Highlights from the Meeting of the Strategic Advisory Group of Experts (SAGE) on Immunization 22-24 March 2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

For Schools and Parents: K-12 Immunization Requirements

FOR SCHOOLS AND PARENTS: K-12 IMMUNIZATION REQUIREMENTS NJ Department of Health (NJDOH) Vaccine Preventable Disease Program Summary of NJ School Immunization Requirements Listed in the chart below are the minimum required number of doses your child must have to attend a NJ school.* This is strictly a summary document. Exceptions to these requirements (i.e. provisional admission, grace periods, and exemptions) are specified in the Immunization of Pupils in School rules, New Jersey Administrative Code (N.J.A.C. 8:57-4). Please reference the administrative rules for more details https://www.nj.gov/health/cd/imm_requirements/acode/. Additional vaccines are recommended by Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) for optimal protection. For the complete ACIP Recommended Immunization Schedule, please visit http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/index.html. Minimum Number of Doses for Each Vaccine Grade/level child DTaP Polio MMR Varicella Hepatitis Meningococcal Tdap enters school: Diphtheria, Tetanus, acellular Pertussis Inactivated (Measles, (Chickenpox) B (Tetanus, Polio Vaccine Mumps, diphtheria, (IPV) Rubella) acellular pertussis) § | Kindergarten – A total of 4 doses with one of these doses A total of 3 2 doses 1 dose 3 doses None None 1st grade on or after the 4th birthday doses with one OR any 5 doses† of these doses given on or after the 4th birthday ‡ OR any 4 doses nd th † 2 – 5 grade 3 doses 3 doses 2 doses 1 dose 3 doses None See footnote NOTE: Children 7 years of age and older, who have not been previously vaccinated with the primary DTaP series, should receive 3 doses of Td. -

Polio Vaccine May Be Given at the Same Time As Other Paralysis (Can’T Move Arm Or Leg)

POLIO VVPOLIO AAACCINECCINECCINE (_________ W H A T Y O U N E E D T O K N O W ) (_I111 ________What is polio? ) (_I ________Who should get polio ) 333 vaccine and when? Polio is a disease caused by a virus. It enters a child’s (or adult’s) body through the mouth. Sometimes it does IPV is a shot, given in the leg or arm, depending on age. not cause serious illness. But sometimes it causes Polio vaccine may be given at the same time as other paralysis (can’t move arm or leg). It can kill people who vaccines. get it, usually by paralyzing the muscles that help them Children breathe. Most people should get polio vaccine when they are Polio used to be very common in the United States. It children. Children get 4 doses of IPV, at these ages: paralyzed and killed thousands of people a year before we 333 A dose at 2 months 333 A dose at 6-18 months had a vaccine for it. 333 A dose at 4 months 333 A booster dose at 4-6 years 222 Why get vaccinated? ) Adults c I Most adults do not need polio vaccine because they were Inactivated Polio Vaccine (IPV) can prevent polio. already vaccinated as children. But three groups of adults are at higher risk and should consider polio vaccination: History: A 1916 polio epidemic in the United States killed (1) people traveling to areas of the world where polio is 6,000 people and paralyzed 27,000 more. In the early common, 1950’s there were more than 20,000 cases of polio each (2) laboratory workers who might handle polio virus, and year. -

