Lab Session 02 Objective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lecture Notes in Assembly Language

Lecture Notes in Assembly Language Short introduction to low-level programming Piotr Fulmański Łódź, 12 czerwca 2015 Spis treści Spis treści iii 1 Before we begin1 1.1 Simple assembler.................................... 1 1.1.1 Excercise 1 ................................... 2 1.1.2 Excercise 2 ................................... 3 1.1.3 Excercise 3 ................................... 3 1.1.4 Excercise 4 ................................... 5 1.1.5 Excercise 5 ................................... 6 1.2 Improvements, part I: addressing........................... 8 1.2.1 Excercise 6 ................................... 11 1.3 Improvements, part II: indirect addressing...................... 11 1.4 Improvements, part III: labels............................. 18 1.4.1 Excercise 7: find substring in a string .................... 19 1.4.2 Excercise 8: improved polynomial....................... 21 1.5 Improvements, part IV: flag register ......................... 23 1.6 Improvements, part V: the stack ........................... 24 1.6.1 Excercise 12................................... 26 1.7 Improvements, part VI – function stack frame.................... 29 1.8 Finall excercises..................................... 34 1.8.1 Excercise 13................................... 34 1.8.2 Excercise 14................................... 34 1.8.3 Excercise 15................................... 34 1.8.4 Excercise 16................................... 34 iii iv SPIS TREŚCI 1.8.5 Excercise 17................................... 34 2 First program 37 2.1 Compiling, -

Introduction to X86 Assembly

CS342 Computer Security Handout # 5 Prof. Lyn Turbak Monday, Oct. 04, 2010 Wellesley College Lab 4: Introduction to x86 Assembly Reading: Hacking, 0x250, 0x270 Overview Today, we continue to cover low-level programming details that are essential for understanding software vulnerabilities like buffer overflow attacks and format string exploits. You will get exposure to the following: • Understanding conventions used by compiler to translate high-level programs to low-level assembly code (in our case, using Gnu C Compiler (gcc) to compile C programs). • The ability to read low-level assembly code (in our case, Intel x86). • Understanding how assembly code instructions are represented as machine code. • Being able to use gdb (the Gnu Debugger) to read the low-level code produced by gcc and understand its execution. In tutorials based on this handout, we will learn about all of the above in the context of some simple examples. Intel x86 Assembly Language Since Intel x86 processors are ubiquitous, it is helpful to know how to read assembly code for these processors. We will use the following terms: byte refers to 8-bit quantities; short word refers to 16-bit quantities; word refers to 32-bit quantities; and long word refers to 64-bit quantities. There are many registers, but we mostly care about the following: • EAX, EBX, ECX, EDX are 32-bit registers used for general storage. • ESI and EDI are 32-bit indexing registers that are sometimes used for general storage. • ESP is the 32-bit register for the stack pointer, which holds the address of the element currently at the top of the stack. -

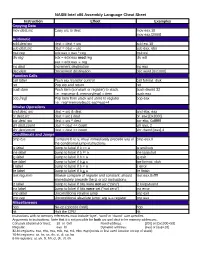

NASM Intel X86 Assembly Language Cheat Sheet

NASM Intel x86 Assembly Language Cheat Sheet Instruction Effect Examples Copying Data mov dest,src Copy src to dest mov eax,10 mov eax,[2000] Arithmetic add dest,src dest = dest + src add esi,10 sub dest,src dest = dest – src sub eax, ebx mul reg edx:eax = eax * reg mul esi div reg edx = edx:eax mod reg div edi eax = edx:eax reg inc dest Increment destination inc eax dec dest Decrement destination dec word [0x1000] Function Calls call label Push eip, transfer control call format_disk ret Pop eip and return ret push item Push item (constant or register) to stack. push dword 32 I.e.: esp=esp-4; memory[esp] = item push eax pop [reg] Pop item from stack and store to register pop eax I.e.: reg=memory[esp]; esp=esp+4 Bitwise Operations and dest, src dest = src & dest and ebx, eax or dest,src dest = src | dest or eax,[0x2000] xor dest, src dest = src ^ dest xor ebx, 0xfffffff shl dest,count dest = dest << count shl eax, 2 shr dest,count dest = dest >> count shr dword [eax],4 Conditionals and Jumps cmp b,a Compare b to a; must immediately precede any of cmp eax,0 the conditional jump instructions je label Jump to label if b == a je endloop jne label Jump to label if b != a jne loopstart jg label Jump to label if b > a jg exit jge label Jump to label if b > a jge format_disk jl label Jump to label if b < a jl error jle label Jump to label if b < a jle finish test reg,imm Bitwise compare of register and constant; should test eax,0xffff immediately precede the jz or jnz instructions jz label Jump to label if bits were not set (“zero”) jz looparound jnz label Jump to label if bits were set (“not zero”) jnz error jmp label Unconditional relative jump jmp exit jmp reg Unconditional absolute jump; arg is a register jmp eax Miscellaneous nop No-op (opcode 0x90) nop hlt Halt the CPU hlt Instructions with no memory references must include ‘byte’, ‘word’ or ‘dword’ size specifier. -

