The Pennsylvania State University Schreyer Honors College

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Complaisance to Collaboration: Analyzing Citizensâ•Ž Motives Near

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Proceedings of the Tenth Annual MadRush MAD-RUSH Undergraduate Research Conference Conference: Best Papers, Spring 2019 From Complaisance to Collaboration: Analyzing Citizens’ Motives Near Concentration and Extermination Camps During the Holocaust Jordan Green Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/madrush Part of the European History Commons, and the Holocaust and Genocide Studies Commons Green, Jordan, "From Complaisance to Collaboration: Analyzing Citizens’ Motives Near Concentration and Extermination Camps During the Holocaust" (2019). MAD-RUSH Undergraduate Research Conference. 1. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/madrush/2019/holocaust/1 This Event is brought to you for free and open access by the Conference Proceedings at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in MAD-RUSH Undergraduate Research Conference by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. From Complaisance to Collaboration: Analyzing Citizens’ Motives Near Concentration and Extermination Camps During the Holocaust Jordan Green History 395 James Madison University Spring 2018 Dr. Michael J. Galgano The Holocaust has raised difficult questions since its end in April 1945 including how could such an atrocity happen and how could ordinary people carry out a policy of extermination against a whole race? To answer these puzzling questions, most historians look inside the Nazi Party to discern the Holocaust’s inner-workings: official decrees and memos against the Jews and other untermenschen1, the role of the SS, and the organization and brutality within concentration and extermination camps. However, a vital question about the Holocaust is missing when examining these criteria: who was watching? Through research, the local inhabitants’ knowledge of a nearby concentration camp, extermination camp or mass shooting site and its purpose was evident and widespread. -

Steven H. Newton KURSK the GERMAN VIEW

TRANSLATED, EDITED, AND ANNOTATED WITH NEW MATERIAL BY Steven H. Newton KURSK THE GERMAN VIEW Eyewitness Reports of Operation Citadel by the German Commanders Translated, edited, and annotated by Steven H. Newton DA CAPO PRESS A Member of the Perseus Books Group Copyright © 2002 by Steven H. Newton All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Printed in the United States of America. Designed by Brent Wilcox Cataloging-in-Publication data for this book is available from the Library of Congress. ISBN 0-306-81150-2 Published by Da Capo Press A Member of the Perseus Books Group http://www.dacapopress.com Da Capo Press books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the U.S. by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 11 Cambridge Center, Cambridge, MA 02142, or call (617) 252-5298. 12345678 9—05 04 03 02 CONTENTS Acknowledgments ix Introduction xi PART 1 Strategic Analysis of Operation Citadel Eyewitness Accounts by German Commanders 1 Operation Citadel Overview by General of Infantry Theodor Busse APPENDIX 1A German Military Intelligence and Soviet Strength, July 1943 27 Armeeabteilung Kempf 29 by Colonel General Erhard Raus APPENDIX 2A Order of Battle: Corps Raus (Special Employment), 2 March 1943 58 APPENDIX -

Introduction to the Captured German Records at the National Archives

THE KNOW YOUR RECORDS PROGRAM consists of free events with up-to-date information about our holdings. Events offer opportunities for you to learn about the National Archives’ records through ongoing lectures, monthly genealogy programs, and the annual genealogy fair. Additional resources include online reference reports for genealogical research, and the newsletter Researcher News. www.archives.gov/calendar/know-your-records The National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) is the nation's record keeper. Of all the documents and materials created in the course of business conducted by the United States Federal government, only 1%–3% are determined permanently valuable. Those valuable records are preserved and are available to you, whether you want to see if they contain clues about your family’s history, need to prove a veteran’s military service, or are researching an historical topic that interests you. www.archives.gov/calendar/know-your-records December 14, 2016 Rachael Salyer Rachael Salyer, archivist, discusses records from Record Group 242, the National Archives Collection of Foreign Records Seized, and offers strategies for starting your historical or genealogical research using the Captured German Records. www.archives.gov/calendar/know-your-records Rachael is currently an archivist in the Textual Processing unit at the National Archives in College Park, MD. In addition, she assists the Reference unit respond to inquiries about World War II and Captured German records. Her career with us started in the Textual Research Room. Before coming to the National Archives, Rachael worked primarily as a professor of German at Clark University in Worcester, MA and a professor of English at American International College in Springfield, MA. -

