2020 Torit County Multi-Sector Household Survey Full Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019 Torit Multi-Sector Household Survey Report

2019 Torit Multi-Sector Household Survey Report February 2019 Contents RECENT OVERALL TRENDS and BASIC RECOMMENDATIONS ..................................................................... 4 BACKGROUND ............................................................................................................................................. 6 TORIT DASHBOARD ..................................................................................................................................... 7 COMMUNITY CONSOLE ............................................................................................................................ 10 I. PURPOSE, METHODOLOGY and SCOPE ............................................................................................. 11 PEOPLE WELFARE ...................................................................................................................................... 15 1. LIVELIHOOD ....................................................................................................................................... 15 2. MAIN PROBLEMS and RESILIENCE (COPING CAPACITY) ................................................................... 17 3. FOOD SECURITY................................................................................................................................. 19 4. HEALTH .............................................................................................................................................. 22 5. HYGIENE ........................................................................................................................................... -

Magwi County

Resettlement, Resource Conflicts, Livelihood Revival and Reintegration in South Sudan A study of the processes and institutional issues at the local level in Magwi County by N. Shanmugaratnam Noragric Department of International Environment and Development No. Report Noragric Studies 5 8 RESETTLEMENT, RESOURCE CONFLICTS, LIVELIHOOD REVIVAL AND REINTEGRATION IN SOUTH SUDAN A study of the processes and institutional issues at the local level in Magwi County By N. Shanmugaratnam Noragric Report No. 58 December 2010 Department of International Environment and Development Studies, Noragric Norwegian University of Life Sciences, UMB Noragric is the Department of International Environment and Development Studies at the Norwegian University of Life Sciences (UMB). Noragric’s activities include research, education and assignments, focusing particularly, but not exclusively, on developing countries and countries with economies in transition. Noragric Reports present findings from various studies and assignments, including programme appraisals and evaluations. This Noragric Report was commissioned by the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (Norad) under the framework agreement with UMB which is administrated by Noragric. Extracts from this publication may only be reproduced after prior consultation with the employer of the assignment (Norad) and with the consultant team leader (Noragric). The findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed in this publication are entirely those of the authors and cannot be attributed directly to the Department of International Environment and Development Studies (UMB/Noragric). Shanmugaratnam, N. Resettlement, resource conflicts, livelihood revival and reintegration in South Sudan: A study of the processes and institutional issues at the local level in Magwi County. Noragric Report No. 58 (December 2010) Department of International Environment and Development Studies, Noragric Norwegian University of Life Sciences (UMB) P.O. -

Crossing Lines: “Magnets” and Mobility Among Southern Sudanese

“Magnets” andMobilityamongSouthernSudanese Crossing Lines United States Agency for InternationalDevelopment Agency for United States Contract No. HNE-I-00-00-00038-00 BEPS Basic Education and Policy Support (BEPS) Activity CREATIVE ASSOCIATES INTERNATIONAL INC In collaboration with CARE, THE GEORGE WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY, AND GROUNDWORK Crossing Lines “Magnets” and Mobility among Southern Sudanese A final report of two assessment trips examining the impact and broader implications of a new teacher training center in the Kakuma refugee camps, Kenya Prepared by: Marc Sommers Youth at Risk Specialist, CARE Basic Education and Policy Support Activity (BEPS) CARE, Inc. 151 Ellis Street, NE Atlanta, GA 30303-2439 and Creative Associates International, Inc. 5301 Wisconsin Avenue, NW Suite 700 Washington, DC 20015 Prepared for: Basic Education and Policy Support (BEPS) Activity US Agency for International Development Contract No. HNE-I-00-00-00038-00 Creative Associates International, Inc., Prime Contractor Photo credit: Marc Sommers 2002 Crossing Lines: “Magnets” and Mobility among Southern Sudanese CONTENTS I. Introduction: Do Education Facilities Attract Displaced People? The Current Debate .........................................................................................................................1 II. Background: Why Study Teacher Training in Kakuma and Southern Sudan? ......... 3 III. Findings: Issues Related to Mobility in Southern Sudan........................................... 8 A. Institutions at Odds: Contrasting Perceptions........................................................ -

