Infectious Nobelitis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE ERADICATION of POLIOMYELITIS (Fhe Albert V.• Sabin Lecture)

THE ERADICATIONOF POLIOMYELITIS (fhe Albert V.•Sabin Lecture) by Donald Henderson, M.D., M.P.H. University Distinguished Service Professor The JohnsHopkins University Baltimore, Maryland 21205 Cirode Quadros, M.D., M.P.H. Regional Advisor Expanded Programme on lmmunii.ation Pan American Health Organization 525 23rd Street, N. W. Washington, D.C. 20037 Introduction The understanding and ultimate conquest of poliomyelitis was Albert Sabin's life long preoccupation, beginning with his earliest work in 1931. (Sabin and Olitsky, 1936; Sabin, 1965) The magnitude of that effort was aptly summarized by Paul in his landmark history of polio: "No man has ever contributed so much effective information - and so continuously over so many years - to so many aspects of poliomyelitis." (Paul, 1971) Thus, appropriately, this inaugural Sabin lecture deals with poliomyelitis and its eradication. Polio Vaccine Development and Its Introduction In the quest for polio control and ultimately eradication, several landmarks deserve special mention. At the outset, progress was contingent on the development of a vaccine and the production of a vaccine, in turn, necessitated the discovery of new methods to grow large quantities of virus. The breakthrough occurred in 1969 when Enders and his colleagues showed that large quantities of poliovirus could be grown in a variety of human cell tissue cultures and that the virus could be quantitatively assayed by its cytopathic effect. (Enders, Weller and Robbins, 1969) Preparation of an inactivated vaccine was, in principle, a comparatively straightforward process. In brief, large quantities of virus were grown. then purified, inactivated with formalin and bottled. Assurance that the virus had been inactivated could be demonstrated by growth in tissue. -

Alexander Fleming

PMI Ciência: Mitos, Histórias e Factos A. Fleming Referência: http://www.time.com/time/time100/scientist/profile/fleming.html Alexander Fleming A spore that drifted into his lab and took root on a culture dish started a chain of events that altered forever the treatment of bacterial infections By DR. DAVID HO The improbable chain of events that led Alexander bacteriologist." Although he went on to perform Fleming to discover penicillin in 1928 is the stuff of additional experiments, he never conducted the one which scientific myths are made. Fleming, a young that would have been key: injecting penicillin into Scottish research scientist with a profitable side infected mice. Fleming's initial work was reported in practice treating the syphilis infections of prominent 1929 in the British Journal of Experimental Pathology, London artists, was pursuing his pet theory — that his but it would remain in relative obscurity for a decade. own nasal mucus had antibacterial effects — when he By 1932, Fleming had abandoned his work on left a culture plate smeared with Staphylococcus penicillin. He would have no further role in the bacteria on his lab bench while he went on a two-week subsequent development of this or any other antibiotic, holiday. aside from happily providing other researchers with When he returned, he noticed a clear halo surrounding samples of his mold. It is said that he lacked both the the yellow-green growth of a mold that had chemical expertise to purify penicillin and the accidentally contaminated the plate. Unknown to him, conviction that drugs could cure serious infections. -

Hidden Cargo: a Cautionary Tale About Agroterrorism and the Safety of Imported Produce

