Bulletin of the Indus Research Centre

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cockfighting

Vol XL No 2 Summer 2017 Journal of Beauty Without Cruelty - India An International Educational Charitable Trust for Animal Rights In this Issue: Milk Meat Leather nexus Xenotransplantation Animal Sacrifice Plumage Cockfighting Beauty Without Cruelty - India 4 Prince of Wales Drive, Wanowrie, Pune 411 040 Tel: +91 20 2686 1166 Fax: +91 20 2686 1420 From E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.bwcindia.org my Desk… Why? Contents Beauty Without Cruelty can not understand why people From my Desk… _______________________ this page want jallikattu, bailgadichi AP Cockfighting Ban Round-up _________________ 2 sharyat and kambala to be Fact, not Fancy Plumage _______________________ 6 held. These “sports” inflict At the Ekvira Devi Jatra 2017 __________________ 10 great cruelty upon bulls and buffaloes. Humans get severely Readers Write _______________________________ 11 injured also, and many die. Yet, FYI Xenotransplantation ______________________ 12 politicians are finding ways to Vegan Recipe Jackfruit __________ inside back cover circumspect the law and allow these events to occur. Surely we do not need to replicate cruelty to animals from our ancient customs, more so after having given them up. Our struggle to stop animals being exploited for entertainment has re-started. Saved from Slaughter laughter house rules have Salways – yes, always – existed, but have never been implemented in toto. Butchers and governments are to blame. Beauty Without Cruelty Published and edited by Every year lakhs of animals Diana Ratnagar is a way of life which causes Chairperson, BWC - India would not have been killed no creature of land, sea or air Designed by Dinesh Dabholkar if unlicensed units had been terror, torture or death Printed at Mudra closed. -

The Spread of Sanskrit* (Published In: from Turfan to Ajanta

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Serveur académique lausannois Spread of Sanskrit 1 Johannes Bronkhorst Section de langues et civilisations orientales Université de Lausanne Anthropole CH-1009 Lausanne The spread of Sanskrit* (published in: From Turfan to Ajanta. Festschrift for Dieter Schlingloff on the Occasion of his Eightieth Birthday. Ed. Eli Franco and Monika Zin. Lumbini International Research Institute. 2010. Vol. 1. Pp. 117-139.) A recent publication — Nicholas Ostler’s Empires of the Word (2005) — presents itself in its subtitle as A Language History of the World. Understandably, it deals extensively with what it calls “world languages”, languages which play or have played important roles in world history. An introductory chapter addresses, already in its title, the question “what it takes to be a world language”. The title also provides a provisional answer, viz. “you never can tell”, but the discussion goes beyond mere despair. It opposes the “pernicious belief” which finds expression in a quote from J. R. Firth, a leading British linguist of the mid-twentieth century (p. 20): “World powers make world languages [...] Men who have strong feelings directed towards the world and its affairs have done most. What the humble prophets of linguistic unity would have done without Hebrew, Arabic, Latin, Sanskrit and English, it it difficult to imagine. Statesmen, soldiers, sailors, and missionaries, men of action, men of strong feelings have made world languages. They are built on blood, money, sinews, and suffering in the pursuit of power.” Ostler is of the opinion that this belief does not stand up to criticism: “As soon as the careers of languages are seriously studied — even the ‘Hebrew, Arabic, Latin, Sanskrit and English’ that Firth explicitly mentions as examples — it becomes clear that this self-indulgently tough-minded view is no guide at all to what really makes a language capable of spreading.” He continues on the following page (p. -

