Translating Pasteur to the Maghreb

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

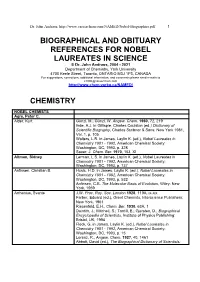

Biographical References for Nobel Laureates

Dr. John Andraos, http://www.careerchem.com/NAMED/Nobel-Biographies.pdf 1 BIOGRAPHICAL AND OBITUARY REFERENCES FOR NOBEL LAUREATES IN SCIENCE © Dr. John Andraos, 2004 - 2021 Department of Chemistry, York University 4700 Keele Street, Toronto, ONTARIO M3J 1P3, CANADA For suggestions, corrections, additional information, and comments please send e-mails to [email protected] http://www.chem.yorku.ca/NAMED/ CHEMISTRY NOBEL CHEMISTS Agre, Peter C. Alder, Kurt Günzl, M.; Günzl, W. Angew. Chem. 1960, 72, 219 Ihde, A.J. in Gillispie, Charles Coulston (ed.) Dictionary of Scientific Biography, Charles Scribner & Sons: New York 1981, Vol. 1, p. 105 Walters, L.R. in James, Laylin K. (ed.), Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 1901 - 1992, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1993, p. 328 Sauer, J. Chem. Ber. 1970, 103, XI Altman, Sidney Lerman, L.S. in James, Laylin K. (ed.), Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 1901 - 1992, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1993, p. 737 Anfinsen, Christian B. Husic, H.D. in James, Laylin K. (ed.), Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 1901 - 1992, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1993, p. 532 Anfinsen, C.B. The Molecular Basis of Evolution, Wiley: New York, 1959 Arrhenius, Svante J.W. Proc. Roy. Soc. London 1928, 119A, ix-xix Farber, Eduard (ed.), Great Chemists, Interscience Publishers: New York, 1961 Riesenfeld, E.H., Chem. Ber. 1930, 63A, 1 Daintith, J.; Mitchell, S.; Tootill, E.; Gjersten, D., Biographical Encyclopedia of Scientists, Institute of Physics Publishing: Bristol, UK, 1994 Fleck, G. in James, Laylin K. (ed.), Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 1901 - 1992, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1993, p. 15 Lorenz, R., Angew. -

Nobel Prizes in Physiology Or Medicine with an Emphasis on Bacteriology

J Med Bacteriol. Vol. 8, No. 3, 4 (2019): pp.49-57 jmb.tums.ac.ir Journal of Medical Bacteriology Nobel Prizes in Physiology or Medicine with an Emphasis on Bacteriology 1 1 2 Hamid Hakimi , Ebrahim Rezazadeh Zarandi , Siavash Assar , Omid Rezahosseini 3, Sepideh Assar 4, Roya Sadr-Mohammadi 5, Sahar Assar 6, Shokrollah Assar 7* 1 Department of Microbiology, Medical School, Rafsanjan University of Medical Sciences, Rafsanjan, Iran. 2 Department of Anesthesiology, Medical School, Kerman University of Medical Sciences, Kerman, Iran. 3 Department of Infectious and Tropical Diseases, Imam Khomeini Hospital Complex, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. 4 Department of Pathology, Dental School, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran. 5 Dental School, Rafsanjan University of Medical Sciences, Rafsanjan, Iran. 6 Dental School, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran. 7 Department of Microbiology and Immunology of Infectious Diseases Research Center, Research Institute of Basic Medical Sciences, Rafsanjan University of Medical Sciences, Rafsanjan, Iran. ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article type: Background: Knowledge is an ocean without bound or shore, the seeker of knowledge is (like) the Review Article diver in those seas. Even if his life is a thousand years, he will never stop searching. This is the result Article history: of reflection in the book of development. Human beings are free and, to some extent, have the right to Received: 02 Feb 2019 choose, on the other hand, they are spiritually oriented and innovative, and for this reason, the new Revised: 28 Mar 2019 discovery and creativity are felt. This characteristic, which is in the nature of human beings, can be a Accepted: 06 May 2019 motive for the revision of life and its tools and products. -

Balcomk41251.Pdf (558.9Kb)

