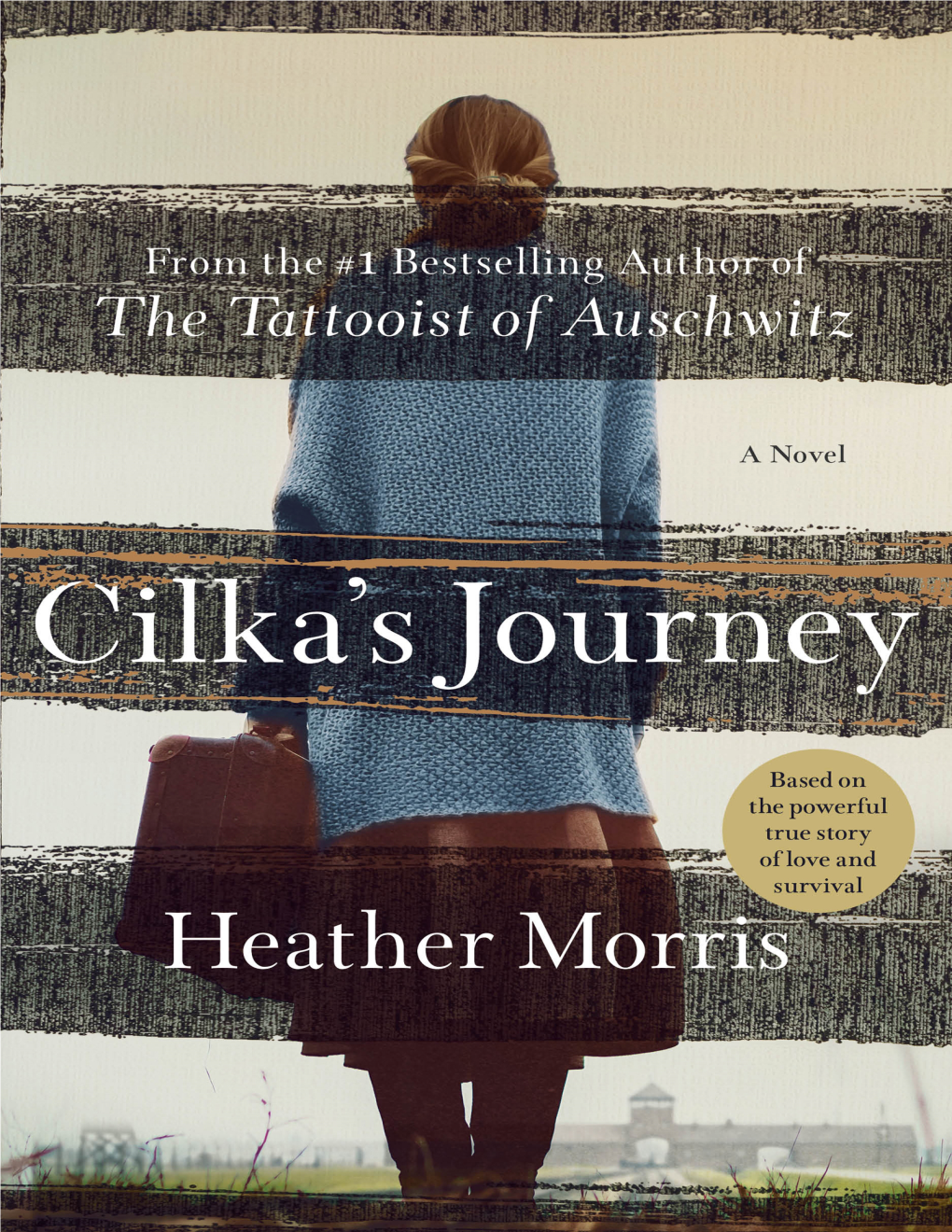

Cilkas Journey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Barents Region Volume 11 N-Y

