Symptoms and Causes Insecurity and Underdevelopment in Eastern Equatoria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cholera in South Sudan Situation Report # 95 As at 23:59 Hours, 29 September to 5 October 2014

Republic of South Sudan Cholera in South Sudan Situation Report # 95 as at 23:59 Hours, 29 September to 5 October 2014 Situation Update As of 5 October 2014, a total of 6,139 cholera cases including 139 deaths (CFR 2%) had been reportedTable 1. Summary in South of Suda choleran as cases summarizedreported in in Juba Tables County 1 and, 23 2.April – 5 October 2014 New New New deaths Total cases Total Total admisions discharges Total Total cases Reporting Sites 29 Sept to currently facility community Total cases 29 Sept to 29 Sept to deaths discharged 5 Oct 2014 admitted deaths deaths 5 Oct 2014 5 Oct 2014 JTH CTC 0 0 0 0 16 0 16 1466 1482 Gurei CTC (changed to ORP) Closed 28 July 2 0 2 365 367 Tongping CTC 0 2 1 3 69 72 Closed August Jube 3/UN House CTC Closed August 0 0 0 0 97 97 Nyakuron West CTC Closed 15 July 0 0 0 18 18 Gumbo CTC Closed 5 July 0 0 0 48 48 Nyakuron ORP Closed 5 July 0 0 0 20 20 Munuki ORP Closed 5 July 0 0 0 8 8 Gumbo ORP Closed 15 July 0 3 3 67 70 Pager PHCU 0 0 0 0 1 5 6 42 48 Other sites 0 0 0 1 15 16 1 17 Total 0 0 0 0 22 24 46 2201 2247 N.B. To prevent double counting of patients, transferred cases from ORPs to CTCs are not counted in the ORPs. Table 2: Summary of cholera cases reported outside Juba County, 23 April – 5 October 2014 New New New Total cases Total Total admisions discharges deaths Total Total cases Total States Reporting Sites currently facility community 29 Sept to 29 Sept to 29 Sep to deaths discharged cases admitted deaths deaths 5 Oct 2014 5 Oct 2014 5 Oct 14 Kajo-Keji civil hospital 0 0 0 0 -

Figure 1. Southern Sudan's Protected Areas

United Nations Development Programme Country: Sudan PROJECT DOCUMENT Launching Protected Area Network Management and Building Capacity in Post-conflict Project Title: Southern Sudan By end of 2012, poverty especially among vulnerable groups is reduced and equitable UNDAF economic growth is increased through improvements in livelihoods, food security, decent Outcome(s): employment opportunities, sustainable natural resource management and self reliance; UNDP Strategic Plan Environment and Sustainable Development Primary Outcome: Catalyzing access to environmental finance UNDP Strategic Plan Secondary Outcome: Mainstreaming environment and energy Expected CP Outcome(s): Strengthened capacity of national, sub-national, state and local institutions and communities to manage the environment and natural disasters to reduce conflict over natural resources Expected CPAP Output(s) 1. National and sub-national, state and local institutions and communities capacities for effective environmental governance, natural resources management, conflict and disaster risk reduction enhanced. 2. Comprehensive strategic frameworks developed at national and sub-national levels regarding environment and natural resource management Executing Entity/Implementing Partner: NGO Execution Modality – WCS in cooperation with the Ministry of Wildlife Conservation and Tourism of the Government of Southern Sudan (MWCT-GoSS) Implementing Entity/Responsible Partners: United Nations Development Programme Brief Description The current situation Despite the 1983 to 2005 civil war, many areas of Southern Sudan still contain areas of globally significant habitats and wildlife populations. For example, Southern Sudan contains one of the largest untouched savannah and woodland ecosystems remaining in Africa as well as the Sudd, the largest wetland in Africa, of inestimable value to the flow of the River Nile, the protection of endemic species and support of local livelihoods. -

