Oral and Written Traditions of Buginese: Interpretation Writing Using the Buginese Language in South Sulawesi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Technical Report Phase I 1997-2001 Technical Report Phase I 1997-2001

cvr_itto 4/10/02 10:06 AM Page 1 Technical Report Phase I 1997-2001 Technical Technical Report Phase I 1997-2001 ITTO PROJECT PD 12/97 REV.1 (F) Forest, Science and Sustainability: The Bulungan Model Forest ITTO project PD 12/97 Rev. 1 (F) project PD 12/97 Rev. ITTO ITTO Copyright © 2002 International Tropical Timber Organization International Organization Center, 5th Floor Pacifico - Yokohama 1-1-1 Minato - Mirai, Nishi - ku Yokohama - City, Japan 220-0012 Tel. : +81 (45) 2231110; Fax: +81 (45) 2231110 E-mail: [email protected] Web site: http://www.itto.or.jp Center for International Forestry Research Mailing address: P.O. Box 6596 JKPWB, Jakarta 10065, Indonesia Office address: Jl. CIFOR, Situ Gede, Sindang Barang, Bogor Barat 16680, Indonesia Tel.: +62 (251) 622622; Fax: +62 (251) 622100 E-mail: [email protected] Web site: http://www.cifor.cgiar.org Financial support from the International Tropical Timber Organization (ITTO) through the Project PD 12/97 Rev.1 (F), Forest, Science and Sustainability: The Bulungan Model Forest is gratefully acknowledged ii chapter00 2 4/8/02, 2:50 PM Contents Acronyms and Abbreviations iv Foreword vi Acknowledgements viii Executive summary ix 1. Introduction 1 2. Overview of Approaches and Methods 4 3. General Description of the Bulungan Research Forest 8 4. Research on Logging 23 4.a. Comparison of Reduced-Impact Logging and Conventional Logging Techniques 23 4.b. Reduced-Impact Logging in Indonesian Borneo: Some Results Confirming the Need for New Silvicultural Prescriptions 26 4.c. Cost-benefit Analysis of Reduced-Impact Logging in a Lowland Dipterocarp Forest of Malinau, East Kalimantan 39 5. -

The Learning Model of Makassarese Language Based on the Character Building Concept

THE LEARNING MODEL OF MAKASSARESE LANGUAGE BASED ON THE CHARACTER BUILDING CONCEPT (Research and Development in Elementary School of Makassar City) 1 Sitti Rabiah 2 Faculty of Letter Universitas Muslim Indonesia Makassar, Indonesia Abstract Character building, nowadays become a matter of urgency and decisive for the future generation to meet the nation's golden years in 2045. In this period, the current generation is on early childhood education (PAUD), Elementary Education, Secondary Education, and Higher Education will entering productive age who decide this nation's strategic role at the age of 100 years of Indonesian independence in the year of 2045. In order to oversee this golden generation, it is necessary to reform the education sector which plays an important role in setting up and directing the excellent and productive human resources, and mastering in science, technology, and art is needed in this era of global competition. The effort to do that is to develop character values through a learning process, one through the Makassarese language learning. This effort is expected to provide supplies to students both Makassarese language skills on the one hand, and the formation of character on the other. Furthermore, this study aimed to develop instructional materials in Makassarese language learning in primary schools that integrates the values of character. This study refers to the steps of research and development by Borg and Gall, and collaborated with the research phase by Brown to produce Makassarese language textbooks based on character building concept. Keywords: Learning Model, Makassarese Language, Character Building, Elementary School Abstrak Penanaman karakter, dewasa ini menjadi hal yang mendesak dan menentukan untuk masa depan bangsa menyongsong generasi emas tahun 2045. -

