m,n,ng/), they often become nasalized for at least some part of their duration. This nasalization is known to lead to changes in perceived vowel quality. The goal of this project is to verify if it is beneficial to first recognize nasalization in vowels and treat the three groups of vowels (those occurring before nasal consonants, those occurring after nasal consonants, and the oral vowels which are vowels that are not adjacent to nasal consonants) separately rather than collectively for recognizing the vowel identities. The standard Mel-Frequency Cepstral Coefficients (MFCCs) and the Hidden Markov Model (HMM) paradigm have been used for this purpose. The results show that when the system is trained on vowels in general, the recognition of nasalized vowels is 17% below that of oral vowels. -

507 the Effect of Lingua Franca (Persian) on Minority Languages

ISSN 2039‐2117 Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences Vol. 3 (2) May 2012 The Effect of Lingua Franca (Persian) on Minority Languages (Kurdish) Mahnaz Saiedi Payman Rezvani Department of English language, Tabriz branch, Islamic Azad University, Tabriz,Iran Doi:10.5901/mjss.2012.v3n2.507 Abstract The present study aims to consider the effect of lingua franca a sample of which is Persian upon minority languages as Kurdish which is spoken in a place where both Azari and Kurd-ish people have to communicate but by means of a third language (Persian) .the lexicon ,syntactical and phonological features of Kurdish in the local areas based on gathered data have been studied. The data gathered by questionnaire and recorded sounds along with in-terview with the local people, in particular literate ones who had the greatest exposure to the third language (lingua franca). The researcher could find significant changes which were traced to the impact of Persian as lingua franca in the region. This research is an innovation in its own kind and helps those who follow lingua franca and language changes and try to find any relations of which with linguistic purposes as well as language teaching. Keywords: lingua franca, Persian, Kurdish, phonology, lexicon 1. Introduction The present study aims to consider the linguistic influence of official standard Persian (as lingua franca) on non-official languages, Kurdish and Turkish, across the Western Azerbai-jan province. Kurdish is a branch of the Indo-European language family having more than 25 million native speakers the majority of whom reside in the Middle East. -

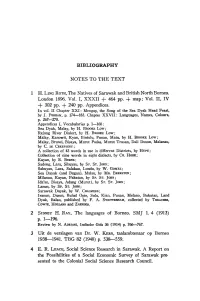

BIBLIOGRAPHY NOTES to the TEXT 1 H. LING ROTH, the Natives

BIBLIOGRAPHY NOTES TO THE TEXT 1 H. LING ROTH, The Natives of Sarawak and British North Borneo. London 18%. Vol. I, XXXII + 464 pp. + map; Vol. II, IV + 302 pp. + 240 pp. Appendices. In vol. II Chapter XXI: Mengap, the Song of the Sea Dyak Head Feast, by J. PERHAM, p. 174-183. Chapter XXVII: Languages, Names, Colours, p.267-278. Appendices I, Vocabularies p. 1-160: Sea Dyak, Malay, by H. BROOKE Low; Rejang River Dialect, by H. BROOKE Low; Malay, Kanowit, Kyan, Bintulu, Punan, Matu, by H. BROOKE Low; Malay, Brunei, Bisaya, Murut Padas, Murut Trusan, Dali Dusun, Malanau, by C. DE CRESPIGNY; A collection of 43 words in use in different Districts, by HUPE; Collection of nine words in eight dialects, by CH. HOSE; Kayan, by R. BURNS; Sadong, Lara, Sibuyau, by SP. ST. JOHN; Sabuyau, Lara, Salakau, Lundu, by W. GoMEZ; Sea Dayak (and Bugau), Malau, by MR. BRERETON; Milanau, Kayan, Pakatan, by SP. ST. JOHN; Ida'an, Bisaya, Adang (Murut), by SP. ST. JOlIN; Lanun, by SP. ST. JOHN; Sarawak Dayak, by W. CHALMERS; Iranun, Dusun, Bulud Opie, Sulu, Kian, Punan, Melano, Bukutan, Land Dyak, Balau, published by F. A. SWETTENHAM, collected by TREACHER, COWIE, HOLLAND and ZAENDER. 2 SIDNEY H. RAY, The languages of Borneo. SMJ 1. 4 (1913) p.1-1%. Review by N. ADRIANI, Indische Gids 36 (1914) p. 766-767. 3 Uit de verslagen van Dr. W. KERN, taalambtenaar op Borneo 1938-1941. TBG 82 (1948) p. 538---559. 4 E. R. LEACH, Social Science Research in Sarawak. A Report on the Possibilities of a Social Economic Survey of Sarawak pre sented to the Colonial Social Science Research Council. -

