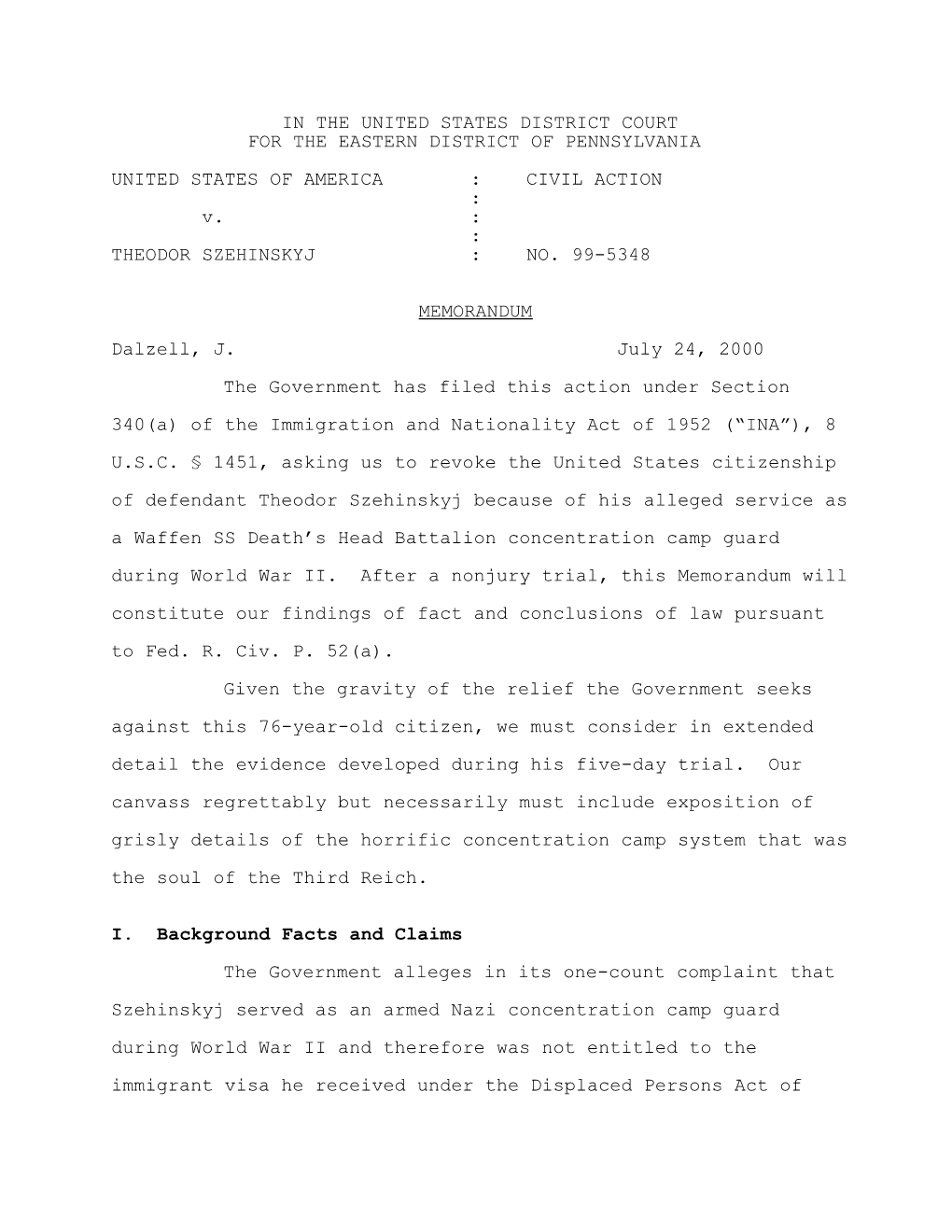

CIVIL ACTION : V. : : THEODOR SZEHINSKYJ : NO

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Complaisance to Collaboration: Analyzing Citizensâ•Ž Motives Near