05-06 2013 GPD Insides.Indd

Front Cover [Do not print] Replace with page 1 of cover PDF WILLIAM CAREY LIBRARY NEW RELEASE Developing Indigenous Leaders Lessons in Mission from Buddhist Asia (SEANET 10) Every movement is only one generation from dying out. Leadership development remains the critical issue for mission endeavors around the world. How are leaders developed from the local context for the local context? What is the role of the expatriate in this process? What models of hope are available for those seeking further direction in this area, particularly in mission to the Buddhist world of Asia? To answer these and several other questions, SEANET proudly presents the tenth volume in its series on practical missiology, Developing Indigenous Leaders: Lessons in Mission from Buddhist Asia. Each chapter in this volume is written by a practitioner and a mission scholar. Th e ten authors come from a wide range of ecclesial and national backgrounds and represent service in ten diff erent Buddhist contexts of Asia. With biblical integrity and cultural sensitivity, these chapters provide honest refl ection, insight, and guidance. Th ere is perhaps no more crucial issue than the development of dedicated indigenous leaders who will remain long after missionaries have returned home. If you are concerned about raising up leaders in your ministry in whatever cultural context it may be, this volume will be an important addition to your library. ISBN: 978-0-87808-040-3 List Price: $17.99 Paul H. De Neui Our Price: $14.39 WCL | Pages 243 | Paperback 2013 3 or more: $9.89 www.missionbooks.org 1-800-MISSION Become a Daily World Christian What is the Global Prayer Digest? Loose Change Adds Up! Th e Global Prayer Digest is a unique devotion- In adapting the Burma Plan to our culture, al booklet. -

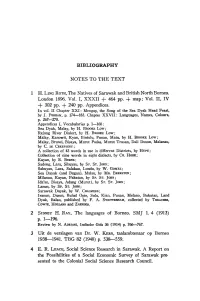

BIBLIOGRAPHY NOTES to the TEXT 1 H. LING ROTH, the Natives

BIBLIOGRAPHY NOTES TO THE TEXT 1 H. LING ROTH, The Natives of Sarawak and British North Borneo. London 18%. Vol. I, XXXII + 464 pp. + map; Vol. II, IV + 302 pp. + 240 pp. Appendices. In vol. II Chapter XXI: Mengap, the Song of the Sea Dyak Head Feast, by J. PERHAM, p. 174-183. Chapter XXVII: Languages, Names, Colours, p.267-278. Appendices I, Vocabularies p. 1-160: Sea Dyak, Malay, by H. BROOKE Low; Rejang River Dialect, by H. BROOKE Low; Malay, Kanowit, Kyan, Bintulu, Punan, Matu, by H. BROOKE Low; Malay, Brunei, Bisaya, Murut Padas, Murut Trusan, Dali Dusun, Malanau, by C. DE CRESPIGNY; A collection of 43 words in use in different Districts, by HUPE; Collection of nine words in eight dialects, by CH. HOSE; Kayan, by R. BURNS; Sadong, Lara, Sibuyau, by SP. ST. JOHN; Sabuyau, Lara, Salakau, Lundu, by W. GoMEZ; Sea Dayak (and Bugau), Malau, by MR. BRERETON; Milanau, Kayan, Pakatan, by SP. ST. JOHN; Ida'an, Bisaya, Adang (Murut), by SP. ST. JOlIN; Lanun, by SP. ST. JOHN; Sarawak Dayak, by W. CHALMERS; Iranun, Dusun, Bulud Opie, Sulu, Kian, Punan, Melano, Bukutan, Land Dyak, Balau, published by F. A. SWETTENHAM, collected by TREACHER, COWIE, HOLLAND and ZAENDER. 2 SIDNEY H. RAY, The languages of Borneo. SMJ 1. 4 (1913) p.1-1%. Review by N. ADRIANI, Indische Gids 36 (1914) p. 766-767. 3 Uit de verslagen van Dr. W. KERN, taalambtenaar op Borneo 1938-1941. TBG 82 (1948) p. 538---559. 4 E. R. LEACH, Social Science Research in Sarawak. A Report on the Possibilities of a Social Economic Survey of Sarawak pre sented to the Colonial Social Science Research Council. -

