Social Sciences a Journal of ICFAI University, Nagaland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dravidian Languages

THE DRAVIDIAN LANGUAGES BHADRIRAJU KRISHNAMURTI The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 2RU, UK 40 West 20th Street, New York, NY 10011–4211, USA 477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, VIC 3207, Australia Ruiz de Alarc´on 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town 8001, South Africa http://www.cambridge.org C Bhadriraju Krishnamurti 2003 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2003 Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeface Times New Roman 9/13 pt System LATEX2ε [TB] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 0521 77111 0hardback CONTENTS List of illustrations page xi List of tables xii Preface xv Acknowledgements xviii Note on transliteration and symbols xx List of abbreviations xxiii 1 Introduction 1.1 The name Dravidian 1 1.2 Dravidians: prehistory and culture 2 1.3 The Dravidian languages as a family 16 1.4 Names of languages, geographical distribution and demographic details 19 1.5 Typological features of the Dravidian languages 27 1.6 Dravidian studies, past and present 30 1.7 Dravidian and Indo-Aryan 35 1.8 Affinity between Dravidian and languages outside India 43 2 Phonology: descriptive 2.1 Introduction 48 2.2 Vowels 49 2.3 Consonants 52 2.4 Suprasegmental features 58 2.5 Sandhi or morphophonemics 60 Appendix. Phonemic inventories of individual languages 61 3 The writing systems of the major literary languages 3.1 Origins 78 3.2 Telugu–Kannada. -

Dyron Daughrity

Hinduisms, Christian Missions, and the Tinnevelly Shanars: th A Study of Colonial Missions in 19 Century India DYRON B. DAUGHRITY, PHD Written During 5th Year, PhD Religious Studies University of Calgary Calgary, Alberta Protestant Christian missionaries first arrived in south India in 1706 when two young Germans began their work at a Danish colony on India's southeastern coast known as Tranquebar. These early missionaries, Bartholomaeus Ziegenbalg and Heinrich Pluetschau, brought with them a form of Lutheranism that emphasized personal piety and evangelistic fervour. They had little knowledge of what to expect from the peoples they were about to encounter. They were entering a foreign culture with scarcely sufficient preparation, but with the optimistic view that they would succeed in their task of bringing Christianity to the land of the “Hindoos.”1 The missionaries continued to come and by 1801, when the entire district of Tinnevelly (in south India) had been ceded to the British, there were pockets of Protestant Christianity all over the region. For the missionaries, the ultimate goal was conversion of the “heathen.” Vast resources were contributed by various missionary societies in Europe and America in order to establish churches, 1 In 2000, an important work by D. Dennis Hudson entitled Protestant Origins in India: Tamil Evangelical Christians, 1706-1835 (Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 2000) brought to light this complex and fascinating story of these early missionaries encountering for the first time an entirely new culture, language, and religion. This story sheds significant insight on the relationship between India and the West, particularly regarding religion and culture, and serves as a backdrop for the present research. -

Community List

ANNEXURE - III LIST OF COMMUNITIES I. SCHEDULED TRIB ES II. SCHEDULED CASTES Code Code No. No. 1 Adiyan 2 Adi Dravida 2 Aranadan 3 Adi Karnataka 3 Eravallan 4 Ajila 4 Irular 6 Ayyanavar (in Kanyakumari District and 5 Kadar Shenkottah Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 6 Kammara (excluding Kanyakumari District and 7 Baira Shenkottah Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 8 Bakuda 7 Kanikaran, Kanikkar (in Kanyakumari District 9 Bandi and Shenkottah Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 10 Bellara 8 Kaniyan, Kanyan 11 Bharatar (in Kanyakumari District and Shenkottah 9 Kattunayakan Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 10 Kochu Velan 13 Chalavadi 11 Konda Kapus 14 Chamar, Muchi 12 Kondareddis 15 Chandala 13 Koraga 16 Cheruman 14 Kota (excluding Kanyakumari District and 17 Devendrakulathan Shenkottah Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 18 Dom, Dombara, Paidi, Pano 15 Kudiya, Melakudi 19 Domban 16 Kurichchan 20 Godagali 17 Kurumbas (in the Nilgiris District) 21 Godda 18 Kurumans 22 Gosangi 19 Maha Malasar 23 Holeya 20 Malai Arayan 24 Jaggali 21 Malai Pandaram 25 Jambuvulu 22 Malai Vedan 26 Kadaiyan 23 Malakkuravan 27 Kakkalan (in Kanyakumari District and Shenkottah 24 Malasar Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 25 Malayali (in Dharmapuri, North Arcot, 28 Kalladi Pudukkottai, Salem, South Arcot and 29 Kanakkan, Padanna (in the Nilgiris District) Tiruchirapalli Districts) 30 Karimpalan 26 Malayakandi 31 Kavara (in Kanyakumari District and Shenkottah 27 Mannan Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 28 Mudugar, Muduvan 32 Koliyan 29 Muthuvan 33 Koosa 30 Pallayan 34 Kootan, Koodan (in Kanyakumari District and 31 Palliyan Shenkottah Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 32 Palliyar 35 Kudumban 33 Paniyan 36 Kuravan, Sidhanar 34 Sholaga 39 Maila 35 Toda (excluding Kanyakumari District and 40 Mala Shenkottah Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 41 Mannan (in Kanyakumari District and Shenkottah 36 Uraly Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 42 Mavilan 43 Moger 44 Mundala 45 Nalakeyava Code III (A). -