Swine Flu and Polio Vaccines: Some Parallels and Some Differences

Swine Fluand Polio Vaccines: Some Parallelsand Some Differences Howard B. Baumel College of Staten Island of the City Universityof New York Staten Island 10301 The swine flu vaccinationprogram vaccine could be successfullydevel- facturedby a single pharmaceutical generated debate in scientific and oped. company.The cause of this outbreak medical circlesthat extended to the Salkrelied heavily on his previous was never clearly established. Be- Downloaded from http://online.ucpress.edu/abt/article-pdf/39/9/550/36038/4446085.pdf by guest on 29 September 2021 general public.The controversythat experience as he attemptedto pro- cause bottles of tissue culture fluid centered on the vaccine's effective- duce a killedvirus polio vaccine.He containingthe virushad been stored ness and safety was reminiscentof used formalinto kill the virus and priorto being treated with formalin, the problemsthat accompaniedthe isolated one strain for each of the it was possiblethat bits of tissue had development of the polio vaccine three knowntypes of polio virus.To settled to the bottom covering the years ago. A review of that earlier determineif any live virusremained viruses and protecting them from scientific achievement can provide after the exposure to formalin,the the formalin.To prevent this, the insightsinto the swineflu dilemma. treated virus was injected into the tissue culture fluid was filtered to By the mid-1930's,only threeviral brain of a monkey. If the monkey remove the debris before exposure diseases,smallpox, rabies, and yellow contracted polio, it was concluded to formalin. fever, had yielded to vaccines. In that live viruswas present.To deter- HeraldCox and HilaryKoprowski each of these cases, the vaccine mine if the treated virus was effec- (1955, 1956) had developed an consisted of a live virus. -

Polio Fact Sheet

Polio Fact Sheet 1. What is Polio? - Polio is a disease caused by a virus that lives in the human throat and intestinal tract. It is spread by exposure to infected human stool: e.g. from poor sanitation practices. The 1952 Polio epidemic was the worst outbreak in the nation's history. Of nearly 58,000 cases reported that year, 3,145 people died and 21,269 were left with mild to disabling paralysis, with most of the victims being children. The "public reaction was to a plague", said historian William O'Neill. "Citizens of urban areas were to be terrified every summer when this frightful visitor returned.” A Polio vaccine first became available in 1955. 2. What are the symptoms of Polio? - Up to 95 % of people infected with Polio virus are not aware they are infected, but can still transmit it to others. While some develop just a fever, sore throat, upset stomach, and/or flu-like symptoms and have no paralysis or other serious symptoms, others get a stiffness of the back or legs, and experience increased sensitivity. However, a few develop life-threatening paralysis of muscles. The risk of developing serious symptoms increases with the age of the ill person. 3. Is Polio still a disease seen in the United States? - The last naturally occurring cases of Polio in the United States were in 1979, when an outbreak occurred among the Amish in several states including Pennsylvania. 4. What kinds of Polio vaccines are used in the United States? - There is now only one kind of Polio vaccine used in the United States: the Inactivated Polio vaccine (IPV) is given as an injection (shot). -

Evidence Assessment STRATEGIC ADVISORY GROUP of EXPERTS (SAGE) on IMMUNIZATION Meeting 15 March 2021

Evidence Assessment STRATEGIC ADVISORY GROUP OF EXPERTS (SAGE) ON IMMUNIZATION Meeting 15 March 2021 FOR RECOMMENDATION BY SAGE Prepared by the SAGE Working Group on COVID-19 vaccines EVIDENCE ASSESSMENT: Ad26.COV2.S COVID-19 vaccine Key evidence to inform policy recommendations on the use of Ad26.COV2.S COVID-19 vaccine Evidence retrieval • Based on WHO and Cochrane living mapping and living systematic review of Covid-19 trials (www.covid-nma.com/vaccines) Retrieved evidence Majority of data considered for policy recommendations on Ad26.COV2.S Covid-19 vaccine are published in scientific peer reviewed journals: • Interim Results of a Phase 1–2a Trial of Ad26.COV2.S Covid-19 Vaccine. NEJM. February 2021. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa2034201. Jerald Sadoff, Mathieu Le Gars, Georgi Shukarev, et al. • FDA briefing document Janssen Ad26.COV2.S (COVID-19) Vaccine • Ad26 platform literature: Custers et al. Vaccines based on the Ad26 platform; Vaccine 2021 Quality assessment Type of bias Randomization Deviations from Missing outcome Measurement of Selection of the Overall risk of intervention data the outcome reported results bias Working Group Low Low Low Low Low LOW judgment 1 EVIDENCE ASSESSMENT The SAGE Working Group specifically considered the following issues: 1. Trial endpoints used in comparison with other vaccines Saad Omer 2. Evidence on vaccine efficacy in the total population and in different subgroups Cristiana Toscano 3. Evidence of vaccine efficacy against asymptomatic infections, reducing severity, hospitalisations, deaths, and efficacy against virus variants of concern Annelies Wilder-Smith 4. Vaccination after SARS-CoV2 infection. 5. Evidence on vaccine safety in the total population and in different subgroups Sonali Kochhar 6. -

