Introduction to X86 Assembly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lecture Notes in Assembly Language

Lecture Notes in Assembly Language Short introduction to low-level programming Piotr Fulmański Łódź, 12 czerwca 2015 Spis treści Spis treści iii 1 Before we begin1 1.1 Simple assembler.................................... 1 1.1.1 Excercise 1 ................................... 2 1.1.2 Excercise 2 ................................... 3 1.1.3 Excercise 3 ................................... 3 1.1.4 Excercise 4 ................................... 5 1.1.5 Excercise 5 ................................... 6 1.2 Improvements, part I: addressing........................... 8 1.2.1 Excercise 6 ................................... 11 1.3 Improvements, part II: indirect addressing...................... 11 1.4 Improvements, part III: labels............................. 18 1.4.1 Excercise 7: find substring in a string .................... 19 1.4.2 Excercise 8: improved polynomial....................... 21 1.5 Improvements, part IV: flag register ......................... 23 1.6 Improvements, part V: the stack ........................... 24 1.6.1 Excercise 12................................... 26 1.7 Improvements, part VI – function stack frame.................... 29 1.8 Finall excercises..................................... 34 1.8.1 Excercise 13................................... 34 1.8.2 Excercise 14................................... 34 1.8.3 Excercise 15................................... 34 1.8.4 Excercise 16................................... 34 iii iv SPIS TREŚCI 1.8.5 Excercise 17................................... 34 2 First program 37 2.1 Compiling, -

Linux Boot Loaders Compared

Linux Boot Loaders Compared L.C. Benschop May 29, 2003 Copyright c 2002, 2003, L.C. Benschop, Eindhoven, The Netherlands. Per- mission is granted to make verbatim copies of this document. This is version 1.1 which has some minor corrections. Contents 1 introduction 2 2 How Boot Loaders Work 3 2.1 What BIOS does for us . 3 2.2 Parts of a boot loader . 6 2.2.1 boot sector program . 6 2.2.2 second stage of boot loader . 7 2.2.3 Boot loader installer . 8 2.3 Loading the operating system . 8 2.3.1 Loading the Linux kernel . 8 2.3.2 Chain loading . 10 2.4 Configuring the boot loader . 10 3 Example Installations 11 3.1 Example root file system and kernel . 11 3.2 Linux Boot Sector . 11 3.3 LILO . 14 3.4 GNU GRUB . 15 3.5 SYSLINUX . 18 3.6 LOADLIN . 19 3.7 Where Can Boot Loaders Live . 21 1 4 RAM Disks 22 4.1 Living without a RAM disk . 22 4.2 RAM disk devices . 23 4.3 Loading a RAM disk at boot time . 24 4.4 The initial RAM disk . 24 5 Making Diskette Images without Diskettes 25 6 Hard Disk Installation 26 7 CD-ROM Installation 29 8 Conclusions 31 1 introduction If you use Linux on a production system, you will only see it a few times a year. If you are a hobbyist who compiles many kernels or who uses many operating systems, you may see it several times per day. -

GNU MP the GNU Multiple Precision Arithmetic Library Edition 6.2.1 14 November 2020

GNU MP The GNU Multiple Precision Arithmetic Library Edition 6.2.1 14 November 2020 by Torbj¨ornGranlund and the GMP development team This manual describes how to install and use the GNU multiple precision arithmetic library, version 6.2.1. Copyright 1991, 1993-2016, 2018-2020 Free Software Foundation, Inc. Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.3 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation; with no Invariant Sections, with the Front-Cover Texts being \A GNU Manual", and with the Back-Cover Texts being \You have freedom to copy and modify this GNU Manual, like GNU software". A copy of the license is included in Appendix C [GNU Free Documentation License], page 132. i Table of Contents GNU MP Copying Conditions :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 1 1 Introduction to GNU MP ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 2 1.1 How to use this Manual :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 2 2 Installing GMP ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 3 2.1 Build Options:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 3 2.2 ABI and ISA :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 8 2.3 Notes for Package Builds:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 11 2.4 Notes for Particular Systems :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 12 2.5 Known Build Problems ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 14 2.6 Performance -

