N E W S L E T T

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Margot Harley & David Schramm

THE SHAKESPEARE GUILD INVITES YOU TO TALK WITH TWO STELLAR ARTISTS PRESENTED AT THE National Arts Club UNDER THE SPONSORSHIP OF MagRack Video IN ASSOCIATION WITH THE English-Speaking Union MARGOT HARLEY & DAVID SCHRAMM Monday, April 28, at 8:00 p.m. This conversation will celebrate the thirtieth-anniversary season of THE ACTING COMPANY, a troupe that MARGOT HARLEY co-founded with the late JOHN HOUSE- MAN in 1972 as a way to allow the JUILLIARD SCHOOL DRAMA DIVISION’s first graduating class (which included KEVIN KLINE, PATTI LUPONE, and DAVID OGDEN STIERS) to gain professional experience in classical theater. Ms. Harley administered the Juilliard program during its first twelve years. Meanwhile she has produced such hits as Max Blitzstein’s musical The Cradle Will Rock (a celebrated Houseman revival that went from Manhattan to London’s Old Vic), The Curse of an Aching Heart and The Robber Bridegroom (two Broadway shows that starred Faye Dunaway), Ten by Tennes- see (a two-evening retrospective of Williams’ one-act plays, directed by Michael Kahn), and the New York premiere of Eric Overymyer’s On the Verge (directed by Garland Wright). She’ll be joined by DAVID SCHRAMM, another of her first-year Juilliard alumni. Mr. Schramm’s Broadway credits include Bedroom Farce, Goodbye Fidel, Lon- don Assurance, The Misanthrope, The Robber Bridegroom, School for Scandal, Tartuffe Born Again, and The Three Sisters. Best known for his eight seasons as Roy Biggins, the brash and overbearing owner of a commuter airline in the NBC sitcom Wings (1990-97), Mr. Schramm has also starred in Another World, Jake and the Fatman, Wiseguy, The Equalizer, Miami Vice, Spencer for Hire, and- Working Girl (where he played Joe McGill, opposite actress Sandra Bullock), and in such films as A Shock to the System, Big Packages, Johnny Handsome, Let it Ride, and Ragtime. -

5. Calling for International Solidarity: Hanns Eisler’S Mass Songs in the Soviet Union

From Massenlieder to Massovaia Pesnia: Musical Exchanges between Communists and Socialists of Weimar Germany and the Early Soviet Union by Yana Alexandrovna Lowry Department of Music Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Bryan Gilliam, Supervisor ___________________________ Edna Andrews ___________________________ John Supko ___________________________ Jacqueline Waeber Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music in the Graduate School of Duke University 2014 i v ABSTRACT From Massenlieder to Massovaia Pesnia: Musical Exchanges between Communists and Socialists of Weimar Germany and the Early Soviet Union by Yana Alexandrovna Lowry Department of Music Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Bryan Gilliam, Supervisor ___________________________ Edna Andrews ___________________________ John Supko ___________________________ Jacqueline Waeber An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music in the Graduate School of Duke University 2014 Copyright by Yana Alexandrovna Lowry 2014 Abstract Group songs with direct political messages rose to enormous popularity during the interwar period (1918-1939), particularly in recently-defeated Germany and in the newly- established Soviet Union. This dissertation explores the musical relationship between these two troubled countries and aims to explain the similarities and differences in their approaches to collective singing. The discussion of the very complex and problematic relationship between the German left and the Soviet government sets the framework for the analysis of music. Beginning in late 1920s, as a result of Stalin’s abandonment of the international revolutionary cause, the divergences between the policies of the Soviet government and utopian aims of the German communist party can be traced in the musical propaganda of both countries. -

South Coast Repertory Is a Professional Resident Theatre Founded in 1964 by David Emmes and Martin Benson