Of ODOARDOBECCARI Dedication

1864 1906 1918 Dedicated to the memory of ODOARDOBECCARI Dedication A dedication to ODOARDO BECCARI, the greatest botanist ever to study in Malesia, is long overdue. Although best known as a plant taxonomist, his versatile genius extended far beyond the basic field ofthis branch ofBotany, his wide interest leading him to investigate the laws ofevolution, the interrelations between plants and animals, the connection between vegetation and environ- cultivated ment, plant distribution, the and useful plants of Malesia and many other problems of life. plant But, even if he devoted his studies to plants, in the depth of his mind he was primarily a naturalist, and in his long, lonely and dangerousexplorations in Malesia he was attracted to all aspects ofnature and human life, assembling, besides plants, an incredibly large number of collec- tions and an invaluable wealth ofdrawings and observations in zoology, anthropologyand ethnol- He ogy. was indeed a naturalist, and one of the greatest of his time; but never in his mind were the knowledge and beauty of Nature disjoined, and, as he was a true and complete naturalist, he the time was at same a poet and an artist. His Nelleforestedi Borneo, Viaggi ericerche di un mturalista(1902), excellently translatedinto English (in a somewhatabbreviated form) by Prof. E. GioLiouandrevised and edited by F.H.H. Guillemardas Wanderingsin the great forests of Borneo (1904), is a treasure in tropical botany; it is in fact an unrivalledintroductionto tropical plant lifeand animals, man included. It is a most readable book touching on all sorts of topics and we advise it to be studied by all young people whose ambition it is to devote their life to tropical research. -

Learn Thai Language in Malaysia

Learn thai language in malaysia Continue Learning in Japan - Shinjuku Japan Language Research Institute in Japan Briefing Workshop is back. This time we are with Shinjuku of the Japanese Language Institute (SNG) to give a briefing for our students, on learning Japanese in Japan.You will not only learn the language, but you will ... Or nearby, the Thailand- Malaysia border. Almost one million Thai Muslims live in this subregion, which is a belief, and learn how, to grow other (besides rice) crops for which there is a good market; Thai, this term literally means visitor, ASEAN identity, are we there yet? Poll by Thai Tertiary Students ' Sociolinguistic. Views on the ASEAN community. Nussara Waddsorn. The Assumption University usually introduces and offers as a mandatory optional or free optional foreign language course in the state-higher Japanese, German, Spanish and Thai languages of Malaysia. In what part students find it easy or difficult to learn, taking Mandarin READING HABITS AND ATTITUDES OF THAI L2 STUDENTS from MICHAEL JOHN STRAUSS, presented partly to meet the requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS (TESOL) I was able to learn Thai with Sukothai, where you can learn a lot about the deep history of Thailand and culture. Be sure to read the guide and learn a little about the story before you go. Also consider visiting neighboring countries like Cambodia, Vietnam and Malaysia. Air LANGUAGE: Thai, English, Bangkok TYPE OF GOVERNMENT: Constitutional Monarchy CURRENCY: Bath (THB) TIME ZONE: GMT No 7 Thailand invites you to escape into a world of exotic enchantment and excitement, from the Malaysian peninsula. -

Regional Language Learning in Regional Multilingual Classes: Problems and Handling

Universal Journal of Educational Research 8(11): 5299-5304, 2020 http://www.hrpub.org DOI: 10.13189/ujer.2020.081130 Regional Language Learning in Regional Multilingual Classes: Problems and Handling Abdul Kadir1, Aziz Thaba2,*, Munirah3, Sitti Aida Azis3, Rukayah4 1Cokroaminoto College of Teacher Training and Education of Pinrang, Indonesia 2Lembaga Swadaya Penelitian dan Pengembangan Pendidikan (LSP3) Matutu, Indonesia 3Muhammadiyah University of Makassar, Indonesia 4State University of Makassar, Indonesia Received July 12, 2020; Revised August 14, 2020; Accepted September 17, 2020 Cite This Paper in the following Citation Styles (a): [1] Abdul Kadir, Aziz Thaba, Munirah, Sitti Aida Azis, Rukayah , "Regional Language Learning in Regional Multilingual Classes: Problems and Handling," Universal Journal of Educational Research, Vol. 8, No. 11, pp. 5299 - 5304, 2020. DOI: 10.13189/ujer.2020.081130. (b): Abdul Kadir, Aziz Thaba, Munirah, Sitti Aida Azis, Rukayah (2020). Regional Language Learning in Regional Multilingual Classes: Problems and Handling. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 8(11), 5299 - 5304. DOI: 10.13189/ujer.2020.081130. Copyright©2020 by authors, all rights reserved. Authors agree that this article remains permanently open access under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 International License Abstract Local languages are a part of the national understanding and perceptions in teaching on classroom education curriculum that is taught in schools. In its dynamics and diversity, designing learning classroom process, the curriculum of local language teaching and management with balanced interactions, integrating learning still faces various problems that hinder achieving learning processes between students using a collaborative the intended goals. One of the problems is the multicultural model, and designing a balanced evaluation. -

