Dyron Daughrity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dravidian Languages

THE DRAVIDIAN LANGUAGES BHADRIRAJU KRISHNAMURTI The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 2RU, UK 40 West 20th Street, New York, NY 10011–4211, USA 477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, VIC 3207, Australia Ruiz de Alarc´on 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town 8001, South Africa http://www.cambridge.org C Bhadriraju Krishnamurti 2003 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2003 Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeface Times New Roman 9/13 pt System LATEX2ε [TB] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 0521 77111 0hardback CONTENTS List of illustrations page xi List of tables xii Preface xv Acknowledgements xviii Note on transliteration and symbols xx List of abbreviations xxiii 1 Introduction 1.1 The name Dravidian 1 1.2 Dravidians: prehistory and culture 2 1.3 The Dravidian languages as a family 16 1.4 Names of languages, geographical distribution and demographic details 19 1.5 Typological features of the Dravidian languages 27 1.6 Dravidian studies, past and present 30 1.7 Dravidian and Indo-Aryan 35 1.8 Affinity between Dravidian and languages outside India 43 2 Phonology: descriptive 2.1 Introduction 48 2.2 Vowels 49 2.3 Consonants 52 2.4 Suprasegmental features 58 2.5 Sandhi or morphophonemics 60 Appendix. Phonemic inventories of individual languages 61 3 The writing systems of the major literary languages 3.1 Origins 78 3.2 Telugu–Kannada. -

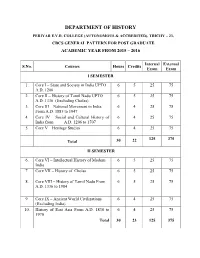

Department of History Periyar E.V.R

DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY PERIYAR E.V.R. COLLEGE (AUTONOMOUS & ACCREDITED), TRICHY – 23, CBCS GENERAL PATTERN FOR POST GRADUATE ACADEMIC YEAR FROM 2015 – 2016 Internal External S.No. Courses Hours Credits Exam Exam I SEMESTER 1. Core I – State and Society in India UPTO 6 5 25 75 A.D. 1206 2. Core II – History of Tamil Nadu UPTO 6 5 25 75 A.D. 1336 (Excluding Cholas) 3. Core III – National Movement in India 6 4 25 75 From A.D. 1885 to 1947 4. Core IV – Social and Cultural History of 6 4 25 75 India from A.D. 1206 to 1707 5. Core V – Heritage Studies 6 4 25 75 125 375 Total 30 22 II SEMESTER 6. Core VI – Intellectual History of Modern 6 5 25 75 India 7. Core VII – History of Cholas 6 5 25 75 8. Core VIII – History of Tamil Nadu From 6 5 25 75 A.D. 1336 to 1984 9. Core IX – Ancient World Civilizations 6 4 25 75 (Excluding India) 10. History of East Asia From A.D. 1830 to 6 4 25 75 1970 Total 30 23 125 375 III SEMESTER 11. Core XI – History of Political Thought 6 5 25 75 12. Core XII – Historiography 6 5 25 75 13. Core XIII – Socio - Economic and 6 5 25 75 Cultural History of India From A.D. 1707 to 1947 14. Core Based Elective - I: Contemporary 6 4 25 75 Issues in India 15. Core Based Elective - II: Dravidian 6 4 25 75 Movement Total 30 23 125 375 IV SEMESTER 16. -

