Kurt Weill Foundation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Children in Opera

Children in Opera Children in Opera By Andrew Sutherland Children in Opera By Andrew Sutherland This book first published 2021 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2021 by Andrew Sutherland Front cover: ©Scott Armstrong, Perth, Western Australia All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-6166-6 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-6166-3 In memory of Adrian Maydwell (1993-2019), the first Itys. CONTENTS List of Figures........................................................................................... xii Acknowledgements ................................................................................. xxi Chapter 1 .................................................................................................... 1 Introduction What is a child? ..................................................................................... 4 Vocal development in children ............................................................. 5 Opera sacra ........................................................................................... 6 Boys will be girls ................................................................................. -

Document .Pdf

CNDP-CRDP n° 135 octobre 2011 Les dossiers pédagogiques « Théâtre » et « Arts du cirque » du réseau SCÉRÉN en partenariat avec le CDN de Sartrouville et des Yvelines. Une collection coordonnée par le CRDP de l’académie de Paris. L’Opéra de quat’sous Avant de voir le spectacle : la représentation en appétit ! Distanciation brechtienne et théâtre épique [page 5] Vers un renouveau du genre lyrique : l’opéra épique de Kurt Weill [page 6] de Bertolt Brecht, L’Opéra de quat’sous : musique Kurt Weill, les origines [page 7] mise en scène Laurent Frechuret, Fable et personnages direction musicale Samuel Jean [page 11] Accueil et postérité de l’œuvre Du 4 au 21 octobre 2011 au CDN de Sartrouville et des Yvelines © JEAN-MArc LobbÉ / PHOTO DE RÉPÉTITION [page 14] Rebonds et résonances [page 15] Édito Après la représentation : Plus de quatre-vingts ans après la première de L’Opéra de quat’sous, l’œuvre a-t-elle pistes de travail perdu de sa modernité, de son acuité ? « Non », répondent en chœur tous les metteurs en scène qui, de par le monde, plébiscitent cet « opéra », devenu une des œuvres les Juste avant le spectacle : plus populaires du répertoire. Et effectivement, entre l’Angleterre de 1728, l’Allemagne l’affiche [page 16] à la veille de la crise de 1929 et le contexte actuel, marqué par la crise économique, la remise en cause du pouvoir de l’argent et le questionnement sur l’homme, que D’un quat’sous à l’autre d’échos ! C’est la même « danse au bord du volcan – à quatre pas de la descente aux [page 17] enfers 1 » ! Après Laurent Pelly à la Comédie-Française, Laurent Fréchuret, directeur Les partis pris du CDN de Sartrouville et des Yvelines, s’empare de ce matériau pour son ouverture de Laurent Fréchuret, de saison. -

![Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8862/archons-commanders-notice-they-are-not-anlien-parasites-and-then-in-a-mirror-image-of-the-great-emanations-of-the-pleroma-hundreds-of-lesser-angels-438862.webp)

Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels

A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES WATCH THIS IMPORTANT VIDEO UFOs, Aliens, and the Question of Contact MUST-SEE THE OCCULT REASON FOR PSYCHOPATHY Organic Portals: Aliens and Psychopaths KNOWLEDGE THROUGH GNOSIS Boris Mouravieff - GNOSIS IN THE BEGINNING ...1 The Gnostic core belief was a strong dualism: that the world of matter was deadening and inferior to a remote nonphysical home, to which an interior divine spark in most humans aspired to return after death. This led them to an absorption with the Jewish creation myths in Genesis, which they obsessively reinterpreted to formulate allegorical explanations of how humans ended up trapped in the world of matter. The basic Gnostic story, which varied in details from teacher to teacher, was this: In the beginning there was an unknowable, immaterial, and invisible God, sometimes called the Father of All and sometimes by other names. “He” was neither male nor female, and was composed of an implicitly finite amount of a living nonphysical substance. Surrounding this God was a great empty region called the Pleroma (the fullness). Beyond the Pleroma lay empty space. The God acted to fill the Pleroma through a series of emanations, a squeezing off of small portions of his/its nonphysical energetic divine material. In most accounts there are thirty emanations in fifteen complementary pairs, each getting slightly less of the divine material and therefore being slightly weaker. The emanations are called Aeons (eternities) and are mostly named personifications in Greek of abstract ideas. -

