A Comparative Grammar of the Dravidian Languages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Spread of Sanskrit* (Published In: from Turfan to Ajanta

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Serveur académique lausannois Spread of Sanskrit 1 Johannes Bronkhorst Section de langues et civilisations orientales Université de Lausanne Anthropole CH-1009 Lausanne The spread of Sanskrit* (published in: From Turfan to Ajanta. Festschrift for Dieter Schlingloff on the Occasion of his Eightieth Birthday. Ed. Eli Franco and Monika Zin. Lumbini International Research Institute. 2010. Vol. 1. Pp. 117-139.) A recent publication — Nicholas Ostler’s Empires of the Word (2005) — presents itself in its subtitle as A Language History of the World. Understandably, it deals extensively with what it calls “world languages”, languages which play or have played important roles in world history. An introductory chapter addresses, already in its title, the question “what it takes to be a world language”. The title also provides a provisional answer, viz. “you never can tell”, but the discussion goes beyond mere despair. It opposes the “pernicious belief” which finds expression in a quote from J. R. Firth, a leading British linguist of the mid-twentieth century (p. 20): “World powers make world languages [...] Men who have strong feelings directed towards the world and its affairs have done most. What the humble prophets of linguistic unity would have done without Hebrew, Arabic, Latin, Sanskrit and English, it it difficult to imagine. Statesmen, soldiers, sailors, and missionaries, men of action, men of strong feelings have made world languages. They are built on blood, money, sinews, and suffering in the pursuit of power.” Ostler is of the opinion that this belief does not stand up to criticism: “As soon as the careers of languages are seriously studied — even the ‘Hebrew, Arabic, Latin, Sanskrit and English’ that Firth explicitly mentions as examples — it becomes clear that this self-indulgently tough-minded view is no guide at all to what really makes a language capable of spreading.” He continues on the following page (p. -

CONTENT K to 8

CONTENT K to 8 HINDI 28. Saraswati Sanskrit Manjusha ........................ 22 (ICSE) 1. Nai Rangoli ................................................... 7 29. Saraswati Sanskrit Sudha ................... 23 (ICSE) 2. Rangoli Varnamala........................................ 8 30. Saraswati Deep Manika ..................... 24 31. Saraswati Sanskrit Manjusha (ICSE) ............. 25 3. Rangoli Sulekh Abhyas ................................ 8 32. Saraswati Sanskrit Vyakaran ......................... 26 4. Saraswati Sarika ............................................ 9 33. Saraswati Sanskrit Vyakaran Sudha .............. 26 5. Kalptaru ........................................................ 9 34. Saraswati Manika Sanskrit 6. Naveen Sankalp ............................................ 10 Vyakaran (REVISED) ..................................... 27 7. Sargam .......................................................... 11 35. Saraswati Ruchira Abhyas Pustika .............. 27 8. Nai Swati ...................................................... 12 9. Elementary Hindi Reader ............................. 12 URDU 10. Saras Hindi Pathmala (NEW) ....................... 13 36. Bazeecha ....................................................... 28 11. Saraswati Nai Sarika (ICSE) ........................ 13 PRE-SCHOOL 12. Rangoli (ICSE) .............................................. 14 37. Tippy Tippy Tap ............................................ 29 13. Sankalp Hindi Pathmala (ICSE) .................... 15 38. Junior Smart Kit ........................................... -

The Dravidian Languages

THE DRAVIDIAN LANGUAGES BHADRIRAJU KRISHNAMURTI The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 2RU, UK 40 West 20th Street, New York, NY 10011–4211, USA 477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, VIC 3207, Australia Ruiz de Alarc´on 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town 8001, South Africa http://www.cambridge.org C Bhadriraju Krishnamurti 2003 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2003 Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeface Times New Roman 9/13 pt System LATEX2ε [TB] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 0521 77111 0hardback CONTENTS List of illustrations page xi List of tables xii Preface xv Acknowledgements xviii Note on transliteration and symbols xx List of abbreviations xxiii 1 Introduction 1.1 The name Dravidian 1 1.2 Dravidians: prehistory and culture 2 1.3 The Dravidian languages as a family 16 1.4 Names of languages, geographical distribution and demographic details 19 1.5 Typological features of the Dravidian languages 27 1.6 Dravidian studies, past and present 30 1.7 Dravidian and Indo-Aryan 35 1.8 Affinity between Dravidian and languages outside India 43 2 Phonology: descriptive 2.1 Introduction 48 2.2 Vowels 49 2.3 Consonants 52 2.4 Suprasegmental features 58 2.5 Sandhi or morphophonemics 60 Appendix. Phonemic inventories of individual languages 61 3 The writing systems of the major literary languages 3.1 Origins 78 3.2 Telugu–Kannada. -