The Production of Lexical Tone in Croatian

The production of lexical tone in Croatian Inauguraldissertation zur Erlangung des Grades eines Doktors der Philosophie im Fachbereich Sprach- und Kulturwissenschaften der Johann Wolfgang Goethe-Universität zu Frankfurt am Main vorgelegt von Jevgenij Zintchenko Jurlina aus Kiew 2018 (Einreichungsjahr) 2019 (Erscheinungsjahr) 1. Gutacher: Prof. Dr. Henning Reetz 2. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Sven Grawunder Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 01.11.2018 ABSTRACT Jevgenij Zintchenko Jurlina: The production of lexical tone in Croatian (Under the direction of Prof. Dr. Henning Reetz and Prof. Dr. Sven Grawunder) This dissertation is an investigation of pitch accent, or lexical tone, in standard Croatian. The first chapter presents an in-depth overview of the history of the Croatian language, its relationship to Serbo-Croatian, its dialect groups and pronunciation variants, and general phonology. The second chapter explains the difference between various types of prosodic prominence and describes systems of pitch accent in various languages from different parts of the world: Yucatec Maya, Lithuanian and Limburgian. Following is a detailed account of the history of tone in Serbo-Croatian and Croatian, the specifics of its tonal system, intonational phonology and finally, a review of the most prominent phonetic investigations of tone in that language. The focal point of this dissertation is a production experiment, in which ten native speakers of Croatian from the region of Slavonia were recorded. The material recorded included a diverse selection of monosyllabic, bisyllabic, trisyllabic and quadrisyllabic words, containing all four accents of standard Croatian: short falling, long falling, short rising and long rising. Each target word was spoken in initial, medial and final positions of natural Croatian sentences. -

NWAV 46 Booklet-Oct29

1 PROGRAM BOOKLET October 29, 2017 CONTENTS • The venue and the town • The program • Welcome to NWAV 46 • The team and the reviewers • Sponsors and Book Exhibitors • Student Travel Awards https://english.wisc.edu/nwav46/ • Abstracts o Plenaries Workshops o nwav46 o Panels o Posters and oral presentations • Best student paper and poster @nwav46 • NWAV sexual harassment policy • Participant email addresses Look, folks, this is an electronic booklet. This Table of Contents gives you clues for what to search for and we trust that’s all you need. 2 We’ll have buttons with sets of pronouns … and some with a blank space to write in your own set. 3 The venue and the town We’re assuming you’ll navigate using electronic devices, but here’s some basic info. Here’s a good campus map: http://map.wisc.edu/. The conference will be in Union South, in red below, except for Saturday talks, which will be in the Brogden Psychology Building, just across Johnson Street to the northeast on the map. There are a few places to grab a bite or a drink near Union South and the big concentration of places is on and near State Street, a pedestrian zone that runs east from Memorial Library (top right). 4 The program 5 NWAV 46 2017 Madison, WI Thursday, November 2nd, 2017 12:00 Registration – 5th Quarter Room, Union South pm-6:00 pm Industry Landmark Northwoods Agriculture 1:00- Progress in regression: Discourse analysis for Sociolinguistics and Texts as data 3:00 Statistical and practical variationists forensic speech sources for improvements to Rbrul science: Knowledge- -

The Position of Enggano Within Austronesian

7KH3RVLWLRQRI(QJJDQRZLWKLQ$XVWURQHVLDQ 2ZHQ(GZDUGV Oceanic Linguistics, Volume 54, Number 1, June 2015, pp. 54-109 (Article) 3XEOLVKHGE\8QLYHUVLW\RI+DZDL L3UHVV For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/ol/summary/v054/54.1.edwards.html Access provided by Australian National University (24 Jul 2015 10:27 GMT) The Position of Enggano within Austronesian Owen Edwards AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY Questions have been raised about the precise genetic affiliation of the Enggano language of the Barrier Islands, Sumatra. Such questions have been largely based on Enggano’s lexicon, which shows little trace of an Austronesian heritage. In this paper, I examine a wider range of evidence and show that Enggano is clearly an Austronesian language of the Malayo-Polynesian (MP) subgroup. This is achieved through the establishment of regular sound correspondences between Enggano and Proto‒Malayo-Polynesian reconstructions in both the bound morphology and lexicon. I conclude by examining the possible relations of Enggano within MP and show that there is no good evidence of innovations shared between Enggano and any other MP language or subgroup. In the absence of such shared innovations, Enggano should be considered one of several primary branches of MP. 1. INTRODUCTION.1 Enggano is an Austronesian language spoken on the southernmost of the Barrier Islands off the west coast of the island of Sumatra in Indo- nesia; its location is marked by an arrow on map 1. The genetic position of Enggano has remained controversial and unresolved to this day. Two proposals regarding the genetic classification of Enggano have been made: 1.