Don Juan Entire First Folio

First Folio Teacher Curriculum Guide Don Juan by Molière translated, adapted and directed by Stephen Wadsworth January 24—March 19, 2006 First Folio Teacher Curriculum Guide Table of Contents Page Number Welcome to the Shakespeare Theatre Company’s production ofDon Juan by Molière! A Brief History of the Audience…………………….1 Each season, the Shakespeare Theatre Company About the Playwright presents five plays by William Shakespeare and other classic playwrights. The Education Department Molière’s Life………………….…………………………………3 continues to work to deepen understanding, Molière’s Theatre…….……………………………………….4 appreciation and connection to classic theatre in 17th•Century France……………………………………….6 learners of all ages. One approach is the publication of First Folio: Teacher Curriculum Guides. About the Play Synopsis of Don Juan…………………...………………..8 In the 2005•06 season, the Education Department Don Juan Timeline….……………………..…………..…..9 will publish First Folio: Teacher Curriculum Guides for Marriage & Family in 17th•Century our productions ofOthello, The Comedy of Errors, France…………………………………………………...10 Don Juan, The Persiansand Love’s Labor’s Lost. The Guides provide information and activities to help Splendid Defiance……………………….....................11 students form a personal connection to the play before attending the production at the Shakespeare Classroom Connections Theatre Company. First Folio guides are full of • Before the Performance……………………………13 material about the playwrights, their world and the Translation & Adaptation plays they penned. Also included are approaches to Censorship explore the plays and productions in the classroom Questioning Social Mores before and after the performance.First Folio is Playing Around on Your Girlfriend/ designed as a resource both for teachers and Boyfriend students. Commedia in Molière’s Plays The Shakespeare Theatre Company’s Education Department provides an array of School, • After the Performance………………………………14 Community, Training and Audience Enrichment Friends Don’t Let Friends.. -

AURUS — Classic Analogue Feel with the Power of a Digital Console!

22 directly accessible parameters — 11 dual concentric encoders per channel strip • ready for 96 kHz • parallel mixdown to multiple multichannel formats • fully integrated into the NEXUS STAR routing system AURUS — Classic analogue feel with the power of a digital console! AURUS the Direct-Access Console The novel digital mixing-console architecture introduced by the The unusually large number of controls (at least for a digital young and innovative Stage Tec team in 1994 has since signifi cantly con sole) provide instant access to the desired audio channels. infl uenced the design of current digital desks and not only in ap pear- De pending on the confi guration, up to 96 channel strips and 300 ance. And CANTUS — their fi rst digital console — became a huge au dio channels are available. Optimum access to all controls and success. per fect legibility of all displays and indicators offers a high degree In 2002, Stage Tec introduced a new fi rst-class mixing console of user-friendliness whilst keeping the training period short. developed from scratch: AURUS — the Direct-Access Console. Many users have since evaluated the console, opted for it, and given AURUS as a desktop version or with easily removable legs is feedback and made suggestions for optimisations. Thus, the AURUS the perfect tour companion. Thanks to its compact size and low is now available incorporating generic software functions for broad- weight, AURUS guarantees ultra-short set-up times, saving time and cast ing, sound reinforcement, theatres, and recording. money. AURUS continues the original concept of consistent sep a ra tion These characteristics as well as the hot-swap capabilities of all of con sole and I/O matrix, which allows for setting up distributed hard ware elements, full redundancy up to double optical lines, low and effi cient audio networks; but at the same time, this sep a ra tion power consumption, and thus low heat dissipation make AURUS is supple mented by a unique control concept, instant access to all highly suitable for OB truck installation, as well. -

Die Dreigroschenoper Kurt Weill (1900-1950) Hauptmann (1897-1973), Bertolt Brecht (1898-1956)