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Proceedings of the Tenth Annual MadRush MAD-RUSH Undergraduate Research Conference Conference: Best Papers, Spring 2019 From Complaisance to Collaboration: Analyzing Citizens’ Motives Near Concentration and Extermination Camps During the Holocaust Jordan Green Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/madrush Part of the European History Commons, and the Holocaust and Genocide Studies Commons Green, Jordan, "From Complaisance to Collaboration: Analyzing Citizens’ Motives Near Concentration and Extermination Camps During the Holocaust" (2019). MAD-RUSH Undergraduate Research Conference. 1. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/madrush/2019/holocaust/1 This Event is brought to you for free and open access by the Conference Proceedings at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in MAD-RUSH Undergraduate Research Conference by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. From Complaisance to Collaboration: Analyzing Citizens’ Motives Near Concentration and Extermination Camps During the Holocaust Jordan Green History 395 James Madison University Spring 2018 Dr. Michael J. Galgano The Holocaust has raised difficult questions since its end in April 1945 including how could such an atrocity happen and how could ordinary people carry out a policy of extermination against a whole race? To answer these puzzling questions, most historians look inside the Nazi Party to discern the Holocaust’s inner-workings: official decrees and memos against the Jews and other untermenschen1, the role of the SS, and the organization and brutality within concentration and extermination camps. However, a vital question about the Holocaust is missing when examining these criteria: who was watching? Through research, the local inhabitants’ knowledge of a nearby concentration camp, extermination camp or mass shooting site and its purpose was evident and widespread. -

Entwicklung Der Schülerzahlen an Gymnasien Im Landkreis Dachau Stand: 05

Entwicklung der Schülerzahlen an Gymnasien im Landkreis Dachau Stand: 05. Februar 2020 Ansprechpartner: Erstellung durch: LANDRATSAMT DACHAU SAGS - Institut für Sozialplanung, Sachgebiet Kreisschulen und ÖPNV Jugend- und Altenhilfe, Weiherweg 16, 85221 Dachau Gesundheitsforschung und Statistik Postfach 1520, 85205 Dachau Theodor-Heuss-Platz 1 86150 Augsburg Herr Albert Herbst Dipl. Stat. Christian Rindsfüßer Sachgebietsleiter Telefon: 0821/346298-3 Telefon: 08131/74-164 E-Mail: [email protected] E-Mail: [email protected] Quelle: SAGS 2020 Folie 2 Gliederung Folie 1. Ergebnisse der Bevölkerungsprognose 4 2. Analyse der Schülerzahlen im Landkreis Dachau aus Sicht der Gymnasien 8 3. Prognose der Schüler an Gymnasien im Landkreis Dachau 20 4. Simulation des vierten Gymnasiums (Karlsfeld) und eines fünften Gymnasiums (Standort „offen“) im Landkreis Dachau 27 Quelle: SAGS 2020 Folie 3 Ergebnisse der Bevölkerungsprognose Quelle: SAGS 2020 Folie 4 Annahmen zur Bevölkerungsprognose Neben dem Ausgangsbestand (Erhebung zum 01. Oktober 2019 nach Alter und Geschlecht auf Gemeindeebene) gibt es drei Determinanten der Bevölkerungsentwicklung in der Vergangenheit, Gegenwart und Zukunft: • Generatives Verhalten (Fruchtbarkeit, Zahl der Geburten) • Sterblichkeit • Wanderungen • Datengrundlage: Demographiespiegel 2017-2037 des Bayerischen Statistischen Landesamtes. Für die Gemeinden Bergkirchen, Odelzhausen, Pfaffenhofen a.d. Glonn, Sulzemoos wurde die Bevölkerungsvorausberechnung des Statistischen Landesamtes an die bekannten -

HBO and the HOLOCAUST: CONSPIRACY, the HISTORICAL FILM, and PUBLIC HISTORY at WANNSEE Nicholas K. Johnson Submitted to the Facul