2019 Torit Multi-Sector Household Survey Report

2019 Torit Multi-Sector Household Survey Report February 2019 Contents RECENT OVERALL TRENDS and BASIC RECOMMENDATIONS ..................................................................... 4 BACKGROUND ............................................................................................................................................. 6 TORIT DASHBOARD ..................................................................................................................................... 7 COMMUNITY CONSOLE ............................................................................................................................ 10 I. PURPOSE, METHODOLOGY and SCOPE ............................................................................................. 11 PEOPLE WELFARE ...................................................................................................................................... 15 1. LIVELIHOOD ....................................................................................................................................... 15 2. MAIN PROBLEMS and RESILIENCE (COPING CAPACITY) ................................................................... 17 3. FOOD SECURITY................................................................................................................................. 19 4. HEALTH .............................................................................................................................................. 22 5. HYGIENE ........................................................................................................................................... -

Cholera Situation Analysis and Hotspot Mapping in South Sudan

GTFCC Meeting for the Working Groups on CHOLERA SITUATION ANALYSIS Surveillance AND HOTSPOT MAPPING IN (Epidemiology and Laboratory) (15th to 17th SOUTH SUDAN March 2019) BACKGROUN D 1. South Sudan borders Uganda, Kenya, Ethiopia, Sudan, DR Congo, & CAR 2. Got independence in 2011 3. Protracted Grade 3 crisis since 2013 (situation improving since Sept 2018) 4. Severe food insecurity – 7.1million (63% of population) – 45,000 faced with famine 5. 1.87 million IDPs & 2.27million refugees to neighboring countries 1. Multisectoral taskforce in place chaired by MoH with the other sectors (Water & COORDINATION OF Humanitarian Affairs) and partners (Health + WASH) CHOLERA CONTROL clusters as members 2. Draft National Cholera Control Plan pending WASH assessment & stakeholder review/costing 3. Implemented preventive OCV campaigns since 2017 (2.9 million doses approved 27/Mar/2019) 4. Sub-optimal involvement of other sectors and WASH in OCV preventive campaigns CHOLERA IN SOUTH 1. South Sudan endemic for SUDANcholera 2. Since the 2013 crisis onset – cholera outbreaks – 2014 - 2017 3. Between 2014-2017 at least 28,676 cases & 644 deaths reported 4. All outbreaks started in Juba 5. Cases reported along River Nile, cattle camps, IDPs, islands, & Commercial hubs 1600 Cholera cases in South Sudan, 2014 s e s a 1200 Cholera cases in South Sudan, 2014 s c e f s a o 2014 c f r 800 o 2014 e 1000 r e b b m 400 m CHOLERA IN u u N N 0 0 1 3 5 7 9 111315171921232527293133353739414345474951 1 3 5 7 9 111315171921232527293133353739414345474951 Week of onset Week of onset 1900 Cholera cases in South Sudan, 2015 s e s SOUTH a c 1600 Cholera cases in South Sudan, 2015 f o s r 900 e e 2015 b s m a 1200 u c N f o -100 r 800 1 3 5 7 9 111315171921232527293133353739414345474951 SUDAN e 2015 Week of onset b m 400 u Cholera cases in South Sudan, 2016 s N e 1600 s a 0 c f 1200 1. -