1/14 Data Livret de : Elisabeth Die Dreigroschenoper Kurt Weill (1900-1950) Hauptmann (1897-1973), Bertolt Brecht (1898-1956) Langue : Allemand Genre ou forme de l’œuvre : Œuvres musicales Date : 1928 Note : Pièce avec musique en 3 actes. - Livret de Bertolt Brecht et Elisabeth Hauptmann, d'après "The beggar's opera" de John Gay. - 1re exécution : Berlin, Theater am Schiffbauerdamm, le 31 août 1928, avec Lotte Lenya (soprano) Le compositeur en a tiré une suite pour instruments à vent intitulée "Kleine Dreigroschenmusik" Domaines : Musique Autres formes du titre : L'opéra de quat'sous (français) The threepenny opera (anglais) Détails du contenu (4 ressources dans data.bnf.fr) Contient (2) Die Dreigroschenoper. 1. , Kurt Weill (1900-1950) Die Dreigroschenoper. Die , Kurt Weill (1900-1950) Aufzug. Barbara Song Moritat von Mackie Messer (1928) (1928) Voir aussi (1) Die Dreigroschenoper : film , Georg Wilhelm Pabst (1931) (1885-1967) data.bnf.fr 2/14 Data Voir l'œuvre musicale (1) Kleine Dreigroschenmusik , Kurt Weill (1900-1950) (1928) Éditions de Die Dreigroschenoper (175 ressources dans data.bnf.fr) Enregistrements (136) DIE DREIGROSCHENOPER = , Kurt Weill (1900-1950), extrait : DE L'OPERA DE , Kurt Weill (1900-1950), L'Opéra de Quat' sous S.l. : s.n. , s.d. QUAT'SOUS A SEPTEMBER S.l. : s.n. , s.d. SONG extrait : GUITARE PARTY , C. Gray, D. Bennett, Ted choix : Chanson pour le , Mertens, J. Paris, J. Snyder [et autre(s)], S.l. : théâtre Sundstrom [et autre(s)], S.l. s.n. , s.d. : s.n. , s.d. extrait : LES GRANDES , Kurt Weill (1900-1950), extrait : JULIETTE GRECO : , Kurt Weill (1900-1950), CHANSONS DE JULIETTE Hubert Giraud (1920-2016), JE SUIS COMME JE SUIS Stéphane Golmann GRECO René-Louis Lafforgue (1921-1987), Jacques (1928-1967) [et autre(s)], Prévert (1900-1977) [et S.l. -

5. Calling for International Solidarity: Hanns Eisler’S Mass Songs in the Soviet Union

From Massenlieder to Massovaia Pesnia: Musical Exchanges between Communists and Socialists of Weimar Germany and the Early Soviet Union by Yana Alexandrovna Lowry Department of Music Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Bryan Gilliam, Supervisor ___________________________ Edna Andrews ___________________________ John Supko ___________________________ Jacqueline Waeber Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music in the Graduate School of Duke University 2014 i v ABSTRACT From Massenlieder to Massovaia Pesnia: Musical Exchanges between Communists and Socialists of Weimar Germany and the Early Soviet Union by Yana Alexandrovna Lowry Department of Music Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Bryan Gilliam, Supervisor ___________________________ Edna Andrews ___________________________ John Supko ___________________________ Jacqueline Waeber An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music in the Graduate School of Duke University 2014 Copyright by Yana Alexandrovna Lowry 2014 Abstract Group songs with direct political messages rose to enormous popularity during the interwar period (1918-1939), particularly in recently-defeated Germany and in the newly- established Soviet Union. This dissertation explores the musical relationship between these two troubled countries and aims to explain the similarities and differences in their approaches to collective singing. The discussion of the very complex and problematic relationship between the German left and the Soviet government sets the framework for the analysis of music. Beginning in late 1920s, as a result of Stalin’s abandonment of the international revolutionary cause, the divergences between the policies of the Soviet government and utopian aims of the German communist party can be traced in the musical propaganda of both countries. -