IN BRIEF FOUNDING South Coast Repertory is a professional resident theatre founded in 1964 by David Emmes and Martin Benson. VISION Creating the finest theatre in America. LEADERSHIP SCR is led by Artistic Director David Ivers and Managing Director Paula Tomei. Its 33-member Board of Trustees is made up of community leaders from business, civic and arts backgrounds. In addition, hundreds of volunteers assist the theatre in reaching its goals, and about 2,000 individuals and businesses contribute each year to SCR’s annual and endowment funds. MISSION South Coast Repertory was founded in the belief that theatre is an art form with a unique power to illuminate the human experience. We commit ourselves to exploring urgent human and social issues of our time, and to merging literature, design, and performance in ways that test the bounds of theatre’s artistic possibilities. We undertake to advance the art of theatre in the service of our community, and aim to extend that service through educational, intercultural, and community engagement programs that harmonize with our artistic mission. FACILITY/ The David Emmes/Martin Benson Theatre Center is a three-theatre complex. Prior to the pandemic, there were six SEASON annual productions on the 507-seat Segerstrom Stage, four on the 336-seat Julianne Argyros Stage, with numerous workshops and theatre conservatory performances held in the 94-seat Nicholas Studio. In addition, the three-play family series, “Theatre for Young Audiences,” produced on the Julianne Argyros Stage. The 20-21 season includes two virtual offerings and a new outdoors initiative, OUTSIDE SCR, which will feature two productions in rotating rep at the Mission San Juan Capistrano in July 2021. -

Traum Und Abgrund Das Leben Der Schauspielerin Carola Neher Von Marianne Thoms

SWR2 MANUSKRIPT ESSAYS FEATURES KOMMENTARE VORTRÄGE SWR2 Wissen Traum und Abgrund Das Leben der Schauspielerin Carola Neher Von Marianne Thoms Carola Neher, eine Lieblingsschauspielerin Bert Brechts, flieht vor den Nazis nach Moskau, gerät in stalinistischen Terror und stirbt, nach fünf Jahren Lagerhaft, entkräftet an Typhus. Sendung: Freitag, 28. September 2012, 8.30 – 8.58 Uhr Wiederholung, Donnerstag, 02.08.2018 Redaktion: Udo Zindel Regie: Andrea Leclerque Produktion: SWR 2012 Bitte beachten Sie: Das Manuskript ist ausschließlich zum persönlichen, privaten Gebrauch bestimmt. Jede weitere Vervielfältigung und Verbreitung bedarf der ausdrücklichen Genehmigung des Urhebers bzw. des SWR. MANUSKRIPT Regie: Musikblende Klaviermusik Chopin, darüber sprechen: Carola: Man nehme eine beliebige schöne Frau und lasse sie über die Bühne gehen. Sie wird über ihre eigenen Beine und Gedanken stolpern. Sie ist aus ihrem Element gekommen, ein Fisch auf dem Land. Aber wir Schauspielerinnen sind erst auf der Bühne in unserem Element – wir stolpern nur im Leben. Ansager.: Traum und Abgrund – Das Leben der Schauspielerin Carola Neher, 1900 bis 1942. Eine Sendung von Marianne Thoms. Sprecherin: 1 Die gebürtige Münchnerin ist schön, intelligent und hochbegabt. Schon als Kind träumt sich Carola Neher in die Welt des Theaters. Niemand kann sie aufhalten – weder ihr herrschsüchtiger Vater, ein Musiker, noch die besorgte Mutter, eine Gastwirtin. Ihr Bruder Josef sagt über sie: Zitator: Die wäre in jedem Fall Schauspielerin geworden. Und wenn sie im nächsten Jahr daran gestorben wäre. Sprecherin: Mit hemmungslos vitaler Darstellungslust erobert Carola Neher ab ihrem 20. Lebensjahr Bühne für Bühne: Baden-Baden, Nürnberg, München, Breslau – immer zielstrebig mit dem Blick auf Berlin. Mit frechem Vergnügen nutzt sie auch ihre Anziehungskraft auf Männer. -

