Crossing Lines: “Magnets” and Mobility Among Southern Sudanese

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Criminalization of South Sudan's Gold Sector

The Criminalization of South Sudan’s Gold Sector Kleptocratic Networks and the Gold Trade in Kapoeta By the Enough Project April 2020* A Precious Resource in an Arid Land Within the area historically known as the state of Eastern Equatoria, Kapoeta is a semi-arid rangeland of clay soil dotted with short, thorny shrubs and other vegetation.1 Precious resources lie below this desolate landscape. Eastern Equatoria, along with the region historically known as Central Equatoria, contains some of the most important and best-known sites for artisanal and small-scale gold mining (ASM). Some estimates put the number of miners at 60,000 working at 80 different locations in the area, including Nanaknak, Lauro (Didinga Hills), Napotpot, and Namurnyang. Locals primarily use traditional mining techniques, panning for gold from seasonal streams in various villages. The work provides miners’ families resources to support their basic needs.2 Kapoeta’s increasingly coveted gold resources are being smuggled across the border into Kenya with the active complicity of local and national governments. This smuggling network, which involves international mining interests, has contributed to increased militarization.3 Armed actors and corrupt networks are fueling low-intensity conflicts over land, particularly over the ownership of mining sites, and causing the militarization of gold mining in the area. Poor oversight and conflicts over the control of resources between the Kapoeta government and the national government in Juba enrich opportunistic actors both inside and outside South Sudan. Inefficient regulation and poor gold outflows have helped make ASM an ideal target for capture by those who seek to finance armed groups, perpetrate violence, exploit mining communities, and exacerbate divisions. -

2019 Torit Multi-Sector Household Survey Report

2019 Torit Multi-Sector Household Survey Report February 2019 Contents RECENT OVERALL TRENDS and BASIC RECOMMENDATIONS ..................................................................... 4 BACKGROUND ............................................................................................................................................. 6 TORIT DASHBOARD ..................................................................................................................................... 7 COMMUNITY CONSOLE ............................................................................................................................ 10 I. PURPOSE, METHODOLOGY and SCOPE ............................................................................................. 11 PEOPLE WELFARE ...................................................................................................................................... 15 1. LIVELIHOOD ....................................................................................................................................... 15 2. MAIN PROBLEMS and RESILIENCE (COPING CAPACITY) ................................................................... 17 3. FOOD SECURITY................................................................................................................................. 19 4. HEALTH .............................................................................................................................................. 22 5. HYGIENE ........................................................................................................................................... -

Mineral Exploration and Sustainable Development: a Case Study in the Republic of South Sudan

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Earth and Environmental Sciences Earth and Environmental Sciences 2019 MINERAL EXPLORATION AND SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT: A CASE STUDY IN THE REPUBLIC OF SOUTH SUDAN Cosmas Pitia Kujjo University of Kentucky, [email protected] Author ORCID Identifier: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8314-7029 Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/etd.2019.061 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Kujjo, Cosmas Pitia, "MINERAL EXPLORATION AND SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT: A CASE STUDY IN THE REPUBLIC OF SOUTH SUDAN" (2019). Theses and Dissertations--Earth and Environmental Sciences. 64. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/ees_etds/64 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Earth and Environmental Sciences at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Earth and Environmental Sciences by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

Magwi County

Resettlement, Resource Conflicts, Livelihood Revival and Reintegration in South Sudan A study of the processes and institutional issues at the local level in Magwi County by N. Shanmugaratnam Noragric Department of International Environment and Development No. Report Noragric Studies 5 8 RESETTLEMENT, RESOURCE CONFLICTS, LIVELIHOOD REVIVAL AND REINTEGRATION IN SOUTH SUDAN A study of the processes and institutional issues at the local level in Magwi County By N. Shanmugaratnam Noragric Report No. 58 December 2010 Department of International Environment and Development Studies, Noragric Norwegian University of Life Sciences, UMB Noragric is the Department of International Environment and Development Studies at the Norwegian University of Life Sciences (UMB). Noragric’s activities include research, education and assignments, focusing particularly, but not exclusively, on developing countries and countries with economies in transition. Noragric Reports present findings from various studies and assignments, including programme appraisals and evaluations. This Noragric Report was commissioned by the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (Norad) under the framework agreement with UMB which is administrated by Noragric. Extracts from this publication may only be reproduced after prior consultation with the employer of the assignment (Norad) and with the consultant team leader (Noragric). The findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed in this publication are entirely those of the authors and cannot be attributed directly to the Department of International Environment and Development Studies (UMB/Noragric). Shanmugaratnam, N. Resettlement, resource conflicts, livelihood revival and reintegration in South Sudan: A study of the processes and institutional issues at the local level in Magwi County. Noragric Report No. 58 (December 2010) Department of International Environment and Development Studies, Noragric Norwegian University of Life Sciences (UMB) P.O. -

