An Analysis of Personal Transformation and Musical Adaptation in Vocal Compositions of Kurt Weill

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Children in Opera

Children in Opera Children in Opera By Andrew Sutherland Children in Opera By Andrew Sutherland This book first published 2021 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2021 by Andrew Sutherland Front cover: ©Scott Armstrong, Perth, Western Australia All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-6166-6 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-6166-3 In memory of Adrian Maydwell (1993-2019), the first Itys. CONTENTS List of Figures........................................................................................... xii Acknowledgements ................................................................................. xxi Chapter 1 .................................................................................................... 1 Introduction What is a child? ..................................................................................... 4 Vocal development in children ............................................................. 5 Opera sacra ........................................................................................... 6 Boys will be girls ................................................................................. -

Francis Poulenc

CHAN 3134(2) CCHANHAN 33134134 WWideide bbookook ccover.inddover.indd 1 330/7/060/7/06 112:43:332:43:33 Francis Poulenc © Lebrecht Music & Arts Library Photo Music © Lebrecht The Carmelites Francis Poulenc © Stephen Vaughan © Stephen CCHANHAN 33134(2)134(2) BBook.inddook.indd 22-3-3 330/7/060/7/06 112:44:212:44:21 Francis Poulenc (1899 – 1963) The Carmelites Opera in three acts Libretto by the composer after Georges Bernanos’ play Dialogues des Carmélites, revised English version by Joseph Machlis Marquis de la Force ................................................................................ Ashley Holland baritone First Commissioner ......................................................................................James Edwards tenor Blanche de la Force, his daughter ....................................................... Catrin Wyn-Davies soprano Second Commissioner ...............................................................................Roland Wood baritone Chevalier de la Force, his son ............................................................................. Peter Wedd tenor First Offi cer ......................................................................................Toby Stafford-Allen baritone Thierry, a valet ........................................................................................... Gary Coward baritone Gaoler .................................................................................................David Stephenson baritone Off-stage voice ....................................................................................... -

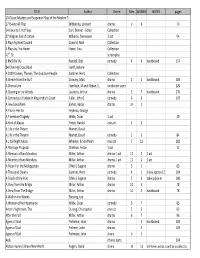

TAG SCRIPT LIBRARY Nov 2013.Xlsx

TITLE Author Genre Men WOMEN NOTES pages 10 Classic Mystery and Suspense Plays of the Modern T 1776‐And All That Wibberley, Leonard drama 98 70 24 Favorite 1 Act Plays Cerf, Bennet ‐ Editor Collection 27 Wagons Full of Cotton Williams, Tennessee 1 act 54 3 Plays by Noel Coward Coward, Noel Collection 3 Plays by Tina Howe Howe, Tina Collection 42nd St. screenplay 6 RMS RIV VU Randall, Bob comedy 4 4 hardbound 157 84 Charring Cross Road Hanff, Helene A 1000 Clowns, Thieves, The Goodbye People Gardner, Herb Collection A Breeze from the Gulf Crowley, Mart drama 2 1 hardbound 184 A Chorus Line Hamlisch, M.and Kleban, E, . conductor score 220 A Clearing in the Woods Laurents, Arthur drama 5 5 hardbound 170 A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court Fuller, John G. comedy 6 6 147 A Few Good Men Sorkin, Aaron drama 14 1 A Flea in Her Ear Feydeau, George A Florentine Tragedy Wilde, Oscar 1 act 20 A Kind of Alaska Pinter, Harold one act 1 2 A Life in the Theare Mamet, David A Life in the Theatre Mamet, David comedy 2 0 84 A Little Night Music Wheeler, & Sondheim musical 7 11 182 A Marriage Proposal Chekhov, Anton 1 act 12 A Memory of two Mondays Miller, Arthur drama‐1 act 12 2 1 act A Memory of two Mondays Miller, Arthur drama‐1 act 12 2 1 act A Moon For the Misbegotten O'Neill, Eugene drama 3 1 83 A Thousand Clowns Gardner, Herb comedy 4 1 1 boy approx 12 104 A Touch of the Poet O'Neill, Eugene drama 7 3 takes place in 180 A View from the Bridge Miller, Arthur drama 10 3 78 A View From The Bridge Miller, Arthur drama 10 3 hardbound 78 A Walk -