2021-22 School Year New York State Immunization Requirements for School Entrance/Attendance1

2021-22 School Year New York State Immunization Requirements for School Entrance/Attendance1 NOTES: Children in a prekindergarten setting should be age-appropriately immunized. The number of doses depends on the schedule recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). Intervals between doses of vaccine should be in accordance with the ACIP-recommended immunization schedule for persons 0 through 18 years of age. Doses received before the minimum age or intervals are not valid and do not count toward the number of doses listed below. See footnotes for specific information foreach vaccine. Children who are enrolling in grade-less classes should meet the immunization requirements of the grades for which they are age equivalent. Dose requirements MUST be read with the footnotes of this schedule Prekindergarten Kindergarten and Grades Grades Grade Vaccines (Day Care, 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 12 Head Start, and 11 Nursery or Pre-k) Diphtheria and Tetanus 5 doses toxoid-containing vaccine or 4 doses and Pertussis vaccine 4 doses if the 4th dose was received 3 doses (DTaP/DTP/Tdap/Td)2 at 4 years or older or 3 doses if 7 years or older and the series was started at 1 year or older Tetanus and Diphtheria toxoid-containing vaccine Not applicable 1 dose and Pertussis vaccine adolescent booster (Tdap)3 Polio vaccine (IPV/OPV)4 4 doses 3 doses or 3 doses if the 3rd dose was received at 4 years or older Measles, Mumps and 1 dose 2 doses Rubella vaccine (MMR)5 Hepatitis B vaccine6 3 doses 3 doses or 2 doses of adult hepatitis B vaccine (Recombivax) for children who received the doses at least 4 months apart between the ages of 11 through 15 years Varicella (Chickenpox) 1 dose 2 doses vaccine7 Meningococcal conjugate Grades 2 doses vaccine (MenACWY)8 7, 8, 9, 10 or 1 dose Not applicable and 11: if the dose 1 dose was received at 16 years or older Haemophilus influenzae type b conjugate vaccine 1 to 4 doses Not applicable (Hib)9 Pneumococcal Conjugate 1 to 4 doses Not applicable vaccine (PCV)10 Department of Health 1. -

Vaccinations for Preteens and Teens, Age 11-19 Years

Vaccinations for Preteens and Teens, Age 11–19 Years Getting immunized is a lifelong, life-protecting job. Make sure you and your healthcare provider keep your immunizations up to date. Check to be sure you’ve had all the vaccinations you need. Vaccine Do you need it? Chickenpox Yes! If you haven’t been vaccinated and haven’t had chickenpox, you need 2 doses of this vaccine. (varicella; Var) Anybody who was vaccinated with only 1 dose should get a second dose. Hepatitis A Yes! If you haven’t been vaccinated, you need 2 doses of this vaccine. Anybody who was vaccinated (HepA) with only 1 dose should get a second dose at least 6–18 months later. Hepatitis B Yes! This vaccine is recommended for all people age 0–18 years. You need a hepatitis B vaccine series (HepB) if you have not already received it. Haemophilus influ- Maybe. If you haven’t been vaccinated against Hib and have a high-risk condition (such as a non- enzae type b (Hib) functioning spleen), you need this vaccine. Human Yes! All preteens need 2 doses of HPV vaccine at age 11 or 12. Older teens who haven't been vacci- papillomavirus nated will need 2 or 3 doses. This vaccine protects against HPV, a common cause of genital warts and (HPV) several types of cancer, including cervical cancer and cancer of the anus, penis, and throat. Influenza Yes! Everyone age 6 months and older needs annual influenza vaccination every fall or winter and (Flu) for the rest of their lives. -

U.S. Support Essential to Ambitious Global Introduction of Inactivated Polio Vaccine

