SPD-Left Party/PDS Coalitions in the Eastern German Länder

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parlamentsmaterialien Beim DIP (PDF, 38KB

DIP21 Extrakt Deutscher Bundestag Diese Seite ist ein Auszug aus DIP, dem Dokumentations- und Informationssystem für Parlamentarische Vorgänge , das vom Deutschen Bundestag und vom Bundesrat gemeinsam betrieben wird. Mit DIP können Sie umfassende Recherchen zu den parlamentarischen Beratungen in beiden Häusern durchführen (ggf. oben klicken). Basisinformationen über den Vorgang [ID: 17-47093] 17. Wahlperiode Vorgangstyp: Gesetzgebung ... Gesetz zur Änderung des Urheberrechtsgesetzes Initiative: Bundesregierung Aktueller Stand: Verkündet Archivsignatur: XVII/424 GESTA-Ordnungsnummer: C132 Zustimmungsbedürftigkeit: Nein , laut Gesetzentwurf (Drs 514/12) Nein , laut Verkündung (BGBl I) Wichtige Drucksachen: BR-Drs 514/12 (Gesetzentwurf) BT-Drs 17/11470 (Gesetzentwurf) BT-Drs 17/12534 (Beschlussempfehlung und Bericht) Plenum: 1. Durchgang: BR-PlPr 901 , S. 448B - 448C 1. Beratung: BT-PlPr 17/211 , S. 25799A - 25809C 2. Beratung: BT-PlPr 17/226 , S. 28222B - 28237C 3. Beratung: BT-PlPr 17/226 , S. 28237B 2. Durchgang: BR-PlPr 908 , S. 160C - 160D Verkündung: Gesetz vom 07.05.2013 - Bundesgesetzblatt Teil I 2013 Nr. 23 14.05.2013 S. 1161 Titel bei Verkündung: Achtes Gesetz zur Änderung des Urheberrechtsgesetzes Inkrafttreten: 01.08.2013 Sachgebiete: Recht ; Medien, Kommunikation und Informationstechnik Inhalt Einführung eines sog. Leistungsschutzrechtes für Presseverlage zur Verbesserung des Schutzes von Presseerzeugnissen im Internet: ausschließliches Recht zur gewerblichen öffentlichen Zugänglichmachung als Schutz vor Suchmaschinen und vergleichbaren -

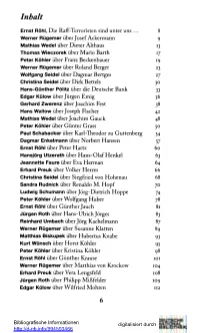

Inhalt Ernst Röhl, Die Raff-Terroristen Sind Unter Uns

Inhalt Ernst Röhl, Die Raff-Terroristen sind unter uns ... 8 Werner Rügemer über Josef Ackermann 9 Mathias Wedel über Dieter Althaus 13 Thomas Wieczorek über Mario Barth 17 Peter Köhler über Franz Beckenbauer 19 Werner Rügemer über Roland Berger 23 Wolfgang Seidel über Dagmar Bertges 27 Christina Seidel über Dirk Bettels 30 Hans-Günther Pölitz über die Deutsche Bank 33 Edgar Külow über Jürgen Emig 36 Gerhard Zwerenz über Joachim Fest 38 Hans Wallow über Joseph Fischer 42 Mathias Wedel über Joachim Gauck 48 Peter Köhler über Günter Grass 50 Paul Schabacker über Karl-Theodor zu Guttenberg 54 Dagmar Enkelmann über Norbert Hansen 57 Ernst Röhl über Peter Hartz 60 Hansjörg Utzerath über Hans-Olaf Henkel 63 Jeannette Faure über Eva Herman 64 Erhard Preuk über Volker Herres 66 Christina Seidel über Siegfried von Hohenau 68 Sandra Rudnick über Renaldo M. Hopf 70 Ludwig Schumann über Jörg-Dietrich Hoppe 74 Peter Köhler über Wolfgang Huber 78 Ernst Röhl über Günther Jauch 81 Jürgen Roth über Hans-Ulrich Jorges 83 Reinhard Limbach über Jörg Kachelmann 87 Werner Rügemer über Susanne Klatten 89 Matthias Biskupek über Hubertus Knabe 93 Kurt Wünsch über Horst Köhler 95 Peter Köhler über Kristina Köhler 98 Ernst Röhl über Günther Krause 101 Werner Rügemer über Matthias von Krockow 104 Erhard Preuk über Vera Lengsfeld 108 Jürgen Roth über Philipp Mißfelder 109 Edgar Külow über Wilfried Mohren 112 Bibliografische Informationen digitalisiert durch http://d-nb.info/994503466 Paul Schabacker über Franz Müntefering 115 Christoph Hofrichter über Günther Oettinger 120 Reinhard Limbach über Hubertus Pellengahr 122 Stephan Krull über Ferdinand Piëch 123 Ernst Röhl über Heinrich von Pierer 127 Paul Schabacker über Papst Benedikt XVI. -

