Brecht's Antigone in Performance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Musical Hybridization and Political Contradiction: the Success of Arthur Honeggerâ•Žs Antigone in Vichy France

Butler Journal of Undergraduate Research Volume 7 2021 Musical Hybridization and Political Contradiction: The Success of Arthur Honegger’s Antigone in Vichy France Emma K. Schubart University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/bjur Recommended Citation Schubart, Emma K. (2021) "Musical Hybridization and Political Contradiction: The Success of Arthur Honegger’s Antigone in Vichy France," Butler Journal of Undergraduate Research: Vol. 7 , Article 4. Retrieved from: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/bjur/vol7/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Scholarship at Digital Commons @ Butler University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Butler Journal of Undergraduate Research by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Butler University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BUTLER JOURNAL OF UNDERGRADUATE RESEARCH, VOLUME 7 MUSICAL HYBRIDIZATION AND POLITICAL CONTRADICTION: THE SUCCESS OF ARTHUR HONEGGER’S ANTIGONE IN VICHY FRANCE EMMA K. SCHUBART, UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA, CHAPEL HILL MENTOR: SHARON JAMES Abstract Arthur Honegger’s modernist opera Antigone appeared at the Paris Opéra in 1943, sixteen years after its unremarkable premiere in Brussels. The sudden Parisian success of the opera was extraordinary: the work was enthusiastically received by the French public, the Vichy collaborationist authorities, and the occupying Nazi officials. The improbable wartime triumph of Antigone can be explained by a unique confluence of compositional, political, and cultural realities. Honegger’s compositional hybridization of French and German musical traditions, as well as his opportunistic commercial motivations as a Swiss composer working in German-occupied France, certainly aided the success of the opera. -

Carl Orffs Hesperische Musik

MATTHIAS JOHANNES PERNERSTORFER / WIEN Carl Orffs hesperische Musik Carl Orffs ‚Antigonae‘ (1940–49) und ‚Oedi pus der Tyrann‘ (1951– 58) nach Sophokles in der Übersetzung von Friedrich Hölderlin sowie der aischyleische ‚Prometheus‘ (1963–67) in der Originalsprache gehören zu den bedeutendsten Beiträgen zur musikalischen Rezeption der Antike im 20. Jahrhundert. Ich folge Stefan Kunze im Gebrauch der Bezeichnung Tragödien-Bearbeitungen für die genannten Bühnenwerke, da „kein musi- kalisches Werk (Vertonung) auf der Grundlage eines Tragödientextes … das Ziel [ist] …, sondern die [interpretative, Anm. d. A.1 ] Darstellung der Tragödie mit musikalischen Mitteln“.2 Es handelt sich um eine Form des Musiktheaters ganz eigener Art – „gleich weit entfernt vom Sprechtheater herkömmlicher Prägung wie von der Oper und von der … Bühnenmusik“.3 Auch wenn der Musikhistoriker Werner Schubert vor einigen Jahren dia- gnostizierte: „Daß es [Orff] … nicht um eine Rekonstruktion antiker Aufführungspraxis ging, muß man heute nicht mehr eigens betonen“,4 so möchte ich anmerken, daß die Tragödien-Bearbeitungen Orffs von vielen Philologen wie Theaterwissenschaftlern, die die musikwissenschaftliche Diskussion nicht mitverfolgen, wohl noch immer – sei es zustimmend oder ablehnend – als Rekonstruktionsversuche rezipiert werden. Der Grund dafür liegt in der zum Teil euphorischen Reaktion von zeitgenössischen Philologen, durch die Orffs Werke den Stellenwert von authentischen Wie- dergaben der altgriechischen Tragödien erreichten. Jahrzehntelang widmete sich Carl Orff den Tragödien-Bearbeitungen, wobei nicht von einem Weg des Komponisten in die Geistes- oder Musik- welt der Antike gesprochen werden kann. DieAntike diente ihm in Form —————————— 1 Zum Interpretationscharakter dieser „Darstellung der Tragödie“ s.u. 2 Kunze 1998, 547. 3 Schubert 1998, 405. 4 Schubert 1998, 403. 122 Matthias Johannes Pernerstorfer ihrer Texte als Medium, das er im Sinne von Höl derlins Antikerezeption mit Blick auf eine abendländische Gegenwart – deshalb ‚hesperisch‘ – gestaltete. -