HIDDEN CARGO: A CAUTIONARY TALE ABOUT AGROTERRORISM AND THE SAFETY OF IMPORTED PRODUCE 1. INTRODUCTION The attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon on Septem ber 11, 2001 ("9/11") demonstrated to the United States ("U.S.") Gov ernment the U.S. is vulnerable to a wide range of potential terrorist at tacks. l The anthrax attacks that occurred immediately following the 9/11 attacks further demonstrated the vulnerability of the U.S. to biological attacks. 2 The U.S. Government was forced to accept its citizens were vulnerable to attacks within its own borders and the concern of almost every branch of government turned its focus toward reducing this vulner ability.3 Of the potential attacks that could occur, we should be the most concerned with biological attacks on our food supply. These attacks are relatively easy to initiate and can cause serious political and economic devastation within the victim nation. 4 Generally, acts of deliberate contamination of food with biological agents in a terrorist act are defined as "bioterrorism."5 The World Health Organization ("WHO") uses the term "food terrorism" which it defines as "an act or threat of deliberate contamination of food for human con- I Rona Hirschberg, John La Montagne & Anthony Fauci, Biomedical Research - An Integral Component of National Security, NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE (May 20,2004), at 2119, available at http://contenLnejrn.org/cgi/reprint/350/2112ll9.pdf (dis cussing the vulnerability of the U.S. to biological, chemical, nuclear, and radiological terrorist attacks). 2 Id.; Anthony Fauci, Biodefence on the Research Agenda, NATURE, Feb. -

Fleming Vs. Florey: It All Comes Down to the Mold Kristin Hess La Salle University

The Histories Volume 2 | Issue 1 Article 3 Fleming vs. Florey: It All Comes Down to the Mold Kristin Hess La Salle University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/the_histories Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Hess, Kristin () "Fleming vs. Florey: It All Comes Down to the Mold," The Histories: Vol. 2 : Iss. 1 , Article 3. Available at: https://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/the_histories/vol2/iss1/3 This Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Scholarship at La Salle University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in The iH stories by an authorized editor of La Salle University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Histories, Vol 2, No. 1 Page 3 Fleming vs. Florey: It All Comes Down to the Mold Kristen Hess Without penicillin, the world as it is known today would not exist. Simple infections, earaches, menial operations, and diseases, like syphilis and pneumonia, would possibly all end fatally, shortening the life expectancy of the population, affecting everything from family-size and marriage to retirement plans and insurance policies. So how did this “wonder drug” come into existence and who is behind the development of penicillin? The majority of the population has heard the “Eureka!” story of Alexander Fleming and his famous petri dish with the unusual mold growth, Penicillium notatum. Very few realize that there are not only different variations of the Fleming discovery but that there are also other people who were vitally important to the development of penicillin as an effective drug. -

Die Woche Spezial

In cooperation with DIE WOCHE SPEZIAL >> Autographs>vs.>#NobelSelfie Special >> Big>Data>–>not>a>big>deal,> Edition just>another>tool >> Why>Don’t>Grasshoppers> Catch>Colds? SCIENCE SUMMIT The>64th>Lindau>Nobel>Laureate>Meeting> devoted>to>Physiology>and>Medicine More than 600 young scientists came to Lindau to meet 37 Nobel laureates CAREER WONGSANIT > Women>to>Women: SUPHAKIT > / > Science>and>Family FOTOLIA INFLAMMATION The>Stress>of>Ageing > FLASHPICS > / > MEETINGS > FOTOLIA LAUREATE > CANCER RESEARCH NOBEL > LINDAU > / > J.>Michael>Bishop>and GÄRTNER > FLEMMING > JUAN > / the>Discovery>of>the>first> > CHRISTIAN FOTOLIA Human>Oncogene EDITORIAL IMPRESSUM Chefredakteur: Prof. Dr. Carsten Könneker (v.i.S.d.P.) Dear readers, Redaktionsleiter: Dr. Daniel Lingenhöhl Redaktion: Antje Findeklee, Jan Dönges, Dr. Jan Osterkamp where>else>can>aspiring>young>scientists> Ständige Mitarbeiter: Lars Fischer Art Director Digital: Marc Grove meet>the>best>researchers>of>the>world> Layout: Oliver Gabriel Schlussredaktion: Christina Meyberg (Ltg.), casually,>and>discuss>their>research,>or>their> Sigrid Spies, Katharina Werle Bildredaktion: Alice Krüßmann (Ltg.), Anke Lingg, Gabriela Rabe work>–>or>pressing>global>problems?>Or> Verlag: Spektrum der Wissenschaft Verlagsgesellschaft mbH, Slevogtstraße 3–5, 69126 Heidelberg, Tel. 06221 9126-600, simply>discuss>soccer?>Probably>the>best> Fax 06221 9126-751; Amtsgericht Mannheim, HRB 338114, UStd-Id-Nr. DE147514638 occasion>is>the>annual>Lindau>Nobel>Laure- Geschäftsleitung: Markus Bossle, Thomas Bleck Marketing und Vertrieb: Annette Baumbusch (Ltg.) Leser- und Bestellservice: Helga Emmerich, Sabine Häusser, ate>Meeting>in>the>lovely>Bavarian>town>of> Ute Park, Tel. 06221 9126-743, E-Mail: [email protected] Lindau>on>Lake>Constance. Die Spektrum der Wissenschaft Verlagsgesellschaft mbH ist Kooperati- onspartner des Nationalen Instituts für Wissenschaftskommunikation Daniel>Lingenhöhl> GmbH (NaWik). -