Saurer Apfel

Deutschland Länder. Parteichef Oskar La- fontaine habe „ganz deutli- che Worte gesprochen“, rühmt Ringstorff, „wir ent- scheiden hier, wie die Re- gierung gebildet wird“. Was für die Mecklenburg- Vorpommerschen Sozialde- mokraten das Beste ist, da sind sich Spitzengenossen vor Ort einig – ein echtes Bündnis mit der PDS. Nur so seien die Postkommuni- sten zu disziplinieren. Das Wahlergebnis zwinge die SPD, sagt der Noch-Bundes- tagsabgeordnete Tilo Brau- ne aus Greifswald, „in den K. B. KARWASZ sauren Apfel der rot-roten Sozialdemokrat Ringstorff (r.), PDS-Landeschef Holter (hinten M.)*: „Größere Nähe“ Koalition zu beißen“. Und selbst Justizminister Rolf Eg- die sich erst einmal in der Opposition re- gert, Intimfeind der PDS, hat eingelenkt. MECKLENBURG-VORPOMMERN generiert. Eggert schwächte seine Drohung ab, er ste- Daß Ringstorff die Union überhaupt he für ein SPD-PDS-Kabinett nicht zur Ver- Saurer Apfel zum – unverbindlichen – Plausch lud, und fügung: „Das müßte ich mir überlegen.“ zwar noch vor der PDS, war ein geschick- Eine wichtige Rolle dürfte bei den Ver- Die SPD in Schwerin ter Zug: So erhöht er den Druck auf die handlungen der beiden Wahlsieger spie- Postkommunisten, die unbedingt mit an len, wen die PDS als ministrabel präsen- ist offiziell nach allen Seiten die Macht wollen, ihre Forderungen im tiert. Ihren Chef Holter, 45, etwa hält verhandlungsbereit. Doch vornhinein zu mäßigen. Dieselbe Strate- Ringstorff für einen „lupenreinen Sozial- die Signale stehen auf Rot-Rot. gie hat der clevere SPD-Mann schon vor demokraten“. Der frühere FDJler Andreas vier Jahren mit umgekehrten Vorzeichen Bluhm, 38, für das Amt des Kultusmini- as eierst du so rum“, raunzte der erfolgreich angewandt, um den Preis für sters im Gespräch, tritt heute so jovial auf Vorsitzende der Gewerkschaft eine Große Koalition hochzutreiben. -

Entscheidung Im „Kreml“ Tung Der Lebensrealität Im Abgewickelten Arbeiter-Und-Bauern-Staat

