Weill and His Collaborators Volume 15 in This Issue Kurt Weill Number 1 Newsletter Spring 1997

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

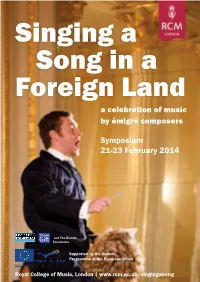

Symposium Programme

Singing a Song in a Foreign Land a celebration of music by émigré composers Symposium 21-23 February 2014 and The Eranda Foundation Supported by the Culture Programme of the European Union Royal College of Music, London | www.rcm.ac.uk/singingasong Follow the project on the RCM website: www.rcm.ac.uk/singingasong Singing a Song in a Foreign Land: Symposium Schedule FRIDAY 21 FEBRUARY 10.00am Welcome by Colin Lawson, RCM Director Introduction by Norbert Meyn, project curator & Volker Ahmels, coordinator of the EU funded ESTHER project 10.30-11.30am Session 1. Chair: Norbert Meyn (RCM) Singing a Song in a Foreign Land: The cultural impact on Britain of the “Hitler Émigrés” Daniel Snowman (Institute of Historical Research, University of London) 11.30am Tea & Coffee 12.00-1.30pm Session 2. Chair: Amanda Glauert (RCM) From somebody to nobody overnight – Berthold Goldschmidt’s battle for recognition Bernard Keeffe The Shock of Exile: Hans Keller – the re-making of a Viennese musician Alison Garnham (King’s College, London) Keeping Memories Alive: The story of Anita Lasker-Wallfisch and Peter Wallfisch Volker Ahmels (Festival Verfemte Musik Schwerin) talks to Anita Lasker-Wallfisch 1.30pm Lunch 2.30-4.00pm Session 3. Chair: Daniel Snowman Xenophobia and protectionism: attitudes to the arrival of Austro-German refugee musicians in the UK during the 1930s Erik Levi (Royal Holloway) Elena Gerhardt (1883-1961) – the extraordinary emigration of the Lieder-singer from Leipzig Jutta Raab Hansen “Productive as I never was before”: Robert Kahn in England Steffen Fahl 4.00pm Tea & Coffee 4.30-5.30pm Session 4. -

A Foreign Affair (1948)

Chapter 3 IN THE RUINS OF BERLIN: A FOREIGN AFFAIR (1948) “We wondered where we should go now that the war was over. None of us—I mean the émigrés—really knew where we stood. Should we go home? Where was home?” —Billy Wilder1 Sightseeing in Berlin Early into A Foreign Affair, the delegates of the US Congress in Berlin on a fact-fi nding mission are treated to a tour of the city by Colonel Plummer (Millard Mitchell). In an open sedan, the Colonel takes them by landmarks such as the Brandenburg Gate, the Reichstag, Pariser Platz, Unter den Lin- den, and the Tiergarten. While documentary footage of heavily damaged buildings rolls by in rear-projection, the Colonel explains to the visitors— and the viewers—what they are seeing, combining brief factual accounts with his own ironic commentary about the ruins. Thus, a pile of rubble is identifi ed as the Adlon Hotel, “just after the 8th Air Force checked in for the weekend, “ while the Reich’s Chancellery is labeled Hitler’s “duplex.” “As it turned out,” Plummer explains, “one part got to be a great big pad- ded cell, and the other a mortuary. Underneath it is a concrete basement. That’s where he married Eva Braun and that’s where they killed them- selves. A lot of people say it was the perfect honeymoon. And there’s the balcony where he promised that his Reich would last a thousand years— that’s the one that broke the bookies’ hearts.” On a narrative level, the sequence is marked by factual snippets infused with the snide remarks of victorious Army personnel, making the fi lm waver between an educational program, an overwrought history lesson, and a comedy of very dark humor. -