Curing Childhood Leukemia, October 1997

This article was published in 1997 and has not been updated or revised. CURING CHILDHOOD LEUKEMIA ancer is an insidious disease. The culprit is not bacterial infections, viral infections, and many other a foreign invader, but the altered descendants illnesses. _) of our own cells, which reproduce uncontrol The fight against cancer has been more of a war of lably. In this civil war, it is hard to distinguish friend attrition than a series of spectacular, instantaneous vic from foe, to tat;get the cancer cells without killing the tories, and the research into childhood leukemia over the healthy cells. Most of our current cancer therapies, last 40 years is no exception. But most of the children who including the cure for childhood leukemia described here, are victims of this disease can now be cured, and the are based on the fact that cancer cells reproduce without drugs that made this possible are the antimetabolite some of the safeguards present in normal cells. If we can drugs that will be described here. The logic behind those interfere with cell reproduction, the cancer cells will be drugs came from a wide array of research that defined hit disproportionately hard and often will not recover. the chemical workings of the cell--research done by scien The scientists and physicians who devised the cure for tists who could not know that their findings would even childhood leukemia pioneered a rational approach to tually save the lives of up to thirty thousand children in destroying cancer cells, using knowledge about the cell the United States. -

A Guide to Preparing Multiple Choice Items

A Guide to Preparing Multiple Choice Items Introduction The most commonly used type of test item in admissions, certification, and licensure examinations is the multiple choice item. The purpose of this guide is to assist test developers and representatives of professional associations in becoming more skilled in writing multiple choice test items. Preparing multiple choice items may appear on the surface to be a relatively simple task, given familiarity with the subject matter. However, experienced test authors find that this task actually requires a great deal of skill, patience, and creativity. In the sections that follow, general knowledge is used as the content of the examples, in order to facilitate understanding of the principles by professionals from diverse content areas. The skills needed for writing quality items are similar regardless of content discipline. Like any other skill, multiple choice item writing requires a significant amount of painstaking practice with appropriate feedback. It is essential that you try out your multiple choice items on others. This process will help you to uncover ambiguities in wording and unintended violations of item writing principles. Feedback from others will greatly enhance your item writing quality and productivity. Parts of the Multiple Choice Item All multiple choice items consist of two basic parts: the stem and the responses. The stem is the introductory statement or question that elicits the correct answer. The responses are suggested answers which complete the statement or answer the question asked in the stem, only one of which is the correct answer. In the examples that follow, four responses (i.e., 1 correct response and 3 incorrect responses) are presented. -