teressen des Ostens bezeichnen darf. Der Streit in der SPD ist Teil eines Kultur- kampfes, der Ostdeutschland spaltet. Denn auch die Konservativen haben ihre Probleme mit der unterschiedlichen Deu- Entscheidung im „Kreml“ tung der Lebensrealität im abgewickelten Arbeiter-und-Bauern-Staat. Wenn Bürger- Sozialdemokraten aus Ost und West streiten darüber, ob die rechtler Arnold Vaatz und der letzte DDR- Autorin Daniela Dahn als Verfassungshüterin taugt. Ministerpräsident Lothar de Maizière um die Aufnahme früherer SED-Mitglieder elten besaß die Kulisse einer Aus- Dabei hatte Ex-Pfarrer Kuhnert einst streiten oder Joachim Gauck, der Herr einandersetzung soviel Symbol- ein gutes Verhältnis zu Dahn. 1988 lud über die Stasi-Akten, und Alt-Bundesprä- Skraft wie in diesem Fall. Noch er sie sogar in seine Kirche zur Lesung sident Richard von Weizsäcker vornehm, heute nennen die Potsdamer das Haus, ein. Dahn war zwar SED-Mitglied, doch aber nicht weniger entschlossen über den in dem einst die SED-Bezirksleitung weil sie in ihrer „Prenzlauer Berg- Umgang mit der DDR-Geschichte debat- residierte, den „Kreml“; noch immer Tour“ den Realsozialismus halbwegs tieren, werden die unterschiedlichen Be- sind am Turm die Umrisse des Sym- real beschrieben hatte, galt sie als kri- trachtungsweisen ebenso deutlich wie bei bols der SED zu erkennen. Drinnen hat tischer Geist. Zehn Jahre später stehen den Diskussionen in der SPD. inzwischen die Demokratie Einzug ge- beide sich nun im „Kreml“ gegenüber Doch die Christdemokraten können aus halten – im „Kreml“ tagt der branden- – als politische Gegner. sicherer Distanz leicht streiten. Die SPD burgische Landtag. Die Front der Auseinandersetzung dagegen leidet sichtlich unter den alltägli- Welche Macht der alte Geist des verläuft allerdings auch quer durch die chen Auseinandersetzungen mit den Post- Hauses noch haben darf, darüber wird SPD. -

The Rise of Syriza: an Interview with Aristides Baltas

THE RISE OF SYRIZA: AN INTERVIEW WITH ARISTIDES BALTAS This interview with Aristides Baltas, the eminent Greek philosopher who was one of the founders of Syriza and is currently a coordinator of its policy planning committee, was conducted by Leo Panitch with the help of Michalis Spourdalakis in Athens on 29 May 2012, three weeks after Syriza came a close second in the first Greek election of 6 May, and just three days before the party’s platform was to be revealed for the second election of 17 June. Leo Panitch (LP): Can we begin with the question of what is distinctive about Syriza in terms of socialist strategy today? Aristides Baltas (AB): I think that independently of everything else, what’s happening in Greece does have a bearing on socialist strategy, which is not possible to discuss during the electoral campaign, but which will present issues that we’re going to face after the elections, no matter how the elections turn out. We haven’t had the opportunity to discuss this, because we are doing so many diverse things that we look like a chicken running around with its head cut off. But this is precisely why I first want to step back to 2008, when through an interesting procedure, Synaspismos, the main party in the Syriza coalition, formulated the main elements of the programme in a book of over 300 pages. The polls were showing that Syriza was growing in popularity (indeed we reached over 15 per cent in voting intentions that year), and there was a big pressure on us at that time, as we kept hearing: ‘you don’t have a programme; we don’t know who you are; we don’t know what you’re saying’. -

ROSA LUXEMBURG STIFTUNG Frauen Macht Politik Politikerinnen

frauen macht ROSA LUXEMBURG STIFTUNG politik ARCHIV DEMOKRATISCHER SOZIALISMUS AUSSTELLUNG «FRAUEN MACHT POLITIK» Diese Ausstellung zeigt die Überlieferung ausgewählter linker Politikerinnen, die für die PDS bzw. DIE LINKE an prominenter Stelle als Abgeordnete im Deutschen Bun- destag tätig waren und sind. Dargestellt werden soll, in welchem Umfang sie vor dem Hintergrund ihrer politi- schen Biografien angemessen im Archiv repräsentiert sind. Diese aktuelle Ausstellung basiert auf einer älteren Fassung vom März 2014 zum Tag der Archive, der unter dem Motto «Frauen – Männer – Macht» stand. Auf Grundla- ge thematischer Archivrecherchen sind damals Ausstellungstafeln zur Dokumen- tation der Aktivitäten der PDS-Bundestagsfraktion/-gruppe zu feministischen und familienpolitischen Themen, Gender- und Geschlechterpolitik (1990–2002) entstan- den. Zudem wurden aus den erschlossenen Personenbeständen des Archivs Politi- kerinnen ausgewählt, die sich in den 90er Jahren in der PDS engagierten und spä- ter als Abgeordnete im Bundestag ihre Positionen vertraten. Hierfür stehen Petra Bläss, Dagmar Enkelmann, Heidi Knake-Werner, Gesine Lötzsch, Christa Luft und Rosel Neuhäuser. Aktuell neu entstanden ist die Tafel zu Ulla Jelpke. Die Vielfalt des präsentierten Archiv- und Sammlungsgutes soll die aus heutiger Perspektive schon historischen gesellschaftspolitischen Debatten der Umbruchs- zeit in der Bundesrepublik der 90er Jahre vergegenwärtigen. Der auch als Aufforderung zu verstehende Titel «frauen macht politik» ist und bleibt die Voraussetzung für -