encyclopedia of The Barents Region volume 11 n-y Editor-in-chief MATS-OLOV OLSSON Co-Editors Fredrick Backman, Alexey Golubev, Björn Norlin, Lars Ohlsson Assistant and Graphics Editor Lars Elenius pax forlag a/s, oslo 2016 © pax forlag 2016 cover illustration vol i: the death of willem barentz, oil on canvas by christiaan julius lodewyck portman (1836). national maritime museum, london. cover photo vol ii: russian prirazlomnaya oil rig in the pechora sea, nenets autonomous okrug, operated by gazprom neft. licensed under cc by-sa 4.0, via wikimedia commons. photo: krichevsky. trykk: printed in isbn 978-82-530-3858-2 (vol 1) isbn 978-82-530-3859-9 (vol ii) isbn 978-82-530-3857-5 (vol 1 and vol ii) isbn 978-82-530-3878-0 (the barents region | encyclopedia of the barents region) Image Editor: Anders Alm Cartographer: David Keeping Language Editors: Pat Shrimpton, Umeå, and Matthew Hogg, Semantix, Umeå Board of Advisers Assoc. Prof. Irina A. Chernyakova Prof. Veli Pekka Lehtola Institute of History, Political and Social Giellagas Institute for Sámi Studies Sciences, Petrozavodsk State University, University of Oulu, Finland Russian Federation Assoc. Prof. Lyubov A. Maksimova Assoc. Prof. Alexander N. Davydov Institute of History and Law, Institute of Ecological Problems of the North Syktyvkar State University, Russian Academy of Sciences, Ural Branch, Russian Federation Arkhangelsk, Russian Federation Assoc. Prof. Jelena Porsanger Prof. Lars-Erik Edlund Sámi University College, Department of Language Studies, Kautokeino, Norway Umeå University, Sweden Prof. Helge Salvesen Prof. Lars Elenius Department of History and Religious Studies, Department of Business Administration, UiT The Arctic University of Norway, Technology and Social Sciences, Tromsø, Norway Luleå University of Technology, Sweden Prof. -

An Organizational Analysis of the Nazi Concentration Camps

Chaos, Coercion, and Organized Resistance; An Organizational Analysis of the Nazi Concentration Camps DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Thomas Vernon Maher Graduate Program in Sociology The Ohio State University 2013 Dissertation Committee: Dr. J. Craig Jenkins, Co-Advisor Dr. Vincent Roscigno, Co-Advisor Dr. Andrew W. Martin Copyright by Thomas V. Maher 2013 Abstract Research on organizations and bureaucracy has focused extensively on issues of efficiency and economic production, but has had surprisingly little to say about power and chaos (see Perrow 1985; Clegg, Courpasson, and Phillips 2006), particularly in regard to decoupling, bureaucracy, or organized resistance. This dissertation adds to our understanding of power and resistance in coercive organizations by conducting an analysis of the Nazi concentration camp system and nineteen concentration camps within it. The concentration camps were highly repressive organizations, but, the fact that they behaved in familiar bureaucratic ways (Bauman 1989; Hilberg 2001) raises several questions; what were the bureaucratic rules and regulations of the camps, and why did they descend into chaos? How did power and coercion vary across camps? Finally, how did varying organizational, cultural and demographic factors link together to enable or deter resistance in the camps? In order address these questions, I draw on data collected from several sources including the Nuremberg trials, published and unpublished prisoner diaries, memoirs, and testimonies, as well as secondary material on the structure of the camp system, individual camp histories, and the resistance organizations within them. My primary sources of data are 249 Holocaust testimonies collected from three archives and content coded based on eight broad categories [arrival, labor, structure, guards, rules, abuse, culture, and resistance]. -