Uganda Fighting for Decades

Southern Torit County Displacement and Service Access Brief Torit County, Eastern Equatoria State, South Sudan, November 2017 Background Map 1: Displacement in southern Torit County Major Town In response to reports of persistent needs and a growing population From Juba of Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) in the mountain and valley Assessed Village areas of southern Torit County, REACH joined a Rapid Response Mission team constituted by the World Food Program (WFP) and the Torit United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) in Gunyoro village, Ifwotu Payam. A concurrent screening and distribution took place in Iholong village, also in Ifwotu Payam, but was cut short due to nearby fighting. Gunyoro The assessment was conducted from 17-20 November and consisted of 4 KI interviews with community leaders, 2 gender-disaggregated Iholong Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) with a total of 28 participants, continuous interaction with community members during aid provision, Magwi and general observation of the area by foot and helicopter. Findings should be considered as indicative only, and further verification via site visits should occur where possible. Population Movement and Displacement Torit and the foothills of the Imatong Mountains to its south have seen To Uganda fighting for decades. In the last few years, the population in the area via Nimule has been in flux, with frequent displacement inflows and outflows, and nearly continuous internal movements. Imatong Mountains Displacement into southern Torit County Road Displacement to southern Torit County has been occurring Displacement to the area continuously since 2013, with two large waves following conflict in the Displacement within the area last few years. -

Review of Rinderpest Control in Southern Sudan 1989-2000

Review of Rinderpest Control in Southern Sudan 1989-2000 Prepared for the Community-based Animal Health and Epidemiology (CAPE) Unit of the Pan African Programme for the Control of Epizootics (PACE) Bryony Jones March 2001 Acknowledgements The information contained in this document has been collected over the years by southern Sudanese animal health workers, UNICEF/OLS Livestock Project staff, Tufts University consultants, and the staff of NGOs that have supported community-based animal health projects in southern Sudan (ACROSS, ACORD, ADRA, DOT, GAA, NPA, Oxfam-GB, Oxfam-Quebec, SC-UK, VETAID, VSF-B, VSF-CH, VSF-G, Vetwork Services Trust, World Relief). The individuals involved are too numerous to name, but their hard work and contribution of information is gratefully acknowledged. The data from the early years of the OLS Livestock Programme (1993 to 1996) was collated by Tim Leyland, formerly UNICEF/OLS Livestock Project Officer. Disease outbreak information from 1998 to date has been collated by Dr Gachengo Matindi, FAO/OLS Livestock Officer (formerly UNICEF/OLS Livestock Officer). Rinderpest serology and virus testing has mainly been carried out by National Veterinary Research Centre, Muguga, Nairobi. Any errors or omissions in this review are the fault of the author. If any reader has additional information to correct an error or omission the author would be grateful to receive this information. For further information contact: CAPE Unit PACE Programme OAU/IBAR PO Box 30786 Nairobi Tel: Nairobi 226447 Fax: Nairobi 226565 E mail: [email protected] Or the author: Bryony Jones PO Box 13434 Nairobi Kenya Tel: Nairobi 580799 E mail: [email protected] 2 CONTENTS Page 1. -

Symptoms and Causes: Insecurity and Underdevelopment in Eastern

sudanHuman Security Baseline Assessment issue brief Small Arms Survey Number 16 April 2010 Symptoms and causes Insecurity and underdevelopment in Eastern Equatoria astern Equatoria state (EES) is The survey was supplemented by qual- 24,789 (± 965) households in the one of the most volatile and itative interviews and focus group three counties contain at least one E conflict-prone states in South- discussions with key stakeholders in firearm. ern Sudan. An epicentre of the civil EES and Juba in January 2010. Respondents cited traditional lead- war (1983–2005), EES saw intense Key findings include: ers (clan elders and village chiefs) fighting between the Sudanese Armed as the primary security providers Across the entire sample, respond- Forces (SAF) and the Sudan People’s in their areas (90 per cent), followed ents ranked education and access Liberation Army (SPLA), as well by neighbours (48 per cent) and reli- to adequate health care as their numerous armed groups supported gious leaders (38 per cent). Police most pressing concerns, followed by both sides, leaving behind a legacy presence was only cited by 27 per by clean water. Food was also a top of landmines and unexploded ordnance, cent of respondents and the SPLA concern in Torit and Ikotos. Security high numbers of weapons in civilian by even fewer (6 per cent). ranked at or near the bottom of hands, and shattered social and com- Attitudes towards disarmament overall concerns in all counties. munity relations. were positive, with around 68 per When asked about their greatest EES has also experienced chronic cent of the total sample reporting a security concerns, respondents in food insecurity, a lack of basic services, willingness to give up their firearms, Torit and Ikotos cited cattle rustling, and few economic opportunities. -