Deutscher Bundestag

Deutscher Bundestag 54. Sitzung des Deutschen Bundestages am Donnerstag, 25.September 2014 Endgültiges Ergebnis der Namentlichen Abstimmung Nr. 2 Entschließungsantrag der Abgeordneten Klaus Ernst, Matthias W. Birkwald, Susanna Karawanskij, weiterer Abgeordneter und der Fraktion DIE LINKE. zu der Beratung der Antwort der Bundesregierung auf die Große Anfrage der Abgeordneten Klaus Ernst, Thomas Nord, Herbert Behrens, weiterer Abgeordneter und der Fraktion DIE LINKE. Soziale, ökologische, ökonomische und poltitische Effekte des EU-USA Freihandelsabkommens Drs. 18/432, 1872100 und 18/2611 Abgegebene Stimmen insgesamt: 578 Nicht abgegebene Stimmen: 53 Ja-Stimmen: 112 Nein-Stimmen: 460 Enthaltungen: 6 Ungültige: 0 Berlin, den 25.09.2014 Beginn: 13:09 Ende: 13:12 Seite: 1 Seite: 2 Seite: 2 CDU/CSU Name Ja Nein Enthaltung Ungült. Nicht abg. Stephan Albani X Katrin Albsteiger X Peter Altmaier X Artur Auernhammer X Dorothee Bär X Thomas Bareiß X Norbert Barthle X Julia Bartz X Günter Baumann X Maik Beermann X Manfred Behrens (Börde) X Veronika Bellmann X Sybille Benning X Dr. Andre Berghegger X Dr. Christoph Bergner X Ute Bertram X Peter Beyer X Steffen Bilger X Clemens Binninger X Peter Bleser X Dr. Maria Böhmer X Wolfgang Bosbach X Norbert Brackmann X Klaus Brähmig X Michael Brand X Dr. Reinhard Brandl X Helmut Brandt X Dr. Ralf Brauksiepe X Dr. Helge Braun X Heike Brehmer X Ralph Brinkhaus X Cajus Caesar X Gitta Connemann X Alexandra Dinges-Dierig X Alexander Dobrindt X Michael Donth X Thomas Dörflinger X Marie-Luise Dött X Hansjörg Durz X Jutta Eckenbach X Dr. Bernd Fabritius X Hermann Färber X Uwe Feiler X Dr. -

In Einem Antrag Fordern Wir Die Bundesregierung Dazu Auf, Das

Deutscher Bundestag Drucksache 19/… 19. Wahlperiode Datum] Antrag der Abgeordneten Sevim Dagdelen, Heike Hänsel, Michel Brandt, Christine Buchholz, Dr. Diether Dehm, Dr. Gregor Gysi, Matthias Höhn, Andrej Hunko, Zaklin Nastic, Dr. Alexander S. Neu, Thomas Nord, Tobias Pflüger, Eva-Maria Schreiber, Helin Evrim Sommer, Alexander Ulrich, Kathrin Vogler und der Fraktion DIE LINKE. Verbotsverfahren gegen Oppositionspartei HDP klar verurteilen Der Bundestag wolle beschließen: I. Der Deutsche Bundestag stellt fest: 1. Der Deutsche Bundestag ist besorgt über die Massenverhaftungen von Politikerinnen und Politikern der Demokratischen Partei der Völker (HDP) in der Türkei. Das von der türkischen Generalstaatsanwaltschaft am 17. März 2021 beim Verfassungsgericht beantragte Verbot der zweitgrößten Oppositionspartei in dem NATO-Mitgliedsland unter Verweis auf absurde und konstruierte Terrorvorwürfe ist ein Anschlag auf alle Demokratinnen und Demokraten. Die HDP hat bei den Parlamentswahlen im Jahr 2018 fast sechs Millionen Wählerstimmen erhalten. 2. Der Deutsche Bundestag stellt fest, dass ein Verbot der HDP einem Putschversuch in der Türkei mit dem Ziel gleichkommt, der Koalition der Volksallianz von Staatspräsident Erdogan aus AKP und MHP bei aller weiteren Wahlen eine Mehrheit unabhängig vom Wählerwillen zu verschaffen. 3. Der Deutsche Bundestag stellt fest, dass insbesondere seit dem Jahr 2016 Regierungsgegner und Kritiker des türkischen Präsidenten Recep Tayyip Erdoğan massenweise verfolgt, darunter unzählige Journalistinnen und Journalisten -