31 Days of Oscar® 2010 Schedule

31 DAYS OF OSCAR® 2010 SCHEDULE Monday, February 1 6:00 AM Only When I Laugh (’81) (Kevin Bacon, James Coco) 8:15 AM Man of La Mancha (’72) (James Coco, Harry Andrews) 10:30 AM 55 Days at Peking (’63) (Harry Andrews, Flora Robson) 1:30 PM Saratoga Trunk (’45) (Flora Robson, Jerry Austin) 4:00 PM The Adventures of Don Juan (’48) (Jerry Austin, Viveca Lindfors) 6:00 PM The Way We Were (’73) (Viveca Lindfors, Barbra Streisand) 8:00 PM Funny Girl (’68) (Barbra Streisand, Omar Sharif) 11:00 PM Lawrence of Arabia (’62) (Omar Sharif, Peter O’Toole) 3:00 AM Becket (’64) (Peter O’Toole, Martita Hunt) 5:30 AM Great Expectations (’46) (Martita Hunt, John Mills) Tuesday, February 2 7:30 AM Tunes of Glory (’60) (John Mills, John Fraser) 9:30 AM The Dam Busters (’55) (John Fraser, Laurence Naismith) 11:30 AM Mogambo (’53) (Laurence Naismith, Clark Gable) 1:30 PM Test Pilot (’38) (Clark Gable, Mary Howard) 3:30 PM Billy the Kid (’41) (Mary Howard, Henry O’Neill) 5:15 PM Mr. Dodd Takes the Air (’37) (Henry O’Neill, Frank McHugh) 6:45 PM One Way Passage (’32) (Frank McHugh, William Powell) 8:00 PM The Thin Man (’34) (William Powell, Myrna Loy) 10:00 PM The Best Years of Our Lives (’46) (Myrna Loy, Fredric March) 1:00 AM Inherit the Wind (’60) (Fredric March, Noah Beery, Jr.) 3:15 AM Sergeant York (’41) (Noah Beery, Jr., Walter Brennan) 5:30 AM These Three (’36) (Walter Brennan, Marcia Mae Jones) Wednesday, February 3 7:15 AM The Champ (’31) (Marcia Mae Jones, Walter Beery) 8:45 AM Viva Villa! (’34) (Walter Beery, Donald Cook) 10:45 AM The Pubic Enemy -

Volume 18 No. 2, Spring 2019

OPERALEX.ORGbravo lexSPRING 2019! inside ALL IN THE FAMILY UKOT grads, and their daughter, thrive in NYC Page 2 OH, THE PLACES THEY GO! Students and graduates cross the continent and the sea to share their talents Page 3 Grand Time! Why Baldwin keeps coming back “Returning to Lexington is always a highlight of my year.” Grand Night For 19 years Dr. Robert Baldwin, formerly of UK and for Singing now Director of Orchestras and of Graduate Studies at Where: Singletary Center for the Arts, the University of Utah, and Music Director of the Salt Now you can support UK campus Lake Symphony, has enthusiastically returned to lead us when you shop When: June 7, at Amazon! Check the orchestra in A Grand Night for Singing. I recently 8,14,15 at 7:30 out operalex.org asked him what makes it such a highlight. p.m. “Make no mistake, this is a professional quality pro- June 9,16 at 2 p.m. duction. Many of Lexington’s most talented perform- Tickets: Call FOLLOW UKOT ers are involved with Grand Night. It is indicative of 859.257.4929 or visit the depth of talent we have here. I would not hesitate on social media! www.SCFATickets. lFacebook: UKOperaTheatre to compare this show to most professional traveling com lTwitter: UKOperaTheatre Broadway shows. Talent is only one element, however. lInstagram: ukoperatheatre See Page 5 Page 2 Andrea Jones-Sojola and Phumzile (“Puma”) Sojola, UKOT graduates, are both classically trained singers with strong back- grounds in opera, musical theater and spirituals. In 2012 they both made their Broadway debuts in the Tony Award-winning production UK of Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess, and in June 2014 they joined inter- national stars in a concert in Carnegie Hall’s popular series Musical Explorers. -