HBO AND THE HOLOCAUST: CONSPIRACY, THE HISTORICAL FILM, AND PUBLIC HISTORY AT WANNSEE Nicholas K. Johnson Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in the Department of History, Indiana University December 2016 Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. Master’s Thesis Committee __________________________________ Raymond J. Haberski, Ph.D., Chair __________________________________ Thorsten Carstensen, Ph.D. __________________________________ Kevin Cramer, Ph.D. ii Acknowledgements First, I would like to thank the members of my committee for supporting this project and offering indispensable feedback and criticism. I would especially like to thank my chair, Ray Haberski, for being one of the most encouraging advisers I have ever had the pleasure of working with and for sharing his passion for film and history with me. Thorsten Carstensen provided his fantastic editorial skills and for all the times we met for lunch during my last year at IUPUI. I would like to thank Kevin Cramer for awakening my interest in German history and for all of his support throughout my academic career. Furthermore, I would like to thank Jason M. Kelly, Claudia Grossmann, Anita Morgan, Rebecca K. Shrum, Stephanie Rowe, Modupe Labode, Nancy Robertson, and Philip V. Scarpino for all the ways in which they helped me during my graduate career at IUPUI. I also thank the IUPUI Public History Program for admitting a Germanist into the Program and seeing what would happen. I think the experiment paid off. -

Kristallnacht Caption: Local Residents Watch As Flames Consume The

Kristallnacht Caption: Local residents watch as flames consume the synagogue in Opava, set on fire during Kristallnacht. Description of event: Literally, "Night of Crystal," is often referred to as the "Night of Broken Glass." The name refers to the wave of violent anti-Jewish pogroms which took place throughout Germany, annexed Austria, and in areas of the Sudetenland in Czechoslovakia recently occupied by German troops. Instigated primarily by Nazi Party officials and members of the SA (Sturmabteilungen: literally Assault Detachments, but commonly known as Storm Troopers) and Hitler Youth, Kristallnacht owes its name to the shards of shattered glass that lined German streets in the wake of the pogrom- broken glass from the windows of synagogues, homes, and Jewish-owned businesses plundered and destroyed during the violence. Nuremberg Laws Caption: A young baby lies on a park bench marked with a J to indicate it is only for Jews. Description of event: Antisemitism and the persecution of Jews represented a central tenet of Nazi ideology. In their 25-point Party Program, published in 1920, Nazi party members publicly declared their intention to segregate Jews from "Aryan" society and to abrogate Jews' political, legal, and civil rights.Nazi leaders began to make good on their pledge to persecute German Jews soon after their assumption of power. During the first six years of Hitler's dictatorship, from 1933 until the outbreak of war in 1939, Jews felt the effects of more than 400 decrees and regulations that restricted all aspects of their public and private lives. Many of those laws were national ones that had been issued by the German administration and affected all Jews. -

SS-Totenkopfverbände from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia (Redirected from SS-Totenkopfverbande)

Create account Log in Article Talk Read Edit View history SS-Totenkopfverbände From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia (Redirected from SS-Totenkopfverbande) Navigation Not to be confused with 3rd SS Division Totenkopf, the Waffen-SS fighting unit. Main page This article may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. No cleanup reason Contents has been specified. Please help improve this article if you can. (December 2010) Featured content Current events This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding Random article citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (September 2010) Donate to Wikipedia [2] SS-Totenkopfverbände (SS-TV), rendered in English as "Death's-Head Units" (literally SS-TV meaning "Skull Units"), was the SS organization responsible for administering the Nazi SS-Totenkopfverbände Interaction concentration camps for the Third Reich. Help The SS-TV was an independent unit within the SS with its own ranks and command About Wikipedia structure. It ran the camps throughout Germany, such as Dachau, Bergen-Belsen and Community portal Buchenwald; in Nazi-occupied Europe, it ran Auschwitz in German occupied Poland and Recent changes Mauthausen in Austria as well as numerous other concentration and death camps. The Contact Wikipedia death camps' primary function was genocide and included Treblinka, Bełżec extermination camp and Sobibor. It was responsible for facilitating what was called the Final Solution, Totenkopf (Death's head) collar insignia, 13th Standarte known since as the Holocaust, in collaboration with the Reich Main Security Office[3] and the Toolbox of the SS-Totenkopfverbände SS Economic and Administrative Main Office or WVHA. -

