XXV TAG Meeting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

XXV TAG Meeting

XXV TAG Meeting Twenty-Fifth Meeting of the Technical Advisory Group (TAG) on Vaccine-preventable Diseases 9-11 July 2019 Cartagena, Colombia 1 TAG Members J. Peter Figueroa TAG Chair Professor of Public Health, Epidemiology & HIV/AIDS University of the West Indies Kingston, Jamaica Jon K. Andrus Adjunct Professor and Senior Investigator Center for Global Health, Division of Vaccines and Immunization University of Colorado Washington, DC, United States Pablo Bonvehi Scientific Director VACUNAR S.A. Buenos Aires, Argentina Roger Glass* Director Fogarty International Center & Associate Director for International Research NIH/JEFIC-National Institutes of Health Bethesda, MD, United States Akira Homma Chairman of Policy and Strategy Council Bio-Manguinhos Institute Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Arlene King Adjunct Professor Dalla Lana School of Public Health University of Toronto Ontario, Canada Nancy Messonnier* Director National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Decatur, GA, United States José Ignacio Santos Secretary. Consejo de Salubridad General Lieja 7, Piso 2, Col. Juárez Delg. Cuauhtémoc, Cd. De México CP 06600 2 Cristiana M. Toscano Head of the Department of Collective Health Institute of Tropical Pathology and Public Health, Federal University of Goiás Goiania, Brazil Cuauhtémoc Ruiz-Matus Ad hoc Secretary Unit Chief Comprehensive Family Immunization PAHO/WHO Washington, DC, United States * Not present at the meeting 3 Table of Contents Contents Acronyms ............................................................................................................................................ -

For Schools and Parents: K-12 Immunization Requirements

FOR SCHOOLS AND PARENTS: K-12 IMMUNIZATION REQUIREMENTS NJ Department of Health (NJDOH) Vaccine Preventable Disease Program Summary of NJ School Immunization Requirements Listed in the chart below are the minimum required number of doses your child must have to attend a NJ school.* This is strictly a summary document. Exceptions to these requirements (i.e. provisional admission, grace periods, and exemptions) are specified in the Immunization of Pupils in School rules, New Jersey Administrative Code (N.J.A.C. 8:57-4). Please reference the administrative rules for more details https://www.nj.gov/health/cd/imm_requirements/acode/. Additional vaccines are recommended by Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) for optimal protection. For the complete ACIP Recommended Immunization Schedule, please visit http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/index.html. Minimum Number of Doses for Each Vaccine Grade/level child DTaP Polio MMR Varicella Hepatitis Meningococcal Tdap enters school: Diphtheria, Tetanus, acellular Pertussis Inactivated (Measles, (Chickenpox) B (Tetanus, Polio Vaccine Mumps, diphtheria, (IPV) Rubella) acellular pertussis) § | Kindergarten – A total of 4 doses with one of these doses A total of 3 2 doses 1 dose 3 doses None None 1st grade on or after the 4th birthday doses with one OR any 5 doses† of these doses given on or after the 4th birthday ‡ OR any 4 doses nd th † 2 – 5 grade 3 doses 3 doses 2 doses 1 dose 3 doses None See footnote NOTE: Children 7 years of age and older, who have not been previously vaccinated with the primary DTaP series, should receive 3 doses of Td. -

Safety of Immunization During Pregnancy a Review of the Evidence

Safety of Immunization during Pregnancy A review of the evidence Global Advisory Committee on Vaccine Safety © World Health Organization 2014 All rights reserved. Publications of the World Health Organization are available on the WHO website (www.who.int) or can be purchased from WHO Press, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland (tel.: +41 22 791 3264; fax: +41 22 791 4857; e-mail: [email protected]). Requests for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications –whether for sale or for non-commercial distribution– should be addressed to WHO Press through the WHO website (www.who.int/about/licensing/copyright_form/en/index.html). The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters. All reasonable precautions have been taken by the World Health Organization to verify the information contained in this publication. However, the published material is being distributed without warranty of any kind, either expressed or implied. -