The Pennsylvania State University Schreyer Honors College

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY PRIDE OF THE FATHERLAND: THE IMPACT OF NAZI RACIAL IDEOLOGY ON THE 3. SS TOTENKOPFDIVISION AARON METHENY SPRING 2015 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for baccalaureate degrees in History and Political Science with honors in History Reviewed and approved* by the following: Tobias Brinkmann Malvin and Lea Bank Associate Professor of Jewish Studies and History Thesis Supervisor Michael Milligan Senior Lecturer in History Honors Adviser * Signatures are on file in the Schreyer Honors College. i ABSTRACT One of the more elite military formations in the German Army during the Second World War was the 3. SS Totenkopfdivision. This unit was originally created out of concentration camp guards and acquired a reputation for fanaticism and brutality during its four years of combat on the Eastern Front. Yet because of its unique relationship with the concentration camp system, Nazi racial ideology negatively impacted the performance of Totenkopfdivision in the field. Already heavy casualties were increased because of the willingness of the soldiers to unnecessarily expose themselves to danger as they believed that they were naturally superior to their Soviet counterparts. Losses proved almost impossible to replace as the concentration camp system retained 35,000 men to serve as guards and, despite numerous protests, refused to release them to serve at the front. Nazi racial ideology also interfered with the equipment that Totenkopfdivision needed to function. Germany was forced to rely increasingly on slave labor, but took no steps to ensure the welfare of those laborers. Skilled Jewish laborers were replaced with unskilled non-Jewish laborers because top Nazi officials wanted to eliminate the Jews, causing constant delays to production. -

Dissertation

DISSERTATION Titel der Dissertation “Making a viable city: visions, strategies and practices”. Verfasserin Elena Nuikina, MA angestrebter akademischer Grad Doktorin der Philosophie (Dr.phil.) Wien, 2014 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 784 452 Dissertationsgebiet lt. Studienblatt: Geographie Betreuer: Univ. – Prof. Dr. Heinz Faßmann This manuscript is dedicated to my family. STATEMENT OF ACCESS I, the undersigned author of this work, understand that University of Vienna will make this thesis available for use within the University Library for use elsewhere. I understand that, as an unpublished work, a thesis has significant protection under the Copyright Act and; I do not wish to place any further restriction on access to this work. 17.08.2014 Elena Nuikina STATEMENT OF SOURCES I declare that this thesis is my own work and has not been submitted in any form for another degree or diploma at any university or other institution of tertiary education. Information derived from the published or unpublished work of others has been acknowledged in the text and a list of references is given. 17.08.2014 Elena Nuikina ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Functioning, sustainable and efficient development of urban areas is the principal goal of urban planners, decision-makers and urban economists worldwide. Social characteristics and economic factors that contribute to the well-being of inhabitants are the two explanations of local success. Taking one step farther, this dissertation explores how situatedness of a settlement in the extra-local economic networks and power relations shapes strategies, practices of and views on the city development. The theoretical contribution of the present work to the urban geography is the application of the concept of city viability in conjunction with the concepts of positionality and path dependence to improve our understanding of how the notion city viability is constructed, perceived and implemented in general. -

In the Forge of Stalin of Forge the in Kotljarchuk AUS Andrej Gammalsvenskby Is the Only Swedish Settlement to the East from Finland, Founded in 1782

AUS AndrejAUS Kotljarchuk In the Forge of Stalin Gammalsvenskby is the only Swedish settlement to the east from Finland, founded in 1782. In the past of Gammalsvenskby the history of the Soviet Union, Sweden, Acta Universitatis Stockholmiensis the international communist movement and Nazi Germany combined in a bizar- Stockholms Studies In History, 100 re form. And even when the ploughmen of the Kherson steppes did not left their native village, the great powers themselves visited them with the intention to rule forever. The history of colony is viewed through the prism of the theory of “forced normalization” and the concept of “changes of collective identity“. The author intends to study the techniques of forced normalization and the strategy of the In the Forge of Stalin collective resistance. Swedish Colonists of Ukraine in Totalitarian Experiments Andrej Kotljarchuk is an associate professor in history, working as a university of the Twentieth Century lecturer at the Department of History, Stockholm University; and as a senior rese- archer at the School of Historical and Contemporary Studies, Södertörn University. His research focuses on ethnic minorities and role of experts’ communities, mass Andrej Kotljarchuk Stockholm 2014 violence and the politics of memory. His recent publications include the book chap- ters “The Nordic Threat: Soviet Ethnic Cleansing on the Kola Peninsula” (2014), “The Memory of Roma Holocaust in Ukraine: Mass Graves, Memory Work and the Politics of Commemoration” (2014); as well as the articles “World War II Memory Politics: Jewish, Polish and Roma Minorities of Belarus”, in Journal of Belarusian Studies (2013) and “Kola Sami in the Stalinist terror: a quantitative analysis”, in Journal of Northern Studies (2012). -