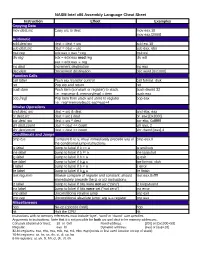

NASM Intel X86 Assembly Language Cheat Sheet

NASM Intel x86 Assembly Language Cheat Sheet Instruction Effect Examples Copying Data mov dest,src Copy src to dest mov eax,10 mov eax,[2000] Arithmetic add dest,src dest = dest + src add esi,10 sub dest,src dest = dest – src sub eax, ebx mul reg edx:eax = eax * reg mul esi div reg edx = edx:eax mod reg div edi eax = edx:eax reg inc dest Increment destination inc eax dec dest Decrement destination dec word [0x1000] Function Calls call label Push eip, transfer control call format_disk ret Pop eip and return ret push item Push item (constant or register) to stack. push dword 32 I.e.: esp=esp-4; memory[esp] = item push eax pop [reg] Pop item from stack and store to register pop eax I.e.: reg=memory[esp]; esp=esp+4 Bitwise Operations and dest, src dest = src & dest and ebx, eax or dest,src dest = src | dest or eax,[0x2000] xor dest, src dest = src ^ dest xor ebx, 0xfffffff shl dest,count dest = dest << count shl eax, 2 shr dest,count dest = dest >> count shr dword [eax],4 Conditionals and Jumps cmp b,a Compare b to a; must immediately precede any of cmp eax,0 the conditional jump instructions je label Jump to label if b == a je endloop jne label Jump to label if b != a jne loopstart jg label Jump to label if b > a jg exit jge label Jump to label if b > a jge format_disk jl label Jump to label if b < a jl error jle label Jump to label if b < a jle finish test reg,imm Bitwise compare of register and constant; should test eax,0xffff immediately precede the jz or jnz instructions jz label Jump to label if bits were not set (“zero”) jz looparound jnz label Jump to label if bits were set (“not zero”) jnz error jmp label Unconditional relative jump jmp exit jmp reg Unconditional absolute jump; arg is a register jmp eax Miscellaneous nop No-op (opcode 0x90) nop hlt Halt the CPU hlt Instructions with no memory references must include ‘byte’, ‘word’ or ‘dword’ size specifier. -

ECE 598 – Advanced Operating Systems Lecture 2

ECE 598 { Advanced Operating Systems Lecture 2 Vince Weaver http://www.eece.maine.edu/~vweaver [email protected] 15 January 2015 Announcements • Update on room situation (shouldn't be locked anymore, but not much chance of getting a better room) 1 Building Linux by Hand • Check out with git or download tarball: git clone git://git.kernel.org/pub/scm/linux/kernel/git/torvalds/linux.git http://www.kernel.org/pub/linux/kernel/v3.x/ • Configure. make config or make menuconfig Also can copy existing .config and run make oldconfig • Compile. 2 make What does make -j 8 do differently? • Make the modules. make modules • sudo make modules install • copy bzImage to boot, update boot loader 3 Building Linux Automated • If in a distro there are other commands to building a package. • For example on Debian make-kpkg --initrd --rootcmd fakeroot kernel image • Then dpkg -i to install; easier to track 4 Overhead (i.e. why not to do it natively on a Pi) • Size { clean git source tree (x86) 1.8GB, compiled with kernel, 2.5GB, compiled kernel with debug features (x86), 12GB!!! Tarball version with compiled kernel (ARM) 1.5GB • Time to compile { minutes (on fast multicore x86 machine) to hours (18 hours or so on Pi) 5 Linux on the Pi • Mainline kernel, bcm2835 tree Missing some features • Raspberry-pi foundation bcm2708 tree More complete, not upstream 6 Compiling { how does it work? • Take C-code • Turn into assembler • Run assembler to make object (machine language files). Final addresses not necessarily put into place • Run linker (which uses linker script) • Makes some sort of executable. -

IT Acronyms.Docx

List of computing and IT abbreviations /.—Slashdot 1GL—First-Generation Programming Language 1NF—First Normal Form 10B2—10BASE-2 10B5—10BASE-5 10B-F—10BASE-F 10B-FB—10BASE-FB 10B-FL—10BASE-FL 10B-FP—10BASE-FP 10B-T—10BASE-T 100B-FX—100BASE-FX 100B-T—100BASE-T 100B-TX—100BASE-TX 100BVG—100BASE-VG 286—Intel 80286 processor 2B1Q—2 Binary 1 Quaternary 2GL—Second-Generation Programming Language 2NF—Second Normal Form 3GL—Third-Generation Programming Language 3NF—Third Normal Form 386—Intel 80386 processor 1 486—Intel 80486 processor 4B5BLF—4 Byte 5 Byte Local Fiber 4GL—Fourth-Generation Programming Language 4NF—Fourth Normal Form 5GL—Fifth-Generation Programming Language 5NF—Fifth Normal Form 6NF—Sixth Normal Form 8B10BLF—8 Byte 10 Byte Local Fiber A AAT—Average Access Time AA—Anti-Aliasing AAA—Authentication Authorization, Accounting AABB—Axis Aligned Bounding Box AAC—Advanced Audio Coding AAL—ATM Adaptation Layer AALC—ATM Adaptation Layer Connection AARP—AppleTalk Address Resolution Protocol ABCL—Actor-Based Concurrent Language ABI—Application Binary Interface ABM—Asynchronous Balanced Mode ABR—Area Border Router ABR—Auto Baud-Rate detection ABR—Available Bitrate 2 ABR—Average Bitrate AC—Acoustic Coupler AC—Alternating Current ACD—Automatic Call Distributor ACE—Advanced Computing Environment ACF NCP—Advanced Communications Function—Network Control Program ACID—Atomicity Consistency Isolation Durability ACK—ACKnowledgement ACK—Amsterdam Compiler Kit ACL—Access Control List ACL—Active Current -