X86 Disassembly Exploring the Relationship Between C, X86 Assembly, and Machine Code

x86 Disassembly Exploring the relationship between C, x86 Assembly, and Machine Code PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Sat, 07 Sep 2013 05:04:59 UTC Contents Articles Wikibooks:Collections Preface 1 X86 Disassembly/Cover 3 X86 Disassembly/Introduction 3 Tools 5 X86 Disassembly/Assemblers and Compilers 5 X86 Disassembly/Disassemblers and Decompilers 10 X86 Disassembly/Disassembly Examples 18 X86 Disassembly/Analysis Tools 19 Platforms 28 X86 Disassembly/Microsoft Windows 28 X86 Disassembly/Windows Executable Files 33 X86 Disassembly/Linux 48 X86 Disassembly/Linux Executable Files 50 Code Patterns 51 X86 Disassembly/The Stack 51 X86 Disassembly/Functions and Stack Frames 53 X86 Disassembly/Functions and Stack Frame Examples 57 X86 Disassembly/Calling Conventions 58 X86 Disassembly/Calling Convention Examples 64 X86 Disassembly/Branches 74 X86 Disassembly/Branch Examples 83 X86 Disassembly/Loops 87 X86 Disassembly/Loop Examples 92 Data Patterns 95 X86 Disassembly/Variables 95 X86 Disassembly/Variable Examples 101 X86 Disassembly/Data Structures 103 X86 Disassembly/Objects and Classes 108 X86 Disassembly/Floating Point Numbers 112 X86 Disassembly/Floating Point Examples 119 Difficulties 121 X86 Disassembly/Code Optimization 121 X86 Disassembly/Optimization Examples 124 X86 Disassembly/Code Obfuscation 132 X86 Disassembly/Debugger Detectors 137 Resources and Licensing 139 X86 Disassembly/Resources 139 X86 Disassembly/Licensing 141 X86 Disassembly/Manual of Style 141 References Article Sources and Contributors 142 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 143 Article Licenses License 144 Wikibooks:Collections Preface 1 Wikibooks:Collections Preface This book was created by volunteers at Wikibooks (http:/ / en. -

Palmtree: Learning an Assembly Language Model for Instruction Embedding

PalmTree: Learning an Assembly Language Model for Instruction Embedding Xuezixiang Li Yu Qu Heng Yin University of California Riverside University of California Riverside University of California Riverside Riverside, CA 92521, USA Riverside, CA 92521, USA Riverside, CA 92521, USA [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT into a neural network (e.g., the work by Shin et al. [37], UDiff [23], Deep learning has demonstrated its strengths in numerous binary DeepVSA [14], and MalConv [35]), or feed manually-designed fea- analysis tasks, including function boundary detection, binary code tures (e.g., Gemini [40] and Instruction2Vec [41]), or automatically search, function prototype inference, value set analysis, etc. When learn to generate a vector representation for each instruction using applying deep learning to binary analysis tasks, we need to decide some representation learning models such as word2vec (e.g., In- what input should be fed into the neural network model. More nerEye [43] and EKLAVYA [5]), and then feed the representations specifically, we need to answer how to represent an instruction ina (embeddings) into the downstream models. fixed-length vector. The idea of automatically learning instruction Compared to the first two choices, automatically learning representations is intriguing, but the existing schemes fail to capture instruction-level representation is more attractive for two reasons: the unique characteristics of disassembly. These schemes ignore the (1) it avoids manually designing efforts, which require expert knowl- complex intra-instruction structures and mainly rely on control flow edge and may be tedious and error-prone; and (2) it can learn higher- in which the contextual information is noisy and can be influenced level features rather than pure syntactic features and thus provide by compiler optimizations. -