Philately and Chemistry

8: Philately and chemistry The Schwitters portrait of Klaus Hinrichsen was one of six 2010 special [ 163 ] issue stamps in the Isle of Man. Among the others are paintings by other internees – Herbert Kaden, Herman Fechenbach, Imre Goth and an artist known as Bertram. The stamp with a cover value of 132p is a 1940 drawing of a violinist in Onchan camp, by the Austrian artist Ernst Eisenmayer. I first saw the Paul Humpoletz, drawing at the Sayle Gallery in Douglas, Isle of Man, in April 2010. The New Year card, Isle of Man internment camp. exhibition, a version of which had originated at the Ben Uri Gallery 1940 in London the previous year, was ‘Forced Journeys: Artists in Exile in Paul Humpoletz Britain c. 1933–45’. For the Douglas show, I had loaned two works on cartoon, Isle of Man internment camp, paper, which had been my father’s and which he had saved from his 1940 year in internment. One was a woodcut by the artist Paul Humpoletz – an image of a Jewish New Year service held in the Palace Theatre, Central Promenade Camp, on 3 October 1940. Later I found another print by Humpoletz in my father’s papers – a cartoon about life in the internment camp. We – my sisters and I – also loaned a drawing of my father, made in Onchan camp in 1940 by an unknown artist. The signature is not legible, and even the expert on Jewish artists in exile, Jutta Vinzent, who has written a book on the subject, could not recognise it. -

Nova Science Publishers, Inc

Nova Science Publishers, Inc. Art Director: Christopher Concannon Graphics: Elenor Kallberg and Maria Ester Hawrys Book Production: Michael Lyons, Roseann Pena, Casey Pfalzer, June Martino, Tammy Sauter, and Michelle Lalo Circulation: Irene Kwartiroff, Annette Hellinger, and Benjamin Fung Library of Congress CataloginginPublication Data Vachnadze, Georgii Nikolaevich Russia’s hotbeds of tension / George N. Vachnadze p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1560721413: $59.00 1. Russia (Federation)—Ethnic relations. 2. RegionalismRussia (Federation). 3. Russia (Federation)Politics and government — 1991 I. Title. DK510.33.V33 1993 9321645 305.8’00947~dc20 CIP © 1994 Nova Science Publishers, Inc. 6080 Jericho Turnpike, Suite 207 Commack, New York 11725 Tele. 5164993103 Fax 5164993146 EMail [email protected] All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means: elec tronic, electrostatic, magnetic, tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without permission from the publishers. Printed in the United States of America TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Russia to follow the path of the USSR 1 PART ONE REGIONS THREATEN MOSCOW WITH DIVORCE URALS. Nuclear Discharges in Kyshtym Equals 24 Chernobyl Accidents 13 SIBERIA. Petrodollars Prolonged the Agony of Communism for 30 Years 25 RUSSIAN NORTH. Genocide: From Stalinist Camps to Nuclear Dumps and Testing Ranges 50 FAR EAST. In One Boat with the Japanese, Koreans, Chinese and Americans 66 PART TWO REPUBLICS WITH LITTLE IN COMMON WITH ORTHODOX CHURCH LEGACY OF COMMUNISTS AND GOLDEN HORDE BASHKORTOSTAN. Overwhelming Catastrophes 77 BURYATIA. Buddhism Revived 84 CHUVASHIA. Famous Dark Beer 90 KARELIA. Ruined Part of Finland 91 KOMI. -