3868546065 Lp.Pdf

Studien zur Gewaltgeschichte des 20. Jahrhunderts Ausgewählt von Jörg Baberowski, Bernd Greiner und Michael Wildt Das 20. Jahrhundert gilt als das Jahrhundert des Genozids, der Lager, des Totalen Krieges, des Totalitarismus und Ter- rorismus, von Flucht, Vertreibung und Staatsterror – ge- rade weil sie im Einzelnen allesamt zutreffen, hinterlassen diese Charakterisierungen in ihrer Summe eine eigentüm- liche Ratlosigkeit. Zumindest spiegeln sie eine nachhaltige Desillusionierung. Die Vorstellung, Gewalt einhegen, be- grenzen und letztlich überwinden zu können, ist der Ein- sicht gewichen, dass alles möglich ist, jederzeit und an jedem Ort der Welt. Und dass selbst Demokratien, die Erben der Aufklärung, vor entgrenzter Gewalt nicht gefeit sind. Das normative und ethische Bemühen, die Gewalt einzugrenzen, mag vor diesem Hintergrund ungenügend und mitunter sogar vergeblich erscheinen. Hinfällig ist es aber keineswegs, es sei denn um den Preis der moralischen Selbstaufgabe. Ausgewählt von drei namhaften Historikern – Jörg Baberowski, Bernd Greiner und Michael Wildt –, präsen- tieren die »Studien zur Gewaltgeschichte des 20. Jahrhun- derts« die Forschungsergebnisse junger Wissenschaftle- rinnen und Wissenschaftler. Die Monografien analysieren am Beispiel von totalitären Systemen wie dem National- sozialismus und Stalinismus, von Diktaturen, Autokratien und nicht zuletzt auch von Demokratien die Dynamik ge- walttätiger Situationen, sie beschreiben das Erbe der Ge- walt und skizzieren mögliche Wege aus der Gewalt. Sara Berger Experten der Vernichtung -

Bevölkerungsprognose Für Den Landkreis Straubing-Bogen Unter Besonderer Berücksichtigung Jugend- Und Altenhilferelevanter Fragestellungen

Bevölkerungsprognose für den Landkreis Straubing-Bogen unter besonderer Berücksichtigung jugend- und altenhilferelevanter Fragestellungen Augsburg, im Oktober 2020 Herausgeber: Landratsamt Straubing-Bogen Amt für Jugend und Familie Leutnerstraße 15 94315 Straubing Ansprechpartnerin: Mara Wenzinger | Jugendhilfeplanung Telefon: 09421 / 973 305 E-Mail: [email protected] www.landkreis-straubing-bogen.de Zusammenstellung und Bearbeitung durch: Diplom-Statistiker Christian Rindsfüßer, SAGS Institut für Jugend- und Altenhilfeplanung, Jugend- und Altenhilfe, Gesundheitsforschung und Statistik Dipl. Stat. Christian Rindsfüßer Theodor-Heuss-Platz 1 86150 Augsburg Telefon: 0821 3462 98-0 Fax: 0821 / 3462 98-8 E-Mail: [email protected] Homepage: www.sags-consult.de Bevölkerungsprognose Ausgangslage Gliederung Vorwort ............................................................................................................... 5 1. Die wichtigsten Ergebnisse vorneweg ........................................................................... 7 2. Ausgangslage ............................................................................................................. 10 3. Geburten- und Wanderungsanalyse ............................................................................ 16 4. Allgemeine Ergebnisse der Bevölkerungsprognose für den Landkreis Straubing-Bogen 24 4.1 Entwicklung der Gesamtbevölkerung ................................................................... 24 4.2 Entwicklung einzelner Altersgruppen -