Jonas Salk at the National Press Club, April 12, 1965

Jonas Salk at the National Press Club, April 12, 1965 Jonas Salk, May 1962. A.F.P. – D.P.A. Photos. National Press Club Archives On the tenth anniversary of the licensing of the polio vaccine he developed, Dr. Jonas E. Salk (1914-1995) visited Washington to accept a joint congressional resolution that hailed the vaccine as “one of the most significant medical achievements of our time.” At the White House, President Johnson offered Salk his congratulations. The day also marked the twentieth anniversary of the death of former President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who, having suffered from paralytic polio since 1921, had established the foundation that funded Salk’s efforts. Following his meetings with Congress and the President, Salk gave a talk and answered reporters’ questions at a National Press Club luncheon. In the title of its lead editorial ten years earlier celebrating the successful testing of the new vaccine, the New York Times proclaimed the “Dawn of a New Medical Day.” Testing of the vaccine, like the funding for its development, had engaged the participation of millions of ordinary American citizens. Through March of Dimes campaigns, hundreds of thousands of volunteers went door-to-door raising $41 million in 1952 alone from average donations of 27 cents. The tests involved 1.8 million school children, 200,000 volunteers, 64,000 teachers, and 60,000 physicians, nurses, and health officials, making it the largest clinical trial in history. Interpreting the jubilant 1 reaction to news that the vaccine had been proven safe and effective, the Times commented, “Gone are the old helplessness, the fear of an invisible enemy, the frustration of physicians.” Poliomyelitis, also known as infantile paralysis, is an extremely contagious viral infection caused by any of three types of poliovirus. -

Poliomyelitis in the Lone Star State

POLIOMYELITIS IN THE LONE STAR STATE: A BRIEF EXAMINATION IN RURAL AND URBAN COMMUNITIES THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree Master of Arts By Jason C. Lee San Marcos, Texas December, 2005 Insert signature page here ii COPYRIGHT By Jason Chu Lee 2005 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS It leaves me in a stupor to contemplate all those I have to thank for aiding me in this effort. If I leave anybody out, please accept my most humble apologies, as the list is long. I will be the first to admit that this work is flawed, despite the best efforts of my committee to save me from myself. Had I utilized them more, this piece would only be improved. I had never undertaken a project of this scope before and though I believe I have accomplished much, the experience has been humbling. Never again will I utter the phrase, “just a thesis.” My biggest thanks go out to Dr. Mary Brennan, my committee chair and mentor. Without her guidance I most certainly would have needed to take comprehensive finals to graduate. She helped me salvage weeks of research that I thought had no discernable use. But Dr. Brennan, despite her very, very busy schedule with the department and her family, still found the time to help me find my thesis in all the data. She is well loved in the department for obvious reasons, as she has a gift for being firm and professional while remaining compassionate. Dr. James Wilson and Dr. -

Mosquitoes, Quinine and the Socialism of Italian Women 1900–1914

MOSQUITOES, QUININE AND THE SOCIALISM OF ITALIAN WOMEN 1900–1914 Malaria qualifies as a major issue of modern Italian history because of the burden of death, suffering and economic cost that it imposed. But it is fruitful to examine its history from a more hopeful, if largely neglected, vantage point. Paradoxically, mal- aria — or rather the great campaign to eradicate it with quinine — played a substantial political role. It promoted the rise of the Italian labour movement, the formation of a socialist aware- ness among farmworkers and the establishment of a collective consciousness among women. In 1900 the Italian parliament declared war on malaria. After a series of vicissitudes, this project achieved final victory in 1962 when the last indigenous cases were reported.1 Italy thus provided the classic example of the purposeful eradication of malaria. The argument here is that the early phase of this campaign down to the First World War played a profoundly subversive role. The campaign served as a catalyst to mass movements by farmworkers, especially women. Three geographical areas were most affected: the rice belt of Novara and Pavia provinces in the North, the Roman Campagna in the Centre, and the province of Foggia in the South. Inevitably, this argument involves the intersection of malaria with two further disasters that befell millions. One was the mis- fortune of being born a farm labourer in a society where serious commentators debated who suffered more — Italian braccianti (farmworkers) in the latter half of the nineteenth century or American slaves in the first.2 The other disaster was the burden of being not only a field hand but also a woman in a nation that Anna Kuliscioff, the most prominent feminist of the period, 1 World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe, Prevention of the Reintroduction of Malaria in the Countries of the Western Mediterranean: Report on a WHO Meeting, Erice (Italy), 23–27 October 1979 (Geneva, 1979), 5. -

