Factors Hindering Didinga Women's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Criminalization of South Sudan's Gold Sector

The Criminalization of South Sudan’s Gold Sector Kleptocratic Networks and the Gold Trade in Kapoeta By the Enough Project April 2020* A Precious Resource in an Arid Land Within the area historically known as the state of Eastern Equatoria, Kapoeta is a semi-arid rangeland of clay soil dotted with short, thorny shrubs and other vegetation.1 Precious resources lie below this desolate landscape. Eastern Equatoria, along with the region historically known as Central Equatoria, contains some of the most important and best-known sites for artisanal and small-scale gold mining (ASM). Some estimates put the number of miners at 60,000 working at 80 different locations in the area, including Nanaknak, Lauro (Didinga Hills), Napotpot, and Namurnyang. Locals primarily use traditional mining techniques, panning for gold from seasonal streams in various villages. The work provides miners’ families resources to support their basic needs.2 Kapoeta’s increasingly coveted gold resources are being smuggled across the border into Kenya with the active complicity of local and national governments. This smuggling network, which involves international mining interests, has contributed to increased militarization.3 Armed actors and corrupt networks are fueling low-intensity conflicts over land, particularly over the ownership of mining sites, and causing the militarization of gold mining in the area. Poor oversight and conflicts over the control of resources between the Kapoeta government and the national government in Juba enrich opportunistic actors both inside and outside South Sudan. Inefficient regulation and poor gold outflows have helped make ASM an ideal target for capture by those who seek to finance armed groups, perpetrate violence, exploit mining communities, and exacerbate divisions. -

South Sudan's

Untapped and Unprepared Dirty Deals Threaten South Sudan’s Mining Sector April 2020 Table of Contents Executive Summary 1 Invitation to Exploitation 4 Beneath the Battlefield: Mineral Development During Conflict 12 Indications of Possible Money Laundering 19 Recommendations 20 We are grateful for the support we receive from our donors who have helped make our work possible. To learn more about The Sentry’s funders, please visit The Sentry website at www.thesentry.org/about/. UNTAPPED AND UNPREPARED: DIRTY DEALS THREATEN SOUTH SUDAN’S MINING SECTOR TheSentry.org Executive Summary South Sudan’s mining sector has seen rapid development in recent years, and preliminary reports suggest that the industry could become an engine for major economic growth. However, ineffective accountability mechanisms, an opaque corporate landscape, and inadequate due diligence have exposed the sector to abuse by bad actors within South Sudan’s ruling clique. The Sentry has found that existing laws have proven insufficient bulwarks against abuse, raising concerns that the country’s mineral wealth could do little more than spur the kind of violent competition that has ravaged the oil sector. Although South Sudan took welcome steps to reform the mining sector in 2012, some government officials, their relatives, and their close associates have fostered a weak regulatory environment susceptible to exploitation. In one example of how the privileged few have apparently exploited kleptocratic arrangements, President Salva Kiir’s daughter partly owns a company with three active licenses, while another company with three licenses lists former Vice President James Wani Igga’s son as a shareholder. Ashraf Seed Ahmed Hussein Ali, a businessman commonly known as Al-Cardinal who was placed under Global Magnitsky sanctions in October 2019, reportedly owns the company currently holding the greatest number of licenses.1 In the gold-rich region of Kapoeta, state government officials have begun issuing licenses independently of the central government. -

The Role of Indigenous Languages in Southern Sudan: Educational Language Policy and Planning

The Role of Indigenous Languages in Southern Sudan: Educational Language Policy and Planning H. Wani Rondyang A thesis submitted to the Institute of Education, University of London, for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2007 Abstract This thesis aims to questions the language policy of Sudan's central government since independence in 1956. An investigation of the root causes of educational problems, which are seemingly linked to the current language policy, is examined throughout the thesis from Chapter 1 through 9. In specific terms, Chapter 1 foregrounds the discussion of the methods and methodology for this research purposely because the study is based, among other things, on the analysis of historical documents pertaining to events and processes of sociolinguistic significance for this study. The factors and sociolinguistic conditions behind the central government's Arabicisation policy which discourages multilingual development, relate the historical analysis in Chapter 3 to the actual language situation in the country described in Chapter 4. However, both chapters are viewed in the context of theoretical understanding of language situation within multilingualism in Chapter 2. The thesis argues that an accommodating language policy would accord a role for the indigenous Sudanese languages. By extension, it would encourage the development and promotion of those languages and cultures in an essentially linguistically and culturally diverse and multilingual country. Recommendations for such an alternative educational language policy are based on the historical and sociolinguistic findings in chapters 3 and 4 as well as in the subsequent discussions on language policy and planning proper in Chapters 5, where theoretical frameworks for examining such issues are explained, and Chapters 6 through 8, where Sudan's post-independence language policy is discussed. -

