Human Genetic Basis of Interindividual Variability in the Course of Infection

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

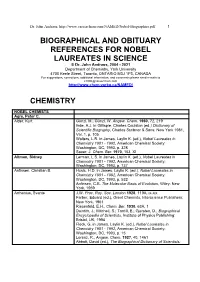

Biographical References for Nobel Laureates

Dr. John Andraos, http://www.careerchem.com/NAMED/Nobel-Biographies.pdf 1 BIOGRAPHICAL AND OBITUARY REFERENCES FOR NOBEL LAUREATES IN SCIENCE © Dr. John Andraos, 2004 - 2021 Department of Chemistry, York University 4700 Keele Street, Toronto, ONTARIO M3J 1P3, CANADA For suggestions, corrections, additional information, and comments please send e-mails to [email protected] http://www.chem.yorku.ca/NAMED/ CHEMISTRY NOBEL CHEMISTS Agre, Peter C. Alder, Kurt Günzl, M.; Günzl, W. Angew. Chem. 1960, 72, 219 Ihde, A.J. in Gillispie, Charles Coulston (ed.) Dictionary of Scientific Biography, Charles Scribner & Sons: New York 1981, Vol. 1, p. 105 Walters, L.R. in James, Laylin K. (ed.), Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 1901 - 1992, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1993, p. 328 Sauer, J. Chem. Ber. 1970, 103, XI Altman, Sidney Lerman, L.S. in James, Laylin K. (ed.), Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 1901 - 1992, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1993, p. 737 Anfinsen, Christian B. Husic, H.D. in James, Laylin K. (ed.), Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 1901 - 1992, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1993, p. 532 Anfinsen, C.B. The Molecular Basis of Evolution, Wiley: New York, 1959 Arrhenius, Svante J.W. Proc. Roy. Soc. London 1928, 119A, ix-xix Farber, Eduard (ed.), Great Chemists, Interscience Publishers: New York, 1961 Riesenfeld, E.H., Chem. Ber. 1930, 63A, 1 Daintith, J.; Mitchell, S.; Tootill, E.; Gjersten, D., Biographical Encyclopedia of Scientists, Institute of Physics Publishing: Bristol, UK, 1994 Fleck, G. in James, Laylin K. (ed.), Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 1901 - 1992, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1993, p. 15 Lorenz, R., Angew. -

Introduction to Microbiology: Then and Now

© Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC (right) Courtesy of Jed Alan Fuhrman, University of Southern University (right) Courtesy of Jed Alan Fuhrman, (left) Courtesy of JPL-Caltech/NASA. California. CHAPTER 1 NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION Introduction© Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC to © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC Microbiology:NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION ThenNOT FOR and SALE OR DISTRIBUTIONNow © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALECHAPTER OR DISTRIBUTION KEY CONCEPTS NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION 1-1 Microbial Communities Support and Affect All Life on Earth 1-2 The Human Body Has Its Own Microbiome 1-3 Microbiology Then: The Pioneers 1-4 The Microbial© WorldJones Is Cat& Bartlettaloged into Learning, Unique Groups LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC 1-5 MicrobiologyNOT Now :FOR Challenges SALE Remain OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC Earth’s Microbiomes NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION Space and the universe often appear to be an unlimited frontier. The chapter opener image on the left shows one of an estimated 350 billion large galaxies and more than 1024 stars in the known universe. However, there is another 30 invisible frontier here on Earth. This is the microbial universe, which consists of more than 10 microorganisms (or microbes for short). As the chapter opener image on the right shows, microbes might be microscopic in size, but, as we will see, they are magnificent in their evolutionary diversity and astounding in their sheer numbers. -