Surviving Antigone: Anouilh, Adaptation, and the Archive

SURVIVING ANTIGONE: ANOUILH, ADAPTATION AND THE ARCHIVE Katelyn J. Buis A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2014 Committee: Cynthia Baron, Advisor Jonathan Chambers ii ABSTRACT Dr. Cynthia Baron, Advisor The myth of Antigone has been established as a preeminent one in political and philosophical debate. One incarnation of the myth is of particular interest here. Jean Anouilh’s Antigone opened in Paris, 1944. A political and then philosophical debate immediately arose in response to the show. Anouilh’s Antigone remains a well-known play, yet few people know about its controversial history or the significance of its translation into English immediately after the war. It is this history and adaptation of Anouilh’s contested Antigone that defines my inquiry. I intend to reopen interpretive discourse about this play by exploring its origins, its journey, and the archival limitations and motivations controlling its legacy and reception to this day. By creating a space in which multiple readings of this play can exist, I consider adaptation studies and archival theory and practice in the form of theatre history, with a view to dismantle some of the misconceptions this play has experienced for over sixty years. This is an investigation into the survival of Anouilh’s Antigone since its premiere in 1944. I begin with a brief overview of the original performance of Jean Anouilh’s Antigone and the significant political controversy it caused. The second chapter centers on the changing reception of Anouilh’s Antigone beginning with the liberation of Paris to its premiere on the Broadway stage the following year. -

Sophocles' Antigone Reworked in the Twentieth

NEW VOICES IN CLASSICAL RECEPTION STUDIES Issue 12 (2018) SOPHOCLES’ ANTIGONE REWORKED IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY: THE CASE OF HASENCLEVER’S ANTIGONE (1917) © Rossana Zetti (University of Edinburgh) INTRODUCTION AND CONTEXTUALIZATION This article examines a little-known example of Antigone’s reception in the twentieth century: the adaptation by the German expressionist writer Walter Hasenclever. This version is the first and arguably most innovative of several European adaptations of Sophocles’ play to appear in the first half of the twentieth century. Although successful at the time of its production, Hasenclever’s Antigone is scarcely read in contemporary scholarship and is discussed mainly in German-language scholarship.1 Whereas Flashar’s wide-ranging study, in German, refers to Hasenclever’s drama (Flashar 2009: 127– 29), in Fischer-Lichte’s 2017 book Tragedy’s Endurance, in English, Hasenclever appears only in one endnote (Fischer-Lichte 2017: 143). The only English translation of the play available (Ritchie and Stowell 1969: 113–60) is rather out of date and inaccessible. Hasenclever’s Antigone is briefly mentioned in Steiner’s essential reference book Antigones (Steiner 1984: 142; 146; 170; 218), in the chapter on Antigone in the recent Brill’s Companion to the Reception of Sophocles (Silva 2017: 406–7) and in Cairns’ 2016 book on Sophocles’ Antigone (Cairns 2016: 133). However, it is absent in some of the most recent contributions dedicated to the play’s modern reception, including Wilmer’s and Žukauskaitė’s edited collection on Antigone in postmodern thought (2010), Mee’s and Foley’s essays (2011) discussing adaptations of Antigone staged around the world, and Morais’, Hardwick’s and Silva’s recent volume (2017).2 The absence of Hasenclever from contemporary scholarship can be explained by the fact that his Antigone lacks the complexity of later adaptations, such as Anouilh’s and Brecht’s. -

Kodály and Orff: a Comparison of Two Approaches in Early Music Education

ZKÜ Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi, Cilt 8, Sayı 15, 2012 ZKU Journal of Social Sciences, Volume 8, Number 15, 2012 KODÁLY AND ORFF: A COMPARISON OF TWO APPROACHES IN EARLY MUSIC EDUCATION Yrd.Doç.Dr. Dilek GÖKTÜRK CARY Karabük Üniversitesi Safranbolu Fethi Toker Güzel Sanatlar ve Tasarım Fakültesi Müzik Bölümü [email protected] ABSTRACT The Hungarian composer and ethnomusicologist Zoltán Kodály (1882-1967) and the German composer Carl Orff (1895-1982) are considered two of the most influential personalities in the arena of music education during the twentieth-century due to two distinct teaching methods that they developed under their own names. Kodály developed a hand-sign method (movable Do) for children to sing and sight-read while Orff’s goal was to help creativity of children through the use of percussive instruments. Although both composers focused on young children’s musical training the main difference between them is that Kodály focused on vocal/choral training with the use of hand signs while Orff’s main approach was mainly on movement, speech and making music through playing (particularly percussive) instruments. Finally, musical creativity via improvisation is the main goal in the Orff Method; yet, Kodály’s focal point was to dictate written music. Key Words: Zoltán Kodály, Carl Orff, The Kodály Method, The Orff Method. KODÁLY VE ORFF: ERKEN MÜZİK EĞİTİMİNDE KULLANILAN İKİ METODUN BİR KARŞILAŞTIRMASI ÖZET Macar besteci ve etnomüzikolog Zoltán Kodály (1882-1967) ve Alman besteci Carl Orff (1895-1982) geliştirmiş oldukları farklı 2 öğretim metodundan dolayı 20. yüzyılda müzik eğitimi alanında en etkili 2 kişi olarak anılmaktadırlar. Kodály çocukların şarkı söyleyebilmeleri ve deşifre yapabilmeleri için el işaretleri metodu (gezici Do) geliştirmiş, Orff ise vurmalı çalgıların kullanımı ile çocukların yaratıcılıklarını geliştirmeyi hedef edinmiştir. -

