Eastern Equatoria)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ss 9303 Ee Kapoeta North Cou

SOUTH SUDAN Kapoeta North County reference map SUDAN Pibor JONGLEI ETHIOPIA CAR DRC KENYA UGANDA EASTERN EQUATORIA Kenyi Lafon Kapoeta East Akitukomoi Kangitabok Lomokori Kapoeta North Ngigalingatun Kangibun Kalopedet Lokidangoai Nomogonjet Nawitapal Mogos Chokagiling Lorutuk Lokoges Nakwa Owetiani Nawabei Natatur Kamaliato Kanyowokol Karibungura Lokale Nagira Belengtobok Tuliabok Lokorechoke Kadapangolol Akoribok Nakwaparich Kalobeliang Wana Kachinga Lomus Lotiakara Pucwa Lopetet Nawao Lokorilam Naduket Tingayta Lodomei Kibak Nakatiti International boundary Nakapangiteng Napusiret Napulak State boundary Loriwo County boundary Kochoto Naminitotit Parpar Undetermined boundary Napusireit Nakwamoru Abyei region Kotak Kasotongor Napochorege Katiakin Nawayareng Riwoto Lokorumor Country capital Nangoletire Lokualem Lumeyen Logerain Lomidila Takankim Lobei Administrative centre/County capital Lokwamor Nacukut Naronyi Nakoret Lotiekar Namukeris Principal town Napotit Naoyatir Nakore Napureit Secondary town Lokwamiro Narubui Barach Lolepon Lotiri Paima Village Loregai Narongyet Lochuloit Kabuni Primary road Kudule Locheler Napusiria Napotpot Secondary road Nacholobo Tertiary road Budi Idong Main river Kapoeta South 0 5 10 km The administrative boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. Final boundary between the Republic of Sudan and the Republic of South Sudan has not yet been determined. Final status of Abyei area is not yet determined. Created: March 2020 | Code: SS-9303 | Sources: OCHA, SSNBS | Feedback: [email protected] | unocha.org/south-sudan | reliefweb.int/country/ssd | southsudan.humanitarianresponse.info . -

The Criminalization of South Sudan's Gold Sector

The Criminalization of South Sudan’s Gold Sector Kleptocratic Networks and the Gold Trade in Kapoeta By the Enough Project April 2020* A Precious Resource in an Arid Land Within the area historically known as the state of Eastern Equatoria, Kapoeta is a semi-arid rangeland of clay soil dotted with short, thorny shrubs and other vegetation.1 Precious resources lie below this desolate landscape. Eastern Equatoria, along with the region historically known as Central Equatoria, contains some of the most important and best-known sites for artisanal and small-scale gold mining (ASM). Some estimates put the number of miners at 60,000 working at 80 different locations in the area, including Nanaknak, Lauro (Didinga Hills), Napotpot, and Namurnyang. Locals primarily use traditional mining techniques, panning for gold from seasonal streams in various villages. The work provides miners’ families resources to support their basic needs.2 Kapoeta’s increasingly coveted gold resources are being smuggled across the border into Kenya with the active complicity of local and national governments. This smuggling network, which involves international mining interests, has contributed to increased militarization.3 Armed actors and corrupt networks are fueling low-intensity conflicts over land, particularly over the ownership of mining sites, and causing the militarization of gold mining in the area. Poor oversight and conflicts over the control of resources between the Kapoeta government and the national government in Juba enrich opportunistic actors both inside and outside South Sudan. Inefficient regulation and poor gold outflows have helped make ASM an ideal target for capture by those who seek to finance armed groups, perpetrate violence, exploit mining communities, and exacerbate divisions. -

Conflict and Crisis in South Sudan's Equatoria

SPECIAL REPORT NO. 493 | APRIL 2021 UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE www.usip.org Conflict and Crisis in South Sudan’s Equatoria By Alan Boswell Contents Introduction ...................................3 Descent into War ..........................4 Key Actors and Interests ............ 9 Conclusion and Recommendations ...................... 16 Thomas Cirillo, leader of the Equatoria-based National Salvation Front militia, addresses the media in Rome on November 2, 2019. (Photo by Andrew Medichini/AP) Summary • In 2016, South Sudan’s war expand- Equatorians—a collection of diverse South Sudan’s transitional period. ed explosively into the country’s minority ethnic groups—are fighting • On a national level, conflict resolu- southern region, Equatoria, trig- for more autonomy, local or regional, tion should pursue shared sover- gering a major refugee crisis. Even and a remedy to what is perceived eignty among South Sudan’s con- after the 2018 peace deal, parts of as (primarily) Dinka hegemony. stituencies and regions, beyond Equatoria continue to be active hot • Equatorian elites lack the external power sharing among elites. To spots for national conflict. support to viably pursue their ob- resolve underlying grievances, the • The war in Equatoria does not fit jectives through violence. The gov- political process should be expand- neatly into the simplified narratives ernment in Juba, meanwhile, lacks ed to include consultations with of South Sudan’s war as a power the capacity and local legitimacy to local community leaders. The con- struggle for the center; nor will it be definitively stamp out the rebellion. stitutional reform process of South addressed by peacebuilding strate- Both sides should pursue a nego- Sudan’s current transitional period gies built off those precepts. -