Dyron Daughrity

Hinduisms, Christian Missions, and the Tinnevelly Shanars: th A Study of Colonial Missions in 19 Century India DYRON B. DAUGHRITY, PHD Written During 5th Year, PhD Religious Studies University of Calgary Calgary, Alberta Protestant Christian missionaries first arrived in south India in 1706 when two young Germans began their work at a Danish colony on India's southeastern coast known as Tranquebar. These early missionaries, Bartholomaeus Ziegenbalg and Heinrich Pluetschau, brought with them a form of Lutheranism that emphasized personal piety and evangelistic fervour. They had little knowledge of what to expect from the peoples they were about to encounter. They were entering a foreign culture with scarcely sufficient preparation, but with the optimistic view that they would succeed in their task of bringing Christianity to the land of the “Hindoos.”1 The missionaries continued to come and by 1801, when the entire district of Tinnevelly (in south India) had been ceded to the British, there were pockets of Protestant Christianity all over the region. For the missionaries, the ultimate goal was conversion of the “heathen.” Vast resources were contributed by various missionary societies in Europe and America in order to establish churches, 1 In 2000, an important work by D. Dennis Hudson entitled Protestant Origins in India: Tamil Evangelical Christians, 1706-1835 (Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 2000) brought to light this complex and fascinating story of these early missionaries encountering for the first time an entirely new culture, language, and religion. This story sheds significant insight on the relationship between India and the West, particularly regarding religion and culture, and serves as a backdrop for the present research. -

GRAMMAR of OLD TAMIL for STUDENTS 1 St Edition Eva Wilden

GRAMMAR OF OLD TAMIL FOR STUDENTS 1 st Edition Eva Wilden To cite this version: Eva Wilden. GRAMMAR OF OLD TAMIL FOR STUDENTS 1 st Edition. Eva Wilden. Institut français de Pondichéry; École française d’Extrême-Orient, 137, 2018, Collection Indologie. halshs- 01892342v2 HAL Id: halshs-01892342 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01892342v2 Submitted on 24 Jan 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. GRAMMAR OF OLD TAMIL FOR STUDENTS 1st Edition L’Institut Français de Pondichéry (IFP), UMIFRE 21 CNRS-MAE, est un établissement à autonomie financière sous la double tutelle du Ministère des Affaires Etrangères (MAE) et du Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS). Il est partie intégrante du réseau des 27 centres de recherche de ce Ministère. Avec le Centre de Sciences Humaines (CSH) à New Delhi, il forme l’USR 3330 du CNRS « Savoirs et Mondes Indiens ». Il remplit des missions de recherche, d’expertise et de formation en Sciences Humaines et Sociales et en Écologie dans le Sud et le Sud- est asiatiques. Il s’intéresse particulièrement aux savoirs et patrimoines culturels indiens (langue et littérature sanskrites, histoire des religions, études tamoules…), aux dynamiques sociales contemporaines, et aux ecosystèmes naturels de l’Inde du Sud. -