Persistence of Caste in South India - an Analytical Study of the Hindu and Christian Nadars

Copyright by Hilda Raj 1959 , PERSISTENCE OF CASTE IN SOUTH INDIA - AN ANALYTICAL STUDY OF THE HINDU AND CHRISTIAN NADARS by Hilda Raj Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The American University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Signatures of Committee: . Chairman: D a t e ; 7 % ^ / < f / 9 < r f W58 7 a \ The American University Washington, D. 0. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am deeply thankful to the following members of my Dissertation Committee for their guidance and sug gestions generously given in the preparation of the Dissertation: Doctors Robert T. Bower, N. G. D. Joardar, Lawrence Krader, Harvey C. Moore, Austin Van der Slice (Chairman). I express my gratitude to my Guru in Sociology, the Chairman of the above Committee - Dr. Austin Van der Slice, who suggested ways for the collection of data, and methods for organizing and presenting the sub ject matter, and at every stage supervised the writing of my Dissertation. I am much indebted to the following: Dr. Horace Poleman, Chief of the Orientalia Di vision of the Library of Congress for providing facilities for study in the Annex of the Library, and to the Staff of the Library for their unfailing courtesy and readi ness to help; The Librarian, Central Secretariat-Library, New Delhi; the Librarian, Connemara Public Library, Madras; the Principal in charge of the Library of the Theological Seminary, Nazareth, for privileges to use their books; To the following for helping me to gather data, for distributing questionnaire forms, collecting them after completion and mailing them to my address in Washington: Lawrence Gnanamuthu (Bombay), Dinakar Gnanaolivu (Madras), S. -

Nadarin Pdf, Epub, Ebook

NADARIN PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Leo Lionni,Teresa Mlawer | 24 pages | 30 Sep 2005 | Lectorum Publications | 9781930332805 | English, Spanish | New York, NY, United States Nadarin PDF Book Swimmy , A. Now customize the name of a clipboard to store your clips. They were also very caste conscious. The support included urging their own community members to allow use of their schools, tanks, temples and wells by other communities. Any Condition Any Condition. Impersonate a cat, then when questioned again say you're a stray. She wants you to retrieve an amulet from Arkion. Raid the trapped drawers and steal the Rogue Stone. About this product. Namespaces Article Talk. In the early nineteenth century, the Nadars were a community mostly engaged in the palmyra industry, including the production of toddy. Kamaraj , whose opinions had originally been disliked by his own community. Hardgrave conjectures that the Nadars of Southern Travancore migrated there from Tirunelveli in the 16th century after the invasion of Tirunelveli by the Raja of Travancore. These include procedures relating to birth, adulthood, marriage and death. Password forgot password? Cookie Settings explains the different cookies we use. Forrester University of South Carolina press. In situations where the matter went to court, the Sangam would not provide financial support for the Nadar claimant to contest the case, but would rather see that the claim is properly heard. No notes for slide. Staycation by M. Please visit our current hours of operation for our outlets and amenities and a complete list of our enhanced hygiene safety measures. Additional information about this order and a list of high risk states may be found by clicking here. -