SS-Totenkopfverbände from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia (Redirected from SS-Totenkopfverbande)

Create account Log in Article Talk Read Edit View history SS-Totenkopfverbände From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia (Redirected from SS-Totenkopfverbande) Navigation Not to be confused with 3rd SS Division Totenkopf, the Waffen-SS fighting unit. Main page This article may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. No cleanup reason Contents has been specified. Please help improve this article if you can. (December 2010) Featured content Current events This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding Random article citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (September 2010) Donate to Wikipedia [2] SS-Totenkopfverbände (SS-TV), rendered in English as "Death's-Head Units" (literally SS-TV meaning "Skull Units"), was the SS organization responsible for administering the Nazi SS-Totenkopfverbände Interaction concentration camps for the Third Reich. Help The SS-TV was an independent unit within the SS with its own ranks and command About Wikipedia structure. It ran the camps throughout Germany, such as Dachau, Bergen-Belsen and Community portal Buchenwald; in Nazi-occupied Europe, it ran Auschwitz in German occupied Poland and Recent changes Mauthausen in Austria as well as numerous other concentration and death camps. The Contact Wikipedia death camps' primary function was genocide and included Treblinka, Bełżec extermination camp and Sobibor. It was responsible for facilitating what was called the Final Solution, Totenkopf (Death's head) collar insignia, 13th Standarte known since as the Holocaust, in collaboration with the Reich Main Security Office[3] and the Toolbox of the SS-Totenkopfverbände SS Economic and Administrative Main Office or WVHA. -

German Jewish Refugees in the United States and Relationships to Germany, 1938-1988

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO “Germany on Their Minds”? German Jewish Refugees in the United States and Relationships to Germany, 1938-1988 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History by Anne Clara Schenderlein Committee in charge: Professor Frank Biess, Co-Chair Professor Deborah Hertz, Co-Chair Professor Luis Alvarez Professor Hasia Diner Professor Amelia Glaser Professor Patrick H. Patterson 2014 Copyright Anne Clara Schenderlein, 2014 All rights reserved. The Dissertation of Anne Clara Schenderlein is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically. _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ Co-Chair _____________________________________________________________________ Co-Chair University of California, San Diego 2014 iii Dedication To my Mother and the Memory of my Father iv Table of Contents Signature Page ..................................................................................................................iii Dedication ..........................................................................................................................iv Table of Contents ...............................................................................................................v -

Guides to German Records Microfilmed at Alexandria, Va

GUIDES TO GERMAN RECORDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXANDRIA, VA. No. 32. Records of the Reich Leader of the SS and Chief of the German Police (Part I) The National Archives National Archives and Records Service General Services Administration Washington: 1961 This finding aid has been prepared by the National Archives as part of its program of facilitating the use of records in its custody. The microfilm described in this guide may be consulted at the National Archives, where it is identified as RG 242, Microfilm Publication T175. To order microfilm, write to the Publications Sales Branch (NEPS), National Archives and Records Service (GSA), Washington, DC 20408. Some of the papers reproduced on the microfilm referred to in this and other guides of the same series may have been of private origin. The fact of their seizure is not believed to divest their original owners of any literary property rights in them. Anyone, therefore, who publishes them in whole or in part without permission of their authors may be held liable for infringement of such literary property rights. Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 58-9982 AMERICA! HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION COMMITTEE fOR THE STUDY OP WAR DOCUMENTS GUIDES TO GERMAN RECOBDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXAM)RIA, VA. No* 32» Records of the Reich Leader of the SS aad Chief of the German Police (HeiehsMhrer SS und Chef der Deutschen Polizei) 1) THE AMERICAN HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION (AHA) COMMITTEE FOR THE STUDY OF WAE DOCUMENTS GUIDES TO GERMAN RECORDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXANDRIA, VA* This is part of a series of Guides prepared -

Nazi Concentration Camp Guard Service Equals "Good Moral Character"?: United States V