Bulletin of the Indus Research Centre

Bulletin of the Indus Research Centre ROJA MUTHIAH RESEARCH LIBRARY No. 3 | December 2012 BULLETIN OF THE INDUS RESEARCH CENTRE No. 3, December 2012 Indus Research Centre Roja Muthiah Research Library Chennai, India The ‘High-West: Low-East’ Dichotomy of Indus Cities: A Dravidian Paradigm R. Balakrishnan Indus Research Centre Roja Muthiah Research Library © Indus Research Centre, Roja Muthiah Research Library, December 2012 Acknowledgements I thankfully acknowledge the assistance given by Subhadarshi Mishra, Ashok Dakua and Abhas Supakar of SPARC Bhubaneswar, Lazar Arockiasamy, Senior Geographer, DCO Chennai, in GIS related works. Title page illustration: Indus Seal (Marshal. 338) (Courtesy: Corpus of Indus Seals and Inscriptions, Vol.1) C O N T E N T S Abstract 01 Introduction 02 Part 1 Dichotomous Layouts of the Indus Cities 05 Part II The ‘High-West: Low-East’ Framework in Dravidian Languages 18 Part III Derivational History of Terms for Cardinal Directions in Indo- 30 European Languages Part IV Human Geographies: Where ‘High’ is ‘West’ and ‘Low’ is ‘East’ 34 Part V The Toponomy of Hill Settlements 37 Part VI The Toponomy of ‘Fort’ Settlements 44 Part VII The Comparative Frameworks of Indus, Dravidian and Indo- 46 Aryan Part VIII The Lingering Legacy 49 Part IX Conclusions 53 Note on GIS 54 Annexure I 55 Annexure II 58 Annexure III 66 References 67 A b b r e v i a t i o n s General DEMS = Direction-Elevation-Material-Social; GIS = Geographical Information System; Lat./ N = Latitude/North; Long./ E = Longitude/East; MSL = Mean Sea Level Languages Ass = Assamese; Beng = Bengali; Br = Brahui; Ga = Gadaba; Go = Gondi; Guj = Gujarati; H = Hindi; Ka = Kannada; Kas = Kashmiri; Ko = Kota; Kod = Kodagu; Kol = Kolami; Kur = Kuruk; Ma = Malayalam; Mar = Marathi; Or = Oriya; Pa = Parji; Panj = Punjabi; Pkt = Prakrit; Sgh = Singhalese; Skt = Sanskrit; Ta. -

A Dependency Treebank for Telugu Taraka Rama University of Oslo

English Conference Papers, Posters and Proceedings English 1-2018 A Dependency Treebank for Telugu Taraka Rama University of Oslo Sowmya Vajjala Iowa State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/engl_conf Part of the Communication Technology and New Media Commons Recommended Citation Rama, Taraka and Vajjala, Sowmya, "A Dependency Treebank for Telugu" (2018). English Conference Papers, Posters and Proceedings. 8. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/engl_conf/8 This Conference Proceeding is brought to you for free and open access by the English at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Conference Papers, Posters and Proceedings by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Dependency Treebank for Telugu Abstract In this paper, we describe the annotation and development of Telugu treebank following the Universal Dependencies framework. We manually annotated 1328 sentences from a Telugu grammar textbook and the treebank is freely available from Universal Dependencies version 2.1.1 In this paper, we discuss some language specific nnota ation issues and decisions; and report preliminary experiments with POS tagging and dependency parsing. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first freely accessible and open dependency treebank for Telugu. Keywords Telugu, Universal dependencies, adverbial clauses, relative clauses Disciplines Communication Technology and New Media Comments The following proceeding is published as Proceedings of the 16th International Workshop on Treebanks and Linguistic Theories (TLT16), pages 119–128, Prague, Czech Republic, January 23–24, 2018. Distributed under a CC-BY 4.0 licence. -