Police Matters: the Everyday State and Caste Politics in South India, 1900�1975 � by Radha Kumar

PolICe atter P olice M a tte rs T he v eryday tate and aste Politics in South India, 1900–1975 • R a dha Kumar Cornell unIerIt Pre IthaCa an lonon Copyright 2021 by Cornell University The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License: https:creativecommons.orglicensesby-nc-nd4.0. To use this book, or parts of this book, in any way not covered by the license, please contact Cornell University Press, Sage House, 512 East State Street, Ithaca, New ork 14850. Visit our website at cornellpress.cornell.edu. First published 2021 by Cornell University Press Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Kumar, Radha, 1981 author. Title: Police matters: the everyday state and caste politics in south India, 19001975 by Radha Kumar. Description: Ithaca New ork: Cornell University Press, 2021 Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2021005664 (print) LCCN 2021005665 (ebook) ISBN 9781501761065 (paperback) ISBN 9781501760860 (pdf) ISBN 9781501760877 (epub) Subjects: LCSH: Police—India—Tamil Nadu—History—20th century. Law enforcement—India—Tamil Nadu—History—20th century. Caste— Political aspects—India—Tamil Nadu—History. Police-community relations—India—Tamil Nadu—History—20th century. Caste-based discrimination—India—Tamil Nadu—History—20th century. Classification: LCC HV8249.T3 K86 2021 (print) LCC HV8249.T3 (ebook) DDC 363.20954820904—dc23 LC record available at https:lccn.loc.gov2021005664 LC ebook record available at https:lccn.loc.gov2021005665 Cover image: The Car en Route, Srivilliputtur, c. 1935. The British Library Board, Carleston Collection: Album of Snapshot Views in South India, Photo 6281 (40). -

Dictionary of Martyrs: India's Freedom Struggle

DICTIONARY OF MARTYRS INDIA’S FREEDOM STRUGGLE (1857-1947) Vol. 5 Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu & Kerala ii Dictionary of Martyrs: India’s Freedom Struggle (1857-1947) Vol. 5 DICTIONARY OF MARTYRSMARTYRS INDIA’S FREEDOM STRUGGLE (1857-1947) Vol. 5 Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu & Kerala General Editor Arvind P. Jamkhedkar Chairman, ICHR Executive Editor Rajaneesh Kumar Shukla Member Secretary, ICHR Research Consultant Amit Kumar Gupta Research and Editorial Team Ashfaque Ali Md. Naushad Ali Md. Shakeeb Athar Muhammad Niyas A. Published by MINISTRY OF CULTURE, GOVERNMENT OF IDNIA AND INDIAN COUNCIL OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH iv Dictionary of Martyrs: India’s Freedom Struggle (1857-1947) Vol. 5 MINISTRY OF CULTURE, GOVERNMENT OF INDIA and INDIAN COUNCIL OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH First Edition 2018 Published by MINISTRY OF CULTURE Government of India and INDIAN COUNCIL OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH 35, Ferozeshah Road, New Delhi - 110 001 © ICHR & Ministry of Culture, GoI No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. ISBN 978-81-938176-1-2 Printed in India by MANAK PUBLICATIONS PVT. LTD B-7, Saraswati Complex, Subhash Chowk, Laxmi Nagar, New Delhi 110092 INDIA Phone: 22453894, 22042529 [email protected] State Co-ordinators and their Researchers Andhra Pradesh & Telangana Karnataka (Co-ordinator) (Co-ordinator) V. Ramakrishna B. Surendra Rao S.K. Aruni Research Assistants Research Assistants V. Ramakrishna Reddy A.B. Vaggar I. Sudarshan Rao Ravindranath B.Venkataiah Tamil Nadu Kerala (Co-ordinator) (Co-ordinator) N. -