Challenges of Accountability an Assessment of Dispute Resolution Processes in Rural South Sudan

Challenges of Accountability An Assessment of Dispute Resolution Processes in Rural South Sudan By David K. Deng March 2013 Photos: David K. Deng This report presents findings from an assessment that the South Sudan Law Society (SSLS) conducted on the accessibility of local justice systems across six rural counties of South Sudan. The assessment included a comprehensive household survey that examined the legal needs of populations residing in the six counties and the legal services that are available to service those needs and numerous interviews with local justice service providers and users. David K. Deng is the author. Victor Bol provided research assistance. The views contained in this paper are those of the author alone. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the SSLS, Pact, or their donors. South Sudan Law Society (SSLS) Hai Thoura Juba, South Sudan Phone: +211 (0) 955 073 591 Email: [email protected] © 2012 South Sudan Law Society (SSLS) 1 About the South Sudan Law Society (SSLS) The South Sudan Law Society (SSLS) is a civil society organization based in Juba. Its mission is to strive for justice in society and respect for human rights and the rule of law in South Sudan. The SSLS manages projects in a number of areas, including legal aid, community paralegal training, human rights awareness-raising and capacity-building for legal professionals, traditional authorities and government institutions. Acknowledgements We would like to extend our profound appreciation to the wide range of people and organizations whose assistance made this report possible, first and foremost to the many government officials, community members, and legal professionals that took part in our interviews and surveys. -

Uganda Fighting for Decades

Southern Torit County Displacement and Service Access Brief Torit County, Eastern Equatoria State, South Sudan, November 2017 Background Map 1: Displacement in southern Torit County Major Town In response to reports of persistent needs and a growing population From Juba of Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) in the mountain and valley Assessed Village areas of southern Torit County, REACH joined a Rapid Response Mission team constituted by the World Food Program (WFP) and the Torit United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) in Gunyoro village, Ifwotu Payam. A concurrent screening and distribution took place in Iholong village, also in Ifwotu Payam, but was cut short due to nearby fighting. Gunyoro The assessment was conducted from 17-20 November and consisted of 4 KI interviews with community leaders, 2 gender-disaggregated Iholong Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) with a total of 28 participants, continuous interaction with community members during aid provision, Magwi and general observation of the area by foot and helicopter. Findings should be considered as indicative only, and further verification via site visits should occur where possible. Population Movement and Displacement Torit and the foothills of the Imatong Mountains to its south have seen To Uganda fighting for decades. In the last few years, the population in the area via Nimule has been in flux, with frequent displacement inflows and outflows, and nearly continuous internal movements. Imatong Mountains Displacement into southern Torit County Road Displacement to southern Torit County has been occurring Displacement to the area continuously since 2013, with two large waves following conflict in the Displacement within the area last few years. -

Final Resettlement Action Plan Report

Public Disclosure Authorized Upgrading of the NADAPAL-JUBA ROAD Public Disclosure Authorized from Gravel to Paved (Bitumen) Standards FINAL RESETTLEMENT ACTION PLAN REPORT Public Disclosure Authorized Issued on: November 6th, 2013 EMPLOYER: Ministry of Transport, Roads and Bridges, Government of Republic of South Sudan CONSULTANT: Public Disclosure Authorized SMEC INTERNATIONAL PTY LIMITED, AUSTRALIA REVISED BY: Ing. MRS. RITA OHENE SARFOH i | P a g e Table of Contents List of Tables ............................................................................................................................................. vi List of Figures ........................................................................................................................................ vi Acronyms ................................................................................................................................................. vii Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................... ix Chapter 1Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Background .................................................................................................................................. 1 1.2 The Statements of Objectives........................................................................................................ 2 1.3 Brief Description -