Pneumococcal Vaccine

Vaccines for Primary Care Pneumococcal, Shingles, Pertussis Devang Patel, M.D. Assistant Professor Chief of Service, MICU ID Service University of Maryland School of Medicine Pneumococcal Vaccine Pneumococcal Disease • 2nd most common cause of vaccine preventable death in the US • Major Syndromes – Pneumonia – Bacteremia – Meningitis Active Bacterial Core Surveillance (ABCs) Report Emerging Infections Program Network Streptococcus pneumoniae, 2010 (ORIG) Vaccine Target • Polysaccharide capsule allows bacteria to resist phagocytosis • Antibodies to capsule facilitate phagocytosis • >90 different pneumococcal capsular serotypes • Vaccines contain most common serotypes causing disease Pneumococcal Vaccines Pneumococcal Vaccines • Pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23; Pneumovax) – Contains capsular polysaccharides – 23 most commonly infecting serotypes • Cause 60% of all pneumococcal infections in adults – Not recommended for children <2 due to poor immunogenicity of polysaccharides Pneumococcal Vaccines • Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13, Prevnar) – Polysaccharides linked to nontoxic protein • higher antigenicity – Stimulates mucosal antibody • Eliminates nasal carriage in young children • Herd effect in adults – Reduction in PCV7 serotype disease >90% Prevnar 13 • 2000 - PCV7 approved for infants toddlers • 2010 - PCV13 recommended for infants and toddlers • 2012 – ACIP recommended PCV13 for high- risk adults • 2014 – recommended for adults >65 • 2018 – ACIP will revisit PCV13 use in adults – Childhood vaccines may eliminate -

Summary Guide to Tetanus Prophylaxis in Routine Wound Management

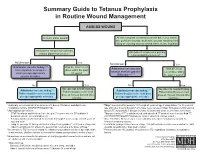

Summary Guide to Tetanus Prophylaxis in Routine Wound Management ASSESS WOUND A clean, minor wound All other wounds (contaminated with dirt, feces, saliva, soil; puncture wounds; avulsions; wounds resulting from flying or crushing objects, animal bites, burns, frostbite) Has patient completed a primary Has patient completed a primary tetanus diphtheria series?1, 7 tetanus diphtheria series?1, 7 No/Unknown Yes No/Unknown Yes Administer vaccine today.2,3,4 Was the most recent Administer vaccine and Was the most Instruct patient to complete dose within the past tetanus immune gobulin recent dose within series per age-appropriate 10 years? (TIG) now.2,4,5,6,7 the past 5 years?7 vaccine schedule. No Yes No Yes Vaccine not needed today. Vaccine not needed today. Administer vaccine today.2,4 2,4 Patient should receive next Administer vaccine today. Patient should receive next Patient should receive next dose Patient should receive next dose dose at 10-year interval after dose at 10-year interval after per age-appropriate schedule. per age-appropriate schedule. last dose. last dose. 1 A primary series consists of a minimum of 3 doses of tetanus- and diphtheria- 4 Tdap* is preferred for persons 11 through 64 years of age if using Adacel* or 10 years of containing vaccine (DTaP/DTP/Tdap/DT/Td). age and older if using Boostrix* who have never received Tdap. Td is preferred to tetanus 2 Age-appropriate vaccine: toxoid (TT) for persons 7 through 9 years, 65 years and older, or who have received a • DTaP for infants and children 6 weeks up to 7 years of age (or DT pediatric if Tdap previously. -

YF-VAX® Rx Only AHFS Category

YF-VAX® Rx Only Laboratory Personnel AHFS Category: 80:12 Laboratory personnel who handle virulent yellow fever virus or concentrated preparations Rx only of the yellow fever vaccine virus strains may be at risk of exposure by direct or indirect Yellow Fever Vaccine contact or by aerosols. (14) DESCRIPTION CONTRAINDICATIONS ® Hypersensitivity YF-VAX , Yellow Fever Vaccine, for subcutaneous use, is prepared by culturing the YF-VAX is contraindicated in anyone with a history of acute hypersensitivity reaction to any 17D-204 strain of yellow fever virus in living avian leukosis virus-free (ALV-free) chicken component of the vaccine. (See DESCRIPTION section.) Because the yellow fever virus embryos. The vaccine contains sorbitol and gelatin as a stabilizer, is lyophilized, and is used in the production of this vaccine is propagated in chicken embryos, do not administer hermetically sealed under nitrogen. No preservative is added. Each vial of vaccine is YF-VAX to anyone with a history of acute hypersensitivity to eggs or egg products due to supplied with a separate vial of sterile diluent, which contains Sodium Chloride Injection a risk of anaphylaxis. Less severe or localized manifestations of allergy to eggs or to USP – without a preservative. YF-VAX is formulated to contain not less than 4.74 log10 feathers are not contraindications to vaccine administration and do not usually warrant plaque forming units (PFU) per 0.5 mL dose throughout the life of the product. Before vaccine skin testing. (See PRECAUTIONS section, Testing for Hypersensitivity Re- reconstitution, YF-VAX is a pinkish color. After reconstitution, YF-VAX is a slight pink-brown actions subsection.) Generally, persons who are able to eat eggs or egg products may suspension. -