Nobel Prizes in Physiology Or Medicine with an Emphasis on Bacteriology

J Med Bacteriol. Vol. 8, No. 3, 4 (2019): pp.49-57 jmb.tums.ac.ir Journal of Medical Bacteriology Nobel Prizes in Physiology or Medicine with an Emphasis on Bacteriology 1 1 2 Hamid Hakimi , Ebrahim Rezazadeh Zarandi , Siavash Assar , Omid Rezahosseini 3, Sepideh Assar 4, Roya Sadr-Mohammadi 5, Sahar Assar 6, Shokrollah Assar 7* 1 Department of Microbiology, Medical School, Rafsanjan University of Medical Sciences, Rafsanjan, Iran. 2 Department of Anesthesiology, Medical School, Kerman University of Medical Sciences, Kerman, Iran. 3 Department of Infectious and Tropical Diseases, Imam Khomeini Hospital Complex, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. 4 Department of Pathology, Dental School, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran. 5 Dental School, Rafsanjan University of Medical Sciences, Rafsanjan, Iran. 6 Dental School, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran. 7 Department of Microbiology and Immunology of Infectious Diseases Research Center, Research Institute of Basic Medical Sciences, Rafsanjan University of Medical Sciences, Rafsanjan, Iran. ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article type: Background: Knowledge is an ocean without bound or shore, the seeker of knowledge is (like) the Review Article diver in those seas. Even if his life is a thousand years, he will never stop searching. This is the result Article history: of reflection in the book of development. Human beings are free and, to some extent, have the right to Received: 02 Feb 2019 choose, on the other hand, they are spiritually oriented and innovative, and for this reason, the new Revised: 28 Mar 2019 discovery and creativity are felt. This characteristic, which is in the nature of human beings, can be a Accepted: 06 May 2019 motive for the revision of life and its tools and products. -

Balcomk41251.Pdf (558.9Kb)

Copyright by Karen Suzanne Balcom 2005 The Dissertation Committee for Karen Suzanne Balcom Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Discovery and Information Use Patterns of Nobel Laureates in Physiology or Medicine Committee: E. Glynn Harmon, Supervisor Julie Hallmark Billie Grace Herring James D. Legler Brooke E. Sheldon Discovery and Information Use Patterns of Nobel Laureates in Physiology or Medicine by Karen Suzanne Balcom, B.A., M.L.S. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August, 2005 Dedication I dedicate this dissertation to my first teachers: my father, George Sheldon Balcom, who passed away before this task was begun, and to my mother, Marian Dyer Balcom, who passed away before it was completed. I also dedicate it to my dissertation committee members: Drs. Billie Grace Herring, Brooke Sheldon, Julie Hallmark and to my supervisor, Dr. Glynn Harmon. They were all teachers, mentors, and friends who lifted me up when I was down. Acknowledgements I would first like to thank my committee: Julie Hallmark, Billie Grace Herring, Jim Legler, M.D., Brooke E. Sheldon, and Glynn Harmon for their encouragement, patience and support during the nine years that this investigation was a work in progress. I could not have had a better committee. They are my enduring friends and I hope I prove worthy of the faith they have always showed in me. I am grateful to Dr. -

Introduction to Plant Diseases

An Introduction to Plant Diseases David L. Clement, Regional Specialist - Plant Pathology Maryland Institute For Agriculture And Natural Resources Modified by Diane M. Karasevicz, Cornell Cooperative Extension Cornell University, Department of Plant Pathology Learning Objectives 1. Gain a general understanding of disease concepts. 2. Become familiar with the major pathogens that cause disease in plants. 3. Gain an understanding of how pathogens cause disease and their interactions with plants.· 4. Be able to distinguish disease symptoms from other plant injuries. 5. Understand the basic control strategies for plant diseases. Introduction to Plant Diseases The study of plant disease is covered under the science of Phytopathology, which is more commonly called Plant Pathology. Plant pathologists study plant diseases caused by fungi, bacteria. viruses and similar very small microbes (mlos. viroids, etc.), parasitic plants and nematodes. They also study plant disorders caused by abiotic problems. or non-living causes, associated with growing conditions. These include drought and freezing damage. nutrient imbalances, and air pollution damage. A Brief History of Plant Disea~es Plant diseases have had profound effects on mankind through the centuries as evidenced by Biblical references to blasting and mildew of plants. The Greek philosopher Theophrastus (370-286 BC) was the first to describe maladies of trees,. cereals and legumes that we today classify as leaf scorch, rots, scab, and cereal rust. The Romans were also aware of rust diseases of their grain crops. They celebrated lhe holiday of Robigalia that involved sacrifices of reddish colored dogs and catde in an attempt to appease the rust god Robigo. With the invention of the microscope in th~ seventeenth century fungi and bacteria associated with plants were investigated. -