Chapters 1-10 Notes

Notes and Sources Chapter 1 1. Carol Steinbeck - see Dramatis Personae. 2. Little Bit of Sweden on Sunset Boulevard - the restaurant where Gwyn and John went on their first date. 3. Black Marigolds - a thousand year’s old love poem (in translation) written by Kasmiri poet Bilhana Kavi. 4. Robert Louis Stevenson - Scottish novelist, most famous for Treasure Island, Kidnapped and The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. Stevenson met with one of the Wagner family on his travels. He died aged 44 in Samoa. 5. Synge – probably the Irish poet and playwright. 6. Matt Dennis - band leader, pianist and musical arranger, who wrote the music for Let’s Get Away From It All, recorded by Frank Sinatra, and others. 7. Dr Paul de Kruif - an American micro-biologist and author who helped American writer Sinclair Lewis with the novel Arrowsmith, which won a Pulitzer Prize. 8. Ed Ricketts - see Dramatis Personae. 9. The San Francisco State Fair - this was the Golden Gate International Exposition of 1939 and 1940, held to celebrate the city’s two newly built bridges – The San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge and The Golden Gate Bridge. It ran from February to October 1939, and part of 1940. At the State Fair, early experiments were being made with television and radio; Steinbeck heard Gwyn singing on the radio and called her, some months after their initial meeting. Chapter 2 1. Forgotten Village - a screenplay written by John Steinbeck and released in 1941. Narrated by Burgess Meredith - see Dramatis Personae. The New York authorities banned it, due to the portrayal of childbirth and breast feeding. -

Kleinkunststucke

KLEINKUNSTSTUCKE Band 2 Hoppla, wir beben Kabarett einer gewissen Republik 1918-1933 Herausgegeben von Volker Kühn VORWORT 13 DADA-PROLOG Aufbruch ins Ungewisse 15 Kurt Schwitters: Undumm 20 Richard Huelsenbeck: Dada-Rede 20 Walter Mehring: Der Coitus im Dreimäderlhaus 21 Kurt Schwitters: An Anna Blume 23 Richard Huelsenbeck: Dada-Schalmei 24 Walter Mehring: Wettrennen zwischen Nähmaschine und Schreibmaschine 25 Walter Mehring: Dada-Prolog 1919 25 Wieland Herzfelde: Trauerdiriflog 27 George Grosz: Gesang 28 REVOLUTION! - REWOLUTSCHION?? Eine junge Republik retabliert sich 29 Karl Kraus: Umsturz 34 Hans Janowitz: Ein verhurtes Kind singt 34 Klabund: Berliner Weihnacht 1918 35 Walter Mehring: Deutscher Liebesfrühling 1919 36 Klabund: Deutsches Volkslied 37 Erich Weinert: Einheitsvolkslied 38 Richard Huelsenbeck: Schieber-Politik 39 Erich Mühsam: Gesang der Intellektuellen 39 Weiß Ferdl: Gleichheitshymne 41 Weiß Ferdl: Revoluzzerlied 41 Kurt Tucholsky: Einkäufe 1919 42 Walter Mehring: Kasinolied 43 Kurt Tucholsky: Revolutions-Rückblick 45 Anonym: Wilhelm ohne Krone 46 EINFACH KLASSISCH! Auf ein neues - Schall und Rauch 47 Walter Mehring: Anleitung für Kabarettbesucher 52 Kurt Tucholsky: Wenn der alte Motor wieder tackt,., 53 Kurt Tucholsky: Die blonde Dame singt 56 Walter Mehring: 2 Arien (einfach klassisch!) 57 Klabund: Die Wirtschafterin 59 Klabund: Rag 1920 59 Klabund: Matrosenlied 61 Klabund: Die Harfenjule 62 Hans Heinrich v. Twardowski: Neue Galgenlieder 63 Munkepunke: Excentriks 63 Max Herrmann-Neiße: Die Pastorstochter 64 Joachim Ringelnatz: Vom Seemann Kuttel Daddeldu 65 Joachim Ringelnatz: Klimmzug 67 Kurt Tucholsky: Der Zigaretten-Fritze 68 Friedrich Hollaender: Tritt mir bloß nich auf die Schuh 74 Klabund: Hamburger Hurenlied 75 Kurt Tucholsky: Adagio con brio 76 HEIMAT BERLIN Von Haiensee bis Jottweedeh: Licht & Schatten 77 Walter Mehring: Berlin simultan 82 K. -