The Bungku-Tolaki Languages of South-Eastern Sulawesi, Indonesia

The Bungku-Tolaki languages of South-Eastern Sulawesi, Indonesia Mead, D.E. The Bungku-Tolaki languages of south-eastern Sulawesi, Indonesia. D-91, xi + 188 pages. Pacific Linguistics, The Australian National University, 1999. DOI:10.15144/PL-D91.cover ©1999 Pacific Linguistics and/or the author(s). Online edition licensed 2015 CC BY-SA 4.0, with permission of PL. A sealang.net/CRCL initiative. PACIFIC LINGUISTICS FOUNDING EDITOR: Stephen A. Wurm EDITORIAL BOARD: Malcolm D. Ross and Darrell T. Tryon (Managing Editors), John Bowden, Thomas E. Dutton, Andrew K. Pawley Pacific Linguistics is a publisher specialising in linguistic descriptions, dictionaries, atlases and other material on languages of the Pacific, the Philippines, Indonesia and Southeast Asia. The authors and editors of Pacific Linguistics publications are drawn from a wide range of institutions around the world. Pacific Linguistics is associated with the Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies at The Australian National University. Pacific Linguistics was established in 1963 through an initial grant from the Hunter Douglas Fund. It is a non-profit-making body financed largely from the sales of its books to libraries and individuals throughout the world, with some assistance from the School. The Editorial Board of Pacific Linguistics is made up of the academic staff of the School's Department of Linguistics. The Board also appoints a body of editorial advisors drawn from the international community of linguists. Publications in Series A, B and C and textbooks in Series D are refereed by scholars with relevant expertise who are normally not members of the editorial board. -

The Indication of Sundanese Banten Dialect Shift in Tourism Area As Banten Society’S Identity Crisis (Sociolinguistics Study in Tanjung Lesung and Carita Beach)

International Seminar on Sociolinguistics and Dialectology: Identity, Attitude, and Language Variation “Changes and Development of Language in Social Life” 2017 THE INDICATION OF SUNDANESE BANTEN DIALECT SHIFT IN TOURISM AREA AS BANTEN SOCIETY’S IDENTITY CRISIS (SOCIOLINGUISTICS STUDY IN TANJUNG LESUNG AND CARITA BEACH) Alya Fauzia Khansa, Dilla Erlina Afriliani, Siti Rohmatiah Universitas Pendidikan Indonesia [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] ABSTRACT This research used theoretical sociolinguistics and descriptive qualitative approaches. The location of this study is Tanjung Lesung and Carita Beach tourism area, Pandeglang, Banten. The subject of this study is focused on Tanjung Lesung and Carita Beach people who understand and use Sundanese Banten dialect and Indonesian language in daily activity. The subject consists of 55 respondents based on education level, age, and gender categories. The data taken were Sundanese Banten dialect speech act by the respondents, both literal and non-literal speech, the information given is the indication of Sundanese Banten dialect shift factors. Data collection technique in this research is triangulation (combination) in the form of participative observation, documentation, and deep interview by using “Basa Urang Project” instrument. This research reveals that the problems related to the indication of Sundanese Banten dialect shift in Tanjung Lesung and Banten Carita Beach which causes identity crisis to Tanjung Lesung and Banten Carita Beach people. This study discovers (1) description of Bantenese people local identity, (2) perception of Tanjung Lesung and Carita Beach people on the use of Sundanese Banten dialect in Tanjung Lesung and Carita Beach tourism area and (3) the indications of Sundanese Banten dialect shift in Tanjung Lesung and Carita Beach tourism area. -

Inventory of the Oriental Manuscripts of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences in Amsterdam