Mineral Exploration and Sustainable Development: a Case Study in the Republic of South Sudan

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Earth and Environmental Sciences Earth and Environmental Sciences 2019 MINERAL EXPLORATION AND SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT: A CASE STUDY IN THE REPUBLIC OF SOUTH SUDAN Cosmas Pitia Kujjo University of Kentucky, [email protected] Author ORCID Identifier: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8314-7029 Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/etd.2019.061 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Kujjo, Cosmas Pitia, "MINERAL EXPLORATION AND SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT: A CASE STUDY IN THE REPUBLIC OF SOUTH SUDAN" (2019). Theses and Dissertations--Earth and Environmental Sciences. 64. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/ees_etds/64 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Earth and Environmental Sciences at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Earth and Environmental Sciences by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

Political Repression in Sudan

Sudan Page 1 of 243 BEHIND THE RED LINE Political Repression in Sudan Human Rights Watch/Africa Human Rights Watch Copyright © May 1996 by Human Rights Watch. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 96-75962 ISBN 1-56432-164-9 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This report was researched and written by Human Rights Watch Counsel Jemera Rone. Human Rights Watch Leonard H. Sandler Fellow Brian Owsley also conducted research with Ms. Rone during a mission to Khartoum, Sudan, from May 1-June 13, 1995, at the invitation of the Sudanese government. Interviews in Khartoum with nongovernment people and agencies were conducted in private, as agreed with the government before the mission began. Private individuals and groups requested anonymity because of fear of government reprisals. Interviews in Juba, the largest town in the south, were not private and were controlled by Sudan Security, which terminated the visit prematurely. Other interviews were conducted in the United States, Cairo, London and elsewhere after the end of the mission. Ms. Rone conducted further research in Kenya and southern Sudan from March 5-20, 1995. The report was edited by Deputy Program Director Michael McClintock and Human Rights Watch/Africa Executive Director Peter Takirambudde. Acting Counsel Dinah PoKempner reviewed sections of the manuscript and Associate Kerry McArthur provided production assistance. This report could not have been written without the assistance of many Sudanese whose names cannot be disclosed. CONTENTS -

Challenges of Accountability an Assessment of Dispute Resolution Processes in Rural South Sudan

Challenges of Accountability An Assessment of Dispute Resolution Processes in Rural South Sudan By David K. Deng March 2013 Photos: David K. Deng This report presents findings from an assessment that the South Sudan Law Society (SSLS) conducted on the accessibility of local justice systems across six rural counties of South Sudan. The assessment included a comprehensive household survey that examined the legal needs of populations residing in the six counties and the legal services that are available to service those needs and numerous interviews with local justice service providers and users. David K. Deng is the author. Victor Bol provided research assistance. The views contained in this paper are those of the author alone. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the SSLS, Pact, or their donors. South Sudan Law Society (SSLS) Hai Thoura Juba, South Sudan Phone: +211 (0) 955 073 591 Email: [email protected] © 2012 South Sudan Law Society (SSLS) 1 About the South Sudan Law Society (SSLS) The South Sudan Law Society (SSLS) is a civil society organization based in Juba. Its mission is to strive for justice in society and respect for human rights and the rule of law in South Sudan. The SSLS manages projects in a number of areas, including legal aid, community paralegal training, human rights awareness-raising and capacity-building for legal professionals, traditional authorities and government institutions. Acknowledgements We would like to extend our profound appreciation to the wide range of people and organizations whose assistance made this report possible, first and foremost to the many government officials, community members, and legal professionals that took part in our interviews and surveys. -