Copyright by Karen Suzanne Balcom 2005 The Dissertation Committee for Karen Suzanne Balcom Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Discovery and Information Use Patterns of Nobel Laureates in Physiology or Medicine Committee: E. Glynn Harmon, Supervisor Julie Hallmark Billie Grace Herring James D. Legler Brooke E. Sheldon Discovery and Information Use Patterns of Nobel Laureates in Physiology or Medicine by Karen Suzanne Balcom, B.A., M.L.S. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August, 2005 Dedication I dedicate this dissertation to my first teachers: my father, George Sheldon Balcom, who passed away before this task was begun, and to my mother, Marian Dyer Balcom, who passed away before it was completed. I also dedicate it to my dissertation committee members: Drs. Billie Grace Herring, Brooke Sheldon, Julie Hallmark and to my supervisor, Dr. Glynn Harmon. They were all teachers, mentors, and friends who lifted me up when I was down. Acknowledgements I would first like to thank my committee: Julie Hallmark, Billie Grace Herring, Jim Legler, M.D., Brooke E. Sheldon, and Glynn Harmon for their encouragement, patience and support during the nine years that this investigation was a work in progress. I could not have had a better committee. They are my enduring friends and I hope I prove worthy of the faith they have always showed in me. I am grateful to Dr. -

ILAE Historical Wall02.Indd 2 6/12/09 12:02:12 PM

1920–1929 1923 1927 1929 John Macloed Julius Wagner–Jauregg Sir Frederick Hopkins 1920920 1922922 1924924 1928928 August Krogh Otto Meyerhof Willem Einthoven Charles Nicolle 1922922 1923923 1926926 192992929 Archibald V Hill Frederick Banting Johannes Fibiger Christiann Eijkman 1920 The positive eff ect of the ketogenic diet on epilepsy is documented critically 1921 First case of progressive myoclonic epilepsy described 1922 Resection of adrenal gland used as treatment for epilepsy 1923 Dandy carries out the fi rst hemispherectomy in a human patient 1924 Hans Berger records the fi rst human EEG (reported in 1929) 1925 Pavlov fi nds a toxin from the brain of a dog with epilepsy which when injected into another dog will cure epilepsy – hope for human therapy 1926 Publication of L.J.J. Musken’s book Epilepsy: comparative pathogenesis, symptoms and treatment 1927 Cerebral angiography fi rst attempted by Egaz Moniz 1928 Wilder Penfi eld spends time in Foerster’s clinic and learns epilepsy surgical techniques. 1928 An abortive attempt to restart the ILAE fails 1929 Penfi eld’s fi rst ‘temporal lobectomy’ (a cortical resection) 1920 Cause of trypanosomiasis discovered 1925 Vitamin B discovered by Joseph Goldberger 1921 Psychodiagnostics and the Rorschach test invented 1926 First enzyme (urease) crystallised by James Sumner 1922 Insulin isolated by Frecerick G. Banting and Charles H. Best treats a diabetic patient 1927 Iron lung developed by Philip Drinker and Louis Shaw for the fi rst time 1928 Penicillin discovered by Alexander Fleming 1922 State Institute for Racial Biology formed in Uppsala 1929 Chemical basis of nerve impulse transmission discovered 1923 BCG vaccine developed by Albert Calmette and Jean–Marie Camille Guérin by Henry Dale and Harold W. -

Human Genetic Basis of Interindividual Variability in the Course of Infection

Human genetic basis of interindividual variability in the course of infection Jean-Laurent Casanovaa,b,c,d,e,1 aSt. Giles Laboratory of Human Genetics of Infectious Diseases, Rockefeller Branch, The Rockefeller University, New York, NY 10065; bHoward Hughes Medical Institute, New York, NY 10065; cLaboratory of Human Genetics of Infectious Diseases, Necker Branch, Inserm U1163, Necker Hospital for Sick Children, 75015 Paris, France; dImagine Institute, Paris Descartes University, 75015 Paris, France; and ePediatric Hematology and Immunology Unit, Assistance Publique–Hôpitaux de Paris, Necker Hospital for Sick Children, 75015 Paris, France This contribution is part of the special series of Inaugural Articles by members of the National Academy of Sciences elected in 2015. Contributed by Jean-Laurent Casanova, November 2, 2015 (sent for review September 15, 2015; reviewed by Max D. Cooper and Richard A. Gatti) The key problem in human infectious diseases was posed at the immunity (cell-autonomous mechanisms), then of cell-extrinsic turn of the 20th century: their pathogenesis. For almost any given innate immunity (phagocytosis of pathogens by professional cells), virus, bacterium, fungus, or parasite, life-threatening clinical disease and, finally, of cell-extrinsic adaptive immunity (somatic di- develops in only a small minority of infected individuals. Solving this versification of antigen-specific cells). Understanding the patho- infection enigma is important clinically, for diagnosis, prognosis, genesis of infectious diseases, particularly -