Carey, H. (2020). Babylon, the Bible and the Australian Aborigines. in G

Carey, H. (2020). Babylon, the Bible and the Australian Aborigines. In G. Atkins, S. Das, & B. Murray (Eds.), Chosen Peoples: The Bible, Race, and Nation in the Long Nineteenth Century (pp. 55-72). (Studies in Imperialism). Manchester University Press. Peer reviewed version Link to publication record in Explore Bristol Research PDF-document This is the author accepted manuscript (AAM). The final published version (version of record) is available online via Manchester University Press at https://manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk/9781526143068/ . Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher University of Bristol - Explore Bristol Research General rights This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the reference above. Full terms of use are available: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/red/research-policy/pure/user-guides/ebr-terms/ Part I: Peoples and Lands Babylon, the Bible and the Australian Aborigines Hilary M. Carey [God] hath made of one blood all nations of men for to dwell on all the face of the earth, and hath determined the times before appointed, and the bounds of their habitation (Acts 17:26. KJV) 'One Blood': John Fraser and the Origins of the Aborigines In 1892 Dr John Fraser (1834-1904), a schoolteacher from Maitland, New South Wales, published An Australian Language, a work commissioned by the government of New South Wales for display in Chicago at the World's Columbian Exposition (1893). 1 Fraser's edition was just one of a range of exhibits selected to represent the products, industries and native cultures of the colony to the eyes of the world.2 But it was much more than a showpiece or a simple re-printing of the collected works of Lancelot Threlkeld (1788-1859), the 1 John Fraser, ed. -

Black Europeans, the Indian Coolies and Empire: Colonialisation and Christianized Indians in Colonial Malaya & Singapore, C

Black Europeans, the Indian Coolies and Empire: Colonialisation and Christianized Indians in Colonial Malaya & Singapore, c. 1870s - c. 1950s By Marc Rerceretnam A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of Sydney. February, 2002. Declaration This thesis is based on my own research. The work of others is acknowledged. Marc Rerceretnam Acknowledgements This thesis is primarily a result of the kindness and cooperation extended to the author during the course of research. I would like to convey my thanks to Mr. Ernest Lau (Methodist Church of Singapore), Rev. Fr. Aloysius Doraisamy (Church of Our Lady of Lourdes, Singapore), Fr. Devadasan Madalamuthu (Church of St. Francis Xavier, Melaka), Fr. Clement Pereira (Church of St. Francis Xavier, Penang), the Bukit Rotan Methodist Church (Kuala Selangor), the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies (Singapore), National Archives of Singapore, Southeast Asia Room (National Library of Singapore), Catholic Research Centre (Kuala Lumpur), Suara Rakyat Malaysia (SUARAM), Mr. Clement Liew Wei Chang, Brother Oliver Rodgers (De Lasalle Provincialate, Petaling Jaya), Mr. P. Sakthivel (Seminari Theoloji Malaysia, Petaling Jaya), Ms. Jacintha Stephens, Assoc. Prof. J. R. Daniel, the late Fr. Louis Guittat (MEP), my supervisors Assoc. Prof. F. Ben Tipton and Dr. Lily Rahim, and the late Prof. Emeritus S. Arasaratnam. I would also like to convey a special thank you to my aunt Clarice and and her husband Alec, sister Caryn, my parents, aunts, uncles and friends (Eli , Hai Long, Maura and Tian) in Singapore, Kuala Lumpur and Penang, who kindly took me in as an unpaying lodger. -

The Veiled Mother?

American Journal of Engineering Research (AJER) 2014 American Journal of Engineering Research (AJER) e-ISSN : 2320-0847 p-ISSN : 2320-0936 Volume-03, Issue-12, pp-23-33 www.ajer.org Research Paper Open Access THE SOUL OF THOLKAPPIAM (A New theory on “VALLUVAM”) M.Arulmani, V.R.Hema Latha, B.E. M.A., M.Sc., M.Phil. (Engineer) (Biologist) 1. Abstract: “THOLKAPPIAR” is a Great philosopher?... No….. No…. No…. ”AKATHIAR” shall be considered as a Great philosopher. “THOLKAPPIAR” shall be called as great ”POET” (Kaviperarasu) elaborating various Predefined ancient philosophies in his poems written in high grammatical form during post Vedic period. This scientific research focus that the population of “AKATHIAR” race (also called as Akkanna population) shall be considered as Ancient population lived in “KACHCHA THEEVU” during pre-vedic period (Say 5,00,000years ago) who written many philosophy of planet system, medicines Ethics in “PALM LEAF MANUSCRIPT”. It is further focused that the philosophy related to various subjects shall be considered derived from “stone culvert” (Tablet) scatterly available here and there. Alternatively it shall be stipulated that “Akathiar race” consider simply “TRANSLATING” the matter available in the Prehistoric stone culvert and wrote in the form of „palm leaf manuscript‟. It is speculated that the human ancestor populations shall be considered lived in „WHITE PLANET‟ (white mars) in the early universe who were expert in various field like Astrophysics, Astronomy, Medicines, Ethics, etc. written in single alphabet script called “TRIPHTHONG SCRIPT” written in a super solid stone matter. In proto Indo Europe language the Triphthong script shall be called as “VALLUVAM”. -