Acting in the Academy

Acting in the Academy There are over 150 BFA and MFA acting programs in the US today, nearly all of which claim to prepare students for theatre careers. Peter Zazzali contends that these curricula represent an ethos that is outdated and limited given today’s shrinking job market for stage actors. Acting in the Academy traces the history of actor training in universities to make the case for a move beyond standard courses in voice and speech, move- ment, or performance, to develop an entrepreneurial model that motivates and encourages students to create their own employment opportunities. This book answers questions such as: • How has the League of Professional Theatre Training Programs shaped actor training in the US? • How have training programs and the acting profession developed in relation to one another? • What impact have these developments had on American acting as an art form? Acting in the Academy calls for a reconceptualization of actor training in the US, and looks to newly empower students of performance with a fresh, original perspective on their professional development. Peter Zazzali is Assistant Professor of Theatre at the University of Kansas. John Houseman and members of Group I at Juilliard in the spring of 1972 reading positive reviews of the Acting Company’s inaugural season. Kevin Kline is seated behind Houseman. Photo by Raimondo Borea; Courtesy of the Juilliard School Archives. Acting in the Academy The history of professional actor training in US higher education Peter Zazzali First published 2016 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN and by Routledge 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2016 Peter Zazzali The right of Peter Zazzali to be identifi ed as author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. -

Moskau Mit Einem Lächeln. Annäherung an Die Schauspielerin

Christina Jung Moskau mit einem Lächeln Annäherung an die Schauspielerin Lotte Loebinger und das sowjetische Exil Verdammte Welt. Es bleibt ei- nem nur übrig, sich aufzuhängen oder sie zu ändern. Aus Hoppla, wir leben! (1927) letzte Schrifteinblendung Lotte Loebinger 9127 Mit Schiller, ihrer „große[n] Liebe, schon von der Schulzeit her“,1 fängt alles an. Die Eboli ist die Rolle, mit der Lotte Loebinger sich an verschiedenen Theatern vorstellt und genommen wird. Doch Klassiker zu spielen, wird ein Lebenstraum bleiben, wie sie rückblickend bemerkt. Zwar ist Schiller zum meist gespielten Dramatiker der 30er Jahre avanciert,2 Lotte Loebinger aber hat frühzeitig Partei ergriffen und sich für das politisch-revolutionäre Theater entschieden. Das hat den verstaubten Klassiker kurzfristig eingemottet3 und sich enthusiastisch der zeitgenössischen Dramatik gewidmet: Friedrich Wolf, Ernst Toller, Theodor Plivier und nicht zuletzt Brecht stehen auf dem Spiel- plan. Lotte Loebingers Karriere ist eng mit den großen, das Theater der Weima- 1 Waack, Renate: Lotte Loebinger. In: Pietzsch, Ingeborg: Garderobengespräche. Berlin (DDR) 1982. S. 91. 2 Vgl. Mittenzwei, Werner: Verfolgung und Vertreibung deutscher Bühnenkünstler durch den Nationalsozialismus. In: Mittenzwei, Werner/Trapp, Frithjof/Rischbieter, Henning/Schneider, Hansjörg (Hrsg.): Handbuch des deutschsprachigen Exiltheaters 1933-1945. München 1999. S. 23. 3 Ausnahmen bestätigen die Regel. So inszenierte z. B. Erwin Piscator 1926 Schillers Räuber für das Staatliche Schauspielhaus Berlin. Auch im Repertoire des deutschen Exiltheaters in der Sowjetunion machten klassische Dramen einen nicht unerheblichen Teil aus. 10 Augen-Blick 33: Flucht durch Europa rer Republik prägenden Namen verbunden: Allen voran mit Erwin Piscator, aber auch Gustav von Wangenheim und Maxim Vallentin, Regisseure, die auch für das Exiltheater, insbesondere in der Sowjetunion und später in der DDR von Bedeutung sind. -