Naturvidenskabernes Kanonisering. Forskere, Erkendelser Eller Kulturarv

NORDISK MUSEOLOGI 2006 G 2, S. 27-44 Naturvidenskabernes kanonisering. Forskere, erkendelser eller kulturarv KRISTIAN HVIDTFELT NIELSEN* Title: The ”canonisation” of the natural sciences. Abstract: This paper concerns recent official attempts to place science in Denmark within the context of a cultural canon. Based on differentiation between Mode 1 and 2 knowledge production, the paper points out that such attempts are highly contextualised and contingent on their different modes of application. Consequent- ly, they entangle scientific expertise with other social skills and qualifications. Like science museums and science centres, they are a means of dealing with science in the public agora, i.e. the public sphere in which negotiations, mediations, consulta- tions and contestations regarding science increasingly take place. Analysing the am- biguities and uncertainties associated with the recent official placing of science wit- hin an overall cultural canon for Denmark, this paper concludes that even though the agora embodies antagonistic forms of interaction, it might also lead the way to producing socially robust knowledge about science. Keywords: Cultural canon, science, Mode 1 and 2 knowledge production, Mode 2 society, agora, science museums, science centres. Naturvidenskab er ikke med i den officielle, denskabskanoner samt deres bredere betyd- danske kulturkanon, som blev sat i værk af ning for offentlighedens forståelse af naturvi- Kulturministeriet i 2005 (Kulturministeriet denskab, som jeg i denne artikel vil komme 2006). Det -

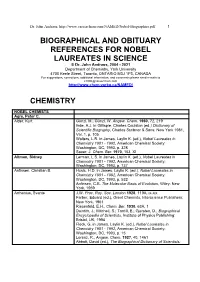

Biographical References for Nobel Laureates

Dr. John Andraos, http://www.careerchem.com/NAMED/Nobel-Biographies.pdf 1 BIOGRAPHICAL AND OBITUARY REFERENCES FOR NOBEL LAUREATES IN SCIENCE © Dr. John Andraos, 2004 - 2021 Department of Chemistry, York University 4700 Keele Street, Toronto, ONTARIO M3J 1P3, CANADA For suggestions, corrections, additional information, and comments please send e-mails to [email protected] http://www.chem.yorku.ca/NAMED/ CHEMISTRY NOBEL CHEMISTS Agre, Peter C. Alder, Kurt Günzl, M.; Günzl, W. Angew. Chem. 1960, 72, 219 Ihde, A.J. in Gillispie, Charles Coulston (ed.) Dictionary of Scientific Biography, Charles Scribner & Sons: New York 1981, Vol. 1, p. 105 Walters, L.R. in James, Laylin K. (ed.), Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 1901 - 1992, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1993, p. 328 Sauer, J. Chem. Ber. 1970, 103, XI Altman, Sidney Lerman, L.S. in James, Laylin K. (ed.), Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 1901 - 1992, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1993, p. 737 Anfinsen, Christian B. Husic, H.D. in James, Laylin K. (ed.), Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 1901 - 1992, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1993, p. 532 Anfinsen, C.B. The Molecular Basis of Evolution, Wiley: New York, 1959 Arrhenius, Svante J.W. Proc. Roy. Soc. London 1928, 119A, ix-xix Farber, Eduard (ed.), Great Chemists, Interscience Publishers: New York, 1961 Riesenfeld, E.H., Chem. Ber. 1930, 63A, 1 Daintith, J.; Mitchell, S.; Tootill, E.; Gjersten, D., Biographical Encyclopedia of Scientists, Institute of Physics Publishing: Bristol, UK, 1994 Fleck, G. in James, Laylin K. (ed.), Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 1901 - 1992, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1993, p. 15 Lorenz, R., Angew.