Nurses and Midwives in Nazi Germany

Downloaded by [New York University] at 03:18 04 October 2016 Nurses and Midwives in Nazi Germany This book is about the ethics of nursing and midwifery, and how these were abrogated during the Nazi era. Nurses and midwives actively killed their patients, many of whom were disabled children and infants and patients with mental (and other) illnesses or intellectual disabilities. The book gives the facts as well as theoretical perspectives as a lens through which these crimes can be viewed. It also provides a way to teach this history to nursing and midwifery students, and, for the first time, explains the role of one of the world’s most historically prominent midwifery leaders in the Nazi crimes. Downloaded by [New York University] at 03:18 04 October 2016 Susan Benedict is Professor of Nursing, Director of Global Health, and Co- Director of the Campus-Wide Ethics Program at the University of Texas Health Science Center School of Nursing in Houston. Linda Shields is Professor of Nursing—Tropical Health at James Cook Uni- versity, Townsville, Queensland, and Honorary Professor, School of Medi- cine, The University of Queensland. Routledge Studies in Modern European History 1 Facing Fascism 9 The Russian Revolution of 1905 The Conservative Party and the Centenary Perspectives European dictators 1935–1940 Edited by Anthony Heywood and Nick Crowson Jonathan D. Smele 2 French Foreign and Defence 10 Weimar Cities Policy, 1918–1940 The Challenge of Urban The Decline and Fall of a Great Modernity in Germany Power John Bingham Edited by Robert Boyce 11 The Nazi Party and the German 3 Britain and the Problem of Foreign Office International Disarmament Hans-Adolf Jacobsen and Arthur 1919–1934 L. -

Freising Gate

Freising Gate History... ... and a story In 1391, the Bavarian dukes Stephan III and During the Thirty Years’ War, the gate was so Johann II granted Dachau the right to hold tightly guarded that in 1648, Dachau residents annual fairs. This meant looking after security in living outside the gate complained that the gate the town. The town was surrounded by a wall was locked so early that they could not enter and moat and a palisade. In the south, the River the town at any time to relieve themselves. Amper and the steep slope of the hill provided natural protection. Here, people and goods were checked at the “Munich Gate” on Kühberg (now Karlsberg). Funding for a wall was only available for short stretches on either side of the “Augsburg Gate”. This was where the road from Munich left the town in a north-westerly direc- tion. On the road to Freising in the north-east, the “Freising Gate” was erected, which at times was also known as the Lower Gate, Etzenhausen Gate or Altenmarkt Gate. In the 17th century, it provided accommodation for shepherds. The town clerk lived in the gate- Michael Neher (1798–1876): The “Freising Gate” on house. The guard room had two windows and the former Rossmarkt (horse market), pencil drawing, was furnished with a chair, three plank beds, c. 1850, Dachau District Museum and a stove. In the latter half of the century, the gate and neighbouring gatehouse were under- pinned. Records from those days also make mention of the Pruggen (bridge) carrying the road to Etzenhausen and on to Freising over the outer moat. -

Appendix 1: Sample Docum Ents

APPENDIX 1: SAMPLE DOCUMENTS Figure 1.1. Arrest warrant (Haftbefehl) for Georg von Sauberzweig, signed by Morgen. Courtesy of Bundesarchiv Berlin-Lichterfelde 129 130 Appendix 1 Figure 1.2. Judgment against Sauberzweig. Courtesy of Bundesarchiv Berlin-Lichterfelde Appendix 1 131 Figure 1.3. Hitler’s rejection of Sauberzweig’s appeal. Courtesy of Bundesarchiv Berlin-Lichterfelde 132 Appendix 1 Figure 1.4. Confi rmation of Sauberzweig’s execution. Courtesy of Bundesarchiv Berlin- Lichterfelde Appendix 1 133 Figure 1.5. Letter from Morgen to Maria Wachter. Estate of Konrad Morgen, courtesy of the Fritz Bauer Institut APPENDIX 2: PHOTOS Figure 2.1. Konrad Morgen 1938. Estate of Konrad Morgen, courtesy of the Fritz Bauer Institut 134 Appendix 2 135 Figure 2.2. Konrad Morgen in his SS uniform. Estate of Konrad Morgen, courtesy of the Fritz Bauer Institut 136 Appendix 2 Figure 2.3. Karl Otto Koch. Courtesy of the US National Archives Appendix 2 137 Figure 2.4. Karl and Ilse Koch with their son, at Buchwald. Corbis Images Figure 2.5. Odilo Globocnik 138 Appendix 2 Figure 2.6. Hermann Fegelein. Courtesy of Yad Vashem Figure 2.7. Ilse Koch. Courtesy of Yad Vashem Appendix 2 139 Figure 2.8. Waldemar Hoven. Courtesy of Yad Vashem Figure 2.9. Christian Wirth. Courtesy of Yad Vashem 140 Appendix 2 Figure 2.10. Jaroslawa Mirowska. Private collection NOTES Preface 1. The execution of Karl Otto Koch, former commandant of Buchenwald, is well documented. The execution of Hermann Florstedt, former commandant of Majdanek, is disputed by a member of his family (Lindner (1997)). -