American University International Law Review Volume 12 | Issue 1 Article 3 1997 Nazi Concentration Camp Guard Service Equals "Good Moral Character"?: United States v. Lindert K. Lesli Ligomer Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/auilr Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Ligorner, K. Lesli. "Nazi Concentration Camp Guard Service Equals "Good Moral Character"?: United States v. Lindert." American University International Law Review 12, no. 1 (1997): 145-193. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington College of Law Journals & Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in American University International Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NAZI CONCENTRATION CAMP GUARD SERVICE EQUALS "GOODMORAL CHARACTER"?: UNITED STATES V. LINDERT By K Lesli Ligorner Fetching the newspaper from your porch, you look up and wave at your elderly neighbor across the street. This quiet man emigrated to the United States from Europe in the 1950s. Upon scanning the newspaper, you discover his picture on the front page and a story revealing that he guarded a notorious Nazi concen- tration camp. How would you react if you knew that this neighbor became a natu- ralized citizen in 1962 and that naturalization requires "good moral character"? The systematic persecution and destruction of innocent peoples from 1933 until 1945 remains a dark chapter in the annals of twentieth century history. Though the War Crimes Trials at Nilnberg' occurred over fifty years ago, the search for those who participated in Nazi-sponsored persecution has not ended. -

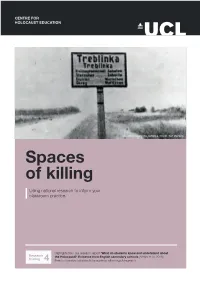

Spaces of Killing Using National Research to Inform Your Classroom Practice

CENTRE FOR HOLOCAUST EDUCATION The entrance sign to Treblinka. Credit: Yad Vashem Spaces of killing Using national research to inform your classroom practice. Highlights from our research report ‘What do students know and understand about Research the Holocaust?’ Evidence from English secondary schools (Foster et al, 2016) briefing 4 Free to download at www.holocausteducation.org.uk/research If students are to understand the significance of the Holocaust and the full enormity of its scope and scale, they need to appreciate that it was a continent-wide genocide. Why does this matter? The perpetrators ultimately sought to kill every Jew, everywhere they could reach them with victims Knowledge of the ‘spaces of killing’ is crucial to an understanding of the uprooted from communities across Europe. It is therefore crucial to know about the geography of the Holocaust. If students do not appreciate the scale of the killings outside of Holocaust relating to the development of the concentration camp system; the location, role and purpose Germany and particularly the East, then it is impossible to grasp the devastation of the ghettos; where and when Nazi killing squads committed mass shootings; and the evolution of the of Jewish communities in Europe or the destruction of diverse and vibrant death camps. cultures that had developed over centuries. This briefing, the fourth in our series, explores students’ knowledge and understanding of these key Entire communities lost issues, drawing on survey research and focus group interviews with more than 8,000 11 to 18 year olds. Thousands of small towns and villages in Poland, Ukraine, Crimea, the Baltic states and Russia, which had a majority Jewish population before the war, are now home to not a single Jewish person. -

The Perpetrators of the November 1938 Pogrom Through German-Jewish Eyes

Chapter 4 The Perpetrators of the November 1938 Pogrom through German-Jewish Eyes Alan E. Steinweis The November 1938 pogrom, often referred to as the “Kristallnacht,” was the largest and most significant instance of organized anti-Jewish violence in Nazi Germany before the Second World War.1 In addition to the massive destruc- tion of synagogues and property, the pogrom involved the physical abuse and terrorizing of German Jews on a massive scale. German police reported an official death toll of 91, but the actual number of Jews killed was probably about ten times that many when one includes fatalities among Jews who were treated brutally during their arrest and subsequent imprisonment in Dachau, Buchenwald, and Sachsenhausen.2 Violence had been a normal feature of the Nazi regime’s anti-Jewish measures since 1933,3 but the scale and intensity of the Kristallnacht were unprecedented. The pogrom occurred less than one year before the outbreak of the war and the first atrocities by the Wehrmacht against Polish Jews, and less than three years before the Einsatzgruppen, Order Police, and other units began to undertake the mass murder of Jews in the Soviet Union. Knowledge about the perpetrators of the pogrom, therefore, pro- vides important context for understanding the violence that came later. To be sure, nobody has yet undertaken the extremely ambitious project to identify precisely which perpetrators of the Kristallnacht eventually would participate directly in the “Final Solution.” There certainly were many such cases, however, perhaps the most notable being Odilo Globocnik, who presided over the po- grom violence in Vienna in November 1938 and less than three years later was placed in charge of Operation Reinhardt, the mass murder of the Jews in the General Government.4 1 Many of the observations in this chapter are based on cases described and documented in the author’s book, Kristallnacht 1938 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009). -