Social Sciences a Journal of ICFAI University, Nagaland

IUN Journal of Social Sciences A journal of ICFAI University, Nagaland Heritage Publishing House Near DABA, Duncan, Dimapur - 797113 Nagaland : India - i - Copyright© : ICFAI University, 2017 All right reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the permission of the copyright owner. Vol. II, Issue No. 2 Jan’ - June 2017 The views and opinions expressed in the journal are those of the individual author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of ICFAI University Nagaland ISSN 2395 - 3128 ` 200/- - ii - EDITORIAL BOARD EDITOR- IN-CHIEF Resenmenla Longchar, Ph.D ICFAI University Nagaland EDITORIAL ADVISORY MEMBERS VRK Prasad, Ph.D Former Vice Chancellor, ICFAI University Nagaland Prof. Moses M. Naga North Eastern Hill University, Shillong Jyoti Roy, Ph.D Patkai Christian College (Autonomous), Nagaland M.N.Rajesh, Ph.D University of Hyderabad, Hyderabad Saji Varghese, Ph.D Lady Keane College, Shillong G. N. Bag, Ph.D Former Associate Professor of Economics, KITT University, Odissa Vulli Dhanaraju, Ph.D Assam University, Diphu Campus Prof. Charles P. Alexander Vice Chancellor, ICFAI University Nagaland Kevizonuo Kuolie, Ph.D ICFAI University Nagaland Azono Khatso, ICFAI University Nagaland Kaini Lokho, ICFAI University Nagaland Temsurenla Ozükum, ICFAI University Nagaland - iii - CONTENTS Vol. II, Issue No. 2 Jan’ - June 2017 Editorial v Articles: Status of Karbi Women 1-9 - Maggie Katharpi United Nations Organization’s (UNO) Policy Initiatives on Ageing: A Review 10- 20 - Joseph Alugula Predicament in Understanding the Human Biology and Cognitive System 21-29 - Charles P. -

Caste, Culture and Conversion from the Perspective of an Indian Christian Family Based in Madras 1863-1906

Caste, Culture and Conversion from the Perspective of an Indian Christian Family based in Madras 1863-1906 Eleanor Jackson Senior Lecturer in Religious Studies, University of Derby [email protected] Based on a paper originally presented to Christian Missions in Asia: Third Annual Colloquium ‘Caste, Culture and Conversion in India Since 1793’ at the University of Derby, in association with the Department of History, University of Liverpool, and the Centre for Korean Studies, University of Sheffield (14-15 July, 1999). __________ Krupabai Satthianadhan, in her first novel, Kamala, A Story of Hindu Life (1894) describes how her heroine, only child of a Brahman sannayasi and recluse and a runaway Brahman heiress, gradually realises that the sudra girls minding the cattle on the mountainside where she grows up are different from her, and yet as she treats them kindly, they can all play together and help each other.(1) A very different world confronts her when she goes as a child bride to the Brahman quarter of the local town. In fact the novel turns around the conversations she and the other unhappy girls have around the Brahmans' well. Temple festivals and pilgrimages provide the only escape, until her cousin Ramchander acquaints her with her true circumstances following her father's death, her estranged husband dies shortly after her infant daughter's death, and she can devote herself to 'unselfish works of charity'.(2) There is more than an echo of George Eliot in the story, not surprisingly since Krupabai studied and admired her works, including, presumably, Middlemarch. She also writes from the perspective of a teenage idealist who, like Krupabai herself, is intensely patriotic but achieves far more, in practical terms, than Dorothea Brooke. -