Review of Rinderpest Control in Southern Sudan 1989-2000

Review of Rinderpest Control in Southern Sudan 1989-2000 Prepared for the Community-based Animal Health and Epidemiology (CAPE) Unit of the Pan African Programme for the Control of Epizootics (PACE) Bryony Jones March 2001 Acknowledgements The information contained in this document has been collected over the years by southern Sudanese animal health workers, UNICEF/OLS Livestock Project staff, Tufts University consultants, and the staff of NGOs that have supported community-based animal health projects in southern Sudan (ACROSS, ACORD, ADRA, DOT, GAA, NPA, Oxfam-GB, Oxfam-Quebec, SC-UK, VETAID, VSF-B, VSF-CH, VSF-G, Vetwork Services Trust, World Relief). The individuals involved are too numerous to name, but their hard work and contribution of information is gratefully acknowledged. The data from the early years of the OLS Livestock Programme (1993 to 1996) was collated by Tim Leyland, formerly UNICEF/OLS Livestock Project Officer. Disease outbreak information from 1998 to date has been collated by Dr Gachengo Matindi, FAO/OLS Livestock Officer (formerly UNICEF/OLS Livestock Officer). Rinderpest serology and virus testing has mainly been carried out by National Veterinary Research Centre, Muguga, Nairobi. Any errors or omissions in this review are the fault of the author. If any reader has additional information to correct an error or omission the author would be grateful to receive this information. For further information contact: CAPE Unit PACE Programme OAU/IBAR PO Box 30786 Nairobi Tel: Nairobi 226447 Fax: Nairobi 226565 E mail: [email protected] Or the author: Bryony Jones PO Box 13434 Nairobi Kenya Tel: Nairobi 580799 E mail: [email protected] 2 CONTENTS Page 1. -

Symptoms and Causes: Insecurity and Underdevelopment in Eastern

sudanHuman Security Baseline Assessment issue brief Small Arms Survey Number 16 April 2010 Symptoms and causes Insecurity and underdevelopment in Eastern Equatoria astern Equatoria state (EES) is The survey was supplemented by qual- 24,789 (± 965) households in the one of the most volatile and itative interviews and focus group three counties contain at least one E conflict-prone states in South- discussions with key stakeholders in firearm. ern Sudan. An epicentre of the civil EES and Juba in January 2010. Respondents cited traditional lead- war (1983–2005), EES saw intense Key findings include: ers (clan elders and village chiefs) fighting between the Sudanese Armed as the primary security providers Across the entire sample, respond- Forces (SAF) and the Sudan People’s in their areas (90 per cent), followed ents ranked education and access Liberation Army (SPLA), as well by neighbours (48 per cent) and reli- to adequate health care as their numerous armed groups supported gious leaders (38 per cent). Police most pressing concerns, followed by both sides, leaving behind a legacy presence was only cited by 27 per by clean water. Food was also a top of landmines and unexploded ordnance, cent of respondents and the SPLA concern in Torit and Ikotos. Security high numbers of weapons in civilian by even fewer (6 per cent). ranked at or near the bottom of hands, and shattered social and com- Attitudes towards disarmament overall concerns in all counties. munity relations. were positive, with around 68 per When asked about their greatest EES has also experienced chronic cent of the total sample reporting a security concerns, respondents in food insecurity, a lack of basic services, willingness to give up their firearms, Torit and Ikotos cited cattle rustling, and few economic opportunities. -

Cultural Practices on Burial and Care for the Sick in South Sudan

Helpdesk Report Cultural practices on burial and care for the sick in South Sudan Iffat Idris GSDRC, University of Birmingham 17 September 2018 Question Carry out a rapid literature review on cultural practices in South Sudan on burial and caring for the sick, focusing on differences in practices across different ethnic groups. The main linguistic groupings and ethnic groups in each that are predominant in areas considered to be at highest risk of Ebola outbreak in South Sudan are: Bantu-speaking – Zande and Baka Bare-speaking – Moru, Kakwa, Pojulu, Kuku and Bare Others – Acholi, Madi, Lotuko, Toposa and Didinga Contents 1. Summary 2. Burial practices by ethnic group 3. Other relevant findings 4. References The K4D helpdesk service provides brief summaries of current research, evidence, and lessons learned. Helpdesk reports are not rigorous or systematic reviews; they are intended to provide an introduction to the most important evidence related to a research question. They draw on a rapid desk-based review of published literature and consultation with subject specialists. Helpdesk reports are commissioned by the UK Department for International Development and other Government departments, but the views and opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect those of DFID, the UK Government, K4D or any other contributing organisation. For further information, please contact [email protected]. 1. Summary Literature on cultural practices for burial and care for the sick among individual ethnic groups in South Sudan was very limited. However, it clearly points to the importance of proper burials among all ethnic groups: these typically entail washing the body of the deceased; it can take several days before burial takes place; and graves are often located within or close to family homesteads. -