Assisted by Katie Rowan, Accompanist

THE BELHAVEN UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC Dr. Stephen W. Sachs, Chair presents Morgan Robertson & Ellie Wise Junior Voice Recital assisted by Katie Rowan, Accompanist Tuesday, April 9, 2013 • 7:30 p.m. Belhaven University Center for the Arts • Concert Hall There will be a reception after the program. Please come and greet the performers. Please refrain from the use of all flash and still photography during the concert. Please turn off all pagers and cell phones. PROGRAM I Wish It So from Juno Marc Blitzstein • 1905 - 1964 My Ship from Lady in the Dark Kurt Weill • 1900 - 1950 Ira Gershwin • 1896 - 1983 Morgan Robertson, Soprano; Katie Rowan, Accompanist Out There from Hunchback of Notre Dame Stephen Schwarts • b. 1948 Alan Menken • b. 1949 There Won’t Be Trumpets from Anyone Can Whistle Stephen Sondhiem • b. 1930 Ellie Wise, Soprano; Katie Rowan, Accompanist Take Me to the World from Evening Primrose Stephen Sondheim The Girls of Summer from Marry Me a Little Morgan Robertson, Soprano; Katie Rowan, Accompanist Glamorous Life from A Little Night Music Stephen Sondheim My New Philosophy from You’re a Good Man, Charlie Brown Clark Gesner • 1938 - 2002 Ellie Wise, Soprano; Katie Rowan, Accompanist Mr. Snow from Carousel Richard Rodgers • 1902 - 1979 Oscar Hammerstein II • 1895 - 1960 Morgan Robertson, Soprano; Katie Rowan, Accompanist My Party Dress from Henry and Mudge Kait Kerrigan • b. 1981 Brian Loudermilk • b. 1983 Ellie Wise, Soprano; Katie Rowan, Accompanist INTERMISSION Always a Bridesmaid from I Love You, You’re Perfect, Now Change Jimmy Roberts Morgan Robertson, Soprano; Katie Rowan, Accompanist Music and the Mirror from A Chorus Line Joe DiPietro • b. -

Nl262-2 Rev:Layout 1.Qxd

Volume 26 Number 2 topical Weill Fall 2008 A supplement to the Kurt Weill Newsletter news & news events The Firebrand Returns Weill’s 1945 operetta with lyrics by Ira Gershwin and book by Edwin Justus Mayer, The Firebrand of Florence, will return to New York on 12 March 2009 for the first time since its ill-fated Broadway run. The Collegiate Chorale has assem- bled an all-star cast for the occasion, including Nathan Gunn (Benvenuto Cellini, the “Firebrand”), Anna Christy (Angela), and Terrence Mann (Duke). Lincoln Center’s Alice Tully Hall provides the venue for a concert performance directed and narrated by Roger Rees; Paul Gemignani conducts. Other Notable Productions Montreal audiences will have the opportunity to see François Girard’s acclaimed Opéra de Lyon 2006 double bill of Der Lindberghflug and Die sieben Todsünden when the production travels to the Montreal High Lights Festival next February after successful tours to the 2006 Edinburgh Festival and to the Anna Christy Nathan Gunn 2008 New Zealand International Arts Festival in Wellington. Four performances of Girard’s imaginative and luminous staging are scheduled for 18-21 February 2009. Charles Workman plays Lindbergh, and Magdalena Anna Hofmann plays Anna I to seven different Anna IIs (one per sin); Walter Boudreau conducts the Société de Musique Contemporaine du Québec. HK Gruber will lead the Klangforum Wien and Chorus Sine Nomine in a June 2009 European tour of Die Dreigroschenoper performed in concert. The multi-nation- al cast includes Ian Bostridge (Macheath), Hanna Schwarz (Celia Peachum), Dorothea Röschmann (Polly Peachum), Angelika Kirchschlager (Jenny), Florian Boesch (Tiger Brown), Lydia Teuscher (Lucy), and Christoph Bantzer (Narrator). -