Figure 1. Southern Sudan's Protected Areas

United Nations Development Programme Country: Sudan PROJECT DOCUMENT Launching Protected Area Network Management and Building Capacity in Post-conflict Project Title: Southern Sudan By end of 2012, poverty especially among vulnerable groups is reduced and equitable UNDAF economic growth is increased through improvements in livelihoods, food security, decent Outcome(s): employment opportunities, sustainable natural resource management and self reliance; UNDP Strategic Plan Environment and Sustainable Development Primary Outcome: Catalyzing access to environmental finance UNDP Strategic Plan Secondary Outcome: Mainstreaming environment and energy Expected CP Outcome(s): Strengthened capacity of national, sub-national, state and local institutions and communities to manage the environment and natural disasters to reduce conflict over natural resources Expected CPAP Output(s) 1. National and sub-national, state and local institutions and communities capacities for effective environmental governance, natural resources management, conflict and disaster risk reduction enhanced. 2. Comprehensive strategic frameworks developed at national and sub-national levels regarding environment and natural resource management Executing Entity/Implementing Partner: NGO Execution Modality – WCS in cooperation with the Ministry of Wildlife Conservation and Tourism of the Government of Southern Sudan (MWCT-GoSS) Implementing Entity/Responsible Partners: United Nations Development Programme Brief Description The current situation Despite the 1983 to 2005 civil war, many areas of Southern Sudan still contain areas of globally significant habitats and wildlife populations. For example, Southern Sudan contains one of the largest untouched savannah and woodland ecosystems remaining in Africa as well as the Sudd, the largest wetland in Africa, of inestimable value to the flow of the River Nile, the protection of endemic species and support of local livelihoods. -

Cholera Situation Analysis and Hotspot Mapping in South Sudan

GTFCC Meeting for the Working Groups on CHOLERA SITUATION ANALYSIS Surveillance AND HOTSPOT MAPPING IN (Epidemiology and Laboratory) (15th to 17th SOUTH SUDAN March 2019) BACKGROUN D 1. South Sudan borders Uganda, Kenya, Ethiopia, Sudan, DR Congo, & CAR 2. Got independence in 2011 3. Protracted Grade 3 crisis since 2013 (situation improving since Sept 2018) 4. Severe food insecurity – 7.1million (63% of population) – 45,000 faced with famine 5. 1.87 million IDPs & 2.27million refugees to neighboring countries 1. Multisectoral taskforce in place chaired by MoH with the other sectors (Water & COORDINATION OF Humanitarian Affairs) and partners (Health + WASH) CHOLERA CONTROL clusters as members 2. Draft National Cholera Control Plan pending WASH assessment & stakeholder review/costing 3. Implemented preventive OCV campaigns since 2017 (2.9 million doses approved 27/Mar/2019) 4. Sub-optimal involvement of other sectors and WASH in OCV preventive campaigns CHOLERA IN SOUTH 1. South Sudan endemic for SUDANcholera 2. Since the 2013 crisis onset – cholera outbreaks – 2014 - 2017 3. Between 2014-2017 at least 28,676 cases & 644 deaths reported 4. All outbreaks started in Juba 5. Cases reported along River Nile, cattle camps, IDPs, islands, & Commercial hubs 1600 Cholera cases in South Sudan, 2014 s e s a 1200 Cholera cases in South Sudan, 2014 s c e f s a o 2014 c f r 800 o 2014 e 1000 r e b b m 400 m CHOLERA IN u u N N 0 0 1 3 5 7 9 111315171921232527293133353739414345474951 1 3 5 7 9 111315171921232527293133353739414345474951 Week of onset Week of onset 1900 Cholera cases in South Sudan, 2015 s e s SOUTH a c 1600 Cholera cases in South Sudan, 2015 f o s r 900 e e 2015 b s m a 1200 u c N f o -100 r 800 1 3 5 7 9 111315171921232527293133353739414345474951 SUDAN e 2015 Week of onset b m 400 u Cholera cases in South Sudan, 2016 s N e 1600 s a 0 c f 1200 1. -