History of Microbiology: Spontaneous Generation Theory

HISTORY OF MICROBIOLOGY: SPONTANEOUS GENERATION THEORY Microbiology often has been defined as the study of organisms and agents too small to be seen clearly by the unaided eye—that is, the study of microorganisms. Because objects less than about one millimeter in diameter cannot be seen clearly and must be examined with a microscope, microbiology is concerned primarily with organisms and agents this small and smaller. Microbial World Microorganisms are everywhere. Almost every natural surface is colonized by microbes (including our skin). Some microorganisms can live quite happily in boiling hot springs, whereas others form complex microbial communities in frozen sea ice. Most microorganisms are harmless to humans. You swallow millions of microbes every day with no ill effects. In fact, we are dependent on microbes to help us digest our food and to protect our bodies from pathogens. Microbes also keep the biosphere running by carrying out essential functions such as decomposition of dead animals and plants. Microbes are the dominant form of life on planet Earth. More than half the biomass on Earth consists of microorganisms, whereas animals constitute only 15% of the mass of living organisms on Earth. This Microbiology course deals with • How and where they live • Their structure • How they derive food and energy • Functions of soil micro flora • Role in nutrient transformation • Relation with plant • Importance in Industries The microorganisms can be divided into two distinct groups based on the nucleus structure: Prokaryotes – The organism lacking true nucleus (membrane enclosed chromosome and nucleolus) and other organelles like mitochondria, golgi body, entoplasmic reticulum etc. are referred as Prokaryotes. -

Louis Pasteur

Britannica LaunchPacks | Louis Pasteur Louis Pasteur For Grades 6-8 This Pack contains: 5 ARTICLES 4 IMAGES 1 VIDEO © 2020 Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. 1 of 47 Britannica LaunchPacks | Louis Pasteur Louis Pasteur (1822–95). The French chemist Louis Pasteur devoted his life to solving practical problems of industry, agriculture, and medicine. His discoveries have saved countless lives and created new wealth for the world. Among his discoveries are the pasteurization process and ways of preventing silkworm diseases, anthrax, chicken cholera, and rabies. Louis Pasteur. Archives Photographiques, Paris Pasteur sought no profits from his discoveries, and he supported his family on his professor’s salary or on a modest government allowance. In the laboratory he was a calm and exact worker; but once sure of his findings, he vigorously defended them. Pasteur was an ardent patriot, zealous in his ambition to make France great through science. Scholar and Scientist Louis Pasteur was born on Dec. 27, 1822, in Dôle, France. His father was a tanner. In 1827 the family moved to nearby Arbois, where Louis went to school. He was a hard-working pupil but not an especially brilliant one. When he was 17 he received a degree of bachelor of letters at the Collège Royal de Besançon. For the next three years he tutored younger students and prepared for the École Normale Supérieure, a noted teacher-training college in Paris. As part of his studies he investigated the crystallographic, chemical, and optical properties of © 2020 Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. 2 of 47 Britannica LaunchPacks | Louis Pasteur various forms of tartaric acid. -