Brecht's Antigone in Performance

PERFORMANCE PHILOSOPHY RHYTHM AND STRUCTURE: BRECHT’S ANTIGONE IN PERFORMANCE BRUNO C. DUARTE FCSH UNIVERSIDADE NOVA DE LISBOA Brecht’s adaptation of Sophocles’ Antigone in 1948 was openly a political gesture that aspired to the complete rationalization of Greek Tragedy. From the beginning, Brecht made it his task to wrench ancient tragic poetry out of its ‘ideological haze’, and proceeded to dismantle and eliminate what he named the ‘element of fate’, the crucial substance of tragic myth itself. However, his encounter with Hölderlin's unorthodox translation of Antigone, the main source for his appropriation and rewriting of the play, led him to engage in a radical experiment in theatrical practice. From the isolated first performance of Antigone, a model was created—the Antigonemodell —that demanded a direct confrontation with the many obstacles brought about by the foreign structure of Greek tragedy as a whole. In turn, such difficulties brought to light the problem of rhythm in its relation to Brecht’s own ideas of how to perform ancient poetry in a modern setting, as exemplified by the originally alienating figure of the tragic chorus. More importantly, such obstacles put into question his ideas of performance in general, as well as the way they can still resonate in our own understanding of what performance is or might be in a broader sense. 1947–1948: Swabian inflections It is known that upon returning from his American exile, at the end of 1947, Bertolt Brecht began to work on Antigone, the tragic poem by Sophocles. Brecht’s own Antigone premiered in the Swiss city of Chur on February 1948. -

Kennedy Center Education Department. Funding Also Provided by the Kennedy Center Corporate Fund

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 381 839 CS 508 906 AUTHOR Carr, John C. TITLE "Crazy for You." Spotlight on Theater Notes. INSTITUTION John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, Washington, D.C. SPONS AGENCY Department of Education, Washington, DC. PUB DATE [95] NOTE 17p.; Produced by the Performance Plus Program, Kennedy Center Education Department. Funding also provided by the Kennedy Center Corporate Fund. For other guides in this series, see CS 508 902-905. PUB TYPE Guides General (050) EDRS PRTCE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Acting; *Cultural Enrichment; *Drama; Higher Education; Playwriting; Popular Culture; Production Techniques; Secondary Education IDENTIFIERS *Crazy for You; Historical Background; Musicals ABSTRACT This booklet presents a variety of materials concerning the musical play "Crazy for You," a recasting of the 1930 hit. "Girl Crazy." After a brief historical introduction to the musical play. the booklet presents biographical information on composers George and Ira Gershwin, the book writer, the director, the star choreographer, various actors in the production, the designers, and the musical director. The booklet also offers a quiz about plays. and a 7-item list of additional readings. (RS) ....... ; Reproductions supplied by EDRS ore the best that can he made from the original document, U S DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION Ofi.co ofEaucabonni Research aria improvement EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION CENTER IERIC1 Et This document has been reproduced as received from the person or organization onqinallnq d 0 Minor charms have been made to improve reproduction quality. Points or view or opinions stated in this document do not necessarily represent official OERI position or policy -1411.1tn, *.,3^ ..*. -