1999 Winter Triangle Magazine

Profiles Excellenceof PRESIDENT’S REPORT 1999 From the President Good People Making Good Things Happen university can be no better than its people. In mission field in Athat regard, Indiana Wesleyan University Southern Africa truly is blessed. We are blessed one-hundred fold, and Cambodia indeed four-hundred fold. That’s how many for 14 years and people there now are in the IWU family: 430. had not In planning this issue of the Triangle, Alan considered the Miller gave our vice presidents a most difficult possibility of assignment. Alan, in his role as editor of the teaching at Triangle, asked each vice president to choose one IWU. Three person from his area of responsibility who years ago, he Dr. Jim Barnes demonstrated the excellent caliber of people who brought his twin work at IWU. sons to campus for a visit where he learned about That’s almost like asking a parent to pick one of an opening in the religion department. He was his or her children as examples of good kids. offered and accepted the job. Dr. Lo recently Employees at IWU are like family. began his fourth year as head of IWU’s (For the record, Wilbur and Ardelia Williams, intercultural studies program, which already has who are featured on the cover of this magazine, 70 students. weren’t involved in the selection process. They Two years ago, Dr. Harriet Rojas flew to were consensus choices to represent the very best Indianapolis to interview for a job at a state that IWU has to offer.) university – only to learn that the university no The six choices made by the vice presidents are longer planned to fill the position. -

Senate Action Looms on Mixed Tax Package TRENTON (AP) - Senate but Calling Himself an Ex- Shared in the Assembly

4> The Daily Register VOL.97 N0.118 SHREWSBURY, N. J. TUESDAY, DECEMBER 3, 1974 TEN CENTS Cleanup of extensive storm damage starts Monmouth County commu- Sea Bright was one of the Ave., about 100 feet away. the investment firm of Ed- nities were busy yesterday re- hardest hit towns on the Mon- Sea Bright also faced the wards & Hanly at 107 Broad pairing damage suffered dur mouth County coast Police same problem Monmouth St, while other businesses in ing the severe storm Sunday Chief John F Carmody said Beach encountered once the the heart of town suffered night and yesterday morning the North Beach area was ocean high tide subsided - similar experiences while shore towns today again "extremely bad " flooding from the Shrewsbury In Little Silver. Colonial face possible flood tides, Highway reopened Hiver on their western banks First National Bank had its which have hampered their Although tfis men reported Ocein Ave in Monmouth blinds hanging out of Us large recovery efforts for the past that Ocean Ave north of the Reach, was cleared yesterday broken windows, while two days. Rumson Bridge was reopened afternoon, said Sgt Joseph Medium Buick Opel on There may be some relief after high tide late last night, Masica. who also reported the Shrewsbury Ave., New for those low-lying areas the chief earlier said, "That borottgh'l fire department Shrewsbury, looked like it Weather forecasts indicate a part u( the road is very bad wrii called out in the height of was the target of a bomb. chance of some rain or wet Us covered with debris and llie storm at about 3am to Joe Middleton. -