Identity and Language of Tamil Community in Malaysia: Issues and Challenges

DOI: 10.7763/IPEDR. 2012. V48. 17 Identity and Language of Tamil Community in Malaysia: Issues and Challenges + + + M. Rajantheran1 , Balakrishnan Muniapan2 and G. Manickam Govindaraju3 1Indian Studies Department, University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia 2Swinburne University of Technology, Sarawak, Malaysia 3School of Communication, Taylor’s University, Subang Jaya, Malaysia Abstract. Malaysia’s ruling party came under scrutiny in the 2008 general election for the inability to resolve pressing issues confronted by the minority Malaysian Indian community. Some of the issues include unequal distribution of income, religion, education as well as unequal job opportunity. The ruling party’s affirmation came under critical situation again when the ruling government decided against recognising Tamil language as a subject for the major examination (SPM) in Malaysia. This move drew dissatisfaction among Indians, especially the Tamil community because it is considered as a move to destroy the identity of Tamils. Utilising social theory, this paper looks into the fundamentals of the language and the repercussion of this move by Malaysian government and the effect to the Malaysian Indians identity. Keywords: Identity, Tamil, Education, Marginalisation. 1. Introduction Concepts of identity and community had been long debated in the arena of sociology, anthropology and social philosophy. Every community has distinctive identities that are based upon values, attitudes, beliefs and norms. All identities emerge within a system of social relations and representations (Guibernau, 2007). Identity of a community is largely related to the race it represents. Race matters because it is one of the ways to distinguish and segregate people besides being a heated political matter (Higginbotham, 2006). -

Common Spoken Tamil Made Easy

COMMON SPOKEN TAMIL MADE EASY Third Edition by T. V. ADIKESAVALU Digital Version CHRISTIAN MEDICAL COLLEGE VELLORE Adi’s Book. COMMON SPOKEN TAMIL MADE EASY Third Edition by T. V. ADIKESAVALU Digital Version 2007 This book was prepared for the staff and students of Christian Medical College Vellore, for use in the Tamil Study Programme. No part may be reproduced without permission of the General Superintendent. 2 Adi’s Book. CONTENTS FOREWORD. 6 PREFACE TO SECOND EDITION. 7 THIRD EDITION: UPDATE. 8 I. NOTES FOR PRONUNCIATION & KEY FOR ABBREVIATIONS. 9 II. GRAMMAR LESSONS: Lesson No. Page. 1. Greetings and Forms of Address. 10 2. Pronouns, Interrogative and Demonstrative. 12 3. Pronouns, Personal. 15 4. The Verb ‘to be’, implied. 17 5. Cardinal Numbers 1 to 10, and Verbs - introduction. 19 6. Verbs - Positive Imperatives. 21 7. Verbs - Negative Imperatives, Weak & Strong Verbs, & Medials. 23 8. Nouns - forming the plural. 28 9. Nouns and Personal Pronouns - Accusative (Object) case. 30 10. Nouns and Personal Pronouns - Genitive (Possessive) Case. 34 11. Review, (Revision) No.I. 38 12. Verbs - Infinitives. 40 13. Nouns and Personal Pronouns, Dative Case, ‘to’ or ‘for’ & Verbs - Defective. 43 14. Verbs - defective (continued). 47 15. Cardinal Numbers 11 to 1000 & Time. 50 16. Verbs - Present tense, Positive. 54 17. Adjectives and Adverbs. 58 18. Post-Positions. 61 19. Nouns - Locative Case, 'at' or 'in'. 64 20. Post positions, (Continued). 67 21. Verbs - Future Tense, Positive, and Ordinal Numbers. 70 3 Adi’s Book. 22. Verbs - Present and Past, Negative, Page. and Potential Form to express 'may' 75 23. -