INVENTORIES OF COLLECTIONS OF ORIENTAL MANUSCRIPTS INVENTORY OF THE ORIENTAL MANUSCRIPTS OF THE ROYAL NETHERLANDS ACADEMY OF ARTS AND SCIENCES IN AMSTERDAM COMPILED BY JAN JUST WITKAM PROFESSOR OF PALEOGRAPHY AND CODICOLOGY IN LEIDEN UNIVERSITY INTERPRES LEGATI WARNERIANI TER LUGT PRESS LEIDEN 2006 Inventory of the Oriental manuscripts in the Royal Academy in Amsterdam 2 © Copyright by Jan Just Witkam & Ter Lugt Press, Leiden, The Netherlands, 2006. The form and contents of the present inventory are protected by Dutch and international copyright law and database legislation. All use other than within the framework of the law is forbidden and liable to prosecution. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission of the author and the publisher. First electronic publication: 12 February 2006 Latest update: 23 December 2006 © Copyright by Jan Just Witkam & Ter Lugt Press, Leiden, The Netherlands, 2006. Inventory of the Oriental manuscripts in the Royal Academy in Amsterdam 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction Inventory of the Oriental Manuscripts of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences in Amsterdam Bibliography Index of languages Conversion table for De Jongs catalogue © Copyright by Jan Just Witkam & Ter Lugt Press, Leiden, The Netherlands, 2006. Inventory of the Oriental manuscripts in the Royal Academy in Amsterdam 4 Introduction The Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences (Koninklijke Nederlandse Akademie van Wetenschappen) in Amsterdam owns a modest collection of Oriental manuscripts. The majority of these are on permanent loan in Leiden University Library. -

Bugis Migration Various Continues and Success

Bugis Migration Various Continues and Success, Rahmawati| 373 Journal of Research and Multidisciplinary ISSN: 2622-9536 Print ISSN: 2622-9544 Online http://journal.alhikam.net/index.php/jrm Volume 3, Issue 2, September 2020, Pages 373-384 Bugis Migration Various Continues and Success Rahmawati Lecturer at the Faculty of Adab and Humanities UIN Alauddin Makassar, Indonesia Email: [email protected] Abstract This article discusses the migration process of the Bugis people in various regions. To reach a bright spot in this study, the authors use historical, sociological, anthropological studies, and writings supporting this paper to complete the desired information. This study's results revealed that the Bugis people's desire to migrate because of the real situation that allows them to migrate. This can be seen at least in two ways, namely the sociological reality and psychological reality. Sociological Realityin In the middle of Islamization's process related to the Gowa Kingdom Political movement to subdue the kingdoms that did not yet embrace Islam. Psychological reality because of the chaos that was allegedly hurting his survival. Population movements carried out by Bugis communities in various regions turned out to be able to provide a positive impact on their migration. The most scientific thing to provide evidence of the Bugis migrating community's success is to look at the highest position held in the area of migration. They can also form their ethnicity without changing or hurting the culture that already exists in each region where they migrate. Keywords: Migration, Success, Bugis Introduction Regarding the nature of migration or overseas Bugis people are already widely told in various writings that always refer to the epic La Galigo. -

Research Article Traditional Houses and Projective Geometry: Building Numbers and Projective Coordinates

Hindawi Journal of Applied Mathematics Volume 2021, Article ID 9928900, 25 pages https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/9928900 Research Article Traditional Houses and Projective Geometry: Building Numbers and Projective Coordinates Wen-Haw Chen 1 and Ja’faruddin 1,2 1Department of Applied Mathematics, Tunghai University, Taichung 407224, Taiwan 2Department of Mathematics, Universitas Negeri Makassar, Makassar 90221, Indonesia Correspondence should be addressed to Ja’faruddin; [email protected] Received 6 March 2021; Accepted 27 July 2021; Published 1 September 2021 Academic Editor: Md Sazzad Hossien Chowdhury Copyright © 2021 Wen-Haw Chen and Ja’faruddin. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. The natural mathematical abilities of humans have advanced civilizations. These abilities have been demonstrated in cultural heritage, especially traditional houses, which display evidence of an intuitive mathematics ability. Tribes around the world have built traditional houses with unique styles. The present study involved the collection of data from documentation, observation, and interview. The observations of several traditional buildings in Indonesia were based on camera images, aerial camera images, and documentation techniques. We first analyzed the images of some sample of the traditional houses in Indonesia using projective geometry and simple house theory and then formulated the definitions of building numbers and projective coordinates. The sample of the traditional houses is divided into two categories which are stilt houses and nonstilt house. The present article presents 7 types of simple houses, 21 building numbers, and 9 projective coordinates.