Vorstände Der Parlamentariergruppen in Der 18. Wahlperiode

1 Vorstände der Parlamentariergruppen in der 18. Wahlperiode Deutsch-Ägyptische Parlamentariergruppe Vorsitz: Karin Maag (CDU/CSU) stv. Vors.: Dr. h.c. Edelgard Bulmahn (SPD) stv. Vors.: Heike Hänsel (DIE LINKE.) stv. Vors.: Dr. Franziska Brantner (BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN) Parlamentariergruppe Arabischsprachige Staaten des Nahen Ostens (Bahrain, Irak, Jemen, Jordanien, Katar, Kuwait, Libanon, Oman, Saudi Arabien, Syrien, Vereinigte Arabische Emirate, Arbeitsgruppe Palästina) Vorsitz: Michael Hennrich (CDU/CSU) stv. Vors.: Gabriele Groneberg (SPD) stv. Vors.: Heidrun Bluhm (DIE LINKE.) stv. Vors.: Luise Amtsberg (BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN) Parlamentariergruppe ASEAN (Brunei, Indonesien, Kambodscha, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippinen, Singapur, Thailand, Vietnam) Vorsitz: Dr. Thomas Gambke (BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN) stv. Vors.: Dr. Michael Fuchs (CDU/CSU) stv. Vors.: Johann Saathoff (SPD) stv. Vors.: Caren Lay (DIE LINKE.) Deutsch-Australisch-Neuseeländische Parlamentariergruppe (Australien, Neuseeland, Ost-Timor) Vorsitz: Volkmar Klein(CDU/CSU) stv. Vors.: Rainer Spiering (SPD) stv. Vors.: Cornelia Möhring (DIE LINKE.) stv. Vors.: Anja Hajduk (BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN) Deutsch-Baltische Parlamentariergruppe (Estland, Lettland, Litauen) Vorsitz: Alois Karl (CDU/CSU) stv. Vors.: René Röspel (SPD) stv. Vors.: Dr. Axel Troost (DIE LINKE.) stv. Vors.: Dr. Konstantin von Notz (BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN) Deutsch-Belarussische Parlamentariergruppe Vorsitz: Oliver Kaczmarek (SPD) stv. Vors.: Dr. Johann Wadephul (CDU/CSU) stv. Vors.: Andrej Hunko (DIE LINKE.) stv. Vors.: N.N. (BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN) 2 Deutsch-Belgisch-Luxemburgische Parlamentariergruppe (Belgien, Luxemburg) Vorsitz: Patrick Schnieder (CDU/CSU) stv. Vors.: Dr. Daniela de Ridder (SPD) stv. Vors.: Katrin Werner (DIE LINKE.) stv. Vors.: Corinna Rüffer (BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN) Parlamentariergruppe Bosnien und Herzegowina Vorsitz: Marieluise Beck (BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN) stv. -

DHB Kapitel 4.2 Wahl Und Amtszeit Der Vizepräsidenten Des Deutschen 13.08.2021 Bundestages