December 2014 U.S. Support Essential to Ambitious Global Introduction of Inactivated Polio Vaccine Nellie Bristol1 Earlier this fall, Nepal became the first low-income country to introduce the inactivated polio vaccine (IPV) into its immunization system. Many more countries will have to follow suit to meet the ambitious deadlines laid out in the Global Polio Eradication Initiative’s (GPEI)2 Polio Eradication & Endgame Strategic Plan 2013–2018.3 The plan calls for global introduction of at least one dose of IPV into routine childhood immunization schedules followed by eventual withdrawal of the widely used oral polio vaccine (OPV). Currently, 75 mostly high- and middle-income countries use the injectable IPV in their immunization systems, leaving 119 that need to do so by the end of 2015 to keep with the plan’s schedule. The IPV introduction timeline called for in the strategy is extraordinarily quick; most vaccines are incorporated into national routine immunization programs over years if not decades. In calling for universal adoption of IPV over several years, “We’ll be trying to do something that’s never been done in terms of speed,” said Bruce Aylward, the World Health Organization’s assistant director-general for polio and emergencies.4 The move is necessary to complete and sustain global polio eradication. OPV has long been the vaccine of choice for many countries and is used in mass vaccination campaigns. It is inexpensive (as little as 14 cents per dose),5 easy to administer, and provides comprehensive immunity. But it has one serious drawback: since it uses a live, weakened virus, in rare instances, polioviruses in the vaccine can cause the disease. -

Improving the Regulatory Response to Vaccine Development During a Public Health Emergency

Every Minute Matters: Improving the Regulatory Response to Vaccine Development During a Public Health Emergency RASHMI BORAH* ABSTRACT In recent months, our lives have been turned upside down by the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) emergency. With no cure or vaccine in sight, millions of people have contracted the virus, and the death toll has surpassed that of World War I in a fraction of the time. In fact, the past decade has been marked by a series of highly publicized public health emergencies, including the devastating Ebola and Zika virus global outbreaks. Some of this panic arose from a failure to manufacture and distribute vaccines in a timely fashion. This failure occurred despite having several viable vaccine candidates, adequate funding, and strong public support for the vaccines. This Article explains how these failures are the consequence of a complex network of existing regulatory pathways and insufficient incentives to produce affordable vaccinations during a public health emergency. Fortunately, there are several ways that both the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration can improve and streamline the process of patenting, approving, manufacturing, and distributing a vaccination. The last decade has demonstrated that public health emergencies occur quickly, and affected communities cannot afford the delays and mishaps that characterized the vaccine response to COVID-19, Ebola, and Zika. This Article explores three ways to facilitate the development and distribution of vaccinations during a public health emergency. First, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office can establish a dedicated public health emergency patent pathway for vaccine technology developed specifically in response to a public health emergency. -

COVID-19 Vaccines: Summary of Current State-Of-Play Prepared Under Urgency 21 May 2020 – Updated 16 July 2020

Office of the Prime Minister’s Chief Science Advisor Kaitohutohu Mātanga Pūtaiao Matua ki te Pirimia COVID-19 vaccines: Summary of current state-of-play Prepared under urgency 21 May 2020 – updated 16 July 2020 The COVID-19 pandemic has spurred a global effort to find a vaccine to protect people from SARS- CoV-2 infection. This summary highlights selected candidates, explains the different types of vaccines being investigated and outlines some of the potential issues and risks that may arise during the clinical testing process and beyond. Key points • There are at least 22 vaccine candidates registered in clinical (human) trials, out of a total of at least 194 in various stages of active development. • It is too early to choose a particular frontrunner as we lack safety and efficacy information for these candidates. • It is difficult to predict when a vaccine will be widely available. The fastest turnaround from exploratory research to vaccine approval was previously 4–5 years (ebolavirus vaccine), although it is likely that current efforts will break this record. • There are a number of challenges associated with accelerated vaccine development, including ensuring safety, proving efficacy in a rapidly changing pandemic landscape, and scaling up manufacture. • The vaccine that is licensed first will not necessarily confer full or long-lasting protection. 1 Contents Key points .................................................................................................................................. 1 1. Types of vaccines ............................................................................................................... -