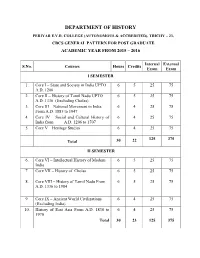

Department of History Periyar E.V.R

DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY PERIYAR E.V.R. COLLEGE (AUTONOMOUS & ACCREDITED), TRICHY – 23, CBCS GENERAL PATTERN FOR POST GRADUATE ACADEMIC YEAR FROM 2015 – 2016 Internal External S.No. Courses Hours Credits Exam Exam I SEMESTER 1. Core I – State and Society in India UPTO 6 5 25 75 A.D. 1206 2. Core II – History of Tamil Nadu UPTO 6 5 25 75 A.D. 1336 (Excluding Cholas) 3. Core III – National Movement in India 6 4 25 75 From A.D. 1885 to 1947 4. Core IV – Social and Cultural History of 6 4 25 75 India from A.D. 1206 to 1707 5. Core V – Heritage Studies 6 4 25 75 125 375 Total 30 22 II SEMESTER 6. Core VI – Intellectual History of Modern 6 5 25 75 India 7. Core VII – History of Cholas 6 5 25 75 8. Core VIII – History of Tamil Nadu From 6 5 25 75 A.D. 1336 to 1984 9. Core IX – Ancient World Civilizations 6 4 25 75 (Excluding India) 10. History of East Asia From A.D. 1830 to 6 4 25 75 1970 Total 30 23 125 375 III SEMESTER 11. Core XI – History of Political Thought 6 5 25 75 12. Core XII – Historiography 6 5 25 75 13. Core XIII – Socio - Economic and 6 5 25 75 Cultural History of India From A.D. 1707 to 1947 14. Core Based Elective - I: Contemporary 6 4 25 75 Issues in India 15. Core Based Elective - II: Dravidian 6 4 25 75 Movement Total 30 23 125 375 IV SEMESTER 16. -

A Study on Divergence in Malayalam and Tamil Language in Machine Translation Perceptive

A Study on Divergence in Malayalam and Tamil Language in Machine Translation Perceptive Jisha P Jayan Elizabeth Sherly Virtual Resource Centre for Virtual Resource Centre for Language Computing Language Computing IIITM-K,Trivandrum IIITM-K,Trivandrum [email protected] [email protected] Abstract others are specific with respect to the language pair (Lavanya et al., 2005; Saboor and Khan, Machine Translation has made significant 2010). Hence, the divergence in the translation achievements for the past decades. How- need to be studied both perspectives that is across ever, in many languages, the complex- the languages and language specific pair (Sinha, ity with its rich inflection and agglutina- 2005).The most problematic area in translation is tion poses many challenges, that forced the lexicon and the role it plays in the act of creat- for manual translation to make the cor- ing deviations in sense and reference based on the pus available. The divergence in lexi- context of its occurrence in texts (Dash, 2013). cal, syntactic and semantic in any pair Indian languages come under Indo-Aryan or of languages makes machine translation Dravidian scripts. Though there are similarities more difficult. And many systems still de- in scripts, there are many issues and challenges pend on rules heavily, that deteriates sys- in translation between languages such as lexical tem performance. In this paper, a study divergences, ambiguities, lexical mismatches, re- on divergence in Malayalam-Tamil lan- ordering, syntactic and semantic issues, structural guages is attempted at source language changes etc. Human translators try to choose the analysis to make translation process easy. -

Introduction to Brahui

South Asian Language Resource Center Workshop on Languages of Afghanistan and neighboring areas, December 12-14, 2003 Brahui - Notes Elena Bashir Brahui is a Northern Dravidian language, spoken mainly in Pakistani Balochistan. There are about 2,000,000 speakers in Pakistan, 200,000 in Afghanistan, 10,000 in Iran, and a small number in Turkestan (http://www.ethnologue.com). There are two theories of how Brahui speakers come to be in Balochistan, whereas the speakers of other Dravidian languages are concentrated in South India. One group of scholars holds that the Brahui speakers in Balochistan are a relic group, left behind when the main body of Dravidian speakers continued south into southern India. The other maintains that Brahui speakers first went farther south, and then returned in a northwest direction to their present position in Balochistan. The map on the following page diagrams these two views. Brahui as a Dravidian language. The following table compares some aspects of Brahui lexicon and grammar with Indo-Aryan Urdu and other Dravidian languages. Although Brahui has been influenced massively by Balochi, it retains enough basic lexicon and morphology to identify it as Dravidian. Brahui compared with Indo-Aryan and Dravidian Representative Brahui Other Dravidian Indo-Aryan (Urdu) First 3 numerals ek '1' asi '1' oR (Drav. root) '1' do '2' iraa '2' ir- (Drav. root) '2' tiin 'e' musi '3' mur (Drav. rot) '3' Interrogative k-, e.g. kyaa 'what' a-, e.g. Telugu emi 'why' element ant 'what' Negative n- e.g. na 'not' separate negative -a- general Drav. m- e.g.