X86 Assembly Language Reference Manual

x86 Assembly Language Reference Manual Part No: 817–5477–11 March 2010 Copyright ©2010 Oracle and/or its affiliates. All rights reserved. This software and related documentation are provided under a license agreement containing restrictions on use and disclosure and are protected by intellectual property laws. Except as expressly permitted in your license agreement or allowed by law, you may not use, copy, reproduce, translate, broadcast, modify, license, transmit, distribute, exhibit, perform, publish, or display any part, in any form, or by any means. Reverse engineering, disassembly, or decompilation of this software, unless required by law for interoperability, is prohibited. The information contained herein is subject to change without notice and is not warranted to be error-free. If you find any errors, please report them to us in writing. If this is software or related software documentation that is delivered to the U.S. Government or anyone licensing it on behalf of the U.S. Government, the following notice is applicable: U.S. GOVERNMENT RIGHTS Programs, software, databases, and related documentation and technical data delivered to U.S. Government customers are “commercial computer software” or “commercial technical data” pursuant to the applicable Federal Acquisition Regulation and agency-specific supplemental regulations. As such, the use, duplication, disclosure, modification, and adaptation shall be subject to the restrictions and license terms setforth in the applicable Government contract, and, to the extent applicable by the terms of the Government contract, the additional rights set forth in FAR 52.227-19, Commercial Computer Software License (December 2007). Oracle USA, Inc., 500 Oracle Parkway, Redwood City, CA 94065. -

Intel X86 Assembly Language & Microarchitecture

Intel x86 Assembly Language & Microarchitecture #x86 Table of Contents About 1 Chapter 1: Getting started with Intel x86 Assembly Language & Microarchitecture 2 Remarks 2 Examples 2 x86 Assembly Language 2 x86 Linux Hello World Example 3 Chapter 2: Assemblers 6 Examples 6 Microsoft Assembler - MASM 6 Intel Assembler 6 AT&T assembler - as 7 Borland's Turbo Assembler - TASM 7 GNU assembler - gas 7 Netwide Assembler - NASM 8 Yet Another Assembler - YASM 9 Chapter 3: Calling Conventions 10 Remarks 10 Resources 10 Examples 10 32-bit cdecl 10 Parameters 10 Return Value 11 Saved and Clobbered Registers 11 64-bit System V 11 Parameters 11 Return Value 11 Saved and Clobbered Registers 11 32-bit stdcall 12 Parameters 12 Return Value 12 Saved and Clobbered Registers 12 32-bit, cdecl — Dealing with Integers 12 As parameters (8, 16, 32 bits) 12 As parameters (64 bits) 12 As return value 13 32-bit, cdecl — Dealing with Floating Point 14 As parameters (float, double) 14 As parameters (long double) 14 As return value 15 64-bit Windows 15 Parameters 15 Return Value 16 Saved and Clobbered Registers 16 Stack alignment 16 32-bit, cdecl — Dealing with Structs 16 Padding 16 As parameters (pass by reference) 17 As parameters (pass by value) 17 As return value 17 Chapter 4: Control Flow 19 Examples 19 Unconditional jumps 19 Relative near jumps 19 Absolute indirect near jumps 19 Absolute far jumps 19 Absolute indirect far jumps 20 Missing jumps 20 Testing conditions 20 Flags 21 Non-destructive tests 21 Signed and unsigned tests 22 Conditional jumps 22 Synonyms and terminology 22 Equality 22 Greater than 23 Less than 24 Specific flags 24 One more conditional jump (extra one) 25 Test arithmetic relations 25 Unsigned integers 25 Signed integers 26 a_label 26 Synonyms 27 Signed unsigned companion codes 27 Chapter 5: Converting decimal strings to integers 28 Remarks 28 Examples 28 IA-32 assembly, GAS, cdecl calling convention 28 MS-DOS, TASM/MASM function to read a 16-bit unsigned integer 29 Read a 16-bit unsigned integer from input. -