History of Nazi Dental Gold: from Dead Bodies Till Swiss Bank

SAJ Forensic Science Volume 1 | Issue 1 www.scholarena.com Research Article Open Access History of Nazi Dental Gold: From Dead Bodies till Swiss Bank Riaud X* Doctor in Dental Surgery, PhD in History of Sciences and Techniques, Winner and Associate Member of the National Academy of Dental Surgery, Member of the National Academy of Surgery, France *Corresponding author: Riaud X, Doctor in Dental Surgery, PhD., in History of Sciences and Techniques, Winner [email protected] and Associate Member of the National Academy of Dental Surgery, Member of the National Academy of Surgery, 145,Citation: route de Vannes, 44800 Saint Herblain, France, Tel: 0033240766488, E-mail: A R T I C RiaudL E I XN (2015) F O History of NaziA DentalB S T Gold: R A CFrom T Dead Bodies till Swiss Bank. SAJ Forensic Sci 1: 105 Article history: The SS Reichsfürher Heinrich Himmler, on the 23rd of September 1940 gave the Received: 02 May 2015 SS doctors orders to collect the golden teeth in the mouth of the dead. Everybody knows that. But, who Accepted: 27 May 2015 knows who were the SS dentists directly implicated in that collection, the real Published: 29 May 2015 figures, how Nazis proceeded? Here are the answers. For the first time. Keywords: History; Dentistry; WWII; Dental gold Introduction rd of September 1940 gave the SS doctors orders to collect the golden teeth in the mouth of the dead, and also “the golden teeth that cannot be repaired”, from the mouth of the people alive. This decree,- The SS that Reichsfürher was part of Heinrich the T4 Operation, Himmler, onwas the not 23 systematically put into practice on the concentration camps prisoners. -

White Supremacy Search Trends in the United States

01 / WHITE SUPREMACY SEARCH TRENDS IN THE UNITED STATES White Supremacy Search Trends in the United States June 2021 02 / WHITE SUPREMACY SEARCH TRENDS IN THE UNITED STATES ! Warning This report contains racist and violent extremist language and other content that readers may find distressing. 03 / WHITE SUPREMACY SEARCH TRENDS IN THE UNITED STATES Contents 04 Introduction 05-06 Crisis Response 07-16 Search Insights 07-09 What Did Americans Search For? 10-11 Where Did Americans Consume Extremist Content? 12 What Were the Most Popular Forums and Websites? 13 What Extremist Literature Did Americans Search For? 14 What Extremist Merchandise Did Americans Search For? 14-15 What Extremist Groups Did Americans Search For? 16 Who Searched for Extremist Content? 17-20 Appendix A: Keyword Descriptions 04 / WHITE SUPREMACY SEARCH TRENDS IN THE UNITED STATES Introduction Moonshot partnered with the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) to analyze US search traffic in July 2020 in response to the threats posed by white supremacist narratives and ideology in the US this past year. The dominant socio-political events of 2020-2021—the COVID-19 pandemic, the widespread BLM protests and counter-protests, and the presidential election—coalesced to create fertile ground for white supremacists and other violent extremist movements to mobilize and recruit. In 2020, racism and systemic racial inequality took center stage in the American public eye, with nationwide mass protests against recent police killings of Black people and historic evidence of racial injustice.1