Operational Deployment Plan Template

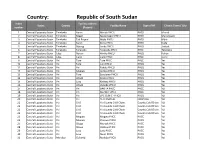

Country: Republic of South Sudan Index Facility Address States County Facility Name Type of HF Closest Town / City number (Payam) 1 Central Equatoria State Terekeka Nyori Moridi PHCU PHCU Moridi 2 Central Equatoria State Terekeka Reggo Makamagor PHCU PHCU Makamagor 3 Central Equatoria State Terekeka Tali Payam Mijiki PHCU PHCU Mijiki 4 Central Equatoria State Terekeka Nyori Kuda PHCU PHCU Kuda 5 Central Equatoria State Terekeka Rijiong Jonko PHCU PHCU Jonkok 6 Central Equatoria State Terekeka Terekeka Terekeka PHCC PHCC Terekeka 7 Central Equatoria State Juba Rokon Miriko PHCU PHCU Rokon 8 Central Equatoria State Juba Ganji Ganji PHCC PHCC Ganji 9 Central Equatoria State Yei Tore Tore PHCC PHCC Yei 10 Central Equatoria State Yei Tore Goli PHCU PHCU Yei 11 Central Equatoria State Yei Yei Pakula PHCU PHCU Yei 12 Central Equatoria State Yei Mugwo Jombu PHCU PHCU Yei 13 Central Equatoria State Yei Tore Bandame PHCU PHCU Yei 14 Central Equatoria State Yei Otogo Kejiko PHCU PHCU Yei 15 Central Equatoria State Yei Lasu Kirikwa PHCU PHCU Yei 16 Central Equatoria State Yei Otogo Rubeke PHCU PHCU Yei 17 Central Equatoria State Yei Yei BAKITA PHCC PHCC YEI 18 Central Equatoria State Yei Yei Marther PHCC PHCC YEI 19 Central Equatoria State Yei Yei EPC CLINIC - PHCU PHCU YEI 20 Central Equatoria State Yei Yei YEI HOSPITAL HOSPITAL YEI 21 Central Equatoria State Yei CHD Yei County Cold Chain County Cold Chain YEI 22 Central Equatoria State Yei CHD Yei County Cold Chain County Cold Chain YEI 23 Central Equatoria State Yei CHD Yei County Cold Chain County -

South Sudan Country Operational Plan (COP)

FY 2015 South Sudan Country Operational Plan (COP) The following elements included in this document, in addition to “Budget and Target Reports” posted separately on www.PEPFAR.gov, reflect the approved FY 2015 COP for South Sudan. 1) FY 2015 COP Strategic Development Summary (SDS) narrative communicates the epidemiologic and country/regional context; methods used for programmatic design; findings of integrated data analysis; and strategic direction for the investments and programs. Note that PEPFAR summary targets discussed within the SDS were accurate as of COP approval and may have been adjusted as site- specific targets were finalized. See the “COP 15 Targets by Subnational Unit” sheets that follow for final approved targets. 2) COP 15 Targets by Subnational Unit includes approved COP 15 targets (targets to be achieved by September 30, 2016). As noted, these may differ from targets embedded within the SDS narrative document and reflect final approved targets. Approved FY 2015 COP budgets by mechanism and program area, and summary targets are posted as a separate document on www.PEPFAR.gov in the “FY 2015 Country Operational Plan Budget and Target Report.” South Sudan Country/Regional Operational Plan (COP/ROP) 2015 Strategic Direction Summary August 27, 2015 Table of Contents Goal Statement 1.0 Epidemic, Response, and Program Context 1.1 Summary statistics, disease burden and epidemic profile 1.2 Investment profile 1.3 Sustainability Profile 1.4 Alignment of PEPFAR investments geographically to burden of disease 1.5 Stakeholder engagement -

South Sudan Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) Report — Lakes State, Western and Eastern Equatoria

South Sudan water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) Report — Lakes State, Western and Eastern Equatoria January 2021 South Sudan WASH Report — Lakes State, Western and Eastern Equatoria Cover photo credit: Gatbel Chany, 2021 About REACH REACH facilitates the development of information tools and products that enhance the capacity of aid actors to make evidence-based decisions in emergency, recovery and development contexts. The methodologies used by REACH include primary data collection and in-depth analysis, and all activities are conducted through inter-agency aid coordination mechanisms. REACH is a joint initiative of IMPACT Initiatives, ACTED and the United Nations Institute for Training and Research - Operational Satellite Applications Programme (UNITAR-UNOSAT). For more information please visit our website: www.reach-initiative.org. You can contact us directly at: geneva@reach- initiative.org and follow us on Twitter @REACH_info. 1 South Sudan WASH Report — Lakes State, Western and Eastern Equatoria CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................................... 3 METHODOLOGY ......................................................................................................................................... 4 FINDINGS .................................................................................................................................................. 5 1. Access to water .................................................................................................................................... -