Humanitarian Response Plan South Sudan

HUMANITARIAN HUMANITARIAN PROGRAMME CYCLE 2021 RESPONSE PLAN ISSUED MARCH 2021 SOUTH SUDAN 01 About This document is consolidated by OCHA on behalf of the Humanitarian Country Team and partners. The Humanitarian Response Plan is a presentation of the coordinated, strategic response devised by humanitarian agencies in order to meet the acute needs of people affected by the crisis. It is based on, and responds to, evidence of needs described in the Humanitarian Needs Overview. Manyo Renk Renk SUDAN Kaka Melut Melut Maban Fashoda Riangnhom Bunj Oriny UPPER NILE Abyei region Pariang Panyikang Malakal Abiemnhom Tonga Malakal Baliet Aweil East Abiemnom Rubkona Aweil North Guit Baliet Dajo Gok-Machar War-Awar Twic Mayom Atar 2 Longochuk Bentiu Guit Mayom Old Fangak Aweil West Turalei Canal/Pigi Gogrial East Fangak Aweil Gogrial Luakpiny/Nasir Maiwut Aweil West UNITY Yomding Raja NORTHERN South Gogrial Koch Nyirol Nasir Maiwut Raja BAHR EL Bar Mayen Koch Ulang Kuajok WARRAP Leer Lunyaker Ayod GHAAL Tonj North Mayendit Ayod Aweil Centre Waat Mayendit Leer Uror Warrap Romic ETHIOPIA Yuai Tonj East WESTERN BAHR Nyal Duk Fadiat Akobo Wau Maper JONGLEI CENTRAL EL GHAAL Panyijiar Duk Akobo Kuajiena Rumbek North AFRICAN Wau Tonj Pochalla Jur River Cueibet REPUBLIC Tonj Rumbek Kongor Pochala South Cueibet Centre Yirol East Twic East Rumbek Adior Pibor Rumbek East Nagero Wullu Akot Yirol Bor South Tambura Yirol West Nagero LAKES Awerial Pibor Bor Boma Wulu Mvolo Awerial Mvolo Tambura Terekeka Kapoeta International boundary WESTERN Terekeka North Mundri -

Linkages-Success-Stories-South-Sudan

JULY 2016 SUCCESS STORY Success on Several Levels in South Sudan In South Sudan, obtaining HIV care and treatment is difficult for people living with HIV. Only 10 percent of those eligible are currently enrolled on antiretroviral therapy (ART). But for one key population — female sex workers (FSWs) — the barriers to comprehensive HIV care and treatment are particularly daunting. Many sex workers cannot afford to lose income while waiting for services at overburdened hospitals. And those who do seek care often find providers are reluctant to serve them because of the stigma associated with sex work. Recruiting and retaining FSWs and other key populations (KPs) into the HIV cascade of services is a complex issue that demands a response at many levels. In South Sudan, LINKAGES is helping to generate a demand for services, improve access to KP-friendly services, and create a policy environment that is more conducive to the health rights of key populations. GENERATING DEMAND FOR SERVICES The justified mistrust that FSWs have for the health care system keeps many from seeking the services they need. Peer education and outreach is a critical component of engaging KPs in the HIV cascade. LINKAGES South Sudan conducted a mapping exercise to identify hotspots (or key locations) where sex work takes place. From these locations, 65 FSWs were identified and trained as peer educators to lead participatory education sessions among their peers. The sessions are designed to motivate FSWs to adopt healthy behaviors and develop the skills to do so. The sessions cover topics like condom use, regular screening and treatment for sexually transmitted infections (STIs), periodic testing for HIV, and enrollment into care and treatment services for those living with HIV. -

Magwi County

Resettlement, Resource Conflicts, Livelihood Revival and Reintegration in South Sudan A study of the processes and institutional issues at the local level in Magwi County by N. Shanmugaratnam Noragric Department of International Environment and Development No. Report Noragric Studies 5 8 RESETTLEMENT, RESOURCE CONFLICTS, LIVELIHOOD REVIVAL AND REINTEGRATION IN SOUTH SUDAN A study of the processes and institutional issues at the local level in Magwi County By N. Shanmugaratnam Noragric Report No. 58 December 2010 Department of International Environment and Development Studies, Noragric Norwegian University of Life Sciences, UMB Noragric is the Department of International Environment and Development Studies at the Norwegian University of Life Sciences (UMB). Noragric’s activities include research, education and assignments, focusing particularly, but not exclusively, on developing countries and countries with economies in transition. Noragric Reports present findings from various studies and assignments, including programme appraisals and evaluations. This Noragric Report was commissioned by the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (Norad) under the framework agreement with UMB which is administrated by Noragric. Extracts from this publication may only be reproduced after prior consultation with the employer of the assignment (Norad) and with the consultant team leader (Noragric). The findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed in this publication are entirely those of the authors and cannot be attributed directly to the Department of International Environment and Development Studies (UMB/Noragric). Shanmugaratnam, N. Resettlement, resource conflicts, livelihood revival and reintegration in South Sudan: A study of the processes and institutional issues at the local level in Magwi County. Noragric Report No. 58 (December 2010) Department of International Environment and Development Studies, Noragric Norwegian University of Life Sciences (UMB) P.O. -