Informationen Zu Bertolt Brecht

DREIGROSCHENHEFT INFORMATIONEN ZU BERTOLT BRECHT 24. JAHRGANG HEFT 2/2017 EINE NISCHE FÜR DAS BRECHTFESTIVAL IN AUGSBURG (FOTO) BRECHT-TAGE IN BERLIN, THEMA OKTOBERREVOLUTION DIETER HENNING ÜBER BRECHTS TROTZKI-LEKTÜRE SCHULWETTBEWERB DES BRECHTKREISES brechtige Bildbände aus dem Wißner-Verlag Seiten | über farbige Abbildungen ISBN ---- | , Seiten | über farbige Abbildungen ISBN ---- | , Mehr tolle Bildbände, spannende Erzählungen und weitere schöne Seiten von Augsburg nden Sie beim Wißner-Verlag unter www.wissner.com Bücher erhältlich im Buchhandel oder direkt beim Verlag. Anzeige_3GH_Jugendstil-Historismus_170228.indd 1 01.03.2017 15:06:08 INHALT Editorial 2 DER AUGSBURGER Impressum 2 Sonderausstellung im Augsburger Brechthaus (mf) 33 BRECHT-FESTIVAL AUGSBURG Zweiter Augsburger Schulwettbewerb des Die Maßnahme: Parteinahme gegen die Brechtkreises (mf) 34 „Partei“ 3 Mit Bi bei Kaffee und Kuchen 36 Andreas Hauff Eine Begegnung mit Frau Paula Gross, geb Banholzer 25 Jahre Brecht-Forschungsstätte 8 Wolfgang Leeb Michael Friedrichs Neuauflage: Die Erinnerungen von Paula Neunmalgut (mf) 10 Banholzer („Bi“) 38 Michael Friedrichs „Der gute Mensch von Downtown“ (mf) 11 Eine spannende Kombi: „Hollywooder MUSIK Liederbuch“ deutsch-afrikanisch (mf) 12 Bei Lotte Lenya zu Besuch 39 Werkstatttag Bertolt Brecht und Walter Ernst Scherzer Benjamin:Laboratorium Vielseitigkeit (mf) 13 Benjamin und Brecht heute begegnen 14 HEGEL Milena Massalongo Minima Hegeliana Zu Brechts Denkbildern (6) Das unheimliche Werk 40 BRECHT-TAGE BERLIN Frank Wagner Brecht-Tage -

Zeittafel Elektronische Edition

Zeittafel Elektronische Edition 1911-1916 1911 22. März Erster Theaterbesuch: SchillersWal - Mitte August Erster (erfolgloser) Publikations- lenstein im Augsburger Stadttheater (→ Erstes versuch: Gedicht Feiertag in der Münchener Theatererlebnis, in: Deutscher Theaterdienst 10 Zeitschrift Jugend (Brecht: Tagebuch № 10) [1928]; → BFA 21, 265) September Beginn der Bekanntschaft mit Oktober Gedicht Professor Sil Maria (Brecht: Caspar Neher (Högel 1973, 401) Tagebuch № 10); erste Hinweise auf Kenntnis Friedrich Nietzsches (→ NB 3, 16v.16-17r.4, 23r.18-24r.10, 46r-47v.8) 1913 10. Februar Geburtstagsgeschenk: Teile 3 bis 6 von 1914 Hebbel, Werke in zehn Teilen (Teile 7 und 8 am 4. Juni) (→ NB 3, 4r.12, 20r.1-4, 45v.18) Januar Das erste abgeschlossene Stück Die Bibel erscheint in der SchülerzeitschriftDie Ernte 15. Mai bis 25. Dezember Erstes erhalten geblie- benes Tagebuch (Brecht: Tagebuch № 10); darin 1. August Beginn des Ersten Weltkriegs früheste Belege der Bekanntschaft mit Heinrich 8. August Erste Zeitungspublikation: Augsburger Albrecht, Julius Bingen, Ernst Bohlig, Georg Kriegsbriefe (bis 28. September), Nr. 1: Turm- Eberle, Emil Enderlin, Fritz Gehweyer, Georg wacht in Augsburger Neueste Nachrichten Geyer, Walter Groos, Rudolf Hartmann, Hein- 24. August Erste Gedichtpublikationen: Der hei- rich Hofmann, Max Hohenester, Max Kern, lige Gewinn in Augsburger Neueste Nachrichten Wilhelm Kölbig, Georg Pfanzelt, Rudolf und und Dankgottesdienst in München-Augsburger Ludwig Prestel, Friedrich und Richard Reitter, Abendzeitung Heinrich Scheuffelhut, Joseph Schipfel, Max Schneider und Oskar Sternbacher (→ NB 1, 1r.3) 14. September Erste Rezension: Ein Volksbuch zu 19. Mai Erstes erhalten gebliebenes Gedicht Sommer Karl Lieblichs Gedichtsammlung Trautelse in (Brecht: Tagebuch № 10) Augsburger Neueste Nachrichten 27. und 29. Mai Erste Dramenprojekte Die Kinds- mörderin und Simson! (Brecht: Tagebuch № 10) Mai/Juni Erste bekannte Prosatexte Der Bin- 1915 gen. -