The Waffen-SS in Allied Hands Volume Two

The Waffen-SS in Allied Hands Volume Two The Waffen-SS in Allied Hands Volume Two: Personal Accounts from Hitler’s Elite Soldiers By Terry Goldsworthy The Waffen-SS in Allied Hands Volume Two: Personal Accounts from Hitler’s Elite Soldiers By Terry Goldsworthy This book first published 2018 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2018 by Terry Goldsworthy All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-0858-7 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-0858-3 All photographs courtesy of the US National Archives (NARA), Bundesarchiv and the Imperial War Museum. Cover photo – An SS-Panzergrenadier advances during the Ardennes Offensive, 1944. (German military photo, captured by U.S. military photo no. HD-SN-99-02729; NARA file no. 111-SC-197561). For Mandy, Hayley and Liam. CONTENTS Preface ...................................................................................................... xiii VOLUME ONE Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 The rationale for the study of the Waffen-SS ........................................ 1 Sources of information for this book .................................................... -

Holocaust Documents

The Holocaust The Holocaust is a period in European history that took place in Nazi Germany during the late 1930s and 1940s, just prior to and during World War II. It is important for all people to have an understanding of this genocide. This packet contains a large amount of primary and secondary source information. You should familiarize yourself with this for our discussion. My expectations for this 45 minute Harkness Table are high. I want to hear evidence of your reading and understanding of what happened in the holocaust. This packet is yours to keep. Feel free to mark it up. You may consider using a highlighter; post it notes, something to organize your research and studying so you may be able to hold an intellectual and informed discussion. Additionally, on the day you are not participating in the circle you will need to be contributing to the Google back channel discussion. Please bring your electronic device, phone, tablet, and laptop, whatever you have, to the class. I will be looking for your active engagement in the virtual discussion outside the circle. To view a timeline of the events that you are studying please visit the following webpage: http://www.historyplace.com/worldwar2/holocaust/timeline.html To view images of the Holocaust and German occupation please visit the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum at the following link: http://www.ushmm.org/wlc/en/media_list.php?MediaType=ph Some thoughts and questions to consider when you are preparing: • Who were the Nazis? • What did they stand for? • When did they take control in Germany? • Who was Adolph Hitler? • Who was responsible for the destruction of millions of Jews, Poles, Gypsies, and other groups during World War II? • How could this happen? • Why didn’t the allies do anything to stop it? The Wannsee Protocols On January 20, 1942, an extraordinary 90-minute meeting took place in a lakeside villa in the wealthy Wannsee district of Berlin. -

Alternative Assignments.Pdf

The Holocaust QUESTIONNAIRE - Page 4 7. You are now standing on the outside on a cold and bitter morning, listening for the sound of a truck that will take you to an extermination camp for certain death because you have not asked for mercy and none has been given. After standing about fifteen minutes you hear the sound of a truck approaching and you know what that means. Suddenly, and without even being aware of it, you begin to concentrate hard on not being sent to an extermination camp because you want to live and someday return home again. As you are concentrating you become aware that the person in charge of the camp is walking in your direction. He stops right in front of you and, without saying a word, motions his right hand, signaling you to get back to the work group. You cannot understand why he is doing this when he seemed so determined that you should be sent to an extermination camp. Now your spirits are uplifted again because as long as you can remain in a work group there is hope of surviving this ordeal. Do you believe that your own mental concentration caused it to happen? 8. After staying in a work group for about six weeks, the person in charge of the camp changes his mind and orders that you be shipped out to an extermination camp. This time you begin to accept death as inevitable because you can no longer remain in a work group. You are taken to a railroad station and ordered to enter an open type freight car with about 150 others who are no longer able to perform the heavy physical work.