India Financial Statement

Many top stars donated their time to PETA in elementary school students why elephants don’t order to help focus public attention on cruelty belong in circuses. PETA India’s new petition calling India to animals. Bollywood “villain” Gulshan Grover’s on the government to uphold the ban on jallikattu – sexy PETA ad against leather was released ahead a bull-taming event in which terrified bulls are Financial Statement of Amazon India Fashion Week. Pamela Anderson deliberately disoriented, punched, jumped on, penned a letter to the Chief Minister of Kerala to offer tormented, stabbed and dragged to the ground – REVENUES 30 life-size, realistic and portable elephants made of has been signed by top film stars, including Contributions 71,098,498 bamboo and papier-mâché to replace live elephants in Sonakshi Sinha, Jacqueline Fernandez, Other Income 335,068 the Thrissur Pooram parade. Tennis player Sania Mirza Bipasha Basu, John Abraham, Raveena Tandon, and the stars of Comedy Nights With Kapil teamed Vidyut Jammwal, Shilpa Shetty, Kapil Sharma, Total Revenues 71,433,566 up with PETA for ads championing homeless cat and Amy Jackson, Athiya Shetty, Sonu Sood, dog adoption. Kapil Sharma, the host of that show, Richa Chadha and Vidya Balan and cricketers was also named PETA’s 2015 Person of the Year for Virat Kohli and Shikhar Dhawan. OPERATING EXPENSES his dedication to Programmes helping animals. PETA gave a Awareness Programme 37,434,078 Just before Humane Science Compassionate Citizen Project 3,998,542 World Music Award to the Membership Development 13,175,830 Day, members Mahatma Gandhi- Management and General Expenses 16,265,248 of folk band Doerenkamp The Raghu Centre, for their Dixit Project monumental Total Operating Expenses 70,873,698 starred in a PETA progress in Youth campaign pushing for ad against cruelty humane legislation CHANGE IN NET ASSETS 559,868 to animals in Photo: © Guarav Sawn and reducing and Net Assets Beginning of Year 5,086,144 the circus. -

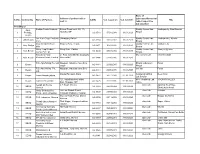

S.L.No. Commodity Name of Packers Address of Packers with E- Mail Id

Name of Address of packers with e- Laboratory/Comercial S.l.No. Commodity Name of Packers CA No. C.A. issued on C.A. valid till TBL mail id /SGL/Cooperative Lab attached R.O.Bhopal Aata, Poddar Foods Products Behind Rewa hotel, NH- 78, Quality Control Lab Vindhyavelly, Maa Birasani 1 Porridge, Shahdol, MP A/2 3518 07.08.2018 31.03.2023 Bhopal Besan Lav Kush Corp. Products Gairatganj, Raisen Quality Control Lab Vindhya velly, Ajiveka 2 Atta Besan A/2-3384 11.10.2013 31.03.2023 Com. Bhopal Maa GAYATRI Flour Khajuria Bina, Dewas Quality control Lab, Vindya Velly 3 Atta, Daliya A/2 3471 15.09.2016 31.03.2021 Mills Bhopal Sironj Crop Produce Sironj Distt- Vidisha Quality Control Lab Sironj & Ajjevika 4 Atta, Besan A/2-3404 03.03.2014 31.03.2019 Comp. Pvt. Ltd Bhopal Kaila Devi Food 21 Ram Janki Mandir Jiwajiganj Morena Ana Lab Chambal Gold 5 Atta, Besan Products Private Limited Morena MP A/2 3464 22/06/2016 31.03.2021 R.B. Agro Milling Pvt. Ltd. Naugaon Industries Area Bina, Bhopal Laboratory Paras 6 Besan A/2-3444 26/06/2015 31/03/2020 Sagar Bhopal R.B. Agro Milling Pvt. Naugoan, Industrial area,Bina own lab Paras 7 Besan A/2-3444 29.05.2015 31.03.2020 Ltd. Mauza Ramgarh, Datia Gwaliar Analytical Deep Gold 8 Besan Tiwari Masala Udyog A/2 3477 14.12.2016 31..03.2021 Lab,Gwaliar 121, Industrial Area, Maksi, MPP. Analytical Lab VINDHYA VALLEY 9 Besan Lakshmi Besan Mill A/2 3476 20.10.2016 31..03.2021 Distt. -