Department of History Periyar E.V.R

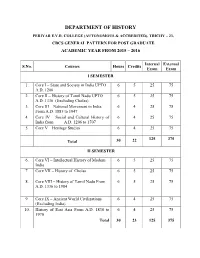

DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY PERIYAR E.V.R. COLLEGE (AUTONOMOUS & ACCREDITED), TRICHY – 23, CBCS GENERAL PATTERN FOR POST GRADUATE ACADEMIC YEAR FROM 2015 – 2016 Internal External S.No. Courses Hours Credits Exam Exam I SEMESTER 1. Core I – State and Society in India UPTO 6 5 25 75 A.D. 1206 2. Core II – History of Tamil Nadu UPTO 6 5 25 75 A.D. 1336 (Excluding Cholas) 3. Core III – National Movement in India 6 4 25 75 From A.D. 1885 to 1947 4. Core IV – Social and Cultural History of 6 4 25 75 India from A.D. 1206 to 1707 5. Core V – Heritage Studies 6 4 25 75 125 375 Total 30 22 II SEMESTER 6. Core VI – Intellectual History of Modern 6 5 25 75 India 7. Core VII – History of Cholas 6 5 25 75 8. Core VIII – History of Tamil Nadu From 6 5 25 75 A.D. 1336 to 1984 9. Core IX – Ancient World Civilizations 6 4 25 75 (Excluding India) 10. History of East Asia From A.D. 1830 to 6 4 25 75 1970 Total 30 23 125 375 III SEMESTER 11. Core XI – History of Political Thought 6 5 25 75 12. Core XII – Historiography 6 5 25 75 13. Core XIII – Socio - Economic and 6 5 25 75 Cultural History of India From A.D. 1707 to 1947 14. Core Based Elective - I: Contemporary 6 4 25 75 Issues in India 15. Core Based Elective - II: Dravidian 6 4 25 75 Movement Total 30 23 125 375 IV SEMESTER 16. -

CENTRAL LIST of Obcs for the STATE of TAMILNADU Entry No

CENTRAL LIST OF OBC FOR THE STATE OF TAMILNADU E C/Cmm Rsoluti No. & da N. Agamudayar including 12011/68/93-BCC(C ) dt 10.09.93 1 Thozhu or Thuluva Vellala Alwar, -do- Azhavar and Alavar 2 (in Kanniyakumari district and Sheoncottah Taulk of Tirunelveli district ) Ambalakarar, -do- 3 Ambalakaran 4 Andi pandaram -do- Arayar, -do- Arayan, 5 Nulayar (in Kanniyakumari district and Shencottah taluk of Tirunelveli district) 6 Archakari Vellala -do- Aryavathi -do- 7 (in Kanniyakumari district and Shencottah taluk of Tirunelveli district) Attur Kilnad Koravar (in Salem, South 12011/68/93-BCC(C ) dt 10.09.93 Arcot, 12011/21/95-BCC dt 15.05.95 8 Ramanathapuram Kamarajar and Pasumpon Muthuramadigam district) 9 Attur Melnad Koravar (in Salem district) -do- 10 Badagar -do- Bestha -do- 11 Siviar 12 Bhatraju (other than Kshatriya Raju) -do- 13 Billava -do- 14 Bondil -do- 15 Boyar -do- Oddar (including 12011/68/93-BCC(C ) dt 10.09.93 Boya, 12011/21/95-BCC dt 15.05.95 Donga Boya, Gorrela Dodda Boya Kalvathila Boya, 16 Pedda Boya, Oddar, Kal Oddar Nellorepet Oddar and Sooramari Oddar) 17 Chakkala -do- Changayampadi -do- 18 Koravar (In North Arcot District) Chavalakarar 12011/68/93-BCC(C ) dt 10.09.93 19 (in Kanniyakumari district and Shencottah 12011/21/95-BCC dt 15.05.95 taluk of Tirunelveli district) Chettu or Chetty (including 12011/68/93-BCC(C ) dt 10.09.93 Kottar Chetty, 12011/21/95-BCC dt 15.05.95 Elur Chetty, Pathira Chetty 20 Valayal Chetty Pudukkadai Chetty) (in Kanniyakumari district and Shencottah taluk of Tirunelveli district) C.K. -