Holocaust and Jewish Resistance Teachers' Program Summer 2018 Documents

Holocaust and Jewish Resistance Teachers’ Program Summer 2018 Documents May 1, 2018 Holocaust and Jewish Resistance Teachers’ Program Copyright © 2017 American Gathering of Holocaust Survivors and Their Descendants PO Box 1922, New York, NY 10156 (212) 239-4230 www.hajrtp.org July 2018 Elaine Culbertson Neil Garfinkle Meryl Menashe Program Director Program Liaison Program Liaison COPYRIGHT NOTICE The Content here is provided under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License (“CCPL” or “license”). This Content is protected by copyright and/or other applicable law. Any use of the Content other than as authorized under this license or copyright law is prohibited. By exercising any rights to the work provided here, you accept and agree to be bound by the terms of this license. To the extent this license may be considered to be a contract, the licensor grants you the rights contained here in consideration of your acceptance of such terms and conditions. Under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License, you are invited to copy, distribute and/or modify the Content, and to use the Content here for personal, educational, and other noncommercial purpose on the following terms: • You must cite the author and source of the Content as you would material from any printed work. • You must also cite and link to, when possible, the website as the source of the Content. • You may not remove any copyright, trademark, or other proprietary notices, including attribution, information, credits, and notices that are placed in or near the Content. • You must comply with all terms or restrictions other than copyright (such as trademark, publicity, and privacy rights, or contractual restrictions) as may be specified in the metadata or as may otherwise apply to the Content. -

CIVIL ACTION : V. : : THEODOR SZEHINSKYJ : NO

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF PENNSYLVANIA UNITED STATES OF AMERICA : CIVIL ACTION : v. : : THEODOR SZEHINSKYJ : NO. 99-5348 MEMORANDUM Dalzell, J. July 24, 2000 The Government has filed this action under Section 340(a) of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 (“INA”), 8 U.S.C. § 1451, asking us to revoke the United States citizenship of defendant Theodor Szehinskyj because of his alleged service as a Waffen SS Death’s Head Battalion concentration camp guard during World War II. After a nonjury trial, this Memorandum will constitute our findings of fact and conclusions of law pursuant to Fed. R. Civ. P. 52(a). Given the gravity of the relief the Government seeks against this 76-year-old citizen, we must consider in extended detail the evidence developed during his five-day trial. Our canvass regrettably but necessarily must include exposition of grisly details of the horrific concentration camp system that was the soul of the Third Reich. I. Background Facts and Claims The Government alleges in its one-count complaint that Szehinskyj served as an armed Nazi concentration camp guard during World War II and therefore was not entitled to the immigrant visa he received under the Displaced Persons Act of 1948 (“DPA”), Pub. L. No. 80-774, ch. 647, 62 Stat. 1009, as amended, June 16, 1950, Pub. L. No. 81-555, 64 Stat. 219. 1 Szehinskyj vigorously disputes these allegations, claiming that he was a slave laborer on a farm belonging to Hildegard Lechner near Schiltern, Austria during the time of his alleged Nazi service. -

Sachsenhausen Concentration Camp from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Coordinates: 52°45′57″N 13°15′51″E