Crossing Lines: “Magnets” and Mobility Among Southern Sudanese

“Magnets” andMobilityamongSouthernSudanese Crossing Lines United States Agency for InternationalDevelopment Agency for United States Contract No. HNE-I-00-00-00038-00 BEPS Basic Education and Policy Support (BEPS) Activity CREATIVE ASSOCIATES INTERNATIONAL INC In collaboration with CARE, THE GEORGE WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY, AND GROUNDWORK Crossing Lines “Magnets” and Mobility among Southern Sudanese A final report of two assessment trips examining the impact and broader implications of a new teacher training center in the Kakuma refugee camps, Kenya Prepared by: Marc Sommers Youth at Risk Specialist, CARE Basic Education and Policy Support Activity (BEPS) CARE, Inc. 151 Ellis Street, NE Atlanta, GA 30303-2439 and Creative Associates International, Inc. 5301 Wisconsin Avenue, NW Suite 700 Washington, DC 20015 Prepared for: Basic Education and Policy Support (BEPS) Activity US Agency for International Development Contract No. HNE-I-00-00-00038-00 Creative Associates International, Inc., Prime Contractor Photo credit: Marc Sommers 2002 Crossing Lines: “Magnets” and Mobility among Southern Sudanese CONTENTS I. Introduction: Do Education Facilities Attract Displaced People? The Current Debate .........................................................................................................................1 II. Background: Why Study Teacher Training in Kakuma and Southern Sudan? ......... 3 III. Findings: Issues Related to Mobility in Southern Sudan........................................... 8 A. Institutions at Odds: Contrasting Perceptions........................................................ -

Mining in South Sudan: Opportunities and Risks for Local Communities

» REPORT JANUARY 2016 MINING IN SOUTH SUDAN: OPPORTUNITIES AND RISKS FOR LOCAL COMMUNITIES BASELINE ASSESSMENT OF SMALL-SCALE AND ARTISANAL GOLD MINING IN CENTRAL AND EASTERN EQUATORIA STATES, SOUTH SUDAN MINING IN SOUTH SUDAN FOREWORD We are delighted to present you the findings of an assessment conducted between February and May 2015 in two states of South Sudan. With this report, based on dozens of interviews, focus group discussions and community meetings, a multi-disciplinary team of civil society and government representatives from South Sudan are for the first time shedding light on the country’s artisanal and small-scale mining sector. The picture that emerges is a remarkable one: artisanal gold mining in South Sudan ‘employs’ more than 60,000 people and might indirectly benefit almost half a million people. The vast majority of those involved in artisanal mining are poor rural families for whom alluvial gold mining provides critical income to supplement their subsistence livelihood of farming and cattle rearing. Ostensibly to boost income for the cash-strapped government, artisanal mining was formalized under the Mining Act and subsequent Mineral Regulations. However, owing to inadequate information-sharing and a lack of government mining sector staff at local level, artisanal miners and local communities are not aware of these rules. In reality there is almost no official monitoring of artisanal or even small-scale mining activities. Despite the significant positive impact on rural families’ income, the current form of artisanal mining does have negative impacts on health, the environment and social practices. With most artisanal, small-scale and exploration mining taking place in rural areas with abundant small arms and limited presence of government security forces, disputes over land access and ownership exacerbate existing conflicts. -

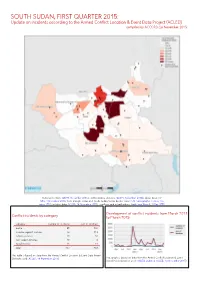

SOUTH SUDAN, FIRST QUARTER 2015: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 26 November 2015

SOUTH SUDAN, FIRST QUARTER 2015: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 26 November 2015 National borders: GADM, November 2015a; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015b; Abyei Area: SS- NBS, 1 December 2008; Ilemi triangle status and South Sudan/Sudan border status: UN Cartographic Section, Oc- tober 2011; incident data: ACLED, 14 November 2015; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 Development of conflict incidents from March 2013 Conflict incidents by category to March 2015 category number of incidents sum of fatalities battle 85 596 violence against civilians 52 113 remote violence 21 16 non-violent activities 18 2 riots/protests 16 11 total 192 738 This table is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (datasets used: ACLED, 14 November 2015). This graph is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (datasets used: ACLED, undated, ACLED, 14 November 2015). SOUTH SUDAN, FIRST QUARTER 2015: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 26 NOVEMBER 2015 LOCALIZATION OF CONFLICT INCIDENTS Note: The following list is an overview of the incident data included in the ACLED dataset. More details are available in the actual dataset (date, location data, event type, involved actors, information sources, etc.). In the following list, the names of event locations are taken from ACLED, while the administrative region names are taken from GADM data which serves as the basis for the map above. Data on incidents in the Abyei area are not reflected in this update. -