Enescu US 3/11/05 11:27 Page 16

660163-64 bk Enescu US 3/11/05 11:27 Page 16 ENESCU 2 CDs Oedipe Pederson • Silins • Damiani • Lipov‰ek Chorus and Orchestra of the Vienna State Opera Michael Gielen Above: Oedipus (Monte Pederson) Right: Michael Gielen 8.660163-64 16 660163-64 bk Enescu US 3/11/05 11:27 Page 2 George ENESCU (1881-1955) Oedipe, Op. 23 (Tragédie lyrique en 4 actes et 6 tableaux) Libretto by Edmond Fleg Below and right: Oedipus (Monte Pederson) Oedipe . Monte Pederson, Bass-baritone Tirésias . Egils Silins, Bass Créon . Davide Damiani, Baritone Le berger (The Shepherd) . Michael Roider, Tenor Le grand prêtre (The High Priest) . Goran Simi´c, Bass Phorbas . Peter Köves, Bass Le veilleur (The Watchman) . Walter Fink, Bass Thésée . Yu Chen, Baritone Laïos . Josef Hopferwieser, Tenor Jocaste/La Sphinge (The Sphinx) . Marjana Lipov‰ek, Mezzo-soprano Antigone . Ruxandra Donose, Soprano Mérope . Mihaela Ungureanu, Mezzo-soprano Chorus of the Vienna State Opera Répétiteur: Erwin Ortner Vienna Boys Choir Orchestra of the Vienna State Opera Stage Orchestra of the Austrian Federal Theatres Michael Gielen 8.660163-64 2 15 8.660163-64 660163-64 bk Enescu US 3/11/05 11:27 Page 14 CD 1 63:53 CD 2 64:33 Act I (Prologue) Act III 1 Prelude 4:31 1 Oh! Oh! Hélas! Hélas! 9:04 (Chorus, Oedipus, High Priest, Creon) 2 Roi Laïos, en ta maison 6:56 (Women, High Priest, Warriors, 2 Divin Tirésias, très cher, très grand 6:02 Shepherds, Creon) (Oedipus, Tiresias, Creon, Chorus) 3 Les Dieux ont béni l’enfant 8:11 3 Qu’entends-je, Oedipe? 12:37 (High Priest, Jocasta, Laius, (Jocasta, -

In the Realm of Politics, Nonsense, and the Absurd: the Myth of Antigone in West and South Slavic Drama in the Mid-Twentieth Century

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4312/keria.20.3.95-108 Alenka Jensterle-Doležal In the Realm of Politics, Nonsense, and the Absurd: The Myth of Antigone in West and South Slavic Drama in the Mid-Twentieth Century Throughout history humans have always felt the need to create myths and legends to explain and interpret human existence. One of the classical mythi- cal figures is ancient Antigone in her torment over whether to obey human or divine law. This myth is one of the most influential myths in European literary history. In the creation of literature based on this myth there have always been different methods and styles of interpretation. Literary scholars always emphasised its philosophical and anthropological dimensions.1 The first variants of the myth of Antigone are of ancient origin: the playAntigone by Sophocles (written around 441 BC) was a model for others throughout cultural and literary history.2 There are various approaches to the play, but the well-established central theme deals with one question: the heroine Antigone is deeply convinced that she has the right to reject society’s infringement on her freedom and to act, to recognise her familial duty, and not to leave her brother’s body unburied on the battlefield. She has a personal obligation: she must bury her brother Polyneikes against the law of Creon, who represents the state. In Sophocles’ play it is Antigone’s stubbornness transmitted into action 1 Cf. also: Simone Fraisse, Le mythe d’Antigone (Paris: A. Colin, 1974); Cesare Molinari, Storia di Antigone da Sofocle al Living theatre: un mito nel teatro occidentale (Bari: De Donato, 1977); George Steiner, Antigones (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1984); Elisabeth Frenzel, Stoffe der Weltlitera- tur: Ein Lexikon Dichtungsgeschichtlicher Längsschnitte, 5. -