MARIE: an Introduction to a Simple Computer

00068_CH04_Null.qxd 10/18/10 12:03 PM Page 195 “When you wish to produce a result by means of an instrument, do not allow yourself to complicate it.” —Leonardo da Vinci CHAPTER MARIE: An Introduction 4 to a Simple Computer 4.1 INTRODUCTION esigning a computer nowadays is a job for a computer engineer with plenty of Dtraining. It is impossible in an introductory textbook such as this (and in an introductory course in computer organization and architecture) to present every- thing necessary to design and build a working computer such as those we can buy today. However, in this chapter, we first look at a very simple computer called MARIE: a Machine Architecture that is Really Intuitive and Easy. We then pro- vide brief overviews of Intel and MIPs machines, two popular architectures reflecting the CISC and RISC design philosophies. The objective of this chapter is to give you an understanding of how a computer functions. We have, therefore, kept the architecture as uncomplicated as possible, following the advice in the opening quote by Leonardo da Vinci. 4.2 CPU BASICS AND ORGANIZATION From our studies in Chapter 2 (data representation) we know that a computer must manipulate binary-coded data. We also know from Chapter 3 that memory is used to store both data and program instructions (also in binary). Somehow, the program must be executed and the data must be processed correctly. The central processing unit (CPU) is responsible for fetching program instructions, decod- ing each instruction that is fetched, and performing the indicated sequence of operations on the correct data. -

X86 Assembly Language Reference Manual

x86 Assembly Language Reference Manual Sun Microsystems, Inc. 901 N. San Antonio Road Palo Alto, CA 94303-4900 U.S.A. Part No: 805-4693-10 October 1998 Copyright 1998 Sun Microsystems, Inc. 901 San Antonio Road, Palo Alto, California 94303-4900 U.S.A. All rights reserved. This product or document is protected by copyright and distributed under licenses restricting its use, copying, distribution, and decompilation. No part of this product or document may be reproduced in any form by any means without prior written authorization of Sun and its licensors, if any. Third-party software, including font technology, is copyrighted and licensed from Sun suppliers. Parts of the product may be derived from Berkeley BSD systems, licensed from the University of California. UNIX is a registered trademark in the U.S. and other countries, exclusively licensed through X/Open Company, Ltd. Sun, Sun Microsystems, the Sun logo, SunDocs, Java, the Java Coffee Cup logo, and Solaris are trademarks, registered trademarks, or service marks of Sun Microsystems, Inc. in the U.S. and other countries. All SPARC trademarks are used under license and are trademarks or registered trademarks of SPARC International, Inc. in the U.S. and other countries. Products bearing SPARC trademarks are based upon an architecture developed by Sun Microsystems, Inc. The OPEN LOOK and SunTM Graphical User Interface was developed by Sun Microsystems, Inc. for its users and licensees. Sun acknowledges the pioneering efforts of Xerox in researching and developing the concept of visual or graphical user interfaces for the computer industry. Sun holds a non-exclusive license from Xerox to the Xerox Graphical User Interface, which license also covers Sun’s licensees who implement OPEN LOOK GUIs and otherwise comply with Sun’s written license agreements. -

Modern X86 Assembly Language Programming

Modern X86 Assembly Language Programming 32-bit, 64-bit, SSE, and AVX Daniel Kusswurm Modern X86 Assembly Language Programming: 32-bit, 64-bit, SSE, and AVX Copyright © 2014 by Daniel Kusswurm This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. Exempted from this legal reservation are brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis or material supplied specifically for the purpose of being entered and executed on a computer system, for exclusive use by the purchaser of the work. Duplication of this publication or parts thereof is permitted only under the provisions of the Copyright Law of the Publisher’s location, in its current version, and permission for use must always be obtained from Springer. Permissions for use may be obtained through RightsLink at the Copyright Clearance Center. Violations are liable to prosecution under the respective Copyright Law. ISBN-13 (pbk): 978-1-4842-0065-0 ISBN-13 (electronic): 978-1-4842-0064-3 Trademarked names, logos, and images may appear in this book. Rather than use a trademark symbol with every occurrence of a trademarked name, logo, or image we use the names, logos, and images only in an editorial fashion and to the benefit of the trademark owner, with no intention of infringement of the trademark. -