List of Nobel Laureates 1

List of Nobel laureates 1 List of Nobel laureates The Nobel Prizes (Swedish: Nobelpriset, Norwegian: Nobelprisen) are awarded annually by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, the Swedish Academy, the Karolinska Institute, and the Norwegian Nobel Committee to individuals and organizations who make outstanding contributions in the fields of chemistry, physics, literature, peace, and physiology or medicine.[1] They were established by the 1895 will of Alfred Nobel, which dictates that the awards should be administered by the Nobel Foundation. Another prize, the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences, was established in 1968 by the Sveriges Riksbank, the central bank of Sweden, for contributors to the field of economics.[2] Each prize is awarded by a separate committee; the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences awards the Prizes in Physics, Chemistry, and Economics, the Karolinska Institute awards the Prize in Physiology or Medicine, and the Norwegian Nobel Committee awards the Prize in Peace.[3] Each recipient receives a medal, a diploma and a monetary award that has varied throughout the years.[2] In 1901, the recipients of the first Nobel Prizes were given 150,782 SEK, which is equal to 7,731,004 SEK in December 2007. In 2008, the winners were awarded a prize amount of 10,000,000 SEK.[4] The awards are presented in Stockholm in an annual ceremony on December 10, the anniversary of Nobel's death.[5] As of 2011, 826 individuals and 20 organizations have been awarded a Nobel Prize, including 69 winners of the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences.[6] Four Nobel laureates were not permitted by their governments to accept the Nobel Prize. -

Human Genetic Basis of Interindividual Variability in the Course of Infection

Human genetic basis of interindividual variability in the INAUGURAL ARTICLE course of infection Jean-Laurent Casanovaa,b,c,d,e,1 aSt. Giles Laboratory of Human Genetics of Infectious Diseases, Rockefeller Branch, The Rockefeller University, New York, NY 10065; bHoward Hughes Medical Institute, New York, NY 10065; cLaboratory of Human Genetics of Infectious Diseases, Necker Branch, Inserm U1163, Necker Hospital for Sick Children, 75015 Paris, France; dImagine Institute, Paris Descartes University, 75015 Paris, France; and ePediatric Hematology and Immunology Unit, Assistance Publique–Hôpitaux de Paris, Necker Hospital for Sick Children, 75015 Paris, France This contribution is part of the special series of Inaugural Articles by members of the National Academy of Sciences elected in 2015. Contributed by Jean-Laurent Casanova, November 2, 2015 (sent for review September 15, 2015; reviewed by Max D. Cooper and Richard A. Gatti) The key problem in human infectious diseases was posed at the immunity (cell-autonomous mechanisms), then of cell-extrinsic turn of the 20th century: their pathogenesis. For almost any given innate immunity (phagocytosis of pathogens by professional cells), virus, bacterium, fungus, or parasite, life-threatening clinical disease and, finally, of cell-extrinsic adaptive immunity (somatic di- develops in only a small minority of infected individuals. Solving this versification of antigen-specific cells). Understanding the patho- infection enigma is important clinically, for diagnosis, prognosis, genesis of infectious -

Institut Pasteur

Series: Molecular Medicine Institutions INSTITUT PASTEUR Maxime Schwartz, Ph.D., Director General For more than a century, the Institut Pasteur has in Third World countries, and operates an 80-bed been at the forefront of the battle against infec- teaching hospital in Paris. tious disease. Based in Paris, it was first to isolate More than 1100 scientists work at the insti- the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) tute's research center in Paris (Fig. 1). virus in 1983. Over the years, it has been respon- sible for breakthrough discoveries that have en- abled medical science to control such virulent diseases as diphtheria, tetanus, tuberculosis, in- fluenza, yellow fever, and plague. Since 1908, eight Institut Pasteur scientists have been awarded the Nobel Prize for medicine and physiology. The Institut Pasteur was founded in 1887 by Louis Pasteur, the French scientist whose early experiments with fermentation led to pioneering research in bacteriology. A giant in science, Pas- teur discovered the principle of pasteurization. He developed techniques of vaccination to con- trol bacterial infection, as well as a successful vaccine against rabies. Louis Pasteur was committed both to basic FIG. 1. The Institut Pasteur, founded in 1987 research and its practical applications. His succes- in Paris, France sors have sustained this tradition, as reflected by the Institut Pasteur's unique history of accom- Since its founding, the Institut Pasteur has plishments. During Pasteur's lifetime, Emile brought together scientists from many different Roux and his colleagues discovered how to treat disciplines for postgraduate study. In 1994, 480 diphtheria with antitoxins; Elie Metchnikoff re- foreign visitors from 72 different countries par- ceived the Nobel Prize in 1908 for contributions ticipated in study programs at the institute. -