Crossing Lines: “Magnets” and Mobility Among Southern Sudanese

“Magnets” andMobilityamongSouthernSudanese Crossing Lines United States Agency for InternationalDevelopment Agency for United States Contract No. HNE-I-00-00-00038-00 BEPS Basic Education and Policy Support (BEPS) Activity CREATIVE ASSOCIATES INTERNATIONAL INC In collaboration with CARE, THE GEORGE WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY, AND GROUNDWORK Crossing Lines “Magnets” and Mobility among Southern Sudanese A final report of two assessment trips examining the impact and broader implications of a new teacher training center in the Kakuma refugee camps, Kenya Prepared by: Marc Sommers Youth at Risk Specialist, CARE Basic Education and Policy Support Activity (BEPS) CARE, Inc. 151 Ellis Street, NE Atlanta, GA 30303-2439 and Creative Associates International, Inc. 5301 Wisconsin Avenue, NW Suite 700 Washington, DC 20015 Prepared for: Basic Education and Policy Support (BEPS) Activity US Agency for International Development Contract No. HNE-I-00-00-00038-00 Creative Associates International, Inc., Prime Contractor Photo credit: Marc Sommers 2002 Crossing Lines: “Magnets” and Mobility among Southern Sudanese CONTENTS I. Introduction: Do Education Facilities Attract Displaced People? The Current Debate .........................................................................................................................1 II. Background: Why Study Teacher Training in Kakuma and Southern Sudan? ......... 3 III. Findings: Issues Related to Mobility in Southern Sudan........................................... 8 A. Institutions at Odds: Contrasting Perceptions........................................................ -

Mining in South Sudan: Opportunities and Risks for Local Communities

» REPORT JANUARY 2016 MINING IN SOUTH SUDAN: OPPORTUNITIES AND RISKS FOR LOCAL COMMUNITIES BASELINE ASSESSMENT OF SMALL-SCALE AND ARTISANAL GOLD MINING IN CENTRAL AND EASTERN EQUATORIA STATES, SOUTH SUDAN MINING IN SOUTH SUDAN FOREWORD We are delighted to present you the findings of an assessment conducted between February and May 2015 in two states of South Sudan. With this report, based on dozens of interviews, focus group discussions and community meetings, a multi-disciplinary team of civil society and government representatives from South Sudan are for the first time shedding light on the country’s artisanal and small-scale mining sector. The picture that emerges is a remarkable one: artisanal gold mining in South Sudan ‘employs’ more than 60,000 people and might indirectly benefit almost half a million people. The vast majority of those involved in artisanal mining are poor rural families for whom alluvial gold mining provides critical income to supplement their subsistence livelihood of farming and cattle rearing. Ostensibly to boost income for the cash-strapped government, artisanal mining was formalized under the Mining Act and subsequent Mineral Regulations. However, owing to inadequate information-sharing and a lack of government mining sector staff at local level, artisanal miners and local communities are not aware of these rules. In reality there is almost no official monitoring of artisanal or even small-scale mining activities. Despite the significant positive impact on rural families’ income, the current form of artisanal mining does have negative impacts on health, the environment and social practices. With most artisanal, small-scale and exploration mining taking place in rural areas with abundant small arms and limited presence of government security forces, disputes over land access and ownership exacerbate existing conflicts. -

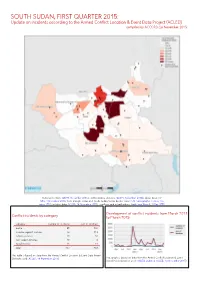

SOUTH SUDAN, FIRST QUARTER 2015: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 26 November 2015