Create account Log in Article Talk Read Edit View history Sachsenhausen concentration camp From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Coordinates: 52°45′57″N 13°15′51″E Sachsenhausen ("Saxon's Houses", German pronunciation: [zaksәnˈhaʊzәn]) or Navigation Sachsenhausen-Oranienburg was a Nazi concentration camp in Oranienburg, Main page Germany, used primarily for political prisoners from 1936 to the end of the Third Reich Contents in May 1945. After World War II, when Oranienburg was in the Soviet Occupation Zone, Featured content the structure was used as an NKVD special camp until 1950 (See NKVD special camp Current events Nr. 7). The remaining buildings and grounds are now open to the public as a museum. Random article Donate to Wikipedia Contents 1 Sachsenhausen under the NSDAP 2 Camp layout Interaction 3 Custody zone Help 4 Prisoner labor Prisoners of Sachsenhausen, 19 December 1938 About Wikipedia 5 Prisoner abuses Community portal 6 Aftermath Recent changes 6.1 Camp commanders Part of a series on Contact Wikipedia 7 Notable inmates and victims during German period The Holocaust 8 The structure under the Soviets Toolbox 9 The Sachsenhausen camp today 10 Gallery What links here 11 See also Related changes 12 Footnotes Upload file 13 References Special pages 14 Further reading Permanent link 15 External links Page information Data item Sachsenhausen under the NSDAP [edit] Cite this page Responsibility The camp was established in 1936. It was located 35 kilometres (22 mi) north of Berlin, which gave Nazi Germany Print/export it a primary position among the German concentration camps: the administrative centre of all People concentration camps was located in Oranienburg, and Sachsenhausen became a training centre Create a book Major perpetrators Adolf Hitler for Schutzstaffel (SS) officers (who would often be sent to oversee other camps afterwards). -

National Socialist Concentration Camps: Legend and Reality JÜRGEN GRAF

National Socialist Concentration Camps: Legend and Reality JÜRGEN GRAF 1. Starting Position On April 11, 1945, American troops entered Buchenwald concentration camp. Four days later, British troops reached Bergen-Belsen concentration camp. In the weeks that followed, the Anglo- Americans liberated other camps, including Dachau (April 29) and Mauthausen (May 5). To the victorious soldiers, all these concentration camps represented scenes of horror. The Jewish historian Walter Laqueur reports in this regard:1 “On April 15, units of a British regi- ment entered Bergen-Belsen concen- tration camp following a ceasefire negotiated with the local German commander. Colonel Taylor, who commanded the regiment, wrote fol- lowing an initial investigation of the camp in the laconic language of an official report: ‘As we walked along the main street of the camp, we were greeted with jubilation by prisoners and saw the condition of the inmates for the first time. Many were little more than liv- ing skeletons. Men and women lay in rows on both sides of the street. Oth- ers crawled slowly and aimlessly around with emaciated, expres- Mass Grave in Bergen-Belsen camp, filled mainly with in- sionless faces.’ mates who had succumbed to a typhus epidemic shortly be- fore the end of World War II or thereafter. Photo taken after Tens of thousands of corpses, many the liberation of the camp by British forces. in advanced stages of decomposition, lay piled on top of each other.” Following the soldiers came a swarm of photographers and journalists; the world was immediately filled with horrifying images of piles of bodies and walking skeletons. -

Holocaust and Jewish Resistance Teachers' Program Summer 2015

Holocaust and Jewish Resistance Teachers’ Program Summer 2015 Documents Holocaust and Jewish Resistance Teachers’ Program American Gathering of Holocaust Survivors and Their Descendants 122 W 30th St #304A New York, NY 10001-4009 (212) 239-4230 www.hajrtp.org July 2015 Elaine Culbertson Neil Garfinkle Meryl Menashe Program Director Program Liaison Program Liaison COPYRIGHT NOTICE The Content here is provided under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License (“CCPL” or “license”). This Content is protected by copyright and/or other applicable law. Any use of the Content other than as authorized under this license or copyright law is prohibited. By exercising any rights to the work provided here, you accept and agree to be bound by the terms of this license. To the extent this license may be considered to be a contract, the licensor grants you the rights contained here in consideration of your acceptance of such terms and conditions. Under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License, you are invited to copy, distribute and/or modify the Content, and to use the Content here for personal, educational, and other noncommercial purpose on the following terms: • You must cite the author and source of the Content as you would material from any printed work. • You must also cite and link to, when possible, the website as the source of the Content. • You may not remove any copyright, trademark, or other proprietary notices, including attribution, information, credits, and notices that are placed in or near the Content. • You must comply with all terms or restrictions other than copyright (such as trademark, publicity, and privacy rights, or contractual restrictions) as may be specified in the metadata or as may otherwise apply to the Content.