Nobel Prizes List from 1901

Nature and Science, 4(3), 2006, Ma, Nobel Prizes Nobel Prizes from 1901 Ma Hongbao East Lansing, Michigan, USA, Email: [email protected] The Nobel Prizes were set up by the final will of Alfred Nobel, a Swedish chemist, industrialist, and the inventor of dynamite on November 27, 1895 at the Swedish-Norwegian Club in Paris, which are awarding to people and organizations who have done outstanding research, invented groundbreaking techniques or equipment, or made outstanding contributions to society. The Nobel Prizes are generally awarded annually in the categories as following: 1. Chemistry, decided by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences 2. Economics, decided by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences 3. Literature, decided by the Swedish Academy 4. Peace, decided by the Norwegian Nobel Committee, appointed by the Norwegian Parliament, Stortinget 5. Physics, decided by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences 6. Physiology or Medicine, decided by Karolinska Institutet Nobel Prizes are widely regarded as the highest prize in the world today. As of November 2005, a total of 776 Nobel Prizes have been awarded, 758 to individuals and 18 to organizations. [Nature and Science. 2006;4(3):86- 94]. I. List of All Nobel Prize Winners (1901 – 2005): 31. Physics, Philipp Lenard 32. 1906 - Chemistry, Henri Moissan 1. 1901 - Chemistry, Jacobus H. van 't Hoff 33. Literature, Giosuè Carducci 2. Literature, Sully Prudhomme 34. Medicine, Camillo Golgi 3. Medicine, Emil von Behring 35. Medicine, Santiago Ramón y Cajal 4. Peace, Henry Dunant 36. Peace, Theodore Roosevelt 5. Peace, Frédéric Passy 37. Physics, J.J. Thomson 6. Physics, Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen 38. -

50 Nobel Laureates and Other Great Scientists Who Believe in God

50 NOBEL LAUREATES AND OTHER GREAT SCIENTISTS WHO BELIEVE IN GOD This book is an anthology of well-documented quotations. It is a free e-book. Copyright (c) 1995-2008 by Tihomir Dimitrov – compiler, M.Sc. in Psychology (1995), M.A. in Philosophy (1999). All rights reserved. This e-book and its contents may be used solely for non-commercial purposes. If used on the Internet, a link back to my site at http://nobelists.net would be appreciated. Compiler’s email: [email protected] CONTENTS Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………………………. 5 PART I. NOBEL SCIENTISTS (20th - 21st Century) …………...... 6 1. Albert EINSTEIN – Nobel Laureate in Physics ………………………………………………….. 6 2. Max PLANCK – Nobel Laureate in Physics ……………………………………………………... 8 3. Erwin SCHROEDINGER – Nobel Laureate in Physics ……………………………………...... 10 4. Werner HEISENBERG – Nobel Laureate in Physics ………………………………………….. 12 5. Robert MILLIKAN – Nobel Laureate in Physics ……………………………………………….. 14 6. Charles TOWNES – Nobel Laureate in Physics ……………………………………………….. 16 7. Arthur SCHAWLOW – Nobel Laureate in Physics …………………………………………….. 18 8. William PHILLIPS – Nobel Laureate in Physics ……………………………………………….. 19 9. William BRAGG – Nobel Laureate in Physics …………………………………………………. 20 10. Guglielmo MARCONI – Nobel Laureate in Physics …………………………………………. 21 11. Arthur COMPTON – Nobel Laureate in Physics ……………………………………………... 23 12. Arno PENZIAS – Nobel Laureate in Physics …………………………………………………. 25 13. Nevill MOTT – Nobel Laureate in Physics ……………………………………………………. 27 14. Isidor Isaac RABI – Nobel Laureate in Physics ……………………………………………… 28 15. Abdus SALAM – Nobel Laureate in Physics …………………………………………………. 28 16. Antony HEWISH – Nobel Laureate in Physics ……………………………………………….. 29 17. Joseph H. TAYLOR, Jr. – Nobel Laureate in Physics ………………………………………. 30 18. Alexis CARREL – Nobel Laureate in Medicine and Physiology ……………………………. 31 19. John ECCLES – Nobel Laureate in Medicine and Physiology ……………………………… 33 20. Joseph MURRAY – Nobel Laureate in Medicine and Physiology …………………………. -