Women Resurrecting Poultry Biodiversity and Livelihoods

Women resurrecting poultry biodiversity and livelihoods Source South Asia Pro Poor Livestock Policy Program (SAPPLPP) Keywords Poultry, women, partnerships Country of first practice India ID and publishing year 7681 and 2012 Sustainable Development Goals No poverty, gender equality, and life on land Summary The Aseel is reared under backyard poultry by women (from bird selection to sale). management systems and is a vital source Today this indigenous breed, which has its of meat and income. However, this bird is lineage from the original Red Jungle Fowl, is threatened due to high production losses, threatened due to high production losses, infectious diseases and policies promoting infectious diseases and policies promoting non-local breeds. This practice describes non-local breeds. As a result, although how disease prevention and bio-diversity a farmer could potentially earn over conservation strategies helped women Rs. 4 000 per adult hen yearly (see Table 1), farmers in preserving the Aseel. actual earnings are less than half of this, due to losses resulting from egg spoilage / Description infertile eggs and chick mortality. 1. Background Figure 1. Women resurrecting poultry biodiversity and livelihoods The Aseel is an important part of Âdivâsîs culture in the East Godavari district. Âdivâsîs is the Devanagri word for original inhabitants and is an umbrella term for a heterogeneous set of ethnic and tribal groups believed to be the aboriginal population of India and comprise a substantial indigenous minority. Tribal people constitute 8.2 percent of the © FAO/TECA nation’s total population, over 84 million people according to the 2001 census. Adivasi societies are particularly present in the Indian states of Orissa, Madhya Annual poultry mortality is also remarkably Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Rajasthan, Gujarat, high at 70 to 80 percent due to Ranikhet Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh, Bihar, (New Castle disease), Fowl Jharkhand, West Bengal, Mizoram and other Pox, Bacterial White diarrhoea North-Eastern states, and the Andaman and etc. -

TRIBAL COMMUNITIES of ODISHA Introduction the Eastern Ghats Are

TRIBAL COMMUNITIES OF ODISHA Introduction The Eastern Ghats are discontinuous range of mountain set along Eastern coast. They are located between 11030' and 220N latitude and 76050' and 86030' E longitude in a North-East to South-West strike. It covers total area of around 75,000 sq. km. Eastern Ghats are often referred to as “Estuaries of India”, because of high rainfall and fertile land that results into better crops1. Eastern Ghat area is falling under tropical monsoon climate receiving rainfall from both southwest monsoon and northeast retreating monsoon. The northern portion of the Ghats receives rainfall from 1000 mm to 1600 mm annually indicating sub-humid climate. The Southern part of Ghats receives 600 mm to 1000 mm rainfall exhibiting semi arid climate2. The Eastern Ghats is distributed mainly in four States, namely, Odisha, Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu and Karnataka. The part of Eastern Ghats found in the Odisha covers 18 districts, Andhra Pradesh 15 districts and Tamil Nadu in 9 districts while Karnataka Eastern Ghats falls in part of Chamrajnagar and Kolar3. Most of the tribal population in the State is concentrated in the Eastern Ghats of high attitude zone. The traditional occupations of the tribes vary from area to area depending on topography, availability of forests, land, water etc. for e.g. Chenchus tribes of interior forests of Nallamalai Hills gather minor forest produce and sell it in market for livelihood while Konda Reddy, Khond, Porja and Savara living on hill slopes pursue slash and burn technique for cultivation on hill slopes. The Malis of Visakhapatnam (Araku) Agency area are expert vegetable growers. -

May, 2011 Subject: Monthly Media Dossier Medium Appeared In

MEDIA DOSSIER Period Covered: May, 2011 Subject: Monthly Media Dossier Medium Appeared in: Print & Online For internal circulation only Monthly Media Dossier May 2011 Page 1 of 121 PERCEPT AND INDUSTRY NEWS Percept Limited Pg 03 ENTERTAINMENT Percept Sports and Entertainment PDM Pg 23 - Percept Activ Pg 28 - Percept ICE Pg 35 - Percept Sports _____ - Percept Entertainment _____ P9 INTEGRATED Pg 40 PERCEPT TALENT Pg 42 Content Percept Pictures Pg 43 Asset Percept IP _____ MEDIA ALLIED MEDIA Pg 46 PERCEPT OUT OF HOME Pg 50 PERCEPT KNORIGIN Pg 52 COMMUNICATIONS Advertising PERCEPT/H Pg 53 MASH _____ IBD INDIA _____ Percept Gulf _____ Hakuhodo Percept Pg 59 Public Relations PERCEPT PROFILE INDIA Pg 63 IMC PERSPECTRUM _____ INDUSTRY & COMPETITOR NEWS Pg 66 Monthly Media Dossier May 2011 Page 2 of 121 PERCEPT LIMITED SLAMFEST Source: Experiential Marketing, Date: May, 2011 *************** Shailendra Singh, Percept Picture Company Source: Box Office India , Date: May 28. 2011 ******************** Marketing to men as potential customers! Source: Audiencematters.com; Date: May 31, 2011 Monthly Media Dossier May 2011 Page 3 of 121 Men are quite different from the females not only in their physical appearance but also when it comes to their buying habit. Marketers cannot market for men and women in the same way. It's not a simple transformation of changing colors, fonts or packaging. Men and women are different biologically, psychologically and socially. There are lots of things that marketers should keep in mind before targeting men. Men believe in purchase for ‘now’. Unlike women who don’t have anything particular in mind but still can shop for hours, men buy what they need in the recent future. -