United Nations Nations Unies

United Nations Nations Unies Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs Humanitarian Coordinator in South Sudan condemns killing of an aid worker in Budi, Eastern Equatoria (Juba, 13 May 2021) The Humanitarian Coordinator in South Sudan, Alain Noudéhou, has condemned the killing of an aid worker in Budi, Eastern Equatoria, and called for authorities and communities to ensure that humanitarian personnel can move safely along roads and deliver assistance to the most vulnerable people. On 12 May, an aid worker was killed when criminals fired at a clearly marked humanitarian vehicle. The vehicle was part of a team of international non-governmental organizations and South Sudanese government health workers traveling to a health facility. The team was driving from Chukudum to Kapoeta in Budi County in an area that has seen several roadside ambushes this year. “I am shocked by this violent act and send my condolences to the family and colleagues of the deceased. The roads are a vital connection between humanitarian organizations and communities in need, and we must be able to move safely across the country without fear,” Mr. Noudéhou said and added: “I call on the Government to strengthen law enforcement along these roads.” This is the first aid worker killed in South Sudan in 2021. In 2020, nine aid workers were killed. *** Note to editors To learn more about humanitarian access in South Sudan, see the first quarterly access snapshot of 2021 here: https://bit.ly/3dZQtGw For further information, please contact: Emmi Antinoja, Head of Communications and Information Management, +211 92 129 6333 [email protected] Anthony Burke, Public Information Officer, +211 92 240 6014 and [email protected] OCHA press releases are available at www.unocha.org/south-sudan or www.reliefweb.int. -

Bringing HOPE to South Sudan

2019 Annual Report one of the most ethnically and cultur- ally diverse countries on the continent Our Missionary Family of Africa. Estimates of the Toposa tribesmen (to whom H4S ministers) Bringing vary widely. They are traditionally livestock herders. Wealth is measured in terms of how many cattle you HOPE to own…and whether or not you have a loaded gun. The Toposa people are strong (in every sense of the word), innovative, and usually have a won- South Sudan derful sense of humor. South Sudan Background Our Missionaries South Sudan is slightly smaller than Gregory and Latoya , are our IPHC the state of Texas, with an estimated missionaries in South Sudan. Because Above: Greg and Latoya McClerkin, population of 12.8 million (compa- of the tough living conditions in this our Hope4Sudan missionaries, are a rable to Pennsylvania). It remains area, Latoya and the boys reside in blessing in South Sudan and Eldoret, the youngest nation in our world Kenya and come to South Sudan for Kenya. Their son Ethan is celebrat- since gaining its independence from holidays, special events, and whenever ing his 7th birthday along with little brother, Colton, who soon turns 2. Sudan in July 2011. Renewed conflict needed. Gregory also travels to Eldo- in December 2013 led to what the ret, Kenya, for Compass events and UN called “one of the world’s worst other business matters. That furlough humanitarian crises.” spanned several months of 2017 and The civil war in South Sudan caused the early part of 2018. widespread famine and encouraged Colton and his big brother Ethan more than two million people to flee, enjoy their home in Eldoret, Kenya, says economist.com. -

Final Resettlement Action Plan Report

Public Disclosure Authorized Upgrading of the NADAPAL-JUBA ROAD Public Disclosure Authorized from Gravel to Paved (Bitumen) Standards FINAL RESETTLEMENT ACTION PLAN REPORT Public Disclosure Authorized Issued on: November 6th, 2013 EMPLOYER: Ministry of Transport, Roads and Bridges, Government of Republic of South Sudan CONSULTANT: Public Disclosure Authorized SMEC INTERNATIONAL PTY LIMITED, AUSTRALIA REVISED BY: Ing. MRS. RITA OHENE SARFOH i | P a g e Table of Contents List of Tables ............................................................................................................................................. vi List of Figures ........................................................................................................................................ vi Acronyms ................................................................................................................................................. vii Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................... ix Chapter 1Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Background .................................................................................................................................. 1 1.2 The Statements of Objectives........................................................................................................ 2 1.3 Brief Description