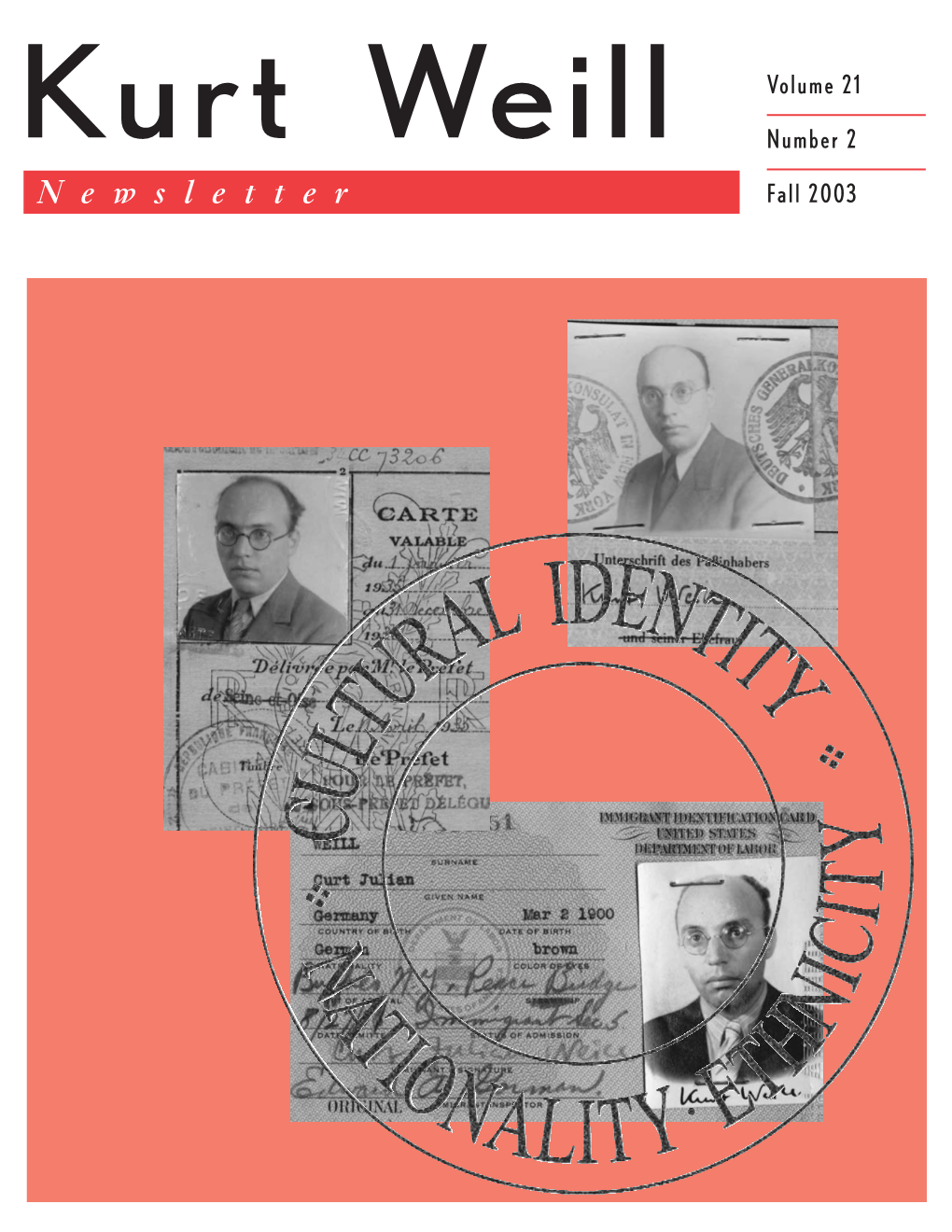

Kurt Weill Foundation

Introduction and Notes by David Drew Whether you care to mention Weill in the same breath prominently among the modern poets in a family library it is to have any kind of raison d'etre. The thoroughly as Hindemith or as Hollander, as Copland or as Cole where the works of Goethe and Heine, of Johann un-topical representation of our times which would result Porter; whether you see him as an outstanding German Gottfried von Herder and Moses Mendelssohn, had pride from such a change of direction must be supported by composer who somehow lost his voice when he settled of place, and where, no doubt, one could have found a strong conviction, whether it uses an earlier epoch in America, or as an outstanding Broadway composer some of the writings of Eduard Bernstein , if not of (the to mirror aspects of present-day life or whether it finds who somehow contrived to write a hit-show called " The young?) Marx, and perhaps even a crumpled copy of a unique, definitive and timeless form for present-day Threepenny Opera" during his otherwise obscure and the Erfurt Programme of 1891 . phenomena. The absence of inner and outer complica probably misspent Berlin youth ; whether you disagree Unlike Brecht, Weill never needed to repudiate his early tions (in the material and in the means of expression) with both these views and either find evidence of a strik- backg round in order to define his artistic functions and is in keeping with the more naive disposition of the ingly original mind at all stages in his career (but at some objectives. -