Wolf-Dieter Narr Niemands-Herrschaft

Wolf-Dieter Narr Niemands-Herrschaft Eine Einführung in Schwierigkeiten, Herrschaft zu begreifen Herausgegeben von Uta v. Winterfeld V VS Wolf-Dieter Narr Niemands-Herrschaft Wolf-Dieter Narr, Politikwissenschaftler, war von 1971 bis 2002 Professor am Otto-Suhr-Institut der Freien Universität Berlin, Mitgründer und Mitsprecher des Komitees für Grundrechte und Demokratie. Uta von Winterfeld, Politikwissenschaftlerin, ist Projektleiterin am Wuppertal Institut für Klima, Umwelt, Energie und Privatdozentin am Otto-Suhr-Institut der Freien Universität Berlin. Wolf-Dieter Narr Niemands-Herrschaft Eine Einführung in Schwierigkeiten, Herrschaft zu begreifen Herausgegeben von Uta v. Winterfeld VSA: Verlag Hamburg www.vsa-verlag.de Die Drucklegung wird finanziell gefördert von der Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung. © VSA: Verlag 2015, St. Georgs Kirchhof 6, 20099 Hamburg Alle Rechte vorbehalten Umschlaggestaltung unter Verwendung eines Bildes von Johann Heinrich Wilhelm Tischbein (1751-1829) mit dem Motiv »Odysseus flieht mit seinen Gefährten im Schiff vor Polyphem« Druck- und Buchbindearbeiten: CPI Books GmbH, Leck ISBN 978-3-89965-600-8 Inhalt Prolog ........................................................................................................................ 9 Kapitel I Jeder und Jedem ihre oder seine »Theorie« ? ................................................. 13 Theorie und Wirklichkeit ...................................................................................... 13 Theorie und Praxis ................................................................................................ -

What to Do with Gestus Today Version II

Abstract This thesis explores the common and dialectical features of pedagogy, Bertolt Brecht’s Gestus, and identity construction. It speaks from the perspectives of pedagogue, actor and subject. It argues that in each of these modes the subject is necessarily engaged in both an ontological dilemma and opportunity, which is performative. It exposes embodiment as an oscillatory process of absence and presence. This is predicated on the impossibility of arriving at a fixed notion of being in the world. The thesis is set within an autobiographical frame. First because each mode marks an encounter in the life of Rob Vesty, and second because the practice-based-research uses autobiographical performance. It advances by constructing a piece of performative writing, an autobiographical timeline, to affect an experience of the practice, which informs this thesis. This piece introduces a montage of three juxtaposing studies. The first draws on Rob Vesty’s work in TIE with Splendid Productions and uses the company’s 2007/2008 performance and workshop tour of Brecht’s The Good Woman of Szechuan. It argues that a dialectic, rather than didactic, process must occur in the pedagogic setting and that this is dependent on the presence of a creative gap produced by a strong aesthetic. The second study then argues that the Gestic actor embodies and ‘writes’ this creative gap in a parodic way and that a virtue is made of showing its construction. The final study turns to Rob Vesty’s (2008) solo theatre show – One Man Good Woman – to chart the way identity impacts upon autobiography. It argues that the ‘written’ nature of autobiography and identity renders the subject both absent and present and retains dialectical features in its construction. -