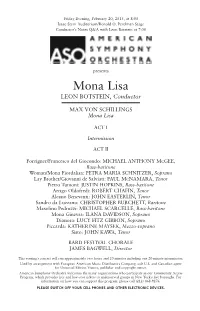

Mona Lisa LEON BOTSTEIN, Conductor

Friday Evening, February 20, 2015, at 8:00 Isaac Stern Auditorium/Ronald O. Perelman Stage Conductor’s Notes Q&A with Leon Botstein at 7:00 presents Mona Lisa LEON BOTSTEIN, Conductor MAX VON SCHILLINGS Mona Lisa ACT I Intermission ACT II Foreigner/Francesco del Giocondo: MICHAEL ANTHONY MCGEE, Bass-baritone Woman/Mona Fiordalisa: PETRA MARIA SCHNITZER, Soprano Lay Brother/Giovanni de Salviati: PAUL MCNAMARA, Tenor Pietro Tumoni: JUSTIN HOPKINS, Bass-baritone Arrigo Oldofredi: ROBERT CHAFIN, Tenor Alessio Beneventi: JOHN EASTERLIN, Tenor Sandro da Luzzano: CHRISTOPHER BURCHETT, Baritone Masolino Pedruzzi: MICHAEL SCARCELLE, Bass-baritone Mona Ginevra: ILANA DAVIDSON, Soprano Dianora: LUCY FITZ GIBBON, Soprano Piccarda: KATHERINE MAYSEK, Mezzo-soprano Sisto: JOHN KAWA, Tenor BARD FESTIVAL CHORALE JAMES BAGWELL, Director This evening’s concert will run approximately two hours and 20 minutes including one 20-minute intermission. Used by arrangement with European American Music Distributors Company, sole U.S. and Canadian agent for Universal Edition Vienna, publisher and copyright owner. American Symphony Orchestra welcomes the many organizations who participate in our Community Access Program, which provides free and low-cost tickets to underserved groups in New York’s five boroughs. For information on how you can support this program, please call (212) 868-9276. PLEASE SWITCH OFF YOUR CELL PHONES AND OTHER ELECTRONIC DEVICES. FROM THE Music Director The Stolen Smile DVDs or pirated videos. Opera is the by Leon Botstein one medium from the past that resists technological reproduction. A concert This concert performance of Max von version still represents properly the Schillings’ 1915 Mona Lisa is the latest sonority and the multi-dimensional installment of a series of concert perfor- aspect crucial to the operatic experi- mances of rare operas the ASO has pio- ence. -

Brechtian Theory

GUTES TUN 1,3: BRECHTIAN THEORY AND CONTEMPORARY DIDACTIC THEATER by ERICA MARIE HAAS (Under the Direction of Martin Kagel) ABSTRACT The play Gutes Tun 1,3 (2005), written and performed by Anne Tismer and Rahel Savoldelli, lends to comparison to the works of Bertolt Brecht: Tismer and Savoldelli aim to educate the audience about social issues, using Brechtian performance techniques such as Verfremdung to relay their ideas. However, upon closer examination, it is clear that Gutes Tun 1,3 ultimately diverges from Brechtian theory, especially with regard to the way that social messages are conveyed. INDEX WORDS: Gutes Tun, Off-Theater, German theater, Modern theater, Anne Tismer, Rahel Savoldelli, Ballhaus Ost, Bertolt Brecht GUTES TUN 1,3: BRECHTIAN THEORY AND CONTEMPORARY DIDACTIC THEATER by ERICA MARIE HAAS B.A., New College of Florida, 2005 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2009 ©2009 Erica Marie Haas All Rights Reserved iv DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to my friends, especially my best friend, Jessica, for all of her love, support, and silly text messages from across the miles. Priya, Beau, Matt, Amy the Brit, Kristie, JP, Med School Amy, Mike, Alia, Fereshteh, Sam, Lea, and Sarah the Zwiebel are some of the best cheerleaders that a girl could ever hope for. Finally, this thesis is dedicated to my friends from Joe Brown Hall, who have made the past two years in Athens so memorable. Life would not have been as much fun without the basement camaraderie and YouTube prowess of Will, Zachary, Carlos, Justin, Caskey, Monika, Hugh, Flo, Ulla, Boris, Keith, Janith, Antje, Marcie, Lena, Susa, Cassie, Sarah, Katie, and Paulina. -

Weill, Kurt (Julian)

Weill, Kurt (Julian) (b Dessau, 2 March 1900; d New York, 3 April 1950). German composer, American citizen from 1943. He was one of the outstanding composers in the generation that came to maturity after World War I, and a key figure in the development of modern forms of musical theatre. His successful and innovatory work for Broadway during the 1940s was a development in more popular terms of the exploratory stage works that had made him the foremost avant- garde theatre composer of the Weimar Republic. 1. Life. Weill‟s father Albert was chief cantor at the synagogue in Dessau from 1899 to 1919 and was himself a composer, mostly of liturgical music and sacred motets. Kurt was the third of his four children, all of whom were from an early age taught music and taken regularly to the opera. Despite its strong Wagnerian emphasis, the Hoftheater‟s repertory was broad enough to provide the young Weill with a wide range of music-theatrical experiences which were supplemented by the orchestra‟s subscription concerts and by much domestic music-making. Weill began to show an interest in composition as he entered his teens. By 1915 the evidence of a creative bent was such that his father sought the advice of Albert Bing, the assistant conductor at the Hoftheater. Bing was so impressed by Weill‟s gifts that he undertook to teach him himself. For three years Bing and his wife, a sister of the Expressionist playwright Carl Sternheim, provided Weill with what almost amounted to a second home and introduced him a world of metropolitan sophistication. -