SOUTH SUDAN, FIRST QUARTER 2015: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 26 November 2015 National borders: GADM, November 2015a; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015b; Abyei Area: SS- NBS, 1 December 2008; Ilemi triangle status and South Sudan/Sudan border status: UN Cartographic Section, Oc- tober 2011; incident data: ACLED, 14 November 2015; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 Development of conflict incidents from March 2013 Conflict incidents by category to March 2015 category number of incidents sum of fatalities battle 85 596 violence against civilians 52 113 remote violence 21 16 non-violent activities 18 2 riots/protests 16 11 total 192 738 This table is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (datasets used: ACLED, 14 November 2015). This graph is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (datasets used: ACLED, undated, ACLED, 14 November 2015). SOUTH SUDAN, FIRST QUARTER 2015: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 26 NOVEMBER 2015 LOCALIZATION OF CONFLICT INCIDENTS Note: The following list is an overview of the incident data included in the ACLED dataset. More details are available in the actual dataset (date, location data, event type, involved actors, information sources, etc.). In the following list, the names of event locations are taken from ACLED, while the administrative region names are taken from GADM data which serves as the basis for the map above. Data on incidents in the Abyei area are not reflected in this update. -

Water for Eastern Equatoria (W4EE)

Water for Eastern Equatoria (W4EE) he first integrated water resource management (IWRM) project of its kind in South Sudan, Water Water for Eastern for Eastern Equatoria (W4EE) was launched in Components 2013 as part of the broader bilateral water Tprogramme funded through the Dutch Multiannual Equatoria (W4EE) Strategic Plan for South Sudan (2012–2015). W4EE focuses on three interrelated From the very beginning, W4EE was planned as a pilot components: IWRM programme in the Torit and Kapoeta States of The role of integrated water resource manage- Eastern Equatoria focusing on holistic management of the ment in fostering resilience, delivering economic Kenneti catchment, conflict-sensitive oversight of water Component 1: Integrated water resource management of the development, improving health, and promoting for productive use such as livestock and farming, and Kenneti catchment and surrounds peace in a long-term process. improved access to safe drinking water as well as sanitati- on and hygiene. The goal has always been to replicate key Component 2: Conflict-sensitive management of water for learnings and best practice in other parts of South Sudan. productive use contributes to increased, sustained productivity, value addition in agriculture, horticulture, and livestock The Kenneti catchment is very important to the Eastern Equatoria region for economic, social, and biodiversity reasons. The river has hydropower potential, supports the Component 3: Safely managed and climate-resilient drinking livelihoods of thousands of households, and the surroun- water services and improved sanitation and hygiene are available, ding area hosts a national park with forests and wetlands operated and maintained in a sustainable manner. as well as wild animals and migratory birds. -

United Nations Nations Unies

United Nations Nations Unies Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs Humanitarian Coordinator in South Sudan condemns killing of an aid worker in Budi, Eastern Equatoria (Juba, 13 May 2021) The Humanitarian Coordinator in South Sudan, Alain Noudéhou, has condemned the killing of an aid worker in Budi, Eastern Equatoria, and called for authorities and communities to ensure that humanitarian personnel can move safely along roads and deliver assistance to the most vulnerable people. On 12 May, an aid worker was killed when criminals fired at a clearly marked humanitarian vehicle. The vehicle was part of a team of international non-governmental organizations and South Sudanese government health workers traveling to a health facility. The team was driving from Chukudum to Kapoeta in Budi County in an area that has seen several roadside ambushes this year. “I am shocked by this violent act and send my condolences to the family and colleagues of the deceased. The roads are a vital connection between humanitarian organizations and communities in need, and we must be able to move safely across the country without fear,” Mr. Noudéhou said and added: “I call on the Government to strengthen law enforcement along these roads.” This is the first aid worker killed in South Sudan in 2021. In 2020, nine aid workers were killed. *** Note to editors To learn more about humanitarian access in South Sudan, see the first quarterly access snapshot of 2021 here: https://bit.ly/3dZQtGw For further information, please contact: Emmi Antinoja, Head of Communications and Information Management, +211 92 129 6333 [email protected] Anthony Burke, Public Information Officer, +211 92 240 6014 and [email protected] OCHA press releases are available at www.unocha.org/south-sudan or www.reliefweb.int.