Linkages-Success-Stories-South-Sudan

JULY 2016 SUCCESS STORY Success on Several Levels in South Sudan In South Sudan, obtaining HIV care and treatment is difficult for people living with HIV. Only 10 percent of those eligible are currently enrolled on antiretroviral therapy (ART). But for one key population — female sex workers (FSWs) — the barriers to comprehensive HIV care and treatment are particularly daunting. Many sex workers cannot afford to lose income while waiting for services at overburdened hospitals. And those who do seek care often find providers are reluctant to serve them because of the stigma associated with sex work. Recruiting and retaining FSWs and other key populations (KPs) into the HIV cascade of services is a complex issue that demands a response at many levels. In South Sudan, LINKAGES is helping to generate a demand for services, improve access to KP-friendly services, and create a policy environment that is more conducive to the health rights of key populations. GENERATING DEMAND FOR SERVICES The justified mistrust that FSWs have for the health care system keeps many from seeking the services they need. Peer education and outreach is a critical component of engaging KPs in the HIV cascade. LINKAGES South Sudan conducted a mapping exercise to identify hotspots (or key locations) where sex work takes place. From these locations, 65 FSWs were identified and trained as peer educators to lead participatory education sessions among their peers. The sessions are designed to motivate FSWs to adopt healthy behaviors and develop the skills to do so. The sessions cover topics like condom use, regular screening and treatment for sexually transmitted infections (STIs), periodic testing for HIV, and enrollment into care and treatment services for those living with HIV. -

Mineral Exploration and Sustainable Development: a Case Study in the Republic of South Sudan

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Earth and Environmental Sciences Earth and Environmental Sciences 2019 MINERAL EXPLORATION AND SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT: A CASE STUDY IN THE REPUBLIC OF SOUTH SUDAN Cosmas Pitia Kujjo University of Kentucky, [email protected] Author ORCID Identifier: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8314-7029 Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/etd.2019.061 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Kujjo, Cosmas Pitia, "MINERAL EXPLORATION AND SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT: A CASE STUDY IN THE REPUBLIC OF SOUTH SUDAN" (2019). Theses and Dissertations--Earth and Environmental Sciences. 64. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/ees_etds/64 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Earth and Environmental Sciences at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Earth and Environmental Sciences by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

Magwi County

Resettlement, Resource Conflicts, Livelihood Revival and Reintegration in South Sudan A study of the processes and institutional issues at the local level in Magwi County by N. Shanmugaratnam Noragric Department of International Environment and Development No. Report Noragric Studies 5 8 RESETTLEMENT, RESOURCE CONFLICTS, LIVELIHOOD REVIVAL AND REINTEGRATION IN SOUTH SUDAN A study of the processes and institutional issues at the local level in Magwi County By N. Shanmugaratnam Noragric Report No. 58 December 2010 Department of International Environment and Development Studies, Noragric Norwegian University of Life Sciences, UMB Noragric is the Department of International Environment and Development Studies at the Norwegian University of Life Sciences (UMB). Noragric’s activities include research, education and assignments, focusing particularly, but not exclusively, on developing countries and countries with economies in transition. Noragric Reports present findings from various studies and assignments, including programme appraisals and evaluations. This Noragric Report was commissioned by the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (Norad) under the framework agreement with UMB which is administrated by Noragric. Extracts from this publication may only be reproduced after prior consultation with the employer of the assignment (Norad) and with the consultant team leader (Noragric). The findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed in this publication are entirely those of the authors and cannot be attributed directly to the Department of International Environment and Development Studies (UMB/Noragric). Shanmugaratnam, N. Resettlement, resource conflicts, livelihood revival and reintegration in South Sudan: A study of the processes and institutional issues at the local level in Magwi County. Noragric Report No. 58 (December 2010) Department of International Environment and Development Studies, Noragric Norwegian University of Life Sciences (UMB) P.O. -

Challenges of Accountability an Assessment of Dispute Resolution Processes in Rural South Sudan

Challenges of Accountability An Assessment of Dispute Resolution Processes in Rural South Sudan By David K. Deng March 2013 Photos: David K. Deng This report presents findings from an assessment that the South Sudan Law Society (SSLS) conducted on the accessibility of local justice systems across six rural counties of South Sudan. The assessment included a comprehensive household survey that examined the legal needs of populations residing in the six counties and the legal services that are available to service those needs and numerous interviews with local justice service providers and users. David K. Deng is the author. Victor Bol provided research assistance. The views contained in this paper are those of the author alone. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the SSLS, Pact, or their donors. South Sudan Law Society (SSLS) Hai Thoura Juba, South Sudan Phone: +211 (0) 955 073 591 Email: [email protected] © 2012 South Sudan Law Society (SSLS) 1 About the South Sudan Law Society (SSLS) The South Sudan Law Society (SSLS) is a civil society organization based in Juba. Its mission is to strive for justice in society and respect for human rights and the rule of law in South Sudan. The SSLS manages projects in a number of areas, including legal aid, community paralegal training, human rights awareness-raising and capacity-building for legal professionals, traditional authorities and government institutions. Acknowledgements We would like to extend our profound appreciation to the wide range of people and organizations whose assistance made this report possible, first and foremost to the many government officials, community members, and legal professionals that took part in our interviews and surveys. -