ILAE Historical Wall02.Indd 2 6/12/09 12:02:12 PM

1920–1929 1923 1927 1929 John Macloed Julius Wagner–Jauregg Sir Frederick Hopkins 1920920 1922922 1924924 1928928 August Krogh Otto Meyerhof Willem Einthoven Charles Nicolle 1922922 1923923 1926926 192992929 Archibald V Hill Frederick Banting Johannes Fibiger Christiann Eijkman 1920 The positive eff ect of the ketogenic diet on epilepsy is documented critically 1921 First case of progressive myoclonic epilepsy described 1922 Resection of adrenal gland used as treatment for epilepsy 1923 Dandy carries out the fi rst hemispherectomy in a human patient 1924 Hans Berger records the fi rst human EEG (reported in 1929) 1925 Pavlov fi nds a toxin from the brain of a dog with epilepsy which when injected into another dog will cure epilepsy – hope for human therapy 1926 Publication of L.J.J. Musken’s book Epilepsy: comparative pathogenesis, symptoms and treatment 1927 Cerebral angiography fi rst attempted by Egaz Moniz 1928 Wilder Penfi eld spends time in Foerster’s clinic and learns epilepsy surgical techniques. 1928 An abortive attempt to restart the ILAE fails 1929 Penfi eld’s fi rst ‘temporal lobectomy’ (a cortical resection) 1920 Cause of trypanosomiasis discovered 1925 Vitamin B discovered by Joseph Goldberger 1921 Psychodiagnostics and the Rorschach test invented 1926 First enzyme (urease) crystallised by James Sumner 1922 Insulin isolated by Frecerick G. Banting and Charles H. Best treats a diabetic patient 1927 Iron lung developed by Philip Drinker and Louis Shaw for the fi rst time 1928 Penicillin discovered by Alexander Fleming 1922 State Institute for Racial Biology formed in Uppsala 1929 Chemical basis of nerve impulse transmission discovered 1923 BCG vaccine developed by Albert Calmette and Jean–Marie Camille Guérin by Henry Dale and Harold W. -

Science -- Lederberg 288 (5464): 287

Science -- Lederberg 288 (5464): 287 Institution: COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY | Sign In as Individual | FAQ | Access Rights | Join AAAS Summary of this Article Infectious History dEbates: Submit a response to this article Joshua Lederberg* Related commentary and In 1530, to express his ideas on the origin of syphilis, the Italian articles in Science physician Girolamo Fracastoro penned Syphilis, sive morbus products Gallicus (Syphilis, or the French disease) in verse. In it he taught that this sexually transmitted disease was spread by "seeds" Download to Citation distributed by intimate contact. In later writings, he expanded this Manager early "contagionist" theory. Besides contagion by personal contact, he described contagion by indirect contact, such as the handling or Alert me when: wearing of clothes, and even contagion at a distance, that is, the new articles cite this article spread of disease by something in the air. Search for similar articles in: Fracastoro was anticipating, by nearly 350 years, one of the most Science Online important turning points in biological and medical history--the ISI Web of Science consolidation of the germ theory of disease by Louis Pasteur and PubMed Robert Koch in the late 1870s. As we enter the 21st century, Search Medline for articles infectious disease is fated to remain a crucial research challenge, by: one of conceptual intricacy and of global consequence. Lederberg, J. Search for citing articles in: The Incubation of a Scientific Discipline ISI Web of Science (15) Many people laid the groundwork for the germ theory. Even the HighWire Press Journals terrified masses touched by the Black Death (bubonic plague) in Europe after 1346 had some intimation of a contagion at work. -

John Snow: Breaking Barriers for Modern Epidemiology Grace Vance

John Snow: Breaking Barriers for Modern Epidemiology Grace Vance Senior Division Individual Exhibit Student-composed words: 500 Process Paper: 500 Process Paper Considering a future career in Medicine, I knew from the start of my project that something in that field would spark my interest. Since this year’s theme is Breaking Barriers, I also wanted to look for something that was impactful, important, and revolutionary. From my searching came the topic of my dreams: a detective story, a scientific breakthrough, and a historical milestone, all rolled into one. My topic this year is John Snow, and his groundbreaking discoveries in connection with the London Cholera outbreak of 1854. I chose an exhibit board for my presentation because I wanted to include many aspects of my research in both a visual and tangible way. I began my research reading articles introducing me into the field of Epidemiology. I started to look around for biographies, and discovered an insanely helpful collaborative book entitled “Cholera, Chloroform, and the Science of Medicine: a Life of John Snow.” Other helpful sources included UCLA and Michigan State’s epidemiology department websites. These websites gave me access to many primary source documents written by Snow himself. One of the changes I had to make during the duration of my project was narrowing down my thesis. John Snow, being the scientific man he was, was extremely qualified in both the fields of anesthesia/vapors and epidemiology, so I had to pick one or the other to focus on. After deciding to narrow down on his epidemiological work, I had to decide which discovery of his was the most impactful to the world. -