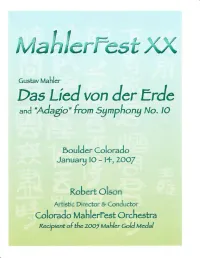

Program Book

I e lson rti ic ire r & ndu r Schedule of Events CHAMBER CONCERTS Wednesday, January 1.O, 2007, 7100 PM Boulder Public Library Canyon Theater,9th & Canyon Friday, January L3, 7 3O PM Rocky Mountain Center for Musical Arts, 200 E. Baseline Rd., Lafayette Program: Songs on Chinese andJapanese Poems SYMPOSIUM Saturday, January L7, 2OO7 ATLAS Room 100, University of Colorado-Boulder 9:00 AM - 4:30 PM 9:00 AM: Robert Olson, MahlerFest Conductor & Artistic Director 10:00 AM: Evelyn Nikkels, Dutch Mahler Society 11:00 AMrJason Starr, Filmmaker, New York City Lunch 1:00 PM: Stephen E Heffiing, Case Western Reserve University, Keynote Speaker 2100 PM: Marilyn McCoy, Newburyport, MS 3:00 PMr Steven Bruns, University of Colorado-Boulder 4:00 PM: Chris Mohr, Denver, Colorado SYMPHONY CONCERTS Saturday, January L3' 2007 Sunday,Janaary L4,2O07 Macky Auditorium, CU Campus, Boulder Thomas Hampson, baritone Jon Garrison, tenor The Colorado MahlerFest Orchestra, Robert Olson, conductor See page 2 for details. Fundingfor MablerFest XXbas been Ttrouid'ed in ltartby grantsftom: The Boulder Arts Commission, an agency of the Boulder City Council The Scienrific and Culrural Facilities Discrict, Tier III, administered by the Boulder County Commissioners The Dietrich Foundation of Philadelphia The Boulder Library Foundation rh e va n u n dati o n "# I:I,:r# and many music lovers from the Boulder area and also from many states and countries [)AII-..]' CAMEI{\ il M ULIEN The ACADEMY Twent! Years and Still Going Strong It is almost impossible to fully comprehend -

You Can Choose to Be Happy

You Can Choose To Be Happy: “Rise Above” Anxiety, Anger, and Depression with Research Evidence Tom G. Stevens PhD Wheeler-Sutton Publishing Co. YOU CAN CHOOSE TO BE HAPPY: “Rise Above” Anxiety, Anger, and Depression With Research Evidence Tom G. Stevens PhD Wheeler-Sutton Publishing Co. Palm Desert, California 92260 Revised (Second) Edition, 2010 First Edition, 1998; Printings, 2000, 2002. Copyright © 2010 by Tom G. Stevens PhD. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews; or except as provided by U. S. copyright law. For more information address Wheeler-Sutton Publishing Co. The cases mentioned herein are real, but key details were changed to protect identity. This book provides general information about complex issues and is not a substitute for professional help. Anyone needing help for serious problems should see a qualified professional. Printed on acid-free paper. Publisher’s Cataloging-in-Publication Data Stevens, Tom G., Ph.D. 1942- You can choose to be happy: rise above anxiety, anger, and depression./ Tom G. Stevens Ph.D. –2nd ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-0-9653377-2-4 1. Happiness. 2. Self-actualization (Psychology) I. Title. BF575.H27 S84 2010 (pbk.) 158-dc22 Library of Congress Control Number: 2009943621 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION: ..................................................................................................................... -