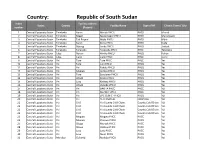

Operational Deployment Plan Template

Country: Republic of South Sudan Index Facility Address States County Facility Name Type of HF Closest Town / City number (Payam) 1 Central Equatoria State Terekeka Nyori Moridi PHCU PHCU Moridi 2 Central Equatoria State Terekeka Reggo Makamagor PHCU PHCU Makamagor 3 Central Equatoria State Terekeka Tali Payam Mijiki PHCU PHCU Mijiki 4 Central Equatoria State Terekeka Nyori Kuda PHCU PHCU Kuda 5 Central Equatoria State Terekeka Rijiong Jonko PHCU PHCU Jonkok 6 Central Equatoria State Terekeka Terekeka Terekeka PHCC PHCC Terekeka 7 Central Equatoria State Juba Rokon Miriko PHCU PHCU Rokon 8 Central Equatoria State Juba Ganji Ganji PHCC PHCC Ganji 9 Central Equatoria State Yei Tore Tore PHCC PHCC Yei 10 Central Equatoria State Yei Tore Goli PHCU PHCU Yei 11 Central Equatoria State Yei Yei Pakula PHCU PHCU Yei 12 Central Equatoria State Yei Mugwo Jombu PHCU PHCU Yei 13 Central Equatoria State Yei Tore Bandame PHCU PHCU Yei 14 Central Equatoria State Yei Otogo Kejiko PHCU PHCU Yei 15 Central Equatoria State Yei Lasu Kirikwa PHCU PHCU Yei 16 Central Equatoria State Yei Otogo Rubeke PHCU PHCU Yei 17 Central Equatoria State Yei Yei BAKITA PHCC PHCC YEI 18 Central Equatoria State Yei Yei Marther PHCC PHCC YEI 19 Central Equatoria State Yei Yei EPC CLINIC - PHCU PHCU YEI 20 Central Equatoria State Yei Yei YEI HOSPITAL HOSPITAL YEI 21 Central Equatoria State Yei CHD Yei County Cold Chain County Cold Chain YEI 22 Central Equatoria State Yei CHD Yei County Cold Chain County Cold Chain YEI 23 Central Equatoria State Yei CHD Yei County Cold Chain County -

South Sudan Country Operational Plan (COP)

FY 2015 South Sudan Country Operational Plan (COP) The following elements included in this document, in addition to “Budget and Target Reports” posted separately on www.PEPFAR.gov, reflect the approved FY 2015 COP for South Sudan. 1) FY 2015 COP Strategic Development Summary (SDS) narrative communicates the epidemiologic and country/regional context; methods used for programmatic design; findings of integrated data analysis; and strategic direction for the investments and programs. Note that PEPFAR summary targets discussed within the SDS were accurate as of COP approval and may have been adjusted as site- specific targets were finalized. See the “COP 15 Targets by Subnational Unit” sheets that follow for final approved targets. 2) COP 15 Targets by Subnational Unit includes approved COP 15 targets (targets to be achieved by September 30, 2016). As noted, these may differ from targets embedded within the SDS narrative document and reflect final approved targets. Approved FY 2015 COP budgets by mechanism and program area, and summary targets are posted as a separate document on www.PEPFAR.gov in the “FY 2015 Country Operational Plan Budget and Target Report.” South Sudan Country/Regional Operational Plan (COP/ROP) 2015 Strategic Direction Summary August 27, 2015 Table of Contents Goal Statement 1.0 Epidemic, Response, and Program Context 1.1 Summary statistics, disease burden and epidemic profile 1.2 Investment profile 1.3 Sustainability Profile 1.4 Alignment of PEPFAR investments geographically to burden of disease 1.5 Stakeholder engagement