Role of Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization (GAVI) in Accelerating Inactivated Polio Vaccine Introduction

P E R S P E C T I V E Role of Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization (GAVI) in Accelerating Inactivated Polio Vaccine Introduction NAVEEN THACKER, #DEEP T HACKER AND #ASHISH PATHAK From Deep Children Hospital and Research Centre, Gandhidham, and #Department of Pediatrics, RD Gardi Medical College, Ujjain, Madhya Pradesh, India. Correspondence to: Dr Ashish Pathak, Professor, Department of Pediatrics, RD Gardi Medical College, Ujjain, Madhya Pradesh, India. [email protected] Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization (GAVI, the Vaccine Alliance) is an international organization built through public-private partnership. GAVI has supported more than 200 vaccine introductions in the last 5 years by financing major proportion of costs of vaccine to 73 low-income countries using a co-financing model. GAVI has worked in close co-ordination with Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) since 2013, to strengthen health systems in countries so as to accelerate introduction of inactivated polio vaccine (IPV). GAVI is involved in many IPV related issues like demand generation, supply, market shaping, communications, country readiness etc. Most of the 73 GAVI eligible countries are also high priority countries for GPEI. GAVI support has helped India to accelerate introduction of IPV in all its states. However, GAVI faces challenges in IPV supply-related issues in the near future. It also needs to play a key role in global polio legacy planning and implementation. Keywords: GAVI, the Vaccine Alliance, Global Polio Eradication Initiative, IPV. lobal Alliance for Vaccines and developed common goals, objectives, oversight Immunization (GAVI, the Vaccine Alliance) mechanisms, accountability mechanism and common is an international organization, which was program management as shown in Fig. -

Candidate SARS-Cov-2 Vaccines in Advanced Clinical Trials: Key Aspects Compiled by John D

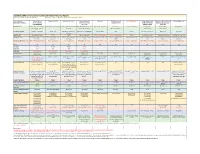

Candidate SARS-CoV-2 Vaccines in Advanced Clinical Trials: Key Aspects Compiled by John D. Grabenstein, RPh, PhD All dates are estimates. All Days are based on first vaccination at Day 0. Vaccine Sponsor Univ. of Oxford ModernaTX USA BioNTech with Pfizer Johnson & Johnson Novavax Sanofi Pasteur with CureVac with Bayer CanSino Biologics with Sinopharm (China National Sinovac Biotech Co. [with Major Partners] (Jenner Institute) (Janssen Vaccines & GlaxoSmithKline Academy of Military Biotec Group) (Beijing IBP, with AstraZeneca Prevention) Medical Sciences Wuhan IBP) Headquarters Oxford, England; Cambridge, Cambridge, Massachusetts Mainz, Germany; New York, New Brunswick, New Jersey Gaithersburg, Maryland Lyon, France; Tübingen, Germany Tianjin, China; Beijing, China; Beijing, China England, Gothenburg, New York (Leiden, Netherlands) Brentford, England Beijing, China Wuhan, China Sweden Product Designator ChAdOx1 or AZD1222 mRNA-1273 BNT162b2, tozinameran, Ad26.COV2.S, JNJ-78436735 NVX-CoV2373 TBA CVnCoV Ad5-nCoV, Convidecia BBIBP-CorV CoronaVac Comirnaty Vaccine Type Adenovirus 63 vector mRNA mRNA Adenovirus 26 vector Subunit (spike) protein Subunit (spike) protein mRNA Adenovirus 5 vector Inactivated whole virus Inactivated whole virus Product Features Chimpanzee adenovirus type Within lipid nanoparticle Within lipid nanoparticle Human adenovirus type 26 Adjuvanted with Matrix-M Adjuvanted with AS03 or Adjuvanted with AS03 Human adenovirus type 5 Adjuvanted with aluminum Adjuvanted with aluminum 63 vector dispersion dispersion vector AF03