A Comparative Grammar of the Dravidian Languages

World Classical Tamil Conference- June 2010 51 A COMPARATIVE GRAMMAR OF THE DRAVIDIAN LANGUAGES Rt. Rev. R.Caldwell * Rev. Caldwell's Comparative Grammar is based on four decades of his deep study and research on the Dravidian languages. He observes that Tamil language contains a common repository of Dravidian forms and roots. His prefatory note to his voluminous work is reproduced here. Preface to the Second Edition It is now nearly nineteen years since the first edition of this book was published, and a second edition ought to have appeared long ere this. The first edition was, soon exhausted, and the desirableness of bringing out a second edition was often suggested to me. But as the book was a first attempt in a new field of research and necessarily very imperfect, I could not bring myself to allow a second edition to appear without a thorough revision. It was evident, however, that the preparation of a thoroughly revised edition, with the addition of new matter wherever it seemed to be necessary, would entail upon me more labour than I was likely for a long time to be able to undertake. .The duties devolving upon me in India left me very little leisure for extraneous work, and the exhaustion arising from long residence in a tropical climate left me very little surplus strength. For eleven years, in addition to my other duties, I took part in the Revision of the Tamil Bible, and after that great work had come to. an end, it fell to my lot to take part for one year more in the Revision of the Tamil Book of, * Source: A Comparative Grammar of the Dravidian or South-Indian Family of Languages , Rt.Rev. -

Directorate of School Education, Puducherry

HISTORY I. CHOOSE THE CORRECT ANSWER UNIT - 1: OUTBREAK OF WORLD WAR I AND ITS AFTERMATH 1. What were the three major empires shattered by the end of First World War? Germany, Austria- Hungary and the Ottomans 2. Where did the Ethiopian army defeat the Italian army? Adowa 3. Which country emerged as the strongest in East Asia towards the close of nineteenth century? Japan 4. Who said “imperialism is the highest stage of capitalism”? Lenin ** 5. What is the Battle of Marne remembered for? Trench Warfare ** 6. Which country after the World War I took to policy of Isolation? USA ** 7. To which country the first Secretary General of League of Nations belonged? Britain 8. Which country was expelled from the League of Nations for attacking Finland? Russia Unit - 2 : THE WORLD BETWEEN TWO WORLD WARS 1. With whom of the following was the Lateran Treaty signed by Italy? Pope ** 2. With whose conquest the Mexican civilization collapsed? HernanPUDUCHERRY Cortes 3. Who made Peru as part of their dominions? Spaniards 4. Which President of the USA pursued “Good Neighbour” policy towards Latin America? Roosevelt ** 5. Which part of the World disliked dollar Imperialism? Latin America 6. Who was the brain behind the apartheid policy in South Africa?2019-20 Smuts ** 7. Which quickened the process of liberation in LatinEDUCATION, America? Napoleonic Invasion 8. Name the President who made amendment to MonroeNOKKI doctrine to justify American intervention in the affairs of Latin America. Theodore Roosevelt ** SCHOOL Unit – 3 : WORLD WAR II OF 1. When did the Japanese formally sign of their surrender? 2 September, 1945 2. -

1237-1242 Research Article Christian Contribution

Turkish Journal of Computer and Mathematics Education Vol.12 No.9 (2021),1237-1242 Research Article Christian Contribution To Tamil Literature Dr.M.MAARAVARMAN1 Assistant Professor in History,P.G&Research Department of History,PresidencyCollege, (Autonomous),Chennai-5. Article History: Received: 10 January 2021; Revised: 12 February 2021; Accepted: 27 March 2021; Published online: 20 April 2021 Abstract: The Christian missionaries studied Tamil language in order to propagate their religion. Henrique Henrique’s, Nobili, G.U. Pope, Constantine Joseph Beschi, Robert Caldwell, Barthalomaus Zieganbalg, Francis Whyte Ellis, Samuel Vedanayagam Pillai, Henry Arthur Krishna Pillai, Vedanayagam Sastriyar, Abraham Pandithar had been the Christian campaigners and missionaries. Pope was along with Joseph Constantius Beschi, Francis Whyte Ellis, and Bishop Robert Caldwell one of the major scholars on Tamil. Ziegenbalg wrote a number of texts in Tamil he started translating the New Testament in 1708 and completed in 1711.They performed a remarkable position to the improvement of Tamil inclusive of the introduction of Prose writing.Christian Priest understood the need to learn the neighborhood language for effective evangelization. Moreover, they centered on Tamil literature in order to recognize the cultural heritage and spiritual traditions. The Priest learnt Tamil language and literature with an agenda and no longer out of love or passion or with an intention of contributing to the growth of the language.Tamil Christian Literature refers to the various epic, poems and other literary works based on the ethics, customs and principles of Christian religion. Christians both the catholic and Protestant missionaries have also birthed literary works. Tamil- Christian works have enriched the language and its literature. -