Typhus” Entity

Table S1. Historical Chronology of Milestones - the Gradual Dissection of the “Typhus” Entity. Year Important findings Comments Ref. Hippocrates defines typhus - as “fever with a 460 BC confused state of the intellect - a tendency to [1] stupor”. Thucydides and Hippocrates first describe 430 BC [2] epidemic typhus cases. Description of regional First clinical accounts of Tsutsugamushi disease 313 BC vector mites, no linkage to [3] in the “Zhouhofang”, a Chinese clinical manual. transmission No distinction made 15th Epidemic typhus and endemic typhus between different forms of [4] century (Tabardillo) rages in Europe. typhus The five epidemics known as the ‘English Probably relapsing fever 1485−1551 [5, 6] Sweat’ occur in the United Kingdom. (Borrelia recurrentis) Girolamo Fracastoro–Fracastorius (1478−1553) 1546 differentiates typhus from plague in De [7-9] contagione et contagiosis morbis. Early Typhus = Typhoid and Typhus and ‘Relapsing Era of differential [10−13] 1700s Fever’ diagnostic confusion! John Huxham made the first distinction Typhus = ‘‘slow nervous’’ 1750 between epidemic typhus and typhoid fever in fever Typhoid = ‘‘putrid [10] the United Kingdom. malignant’’ fever Boisier de Sauvages in Montpellier creates the Based on clinical 1760 clinical term “Typhus exanthematique” for appearance of [14] epidemic typhus. characteristic skin rash James Lind (1716−1794) promotes hygienic Limes for prevention of 1762 measures during typhus outbreaks to reduce [8,9] scorbut. mortality. Hakuju Hashimoto first described a tsutsuga The basis of the name 1810 (disease, harm, noxious) resembling typhus, in [15] ‘Tsutsugamushi disease’ the Niigata prefecture, Japan. Napoleon suffers the greatest loss of troops in 1812−1813 eastern Europe to epidemic typhus (and Trench [16,17] Fever). -

Infectious Nobelitis

BOOK REVIEW Infectious Nobelitis given for modes of transmission—malaria by mosquitos (Ronald Ross, 1902), typhus by lice (Charles Nicolle, 1928) and the control of both vec- The Nobel Prize Winning tors by DDT (Paul Müller, 1948)—as for pathogen discovery, such as the Discoveries in Infectious Diseases malaria parasite (Charles Laveran, 1907) and Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Robert Koch, 1905). Henrique de Rocha Lima, who identified the typhus David Rifkind and Geraldine L. Freeman pathogen Rickettsia prowazekii, was not awarded a prize, while Ricketts and Prowazek themselves died of their disease, as did Jesse Lazear from Elsevier Academic Press, 2005 self-testing the mosquito transmission of yellow fever. Nobel Prizes are 166 pp, paperback, $29.95 not awarded posthumously, even to those who sacrificed their lives for the ISBN 0123693535 progress of science. From their very inception, the Nobel Prizes in infectious diseases Reviewed by Robin A Weiss have been contentious. Von Behring was cited for developing diph- theria and tetanus antitoxins, but Shibasaburo Kitasato played just as important a role, and both depended on Paul Ehrlich’s precise methods http://www.nature.com/naturemedicine of serum standardization. Did the Nobel committee insist on only one This short and readable book describes 25 Nobel Prize–winning discover- name, or did they not regard a Japanese colleague as a serious con- ies in infectious diseases. Following a brief introduction on Alfred Nobel tender? Italian parasitologists feel sore that Giovanni Battista Grassi and the prizes, the book is divided into five parts: immunity, antimicro- was not recognized alongside Ross because he demonstrated mosquito bials, bacteria, viruses (including prions) and parasites.