CS 331 GDB and X86-64 Assembly Language

CS 331 Spring 2016 GDB and x86-64 Assembly Language I am not a big fan of debuggers for high-level languages. While they are undeniably useful at times, they are no substitute for careful coding. If code is well structured, I usually find it easier to debug analytically (i.e, by staring at it) than by running it through a debugger. In any event, monkey-coding with a debugger is still monkey-coding, and I don’t want to fly in an airplane being guided by monkey-code. The situation in assembly language is quite different. Assembly instructions can be opaque, especially if you aren’t used to programming in assembly language. In addition, I/O at the assembly level is quite complex; printing values at various places in your code is often not an option.. Debuggers are frequently the only way to discover what your code is actually doing. There are nicer assemblers than the gas (gnu assembler) that we will use, but the gas-gdb combination works quite well and is easy to use. In this document we’ll go briefly through the essential commands for gdb. There is more complete documentation available on any of the Linux systems; just type info gdb And, of course, there is no end of documentation online. To assemble your program with hooks for gdb use the hyphen g flag. For example, if your assembly language program is foobar.s you would assemble it wth gcc foobar.s –g –o foobar and then run gdp with gdb foobar You should always have the program visible in an editor that includes line numbers while you run gdb. -

GNU Toolchain for Atmel ARM Embedded Processors

RELEASE NOTES GNU Toolchain for Atmel ARM Embedded Processors Introduction The Atmel ARM GNU Toolchain (5.3.1.487) supports Atmel ARM® devices. The ARM toolchain is based on the free and open-source GCC. This toolchain is built from sources published by ARM's "GNU Tools for ARM Embedded Processors" project at launchpad.net (https://launchpad.net/gcc-arm-embedded). The toolchain includes compiler, assembler, linker, binutils (GCC and binutils), GNU Debugger (GDB with builtin simulator) and Standard C library (newlib, newlib nano). 42368A-MCU-06/2016 Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................... 1 1. Supported Configuration ......................................................... 3 1.1. Supported Hosts ................................................................... 3 1.2. Supported Targets ................................................................. 3 2. Downloading, Installing, and Upgrading ................................. 4 2.1. Downloading/Installing on Windows .......................................... 4 2.2. Downloading/Installing on Linux ............................................... 4 2.3. Downloading/Installing on Mac OS ........................................... 4 2.4. Upgrading ............................................................................ 4 3. Layout and Components ......................................................... 5 3.1. Layout ................................................................................. 5 3.2. Components -

X86 Disassembly Exploring the Relationship Between C, X86 Assembly, and Machine Code

x86 Disassembly Exploring the relationship between C, x86 Assembly, and Machine Code PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Sat, 07 Sep 2013 05:04:59 UTC Contents Articles Wikibooks:Collections Preface 1 X86 Disassembly/Cover 3 X86 Disassembly/Introduction 3 Tools 5 X86 Disassembly/Assemblers and Compilers 5 X86 Disassembly/Disassemblers and Decompilers 10 X86 Disassembly/Disassembly Examples 18 X86 Disassembly/Analysis Tools 19 Platforms 28 X86 Disassembly/Microsoft Windows 28 X86 Disassembly/Windows Executable Files 33 X86 Disassembly/Linux 48 X86 Disassembly/Linux Executable Files 50 Code Patterns 51 X86 Disassembly/The Stack 51 X86 Disassembly/Functions and Stack Frames 53 X86 Disassembly/Functions and Stack Frame Examples 57 X86 Disassembly/Calling Conventions 58 X86 Disassembly/Calling Convention Examples 64 X86 Disassembly/Branches 74 X86 Disassembly/Branch Examples 83 X86 Disassembly/Loops 87 X86 Disassembly/Loop Examples 92 Data Patterns 95 X86 Disassembly/Variables 95 X86 Disassembly/Variable Examples 101 X86 Disassembly/Data Structures 103 X86 Disassembly/Objects and Classes 108 X86 Disassembly/Floating Point Numbers 112 X86 Disassembly/Floating Point Examples 119 Difficulties 121 X86 Disassembly/Code Optimization 121 X86 Disassembly/Optimization Examples 124 X86 Disassembly/Code Obfuscation 132 X86 Disassembly/Debugger Detectors 137 Resources and Licensing 139 X86 Disassembly/Resources 139 X86 Disassembly/Licensing 141 X86 Disassembly/Manual of Style 141 References Article Sources and Contributors 142 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 143 Article Licenses License 144 Wikibooks:Collections Preface 1 Wikibooks:Collections Preface This book was created by volunteers at Wikibooks (http:/ / en. -