Of Music PROGRAM

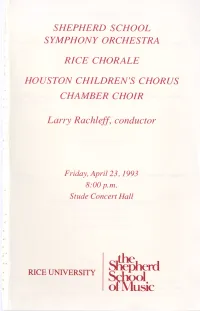

SHEPHERD SCHOOL SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA RICE CHORALE HOUSTON CHILDREN'S CHORUS CHAMBER CHOIR Larry Rachleff, conductor Friday, April23, 1993 8:00p.m. Stude Concert Hall "-' sfkteherd RICE UNIVERSITY Sc~ol Of Music PROGRAM Fanfare for a Great City Arthur Gottschalk (b. 1952) Variations on a Theme of Joseph Haydn, Op. 56a Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) INTERMISSION Carmina Burana Carl Orff ( 1895-1982) Rice Chorale Houston Children's Chorus Chamber Choir Kelley Cooksey, soprano Francisco Almanza, tenor Robert Ames, baritone In consideration of the performers and members of the audience, please check audible paging devices with the ushers and silence audible timepieces. The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment are prohibited. SHEPHERD SCHOOL SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Violin I Viola (cont.) Oboe Trumpet (cont.) Julie Savignon, Erwin Foubert Margaret Butler Troy Rowley concertmaster Patrick Horn Kyle Bruckmann David Workman Claudia Harrison Stephanie Griffin Jeffrey Champion Trombone Barbara Wittenberg Bin Sun Dione Chandler Wade Demmert Jeanine Tiemeyer Andrew Weaver Karen Friedman David Ford Kristin Lacey Sharon Neufeld ~ Brent Phillips Mihaela Oancea English Horn Cello Kyle Bruckmann Inga Ingver Tuba Katherine de Bethune, Yenn Chwen Er Clarinet Jeffrey Tomberg principal Yoong-han Chan Benjamin Brady Danny Urban ~ Jeanne Jaubert Magdalena Villegas Joanne Court Scott Brady Timpani and Tanya Schreiber Kelly Cramm Mary Ellen Morris Percussion Rebecca Ansel Martin van Maanen Robin Creighton Douglas Cardwell Eitan Ornoy X in-Yang Zhou Amy -

An Analysis of Personal Transformation and Musical Adaptation in Vocal Compositions of Kurt Weill

University of Mississippi eGrove Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors Theses Honors College) 2011 An Analysis of Personal Transformation and Musical Adaptation in Vocal Compositions of Kurt Weill Elizabeth Rose Williamson Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis Recommended Citation Williamson, Elizabeth Rose, "An Analysis of Personal Transformation and Musical Adaptation in Vocal Compositions of Kurt Weill" (2011). Honors Theses. 2157. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis/2157 This Undergraduate Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College) at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AN ANALYSIS OF PERSONAL TRANSFORMATION AND MUSICAL ADAPTATION IN VOCAL COMPOSITIONS OF KURT WEILL by Elizabeth Rose Williamson A thesis submitted to the faculty of The University of Mississippi in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College. Oxford May 2011 Approved by Reader: Professor Corina Petrescu Reader: Professor Charles Gates I T46S 2^1 © 2007 Elizabeth Rose Williamson ALL RIGHTS RESERVED II ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the people of the Kurt Weill Zentrum in Dessau Gennany who graciously worked with me despite the reconstruction in the facility. They opened their resources to me and were willing to answer any and all questions. Thanks to Clay Terry, I was able to have an uproariously hilarious ending number to my recital with “Song of the Rhineland.” I thank Dr. Charles Gates for his attention and interest in my work. -

Bertolt Brecht B

Bertolt Brecht b. Feb. 10, 1898, Augsburg d. Aug. 14, 1956, East Berlin EUGEN BERTHOLD FRIEDRICH BRECHT, German poet, playwright, and theatrical reformer whose epic theatre departed from the conventions of theatrical illusion and developed the drama as a social and ideological forum for leftist causes. Brecht was, first, a superior poet, with a command of many styles and moods. As a playwright he was an intensive worker, a restless piecer-together of ideas not always his own (The Threepenny Opera is based on John Gay's Beggar's Opera, and Edward II on Marlowe), a sardonic humorist, and a man of rare musical and visual awareness; but he was often bad at creating living characters or at giving his plays tension and shape. As a producer he liked lightness, clarity, and firmly knotted narrative sequence; a perfectionist, he forced the German theatre, against its nature, to underplay. As a theoretician he made principles out of his preferences--and even out of his faults. Until 1924 Brecht lived in Bavaria, where he was born, studied medicine (Munich, 1917-21), and served in an army hospital (1918). From this period date his first play, Baal (produced 1923); his first success, Trommeln in der Nacht (Kleist Preis, 1922; Drums in the Night); the poems and songs collected as Die Hauspostille (1927; A Manual of Piety, 1966), his first professional production (Edward II, 1924); and his admiration for Wedekind, Rimbaud, Villon, and Kipling. During this period he also developed a violently antibourgeois attitude that reflected his generation's deep disappointment in the civilization that had come crashing down at the end of World War I.