PROMOTING INCLUSION THROUGH SOCIAL PROTECTION Report on the World Social Situation 2018 Advanced Copy Advanced Copy ST/ESA/366

Advanced Copy PROMOTING INCLUSION THROUGH SOCIAL PROTECTION Report on the World Social Situation 2018 Advanced Copy Advanced Copy ST/ESA/366 Department of Economic and Social Affairs Promoting Inclusion through Social Protection Report on the World Social Situation 2018 United Nations New York, 2018 Advanced Copy Department of Economic and Social Affairs The Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations Secretariat is a vital interface between global policies in the economic, social and environmental spheres and national action. The Department works in three main interlinked areas: (i) it compiles, generates and analyses a wide range of economic, social and environ- mental data and information on which States Members of the United Nations draw to review common problems and to take stock of policy options; (ii) it facilitates the negotiations of Member States in many intergovernmental bodies on joint courses of action to address ongoing or emerging global challenges; and (iii) it advises interested Governments on the ways and means of translating policy frameworks developed in United Nations conferences and summits into programmes at the country level and, through technical assistance, helps build national capacities. Note The designations employed and the presentation of the material in the present publica- tion do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secre- tariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country or territory or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitations of its frontiers. The term “country” as used in the text of this report also refers, as appropriate, to territories or areas. -

Vaccines for Preteens

| DISEASES and the VACCINES THAT PREVENT THEM | INFORMATION FOR PARENTS Vaccines for Preteens: What Parents Should Know Last updated JANUARY 2017 Why does my child need vaccines now? to get vaccinated. The best time to get the flu vaccine is as soon as it’s available in your community, ideally by October. Vaccines aren’t just for babies. Some of the vaccines that While it’s best to be vaccinated before flu begins causing babies get can wear off as kids get older. And as kids grow up illness in your community, flu vaccination can be beneficial as they may come in contact with different diseases than when long as flu viruses are circulating, even in January or later. they were babies. There are vaccines that can help protect your preteen or teen from these other illnesses. When should my child be vaccinated? What vaccines does my child need? A good time to get these vaccines is during a yearly health Tdap Vaccine checkup. Your preteen or teen can also get these vaccines at This vaccine helps protect against three serious diseases: a physical exam required for sports, school, or camp. It’s a tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis (whooping cough). good idea to ask the doctor or nurse every year if there are any Preteens should get Tdap at age 11 or 12. If your teen didn’t vaccines that your child may need. get a Tdap shot as a preteen, ask their doctor or nurse about getting the shot now. What else should I know about these vaccines? These vaccines have all been studied very carefully and are Meningococcal Vaccine safe. -

Polio Vaccine May Be Given at the Same Time As Other Paralysis (Can’T Move Arm Or Leg)

POLIO VVPOLIO AAACCINECCINECCINE (_________ W H A T Y O U N E E D T O K N O W ) (_I111 ________What is polio? ) (_I ________Who should get polio ) 333 vaccine and when? Polio is a disease caused by a virus. It enters a child’s (or adult’s) body through the mouth. Sometimes it does IPV is a shot, given in the leg or arm, depending on age. not cause serious illness. But sometimes it causes Polio vaccine may be given at the same time as other paralysis (can’t move arm or leg). It can kill people who vaccines. get it, usually by paralyzing the muscles that help them Children breathe. Most people should get polio vaccine when they are Polio used to be very common in the United States. It children. Children get 4 doses of IPV, at these ages: paralyzed and killed thousands of people a year before we 333 A dose at 2 months 333 A dose at 6-18 months had a vaccine for it. 333 A dose at 4 months 333 A booster dose at 4-6 years 222 Why get vaccinated? ) Adults c I Most adults do not need polio vaccine because they were Inactivated Polio Vaccine (IPV) can prevent polio. already vaccinated as children. But three groups of adults are at higher risk and should consider polio vaccination: History: A 1916 polio epidemic in the United States killed (1) people traveling to areas of the world where polio is 6,000 people and paralyzed 27,000 more. In the early common, 1950’s there were more than 20,000 cases of polio each (2) laboratory workers who might handle polio virus, and year. -