Human Genetic Basis of Interindividual Variability in the Course of Infection

Human genetic basis of interindividual variability in the course of infection Jean-Laurent Casanovaa,b,c,d,e,1 aSt. Giles Laboratory of Human Genetics of Infectious Diseases, Rockefeller Branch, The Rockefeller University, New York, NY 10065; bHoward Hughes Medical Institute, New York, NY 10065; cLaboratory of Human Genetics of Infectious Diseases, Necker Branch, Inserm U1163, Necker Hospital for Sick Children, 75015 Paris, France; dImagine Institute, Paris Descartes University, 75015 Paris, France; and ePediatric Hematology and Immunology Unit, Assistance Publique–Hôpitaux de Paris, Necker Hospital for Sick Children, 75015 Paris, France This contribution is part of the special series of Inaugural Articles by members of the National Academy of Sciences elected in 2015. Contributed by Jean-Laurent Casanova, November 2, 2015 (sent for review September 15, 2015; reviewed by Max D. Cooper and Richard A. Gatti) The key problem in human infectious diseases was posed at the immunity (cell-autonomous mechanisms), then of cell-extrinsic turn of the 20th century: their pathogenesis. For almost any given innate immunity (phagocytosis of pathogens by professional cells), virus, bacterium, fungus, or parasite, life-threatening clinical disease and, finally, of cell-extrinsic adaptive immunity (somatic di- develops in only a small minority of infected individuals. Solving this versification of antigen-specific cells). Understanding the patho- infection enigma is important clinically, for diagnosis, prognosis, genesis of infectious diseases, particularly -

Biotechnology Timeline

Biotechnology Timeline 8000-4000 B.C.E. Humans domesticate crops and livestock. Potatoes first cultivated for food. Biotechnology Timeline 2000 B.C.E. Biotechnology used to leaven bread and ferment beer, using yeast (Egypt). Production of cheese, fermentation of wine begins (Sumeria, China, Egypt). Biotechnology Timeline 500 B.C.E. First antibiotic: Moldy soybean curds (tofu) used to treat boils (China). Biotechnology Timeline 100 C.E. First insecticide: powdered chrysanthemums (China) Biotechnology Timeline 1797 First vaccination Edward Jenner takes pus from a cowpox lesion, inserts it into an incision on a boy's arm. Biotechnology Timeline 1830-1833 1830 Proteins are discovered. Model of a 5-peptide protein. 1833 First enzyme is discovered and isolated. Biotechnology Timeline 1857 Louis Pasteur proposes that microbes cause fermentation. He later conducts experiments that support the germ theory of disease. Biotechnology Timeline 1859 Charles Darwin publishes the theory of evolution by natural selection. Biotechnology Timeline 1865 Gregor Mendel discovers the laws of inheritance by studying flowers in his garden. The science of genetics begins. Biotechnology Timeline 1915 Phages — viruses that only infect bacteria — are discovered. Biotechnology Timeline 1927 Herman Muller discovers that radiation causes defects in chromosomes. Biotechnology Timeline 1928 Sir Alexander Fleming discovers the antibiotic penicillin by chance when he realizes that Penicillium mold kills bacteria. He shared the 1945 Nobel Prize in Medicine with Ernst Boris Chain and Sir Howard Walter Florey. Biotechnology Timeline 1944 DNA is proven to carry genetic information by Oswald Avery, Colin MacLeod and Maclyn McCarty. DNA model made out of LEGOs. Biotechnology Timeline 1953 James Watson and Francis Crick describe the double helical structure of DNA.