Zum Download Des Heftes Bitte Anklicken

DREIGROSCHENHEFT INFORMATIONEN ZU BERTOLT BRECHT 23. JAHRGANG HEFT 4/2016 BRECHT-KARIKATUREN AUS DEM „SIMPLIZISSIMUS“ (ZEICHNUNG) KLAUS-DIETER KRABIEL ÜBER EIN CAROLA-NEHER-GEDICHT BRECHT AUF DEN BÜHNEN IN DER NEUEN SPIELZEIT BERICHTE VON DER IBS-TAGUNG IN OXFORD fantasievoll &farbenfroh Es war einmal ein Rabe … Kinder illustrieren Brecht ISBN ---- | Seiten | , BRECHT FÜR GROSS UND KLEIN WISSENSWERT & AUFSCHLUSSREICH Und dort im Lichte steht Bert Brecht. Rein. Sachlich. Böse. Die Schätze der Brechtsammlung der Staats- und Stadtbibliothek Augsburg ISBN ---- | Seiten | , Zum Brechtfestival hat die Stadt Augsburg ein Buch mit den schönsten Werken aus einem Mal- und Zeichenwettbewerb sowie den Katalog zur Ausstellung in der Stadtsparkasse mit Abbildungen von Originaldokumenten (Auszüge privater Korrespondenz, Zeitungsausschnitte …) herausgegeben. Erhältlich im Buchhandel oder direkt beim Wißner-Verlag – auch im Internet: www.wissner.com Anzeige_3GH_Brecht_141113.indd 1 13.11.2014 12:51:57 INHALT fantasievoll &farbenfroh Es war einmal ein Rabe … Kinder illustrieren Brecht Editorial 2 BRECHT INTERNATIONAL ISBN ---- | Seiten | , Impressum 2 Dilemma des guten Menschen auf der chinesischen Xiqu-Bühne: Die Yueju-Oper LYRIK „Der gute Mensch von Jiangnan“ 28 Brechts „Rat an die Schauspielerin C N “ 3 Lin Chen Zur Entstehungs- und Textgeschichte eines Gedichts Neu gehört: Salzkammergut-Festwochen Klaus-Dieter Krabiel boten dem Stückeschreiber ein Forum 31 Ernst Scherzer DER AUGSBURGER REZENSION Die Legende von Bertolt Brechts Landhaus in Utting