Palmtree: Learning an Assembly Language Model for Instruction Embedding

PalmTree: Learning an Assembly Language Model for Instruction Embedding Xuezixiang Li Yu Qu Heng Yin University of California Riverside University of California Riverside University of California Riverside Riverside, CA 92521, USA Riverside, CA 92521, USA Riverside, CA 92521, USA [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT into a neural network (e.g., the work by Shin et al. [37], UDiff [23], Deep learning has demonstrated its strengths in numerous binary DeepVSA [14], and MalConv [35]), or feed manually-designed fea- analysis tasks, including function boundary detection, binary code tures (e.g., Gemini [40] and Instruction2Vec [41]), or automatically search, function prototype inference, value set analysis, etc. When learn to generate a vector representation for each instruction using applying deep learning to binary analysis tasks, we need to decide some representation learning models such as word2vec (e.g., In- what input should be fed into the neural network model. More nerEye [43] and EKLAVYA [5]), and then feed the representations specifically, we need to answer how to represent an instruction ina (embeddings) into the downstream models. fixed-length vector. The idea of automatically learning instruction Compared to the first two choices, automatically learning representations is intriguing, but the existing schemes fail to capture instruction-level representation is more attractive for two reasons: the unique characteristics of disassembly. These schemes ignore the (1) it avoids manually designing efforts, which require expert knowl- complex intra-instruction structures and mainly rely on control flow edge and may be tedious and error-prone; and (2) it can learn higher- in which the contextual information is noisy and can be influenced level features rather than pure syntactic features and thus provide by compiler optimizations. -

X86 Assembly Language Reference Manual

x86 Assembly Language Reference Manual Part No: 817–5477–11 March 2010 Copyright ©2010 Oracle and/or its affiliates. All rights reserved. This software and related documentation are provided under a license agreement containing restrictions on use and disclosure and are protected by intellectual property laws. Except as expressly permitted in your license agreement or allowed by law, you may not use, copy, reproduce, translate, broadcast, modify, license, transmit, distribute, exhibit, perform, publish, or display any part, in any form, or by any means. Reverse engineering, disassembly, or decompilation of this software, unless required by law for interoperability, is prohibited. The information contained herein is subject to change without notice and is not warranted to be error-free. If you find any errors, please report them to us in writing. If this is software or related software documentation that is delivered to the U.S. Government or anyone licensing it on behalf of the U.S. Government, the following notice is applicable: U.S. GOVERNMENT RIGHTS Programs, software, databases, and related documentation and technical data delivered to U.S. Government customers are “commercial computer software” or “commercial technical data” pursuant to the applicable Federal Acquisition Regulation and agency-specific supplemental regulations. As such, the use, duplication, disclosure, modification, and adaptation shall be subject to the restrictions and license terms setforth in the applicable Government contract, and, to the extent applicable by the terms of the Government contract, the additional rights set forth in FAR 52.227-19, Commercial Computer Software License (December 2007). Oracle USA, Inc., 500 Oracle Parkway, Redwood City, CA 94065. -

An ECMA-55 Minimal BASIC Compiler for X86-64 Linux®

Computers 2014, 3, 69-116; doi:10.3390/computers3030069 OPEN ACCESS computers ISSN 2073-431X www.mdpi.com/journal/computers Article An ECMA-55 Minimal BASIC Compiler for x86-64 Linux® John Gatewood Ham Burapha University, Faculty of Informatics, 169 Bangsaen Road, Tambon Saensuk, Amphur Muang, Changwat Chonburi 20131, Thailand; E-mail: [email protected] Received: 24 July 2014; in revised form: 17 September 2014 / Accepted: 1 October 2014 / Published: 1 October 2014 Abstract: This paper describes a new non-optimizing compiler for the ECMA-55 Minimal BASIC language that generates x86-64 assembler code for use on the x86-64 Linux® [1] 3.x platform. The compiler was implemented in C99 and the generated assembly language is in the AT&T style and is for the GNU assembler. The generated code is stand-alone and does not require any shared libraries to run, since it makes system calls to the Linux® kernel directly. The floating point math uses the Single Instruction Multiple Data (SIMD) instructions and the compiler fully implements all of the floating point exception handling required by the ECMA-55 standard. This compiler is designed to be small, simple, and easy to understand for people who want to study a compiler that actually implements full error checking on floating point on x86-64 CPUs even if those people have little programming experience. The generated assembly code is also designed to be simple to read. Keywords: BASIC; compiler; AMD64; INTEL64; EM64T; x86-64; assembly 1. Introduction The Beginner’s All-purpose Symbolic Instruction Code (BASIC) language was invented by John G.