Performing Music History Edited by John C

musicians speak first-hand about music history and performance performing music history edited by john c. tibbetts michael saffle william a. everett Performing Music History John C. Tibbetts · Michael Saffe William A. Everett Performing Music History Musicians Speak First-Hand about Music History and Performance Forewords by Emanuel Ax and Lawrence Kramer John C. Tibbetts William A. Everett Department of Film and Media Studies Conservatory of Music and Dance University of Kansas University of Missouri-Kansas City Lawrence, KS, USA Kansas City, MO, USA Michael Saffe Department of Religion and Culture Virginia Tech Blacksburg, VA, USA ISBN 978-3-319-92470-0 ISBN 978-3-319-92471-7 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-92471-7 Library of Congress Control Number: 2018951048 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2018 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifcally the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microflms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specifc statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. -

5. Calling for International Solidarity: Hanns Eisler’S Mass Songs in the Soviet Union

From Massenlieder to Massovaia Pesnia: Musical Exchanges between Communists and Socialists of Weimar Germany and the Early Soviet Union by Yana Alexandrovna Lowry Department of Music Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Bryan Gilliam, Supervisor ___________________________ Edna Andrews ___________________________ John Supko ___________________________ Jacqueline Waeber Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music in the Graduate School of Duke University 2014 i v ABSTRACT From Massenlieder to Massovaia Pesnia: Musical Exchanges between Communists and Socialists of Weimar Germany and the Early Soviet Union by Yana Alexandrovna Lowry Department of Music Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Bryan Gilliam, Supervisor ___________________________ Edna Andrews ___________________________ John Supko ___________________________ Jacqueline Waeber An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music in the Graduate School of Duke University 2014 Copyright by Yana Alexandrovna Lowry 2014 Abstract Group songs with direct political messages rose to enormous popularity during the interwar period (1918-1939), particularly in recently-defeated Germany and in the newly- established Soviet Union. This dissertation explores the musical relationship between these two troubled countries and aims to explain the similarities and differences in their approaches to collective singing. The discussion of the very complex and problematic relationship between the German left and the Soviet government sets the framework for the analysis of music. Beginning in late 1920s, as a result of Stalin’s abandonment of the international revolutionary cause, the divergences between the policies of the Soviet government and utopian aims of the German communist party can be traced in the musical propaganda of both countries. -

Wiederentdeckt. Der Komponist Berthold Goldschmidt

BERTHOLD GOLDSCHMIDT Geflohen - verstummt - wiederentdeckt. Der Komponist Berthold Goldschmidt GESPRÄCHSKONZERT DER REIHE MUSICA REANIMATA AM 22. NOVEMBER 2016 IN BERLIN BESTANDSVERZEICHNIS DER MEDIEN VON UND ÜBER BERTHOLD GOLDSCHMIDT IN DER ZENTRAL- UND LANDESBIBLIOTHEK BERLIN INHALTSANGABE KOMPOSITIONEN VON BERTHOLD GOLDSCHMIDT Noten Seite 3 Aufnahmen auf CD Seite 4 Aufnahmen in der Naxos Music Library Seite 6 SEKUNDÄRLITERATUR ÜBER BERTHOLD GOLDSCHMIDT Seite 7 LEGENDE Freihand Bestand im Lesesaal frei zugänglich Magazin Bestand für Leser nicht frei zugänglich, Bestellung möglich Außenmagazin Bestand außerhalb der Häuser, Bestellung möglich AGB Amerika-Gedenkbibliothek, Blücherplatz 1, 10961 Berlin – Kreuzberg Berlin-Studien im Haus BStB (Berliner Stadtbibliothek) BStB Berliner Stadtbibliothek, Breite Str. 30-36, 10178 Berlin – Mitte Naxos Music Library Streamingportal mit klassischer Musik –- sowohl an den Datenbank-PCs der ZLB als auch (mit Bibliotheksausweis) von zu Hause nutzbar 2 KOMPOSITIONEN VON BERTHOLD GOLDSCHMIDT NOTEN Mediterranean songs : for tenor and orchestra = Gesänge vom Mittelmeer / Berthold Goldschmidt. - London : Boosey & Hawkes, c 1996. - 83 Seiten. HPS 1294 Exemplare: Standort Außenmagazin AGB Signatur 008/000 009 519 (No 139 Golds 1) Passacaglia opus 4 for large orchestra / Berthold Goldschmidt. - London : Boosey & Hawkes, 1998. - 1 Studienpartitur (22 Seiten). - ISMN M-060-10791-7 Exemplare: Standort Magazin AGB Signatur 108/000 052 355 (No 147 Golds 1) String quartet no 2 : for string quartet [Noten] / Berthold Goldschmidt. - London : Boosey & Hawkes, [1991]. - 1 Partitur (42 Seiten) ; 31 cm. - Anmerkungen des Komponisten in Deutsch und Englisch Exemplare: Standort Freihand AGB Signatur No 190 Golds 2 String quartet no. 4 (1992) / Berthold Goldschmidt. - London [u.a.] : Boosey & Hawkes, 1994. - 20 Seiten Exemplare: Standort Magazin AGB Signatur No 190 Golds 1 [Sinfonien, Nr. -