Mining in South Sudan: Opportunities and Risks for Local Communities

» REPORT JANUARY 2016 MINING IN SOUTH SUDAN: OPPORTUNITIES AND RISKS FOR LOCAL COMMUNITIES BASELINE ASSESSMENT OF SMALL-SCALE AND ARTISANAL GOLD MINING IN CENTRAL AND EASTERN EQUATORIA STATES, SOUTH SUDAN MINING IN SOUTH SUDAN FOREWORD We are delighted to present you the findings of an assessment conducted between February and May 2015 in two states of South Sudan. With this report, based on dozens of interviews, focus group discussions and community meetings, a multi-disciplinary team of civil society and government representatives from South Sudan are for the first time shedding light on the country’s artisanal and small-scale mining sector. The picture that emerges is a remarkable one: artisanal gold mining in South Sudan ‘employs’ more than 60,000 people and might indirectly benefit almost half a million people. The vast majority of those involved in artisanal mining are poor rural families for whom alluvial gold mining provides critical income to supplement their subsistence livelihood of farming and cattle rearing. Ostensibly to boost income for the cash-strapped government, artisanal mining was formalized under the Mining Act and subsequent Mineral Regulations. However, owing to inadequate information-sharing and a lack of government mining sector staff at local level, artisanal miners and local communities are not aware of these rules. In reality there is almost no official monitoring of artisanal or even small-scale mining activities. Despite the significant positive impact on rural families’ income, the current form of artisanal mining does have negative impacts on health, the environment and social practices. With most artisanal, small-scale and exploration mining taking place in rural areas with abundant small arms and limited presence of government security forces, disputes over land access and ownership exacerbate existing conflicts. -

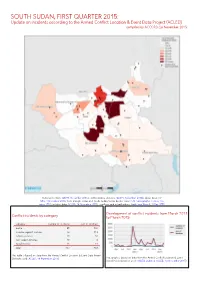

SOUTH SUDAN, FIRST QUARTER 2015: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 26 November 2015

SOUTH SUDAN, FIRST QUARTER 2015: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 26 November 2015 National borders: GADM, November 2015a; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015b; Abyei Area: SS- NBS, 1 December 2008; Ilemi triangle status and South Sudan/Sudan border status: UN Cartographic Section, Oc- tober 2011; incident data: ACLED, 14 November 2015; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 Development of conflict incidents from March 2013 Conflict incidents by category to March 2015 category number of incidents sum of fatalities battle 85 596 violence against civilians 52 113 remote violence 21 16 non-violent activities 18 2 riots/protests 16 11 total 192 738 This table is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (datasets used: ACLED, 14 November 2015). This graph is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (datasets used: ACLED, undated, ACLED, 14 November 2015). SOUTH SUDAN, FIRST QUARTER 2015: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 26 NOVEMBER 2015 LOCALIZATION OF CONFLICT INCIDENTS Note: The following list is an overview of the incident data included in the ACLED dataset. More details are available in the actual dataset (date, location data, event type, involved actors, information sources, etc.). In the following list, the names of event locations are taken from ACLED, while the administrative region names are taken from GADM data which serves as the basis for the map above. Data on incidents in the Abyei area are not reflected in this update. -

Water for Eastern Equatoria (W4EE)

Water for Eastern Equatoria (W4EE) he first integrated water resource management (IWRM) project of its kind in South Sudan, Water Water for Eastern for Eastern Equatoria (W4EE) was launched in Components 2013 as part of the broader bilateral water Tprogramme funded through the Dutch Multiannual Equatoria (W4EE) Strategic Plan for South Sudan (2012–2015). W4EE focuses on three interrelated From the very beginning, W4EE was planned as a pilot components: IWRM programme in the Torit and Kapoeta States of The role of integrated water resource manage- Eastern Equatoria focusing on holistic management of the ment in fostering resilience, delivering economic Kenneti catchment, conflict-sensitive oversight of water Component 1: Integrated water resource management of the development, improving health, and promoting for productive use such as livestock and farming, and Kenneti catchment and surrounds peace in a long-term process. improved access to safe drinking water as well as sanitati- on and hygiene. The goal has always been to replicate key Component 2: Conflict-sensitive management of water for learnings and best practice in other parts of South Sudan. productive use contributes to increased, sustained productivity, value addition in agriculture, horticulture, and livestock The Kenneti catchment is very important to the Eastern Equatoria region for economic, social, and biodiversity reasons. The river has hydropower potential, supports the Component 3: Safely managed and climate-resilient drinking livelihoods of thousands of households, and the surroun- water services and improved sanitation and hygiene are available, ding area hosts a national park with forests and wetlands operated and maintained in a sustainable manner. as well as wild animals and migratory birds.