SOUTH SUDAN SITUATION REPORT 31 August 2018

UNICEF SOUTH SUDAN SITUATION REPORT 31 August 2018 South Sudan Humanitarian Situation Report 01 – 31 AUGUST 2018: SOUTH SUDAN SITREP #124 SITUATION IN NUMBERS Highlights 1.91 million • Since the signing of the peace agreement between the government and the Internally displaced persons (IDPs) opposition groups on 5 August in Khartoum, incidents of armed conflict have (OCHA South Sudan Humanitarian Snapshot, reduced significantly. However, the Ceasefire and Transitional Security 7 September 2018) Arrangements Monitoring Mechanism (CTSAMM) has accused government and SPLA-iO pro-Machar forces of violating the Permanent Ceasefire, following 2.47 million reported clashes in Unity and Bringi on 19 and 21 August, respectively. South Sudanese refugees in • Despite ongoing conflict in areas of Greater Upper Nile, Greater Equatoria and neighbouring countries (OCHA South Sudan Humanitarian Snapshot, Western Bahr el Ghazal, UNICEF was able to reopen and resume services at 10 7 September 2018) outpatient therapeutic programme (OTP) sites, including in Koch (4), Leer (2), Mayendit (2) and Rubkona (2). • World Breastfeeding Week was celebrated on 1-7 August, under the theme 7.1 million South Sudanese who are severely “Breastfeeding, Foundation of Life.” C4D implementing partners across the food insecure country supported the commemoration with activities such as radio messaging, (May-July 2018 Projection, Integrated Food public address systems and traditional dances to raise awareness on the Security Phase Classification) importance of breastfeeding -

Kapoeta Road Monitoring South Sudan Displacement Crisis Kapoeta, Eastern Equatoria State, South Sudan April 2020

Kapoeta Road Monitoring South Sudan Displacement Crisis Kapoeta, Eastern Equatoria State, South Sudan April 2020 CONTEXT AND METHODOLOGY Kapoeta town is located in Kapoeta South County, Eastern Equatoria State, near South Sudan ain movement leaving GENERAL CROSS BORDER MOVEMENT TRENDS apoeta Sudan’s border with Kenya. Since the beginning of the crisis in South Sudan in December Average daily number of individuals departing (red) and arriving (grey) with the intention to stay longer than six months, April 2019 to April 2020 Ethiopia ain movement arriving 2013, Kapoeta town has been a gateway through which many internally displaced persons in apoeta C.A.R. (IDPs) have passed on their way to refugee camps in Kenya. Lopa 15 et popation inos This factsheet provides results from the REACH road monitoring exercise in Kapoeta town. D.R.C. Kenya 12 et popation otos Uganda Kapoeta REACH monitors two bus/car parks where travellers are travelling to and from Torit/Juba and Kapoeta East 9 Narus/Kakuma, in order to record the arrivals and departures of households (HHs) on a daily Lafon North basis. The following findings are based on primary data collected over 24 days between 7 and apoeta Town Kapoeta South 6 30 April 2020. In April, 40 of surveyed HHs (110 individuals) were departures from Kapoeta Torom uba 3 town, 8 HHs (33 individuals) were arrivals to Kapoeta town and 6 HHs (9 individuals) were 0 transit. None of the arrivals or departures were cross-border movements, likely due to Torit Apr-19 May-19 Jun-19 Jul-19 Aug-19 Sep-19 Oct-19 Nov-19 Dec-19 Jan-20 Feb-20 March-20 April-20 COVID-19 related movement restrictions including the closure of national borders.9 Budi Kenya Therefore, while the PRM findings usually pertain to cross-border movements, this current INBOUND AND OUTBOUND MOVEMENT THROUGH KAPOETA round only presents data from internal movements arriving in or departing from Kapoeta town. -

2020 Magwi Multi-Sector Household Survey Report

2020 Magwi Multi-Sector Household Survey Report FINAL DRAFT to be validated through consultation and interview of local leaders April 2020 Contents FINDINGS and RECOMMENDATIONS .......................................................................................................... 4 DASHBOARD ................................................................................................................................................ 6 COMMUNITY CONSOLE .............................................................................................................................. 9 PURPOSE, METHODOLOGY and SCOPE .................................................................................................... 10 PEOPLE WELFARE ...................................................................................................................................... 14 1. LIVELIHOOD ....................................................................................................................................... 14 2. MAIN PROBLEMS and RESILIENCE (COPING CAPACITY) ................................................................... 17 3. FOOD SECURITY................................................................................................................................. 20 4. HEALTH .............................................................................................................................................. 23 5. HYGIENE ...........................................................................................................................................