Traum Und Abgrund Das Leben Der Schauspielerin Carola Neher Von Marianne Thoms

SWR2 MANUSKRIPT ESSAYS FEATURES KOMMENTARE VORTRÄGE SWR2 Wissen Traum und Abgrund Das Leben der Schauspielerin Carola Neher Von Marianne Thoms Carola Neher, eine Lieblingsschauspielerin Bert Brechts, flieht vor den Nazis nach Moskau, gerät in stalinistischen Terror und stirbt, nach fünf Jahren Lagerhaft, entkräftet an Typhus. Sendung: Freitag, 28. September 2012, 8.30 – 8.58 Uhr Wiederholung, Donnerstag, 02.08.2018 Redaktion: Udo Zindel Regie: Andrea Leclerque Produktion: SWR 2012 Bitte beachten Sie: Das Manuskript ist ausschließlich zum persönlichen, privaten Gebrauch bestimmt. Jede weitere Vervielfältigung und Verbreitung bedarf der ausdrücklichen Genehmigung des Urhebers bzw. des SWR. MANUSKRIPT Regie: Musikblende Klaviermusik Chopin, darüber sprechen: Carola: Man nehme eine beliebige schöne Frau und lasse sie über die Bühne gehen. Sie wird über ihre eigenen Beine und Gedanken stolpern. Sie ist aus ihrem Element gekommen, ein Fisch auf dem Land. Aber wir Schauspielerinnen sind erst auf der Bühne in unserem Element – wir stolpern nur im Leben. Ansager.: Traum und Abgrund – Das Leben der Schauspielerin Carola Neher, 1900 bis 1942. Eine Sendung von Marianne Thoms. Sprecherin: 1 Die gebürtige Münchnerin ist schön, intelligent und hochbegabt. Schon als Kind träumt sich Carola Neher in die Welt des Theaters. Niemand kann sie aufhalten – weder ihr herrschsüchtiger Vater, ein Musiker, noch die besorgte Mutter, eine Gastwirtin. Ihr Bruder Josef sagt über sie: Zitator: Die wäre in jedem Fall Schauspielerin geworden. Und wenn sie im nächsten Jahr daran gestorben wäre. Sprecherin: Mit hemmungslos vitaler Darstellungslust erobert Carola Neher ab ihrem 20. Lebensjahr Bühne für Bühne: Baden-Baden, Nürnberg, München, Breslau – immer zielstrebig mit dem Blick auf Berlin. Mit frechem Vergnügen nutzt sie auch ihre Anziehungskraft auf Männer.