Mint Building S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU

pincode officename districtname statename 600001 Flower Bazaar S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600001 Chennai G.P.O. Chennai TAMIL NADU 600001 Govt Stanley Hospital S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600001 Mannady S.O (Chennai) Chennai TAMIL NADU 600001 Mint Building S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600001 Sowcarpet S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600002 Anna Road H.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600002 Chintadripet S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600002 Madras Electricity System S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600003 Park Town H.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600003 Edapalayam S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600003 Madras Medical College S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600003 Ripon Buildings S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600004 Mandaveli S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600004 Vivekananda College Madras S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600004 Mylapore H.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600005 Tiruvallikkeni S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600005 Chepauk S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600005 Madras University S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600005 Parthasarathy Koil S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600006 Greams Road S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600006 DPI S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600006 Shastri Bhavan S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600006 Teynampet West S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600007 Vepery S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600008 Ethiraj Salai S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600008 Egmore S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600008 Egmore ND S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600009 Fort St George S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600010 Kilpauk S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600010 Kilpauk Medical College S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600011 Perambur S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600011 Perambur North S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600011 Sembiam S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600012 Perambur Barracks S.O Chennai -

Standard Seven Term - I Volume - 3

GOVERNMENT OF TAMILNADU STANDARD SEVEN TERM - I VOLUME - 3 SCIENCE SOCIAL SCIENCE A publication under Free Textbook Programme of Government of Tamil Nadu Department of School Education Untouchability is Inhuman and a Crime VII Std Science Term-1 EM Introduction Pages.indd 1 09-03-2019 2.44.09 PM Government of Tamil Nadu First Edition - 2019 (Published under New Syllabus in Trimester Pattern) NOT FOR SALE Content Creation The wise possess all State Council of Educational Research and Training © SCERT 2019 Printing & Publishing Tamil NaduTextbook and Educational Services Corporation www.textbooksonline.tn.nic.in II VII Std Science Term-1 EM Introduction Pages.indd 2 09-03-2019 2.44.09 PM STANDARD SEVEN TERM - I VOLUME - 3 HISTORY 108 7th Social Science_Term I English Unit 01.indd 108 09-03-2019 2.52.24 PM CONTENTS History Unit Titles Page No. 1. Sources of Medieval India 110 2. Emergence of New Kingdoms in North India 100 Emergence of New Kingdoms in South India: 112 3. Later Cholas and Pandyas 4. The Delhi Sultanate 128 Geography 1. Interior of the Earth 143 2. Population and Settlement 171 3. Landforms 188 Civics 1. Equality 196 2. Political Parties 203 Economics 1. Production 200 E - Book Assessment Digi - links Lets use the QR code in the text books ! How ? • Download the QR code scanner from the Google PlayStore/ Apple App Store into your smartphone • Open the QR code scanner application • Once the scanner button in the application is clicked, camera opens and then bring it closer to the QR code in the text book. -