Intel X86 Assembly Language Cheat Sheet

Intel x86 Assembly Language Cheat Sheet Instruction Effect Examples Copying Data mov src,dest Copy src to dest mov $10,%eax movw %eax,(2000) Arithmetic add src,dest dest = dest + src add $10, %esi sub src,dest dest = dest – src sub %eax,%ebx mul reg edx:eax = eax * reg mul %esi div reg edx = edx:eax mod reg div %edi eax = edx:eax reg inc dest Increment destination inc %eax dec dest Decrement destination dec (0x1000) Function Calls call label Push eip, transfer control call format_disk ret Pop eip and return ret push item Push item (constant or register) to stack pushl $32 push %eax pop [reg] Pop item from stack; optionally store to register pop %eax popl Bitwise Operations and src,dest dest = src & dest and %ebx, %eax or src,dest dest = src | dest orl (0x2000),%eax xor src,dest dest = src ^ dest xor $0xffffffff,%ebx shl count,dest dest = dest << count shl $2,%eax shr count,dest dest = dest >> count shr $4,(%eax) Conditionals and Jumps cmp arg1,arg2 Compare arg1 to arg2; must immediately precede cmp $0,%eax any of the conditional jump instructions je label Jump to label if arg1 == arg2 je endloop jne label Jump to label if arg1 != arg2 jne loopstart jg label Jump to label if arg2 > arg1 jg exit jge label Jump to label if arg2 > arg1 jge format_disk jl label Jump to label if arg2 < arg1 jl error jle label Jump to label if arg2 < arg1 jle finish test reg,imm Bitwise compare of register and constant; must test $0xffff,%eax immediately precede the jz or jnz instructions jz label Jump to label if bits were not set (“zero”) jz looparound jnz label Jump to label if bits were set (“not zero”) jnz error jmp label Unconditional relative jump jmp exit jmp *reg Unconditional absolute jump; arg is a register jmp *%eax ljmp segment,offs Unconditional absolute far jump ljmp $0x10,$0 Miscellaneous nop No-op (opcode 0x90) nop hlt Halt the CPU hlt Suffixes: b=byte (8 bits); w=word (16 bits); l=long (32 bits). -

Intel X86 Assembly Fundamentals

Intel x86 Assembly Fundamentals Comppgzuter Organization and Assembly ygg Languages Yung-Yu Chuang with slides by Kip Irvine x86 Assembly Language Fundamentals Instructions • Assembled into machine code by assembler • Executed at runtime by the CPU • Member of the Intel IA-32 instruction set • Four parts – Label (optional) – Mnemonic (required) – Operand (usually required) – Comment (optional) Label: Mnemonic Operand(s) ;Comment 3 Labels • Act as place markers – marks the address (offset) of code and data • Easier to memorize and more flexible mov ax, [0020] → mov ax, val • Follow identifier rules • Data lbllabel – must be unique –example: myArray BYTE 10 • Code label (ends with a colon) – target of jump and loop instructions –example: L1: mov ax, bx ... jmp L1 4 Reserved words and identifiers • Reserved words cannot be used as identifiers – Instruction mnemonics, directives, type attributes, operators, predefined symbols • Identifiers – 1-247 characters, including digits – case insensitive (by default) – first character must be a letter, _, @, or $ –examples: var1 Count $first _main MAX open_file @@myfile xVal _12345 5 Mnemonics and operands • Instruction mnemonics – "reminder" –examples: MOV, ADD, SUB, MUL, INC, DEC • Operands – constant (immediate value), 96 – constant expression, 2+4 –Register, eax –memoryy( (data label ), coun t • Number of operands: 0 to 3 – stc ; set Carry flag – inc ax ; add 1 to ax – mov count, bx ; move BX to count 6 Directives • Commands that are recognized and acted upon by the assembler – Part of assembler’s