History Research Journal ISSN: 0976-5425 Vol-5-Issue-4-September-October 2019

History Research Journal ISSN: 0976-5425 Vol-5-Issue-4-September-October 2019 SOCIAL SERVICES OF ROBERT CALDWELL Dr. R. SUJI PRABHA, Assistant Professor of History, Women’s Christian College, Nagercoil -1. ABSTRACT “Excelling as a scholar and philologist intimately acquainted with the Tamil people, their history, language and customs and elegant writer. He attained a wide reputation, bringing honour thereby to the missionary’s calling and strengthening the cause of missions in the church at home. But all his attainments and fame did not divert him from his great purpose and the simplicity of his missionary life. He trained many native agents, brought thousands of heathen in to the church of Christ, raised the character and status not of the Christians only and won their attachment and reverence.” INTRODUCTION Robert Caldwell was one of the renowned scholar and important Missionaries of South India. He was not only a religious priest, but also a multilinguist, historian, and a social scientist. He knows eighteen languages including Greek, Latin, Hebrew, English, Irish, Scottish, Tamil, Telugu, Kannada, Sanskrit and Malayalam. In his own words “I was born in Ireland, educated in Scotland, enlisted myself in London Mission Society. He lived in India for a pretty long time and indulged in Indian life style, and became one among the Indians”. Caldwell was born at Ireland on 7th of May 1814 to poor Scottish Presbyterian parents. His family on returning to Scotland took up their abode in Glasgow. So, he inculcated the habit of reading books and not scriptural books. His acquaintance with the priests made him think of God and thereby he committed himself to the Lord in 1830 at the age of sixteen. -

Bio-Linguistic Studies on the South Indian Dravidian Language Family

ISSN (Online) 2393-8021 IARJSET ISSN (Print) 2394-1588 International Advanced Research Journal in Science, Engineering and Technology Vol. 6, Issue 12, December 2019 Bio-Linguistic Studies on the South Indian Dravidian Language Family and Population Radhika Bhat1, Anoop Markande2* Assistant Professor, Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, Indukaka Ipkowala Institute of Management, Charotar University of Science and Technology (CHARUSAT), Changa, Gujjarat 388421, India1 Assistant Professor, Department of Biological Sciences, PD Patel Institute of Applied Sciences, Charotar University of Science and Technology (CHARUSAT), Changa, Gujarat 388421, India2 Abstract: The Dravidian language family of South India is considered to be one of the most prominent connected language family known with 73 major sections and subsections. The Dravidian language diversification starts at a point where the proto-Dravidian language started split coinciding with the decline of the Indus valley civilization around 1500 years ago. This era also coincides with the enhanced diversification of Sanskrit to different Prakrit languages within Indian subcontinent. The next significant change in the Dravidian languages occurs during the conquest of Alexander coinciding with the beginning of Proto-Telugu and proto-Kannada. This era coincided with the emergence and popularisation of Buddhism and Jainism (social Renaissance), the diversification of the languages also can be traced with the mixing of the population during these periods. These have been traced using mtDNA and Y-chromosomal studies. The changes in the genetic makeup which could be traced along the migratory route to Australia can be easily ascertained. Thus, the genetic divergence of human populations within this area could be correlated with the diversification of the language family due to various factors.