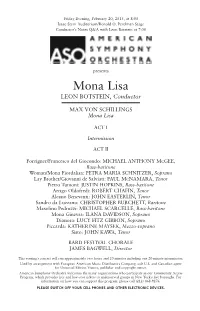

Mona Lisa LEON BOTSTEIN, Conductor

Friday Evening, February 20, 2015, at 8:00 Isaac Stern Auditorium/Ronald O. Perelman Stage Conductor’s Notes Q&A with Leon Botstein at 7:00 presents Mona Lisa LEON BOTSTEIN, Conductor MAX VON SCHILLINGS Mona Lisa ACT I Intermission ACT II Foreigner/Francesco del Giocondo: MICHAEL ANTHONY MCGEE, Bass-baritone Woman/Mona Fiordalisa: PETRA MARIA SCHNITZER, Soprano Lay Brother/Giovanni de Salviati: PAUL MCNAMARA, Tenor Pietro Tumoni: JUSTIN HOPKINS, Bass-baritone Arrigo Oldofredi: ROBERT CHAFIN, Tenor Alessio Beneventi: JOHN EASTERLIN, Tenor Sandro da Luzzano: CHRISTOPHER BURCHETT, Baritone Masolino Pedruzzi: MICHAEL SCARCELLE, Bass-baritone Mona Ginevra: ILANA DAVIDSON, Soprano Dianora: LUCY FITZ GIBBON, Soprano Piccarda: KATHERINE MAYSEK, Mezzo-soprano Sisto: JOHN KAWA, Tenor BARD FESTIVAL CHORALE JAMES BAGWELL, Director This evening’s concert will run approximately two hours and 20 minutes including one 20-minute intermission. Used by arrangement with European American Music Distributors Company, sole U.S. and Canadian agent for Universal Edition Vienna, publisher and copyright owner. American Symphony Orchestra welcomes the many organizations who participate in our Community Access Program, which provides free and low-cost tickets to underserved groups in New York’s five boroughs. For information on how you can support this program, please call (212) 868-9276. PLEASE SWITCH OFF YOUR CELL PHONES AND OTHER ELECTRONIC DEVICES. FROM THE Music Director The Stolen Smile DVDs or pirated videos. Opera is the by Leon Botstein one medium from the past that resists technological reproduction. A concert This concert performance of Max von version still represents properly the Schillings’ 1915 Mona Lisa is the latest sonority and the multi-dimensional installment of a series of concert perfor- aspect crucial to the operatic experi- mances of rare operas the ASO has pio- ence. -

Traum Und Abgrund Das Leben Der Schauspielerin Carola Neher Von Marianne Thoms

SWR2 MANUSKRIPT ESSAYS FEATURES KOMMENTARE VORTRÄGE SWR2 Wissen Traum und Abgrund Das Leben der Schauspielerin Carola Neher Von Marianne Thoms Carola Neher, eine Lieblingsschauspielerin Bert Brechts, flieht vor den Nazis nach Moskau, gerät in stalinistischen Terror und stirbt, nach fünf Jahren Lagerhaft, entkräftet an Typhus. Sendung: Freitag, 28. September 2012, 8.30 – 8.58 Uhr Wiederholung, Donnerstag, 02.08.2018 Redaktion: Udo Zindel Regie: Andrea Leclerque Produktion: SWR 2012 Bitte beachten Sie: Das Manuskript ist ausschließlich zum persönlichen, privaten Gebrauch bestimmt. Jede weitere Vervielfältigung und Verbreitung bedarf der ausdrücklichen Genehmigung des Urhebers bzw. des SWR. MANUSKRIPT Regie: Musikblende Klaviermusik Chopin, darüber sprechen: Carola: Man nehme eine beliebige schöne Frau und lasse sie über die Bühne gehen. Sie wird über ihre eigenen Beine und Gedanken stolpern. Sie ist aus ihrem Element gekommen, ein Fisch auf dem Land. Aber wir Schauspielerinnen sind erst auf der Bühne in unserem Element – wir stolpern nur im Leben. Ansager.: Traum und Abgrund – Das Leben der Schauspielerin Carola Neher, 1900 bis 1942. Eine Sendung von Marianne Thoms. Sprecherin: 1 Die gebürtige Münchnerin ist schön, intelligent und hochbegabt. Schon als Kind träumt sich Carola Neher in die Welt des Theaters. Niemand kann sie aufhalten – weder ihr herrschsüchtiger Vater, ein Musiker, noch die besorgte Mutter, eine Gastwirtin. Ihr Bruder Josef sagt über sie: Zitator: Die wäre in jedem Fall Schauspielerin geworden. Und wenn sie im nächsten Jahr daran gestorben wäre. Sprecherin: Mit hemmungslos vitaler Darstellungslust erobert Carola Neher ab ihrem 20. Lebensjahr Bühne für Bühne: Baden-Baden, Nürnberg, München, Breslau – immer zielstrebig mit dem Blick auf Berlin. Mit frechem Vergnügen nutzt sie auch ihre Anziehungskraft auf Männer. -