Swine Flu and Polio Vaccines: Some Parallels and Some Differences

Swine Fluand Polio Vaccines: Some Parallelsand Some Differences Howard B. Baumel College of Staten Island of the City Universityof New York Staten Island 10301 The swine flu vaccinationprogram vaccine could be successfullydevel- facturedby a single pharmaceutical generated debate in scientific and oped. company.The cause of this outbreak medical circlesthat extended to the Salkrelied heavily on his previous was never clearly established. Be- Downloaded from http://online.ucpress.edu/abt/article-pdf/39/9/550/36038/4446085.pdf by guest on 29 September 2021 general public.The controversythat experience as he attemptedto pro- cause bottles of tissue culture fluid centered on the vaccine's effective- duce a killedvirus polio vaccine.He containingthe virushad been stored ness and safety was reminiscentof used formalinto kill the virus and priorto being treated with formalin, the problemsthat accompaniedthe isolated one strain for each of the it was possiblethat bits of tissue had development of the polio vaccine three knowntypes of polio virus.To settled to the bottom covering the years ago. A review of that earlier determineif any live virusremained viruses and protecting them from scientific achievement can provide after the exposure to formalin,the the formalin.To prevent this, the insightsinto the swineflu dilemma. treated virus was injected into the tissue culture fluid was filtered to By the mid-1930's,only threeviral brain of a monkey. If the monkey remove the debris before exposure diseases,smallpox, rabies, and yellow contracted polio, it was concluded to formalin. fever, had yielded to vaccines. In that live viruswas present.To deter- HeraldCox and HilaryKoprowski each of these cases, the vaccine mine if the treated virus was effec- (1955, 1956) had developed an consisted of a live virus. -

Polio Fact Sheet

Polio Fact Sheet 1. What is Polio? - Polio is a disease caused by a virus that lives in the human throat and intestinal tract. It is spread by exposure to infected human stool: e.g. from poor sanitation practices. The 1952 Polio epidemic was the worst outbreak in the nation's history. Of nearly 58,000 cases reported that year, 3,145 people died and 21,269 were left with mild to disabling paralysis, with most of the victims being children. The "public reaction was to a plague", said historian William O'Neill. "Citizens of urban areas were to be terrified every summer when this frightful visitor returned.” A Polio vaccine first became available in 1955. 2. What are the symptoms of Polio? - Up to 95 % of people infected with Polio virus are not aware they are infected, but can still transmit it to others. While some develop just a fever, sore throat, upset stomach, and/or flu-like symptoms and have no paralysis or other serious symptoms, others get a stiffness of the back or legs, and experience increased sensitivity. However, a few develop life-threatening paralysis of muscles. The risk of developing serious symptoms increases with the age of the ill person. 3. Is Polio still a disease seen in the United States? - The last naturally occurring cases of Polio in the United States were in 1979, when an outbreak occurred among the Amish in several states including Pennsylvania. 4. What kinds of Polio vaccines are used in the United States? - There is now only one kind of Polio vaccine used in the United States: the Inactivated Polio vaccine (IPV) is given as an injection (shot). -

Interim Results for the Period Ended 30 June 2018

INTERIM RESULTS FOR THE PERIOD ENDED 30 JUNE 2018 Highlights • Golar LNG Partners LP (“Golar Partners” or “the Partnership”) reports net income attributable to unit holders of $28.4 million and operating income of $36.6 million for the second quarter of 2018. • Generated distributable cash flow1 of $23.0 million for the second quarter with a distribution coverage ratio1 of 0.56. • FLNG Hilli Episeyo accepted by charterers Perenco and SNH. Subsequent Events • Completed acquisition of initial equity interest in Golar Hilli LLC on July 12, 2018 and resume discussions on the potential acquisition of an additional equity interest. • Shipping market shows solid signs of improvement. Secured 10-month charter for Golar Maria. • Selected FSRU Golar Freeze to service 15-year Atlantic project. Vessel enters Dubai Drydocks. • Declared an unchanged distribution for the second quarter of $0.5775 per unit. Financial Results Overview Golar Partners reports net income attributable to unit holders of $28.4 million and operating income of $36.6 million for the second quarter of 2018 (“the second quarter” or “2Q”), as compared to net income attributable to unit holders of $14.8 million and operating income of $26.1 million for the first quarter of 2018 (“the first quarter” or “1Q”) and net income attributable to unit holders of $53.8 million and operating income of $87.4 million for 2Q 2017. 1 Refer to section 'Non-GAAP measures' for definition. (USD '000) Q2 2018 Q1 2018 Q2 2017 Total Operating Revenues 84,201 74,214 135,969 Adjusted EBITDA 1 61,805 51,715 113,539 Operating Income 36,640 26,066 87,397 Other Non-operating Income 236 — — Interest Income 3,300 3,482 1,447 Interest Expense (19,303 ) (20,314 ) (18,856 ) Other Financial Items, net 12,775 9,591 (7,710 ) Tax (4,503 ) (3,923 ) (4,652 ) Net Income attributable to Golar LNG Partners LP Owners 28,440 14,755 53,828 Net Debt 1 1,098,771 1,084,532 1,139,253 As anticipated, total operating revenues increased, from $74.2 million in 1Q to $84.2 million in 2Q.