A Contribution to Agrarian History Parvathi Menon

BOOK REVIEW A Contribution to Agrarian History Parvathi Menon Karashima, Noboru (2009), South Indian Society in Transition: Ancient to Medieval, Oxford University Press, New Delhi, pp. 301, Rs 750. The book under review (hereafter Society in Transition) is the latest in a formidable body of scholarly publications by the historian and epigraphist Noboru Karashima on the agrarian history of South India in the ancient and medieval periods. In the book, Karashima chooses an unusual thirteenth-century inscriptional allusion with which to begin his description of historical transition in the region. The statement in this inscription, from Tirukkachchur in Chengalpattu district in Tamil Nadu, was issued in the name of people who described themselves as living in Brahmin villages, Vellala villages, and towns (nagaram) in a locality called Irandayiravelipparru during the reign of the Pandya ruler Jatavarman Sundarapandya. The inscription, the author writes, records the local people’s decision taken on the atrocities of five Brahmana brothers. According to this inscription some chiefs caught the brothers at the request of the local people, but soon the trouble started again and another chief sent soldiers to catch them. Though they caught two of them, the remaining three brothers continued to fight in the forest and killed even the soldiers sent by the Pandyan king.1 The inscription goes on to record the confiscation and sale of property of the five trouble-makers. “These Brahmana brothers have now forgotten the old good habits of Brahmanas and Vellalas,” say the authors of the inscription, “and are steeped in the bad behaviour of the low jatis.” In this reactionary lament Karashima sees the social churning of the age. -

Message Against Racism Delivered

12 | Monday, March 1, 2021 HONG KONG EDITION | CHINA DAILY WORLD Briefly BOLIVIA Message against racism delivered Viceminister dies from COVID19 Rally in Manhattan follows surge in was being investigated as a possible City, 259 incidents against Asian ing. I talked to a family member of The Bolivian government on Satur hate crime. Americans were recorded in the someone who is in hospital as a vic day said Gonzalo Rodriguez, who hate crimes targeting Asian Americans Last year, there were 28 incidents same period, with 81 percent being tim of one of these hate crimes. served as viceminister in charge of of pandemicrelated hate crimes verbal and 12 percent physical. There are so much pain and confu fighting smuggling, has died from By MINLU ZHANG in New York in New York City, but all over this against Asians in New York and two In New York, where Asian Ameri sion.” COVID19. Rodriguez was admitted [email protected] country: Stop Asian hates, stop it so far in 2021, according to the dep cans make up an estimated 16 per April Somboun, a candidate for to hospital two weeks ago after con now,” de Blasio told the crowd. uty inspector of the city’s Anti cent of the population, the violence New York City council District 33, tracting the coronavirus. His situa New York leaders joined hun “Anyone who commits an act of Asian Hate Crimes Task Force, has terrified many. said two of her friends have been tion worsened and he died on Friday dreds of residents at a rally in Man hatred against the AsianAmerican Stewart Loo. -

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS STOCKHOLMIENSIS Stockholm Studies in Social Anthropoplogy 60

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS STOCKHOLMIENSIS Stockholm Studies in Social Anthropoplogy 60 ‘When Women Unite!’ The Making of the Anti-Liquor Movement in Andhra Pradesh, India Marie Larsson Stockholm University © Marie Larsson, Stockholm 2006 ISBN 91-7155-249-9 Cover illustration by G. Srinath Typesetting: Intellecta Docusys Printed in Sweden by Intellecta Docusys, Stockholm 2006 Distributor: Stockholm University Library Contents 1. Introduction……………………….………………………….5 Conceptual Frameworks of Alcohol and Gender…………………………..………….…….9 Conceptual Frameworks of Social Movements and Gender…………………………......14 Anthropological Studies of South India…………….………………..…….………………..21 Andhra Pradesh………………….…………………………………………………………….22 Methodology………………………………………………………...……..…………..…...….25 An Outline of the Book…..………………..……………..…………………..………………..28 2. How Temperance Became A Woman’s Issue: A Review of Social Movements from the Colonial Period Onwards……………………………...…..…31 The Social Reform Movement…………………………………………….………...………31 The Temperance Movement……………………………..…………………………….…...33 The Caste Association…………………………………..………………….…………….….35 The Nationalist Movement…………………………….………………………..……….…...37 The Extremists………………………………..….…………….……………….……..37 Gandhi…………………………………………….…..…….…………………….…...38 Women’s Movement………………………….…………..…………….….…………41 The Post-Independence Period………………………….………………………...……..…41 The Women’s Movement…………………………………………….…….………...44 Protests Against Alcohol Consumption…………………….……………..………..45 Mobilization for Women’s Rights and Temperance in Andhra Pradesh………..……….48