DHB Kapitel 4.2 Wahl und Amtszeit der Vizepräsidenten des Deutschen 13.08.2021 Bundestages 4.2 Wahl und Amtszeit der Vizepräsidenten des Deutschen Bundestages Stand: 13.8.2021 Grundlagen und Besonderheiten bei den Wahlen der Vizepräsidenten Die Stellvertreter des Präsidenten werden wie der Bundestagspräsident für die Dauer der Wahlperiode gewählt und können nicht abgewählt werden. Für die Wahl der Stellvertreter des Präsidenten sieht die Geschäftsordnung des Bundestages in § 2 Absatz 1 und 2 getrennte Wahlhandlungen mit verdeckten Stimmzetteln vor. In der 12. Wahlperiode (1990) sowie in der 17., 18. und 19. Wahlperiode (2009, 2013 und 2017) wurden die Stellvertreter mit verdeckten Stimmzetteln in einem Wahlgang (also mit einer Stimmkarte) gewählt1. In der 13. Wahlperiode (1994) wurde BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN drittstärkste Fraktion und beanspruchte einen Platz im Präsidium. Die SPD wollte andererseits auf einen ihrer bisherigen zwei Vizepräsidenten nicht verzichten. Zugleich war erkennbar, dass sich keine Mehrheit für eine Vergrößerung des Präsidiums von fünf auf sechs Mitglieder finden ließ, und die FDP war nicht bereit, als nunmehr kleinste Fraktion aus dem Präsidium auszuscheiden. Da eine interfraktionelle Einigung nicht zustande kam, musste die Wahl der Vizepräsidenten mit Hilfe einer Geschäftsordnungsänderung durchgeführt werden. Vor der eigentlichen Wahl kam es nach einer längeren Geschäftsordnungsdebatte zu folgendem Verfahren2: 1. Abstimmung über den Änderungsantrag der Fraktion BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN: Einräumung eines Grundmandats im Präsidium für jede Fraktion (Drucksache 13/8): Annahme. 2. Abstimmung über den Änderungsantrag der Fraktion der SPD: Erweiterung des Präsidiums auf sechs Mitglieder (Drucksache 13/7): Ablehnung. 3. Abstimmung über den Änderungsantrag der Gruppe der PDS: Einräumung eines Grundmandats im Präsidium für jede Fraktion und Gruppe (Drucksache 13/15 [neu]): Ablehnung. -

Germany's Left Party Is Shut out of Government, but Remains a Powerful

Germany’s Left Party is shut out of government, but remains a powerful player in German politics blogs.lse.ac.uk/europpblog/2013/09/19/germanys-left-party-is-shut-out-of-government-but-remains-a-powerful- player-in-german-politics/ 19/09/2013 The Left Party (Die Linke) received 11.9 per cent of the vote in the 2009 German federal elections, and is predicted to comfortably clear the country’s 5 per cent threshold in this Sunday’s vote. Jonathan Olsen outlines the party’s recent history and its role in the German party system. He notes that although the Left Party appears willing to enter into coalition with the other major parties, it is not viewed as a viable coalition partner. Despite being shut out of government, the party nevertheless remains an important part of German politics. Although the government that emerges after Germany’s federal elections on 22 September will largely depend on the performance of the two biggest parties, the conservative block of CDU/CSU and the Left-Center Social Democrats (SPD), the impact of smaller parties on the ultimate outcome should not be underestimated. Thus the failure of the Free Democrats (FDP) to clear the 5 per cent hurdle necessary for legislative representation would most likely lead to a “Grand Coalition” of CDU/CSU and SPD, while an outstanding performance by the German Greens could make possible (though unlikely) an SPD-Greens coalition government. The third of Germany’s smaller parties – the Left Party – will not have the same impact on coalition calculations as the FDP and Greens, since all of the other four parties have categorically ruled out a coalition with it. -

The Making of SYRIZA

Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism On-Line Panos Petrou The making of SYRIZA Published: June 11, 2012. http://socialistworker.org/print/2012/06/11/the-making-of-syriza Transcription, Editing and Markup: Sam Richards and Paul Saba Copyright: This work is in the Public Domain under the Creative Commons Common Deed. You can freely copy, distribute and display this work; as well as make derivative and commercial works. Please credit the Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism On-Line as your source, include the url to this work, and note any of the transcribers, editors & proofreaders above. June 11, 2012 -- Socialist Worker (USA) -- Greece's Coalition of the Radical Left, SYRIZA, has a chance of winning parliamentary elections in Greece on June 17, which would give it an opportunity to form a government of the left that would reject the drastic austerity measures imposed on Greece as a condition of the European Union's bailout of the country's financial elite. SYRIZA rose from small-party status to a second-place finish in elections on May 6, 2012, finishing ahead of the PASOK party, which has ruled Greece for most of the past four decades, and close behind the main conservative party New Democracy. When none of the three top finishers were able to form a government with a majority in parliament, a date for a new election was set -- and SYRIZA has been neck-and-neck with New Democracy ever since. Where did SYRIZA, an alliance of numerous left-wing organisations and unaffiliated individuals, come from? Panos Petrou, a leading member of Internationalist Workers Left (DEA, by its initials in Greek), a revolutionary socialist organisation that co-founded SYRIZA in 2004, explains how the coalition rose to the prominence it has today.