Brechtian Theory

GUTES TUN 1,3: BRECHTIAN THEORY AND CONTEMPORARY DIDACTIC THEATER by ERICA MARIE HAAS (Under the Direction of Martin Kagel) ABSTRACT The play Gutes Tun 1,3 (2005), written and performed by Anne Tismer and Rahel Savoldelli, lends to comparison to the works of Bertolt Brecht: Tismer and Savoldelli aim to educate the audience about social issues, using Brechtian performance techniques such as Verfremdung to relay their ideas. However, upon closer examination, it is clear that Gutes Tun 1,3 ultimately diverges from Brechtian theory, especially with regard to the way that social messages are conveyed. INDEX WORDS: Gutes Tun, Off-Theater, German theater, Modern theater, Anne Tismer, Rahel Savoldelli, Ballhaus Ost, Bertolt Brecht GUTES TUN 1,3: BRECHTIAN THEORY AND CONTEMPORARY DIDACTIC THEATER by ERICA MARIE HAAS B.A., New College of Florida, 2005 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2009 ©2009 Erica Marie Haas All Rights Reserved iv DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to my friends, especially my best friend, Jessica, for all of her love, support, and silly text messages from across the miles. Priya, Beau, Matt, Amy the Brit, Kristie, JP, Med School Amy, Mike, Alia, Fereshteh, Sam, Lea, and Sarah the Zwiebel are some of the best cheerleaders that a girl could ever hope for. Finally, this thesis is dedicated to my friends from Joe Brown Hall, who have made the past two years in Athens so memorable. Life would not have been as much fun without the basement camaraderie and YouTube prowess of Will, Zachary, Carlos, Justin, Caskey, Monika, Hugh, Flo, Ulla, Boris, Keith, Janith, Antje, Marcie, Lena, Susa, Cassie, Sarah, Katie, and Paulina. -

Saying Yes: Collaboration and Scenography of Man Equals Man Degroot, Anton Degroot, A

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2016 Saying Yes: Collaboration and Scenography of Man Equals Man deGroot, Anton deGroot, A. (2016). Saying Yes: Collaboration and Scenography of Man Equals Man (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/27708 http://hdl.handle.net/11023/3189 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Saying Yes: Collaboration and Scenography of Man Equals Man by Anton deGroot A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF FINE ARTS GRADUATE PROGRAM IN DRAMA CALGARY, ALBERTA MAY 2016 © Anton deGroot 2016 Abstract The following artist’s statement discusses the early inspirations, development, execution of, and reflections upon the scenographic treatment of Bertolt Brecht’s Man Equals Man, directed by Tim Sutherland and produced by the University of Calgary in February of 2015. It details the processes of the set, lights, and properties design, with a focus on the director / scenographer relationship, and an examination of the outcomes. ii Preface It is critical that I mention something at the beginning of this artist’s statement to provide some important context for the reader. -

Weill, Kurt (Julian)

Weill, Kurt (Julian) (b Dessau, 2 March 1900; d New York, 3 April 1950). German composer, American citizen from 1943. He was one of the outstanding composers in the generation that came to maturity after World War I, and a key figure in the development of modern forms of musical theatre. His successful and innovatory work for Broadway during the 1940s was a development in more popular terms of the exploratory stage works that had made him the foremost avant- garde theatre composer of the Weimar Republic. 1. Life. Weill‟s father Albert was chief cantor at the synagogue in Dessau from 1899 to 1919 and was himself a composer, mostly of liturgical music and sacred motets. Kurt was the third of his four children, all of whom were from an early age taught music and taken regularly to the opera. Despite its strong Wagnerian emphasis, the Hoftheater‟s repertory was broad enough to provide the young Weill with a wide range of music-theatrical experiences which were supplemented by the orchestra‟s subscription concerts and by much domestic music-making. Weill began to show an interest in composition as he entered his teens. By 1915 the evidence of a creative bent was such that his father sought the advice of Albert Bing, the assistant conductor at the Hoftheater. Bing was so impressed by Weill‟s gifts that he undertook to teach him himself. For three years Bing and his wife, a sister of the Expressionist playwright Carl Sternheim, provided Weill with what almost amounted to a second home and introduced him a world of metropolitan sophistication.