Lawrence, Fall 2019 Lawrence University

Lawrence University Lux Alumni Magazines Communications Fall 2019 Lawrence, Fall 2019 Lawrence University Follow this and additional works at: https://lux.lawrence.edu/alumni_magazines Part of the Liberal Studies Commons © Copyright is owned by the author of this document. Recommended Citation Lawrence University, "Lawrence, Fall 2019" (2019). Alumni Magazines. 115. https://lux.lawrence.edu/alumni_magazines/115 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Communications at Lux. It has been accepted for inclusion in Alumni Magazines by an authorized administrator of Lux. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FALL 2019 LAWRENCE Wan·der·jahr: n. noun, [vahn-duh r-yahr] /'van d re , ya r/ German. 1. A year or period of travel, especially following one’s schooling and before practicing a profession. 2. A life-changing year of exploration, discovery, and independence funded by the Thomas J. Watson Foundation. Greetings from Appleton! LAWRENCE They say in Wisconsin there are two seasons of the year: winter and EDITOR construction. We are in the second season, which brings physical renewal Kelly B. Landiſ Not All of campus. It is also celebration season here at Lawrence, with two of ART DIRECTORS my favorite moments of the year: Commencement, when we sent 350 Liz Boutelle, Matt Schmeltzer graduates out to begin their lives after Lawrence, and Reunion, when ASSOCIATE VICE PRESIDENT OF we welcomed more than a thousand of them back to reconnect with the COMMUNICATIONS Megan Scott community we share. Over the course of those two weekends, we hosted Who Wander close to 1,000 people in the President’s House. -

MUSIC PROGRAM Voxso: LUTHERAN SUMMER MUSIC ACADEMY & FESTIVAL Lutheran Summer Music & Sounds of Summer Institute Concert & Recital Series

LUTHERAN MUSIC PROGRAM voxso: LUTHERAN SUMMER MUSIC ACADEMY & FESTIVAL Lutheran Summer Music & Sounds of Summer Institute Concert & Recital Series Faculty Artist Recital Sine Nomine Vocal Ensemble Catherine McCord Larsen, soprano Penny Hogan, soprano KrisAnne Weiss, mezzo-soprano Brad Bradshaw, tenor Michael Scarbrough, baritone George Hogan, bass Cheryl Lemmons, piano Noble Recital Hall Luther College Tuesday, July 12, 2016 7:30 p.m. Program !. American Traditions Hard Times Come Again No More Stephen Foster (1826-1864) arr. Mark Keller Wayfarin’ Stranger Traditional arr. Gilbert M. Martin (b. 1941) My Lord, What a Mornin’ Traditional arr. Harry T. Burleigh (1866-1949) Ride On, King Jesus Traditional arr. Moses Hogan (1957-2003) I. Kurt Weill in America from Lost in the Stars Kurt Weill Lost in the Stars (1900-1950) lyrics by Maxwell Anderson arr. Paris Rutherford from Street Scene lyrics by Langston Hughes Lonely House Brad Bradshaw, tenor What Good Would the Moon Be? Penny Hogan, soprano We’ll Go Away Together Brad Bradshaw, tenor Catherine McCord Larsen, soprano from One Touch of Venus lyrics by Ogden Nash I’m a Stranger Here Myself KrisAnne Weiss, mezzo-soprano from Love Life lyrics by Alan Jay Lerner This is the Life Michael Scarbrough, baritone from Knickerbocker Holiday lyrics by Maxwell Anderson September Song George Hogan, bass from Lady in the Dark lyrics by Ira Gershwin The Saga of Jenny Ill. George Gershwin from Porgy and Bess George Gershwin Summertime (1898-1937) lyrics by DuBose Heyward and Ira Gershwin from Lady Be Good lyrics by Ira Gershwin Fascinatin’ Rhythm from Porgy and Bess Oh Lawd, I’m On My Way Program Notes Our program tonight includes examples of many of American music’s strongest traditions: parlor songs intended to be played in the homes of amateur musicians, folk tunes and African-American spirituals shared and changed through oral tradition, and jazz-influenced musical theater and opera.