Carey, H. (2020). Babylon, the Bible and the Australian Aborigines. in G

Carey, H. (2020). Babylon, the Bible and the Australian Aborigines. In G. Atkins, S. Das, & B. Murray (Eds.), Chosen Peoples: The Bible, Race, and Nation in the Long Nineteenth Century (pp. 55-72). (Studies in Imperialism). Manchester University Press. Peer reviewed version Link to publication record in Explore Bristol Research PDF-document This is the author accepted manuscript (AAM). The final published version (version of record) is available online via Manchester University Press at https://manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk/9781526143068/ . Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher University of Bristol - Explore Bristol Research General rights This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the reference above. Full terms of use are available: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/red/research-policy/pure/user-guides/ebr-terms/ Part I: Peoples and Lands Babylon, the Bible and the Australian Aborigines Hilary M. Carey [God] hath made of one blood all nations of men for to dwell on all the face of the earth, and hath determined the times before appointed, and the bounds of their habitation (Acts 17:26. KJV) 'One Blood': John Fraser and the Origins of the Aborigines In 1892 Dr John Fraser (1834-1904), a schoolteacher from Maitland, New South Wales, published An Australian Language, a work commissioned by the government of New South Wales for display in Chicago at the World's Columbian Exposition (1893). 1 Fraser's edition was just one of a range of exhibits selected to represent the products, industries and native cultures of the colony to the eyes of the world.2 But it was much more than a showpiece or a simple re-printing of the collected works of Lancelot Threlkeld (1788-1859), the 1 John Fraser, ed. -

Genetic Study of Dravidian Castes of Tamil Nadu

c Indian Academy of Sciences RESEARCH NOTE Genetic study of Dravidian castes of Tamil Nadu S. KANTHIMATHI, M. VIJAYA and A. RAMESH Department of Genetics, Dr ALM PGIBMS, University of Madras, Taramani, Chennai 600 113, India Introduction The present study was carried out in Tamil Nadu, one of southern states of India, with a population of about 62 million The origin and settlement of Indian people still intrigues sci- people (Census of India 2001). Based on the religion, caste entists studying the impact of past and modern migrations and socio-economic status, over 400 endogamous groups are on the genetic diversity and structure of contemporary pop- present in this state, and their size and distribution varies ulations. About 10,000 years ago, proto-Dravidian Neolithic widely. They are known to have received extensive gene flow farmers from Afghanistan entered the Indian subcontinent, from different caste and linguistic groups of other regions of and were later displaced southwards by a large influx of India. Thus, the biological status of the present-day groups ∼ Indo–European speakers 3500 years ago (Majumder et al. can be considered as ‘immigrants’ at varying periods of time. 1999). The present study aims to describe the genetic diver- Many of the caste groups have subcastes maintaining endog- sity and relationships between the Dravidian caste popula- amous status to some extent (Singh 1998). tions of Tamil Nadu, in an attempt to better understand the Insertion by retroposition of mobile genomic elements contemporary people of this state. We studied nine human- such as the Alu family is a dynamic type of genetic change / specific indels (insertion deletion polymorphisms) in DNA in the human genome (Rowold and Herrera 2000). -

Black Europeans, the Indian Coolies and Empire: Colonialisation and Christianized Indians in Colonial Malaya & Singapore, C

Black Europeans, the Indian Coolies and Empire: Colonialisation and Christianized Indians in Colonial Malaya & Singapore, c. 1870s - c. 1950s By Marc Rerceretnam A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of Sydney. February, 2002. Declaration This thesis is based on my own research. The work of others is acknowledged. Marc Rerceretnam Acknowledgements This thesis is primarily a result of the kindness and cooperation extended to the author during the course of research. I would like to convey my thanks to Mr. Ernest Lau (Methodist Church of Singapore), Rev. Fr. Aloysius Doraisamy (Church of Our Lady of Lourdes, Singapore), Fr. Devadasan Madalamuthu (Church of St. Francis Xavier, Melaka), Fr. Clement Pereira (Church of St. Francis Xavier, Penang), the Bukit Rotan Methodist Church (Kuala Selangor), the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies (Singapore), National Archives of Singapore, Southeast Asia Room (National Library of Singapore), Catholic Research Centre (Kuala Lumpur), Suara Rakyat Malaysia (SUARAM), Mr. Clement Liew Wei Chang, Brother Oliver Rodgers (De Lasalle Provincialate, Petaling Jaya), Mr. P. Sakthivel (Seminari Theoloji Malaysia, Petaling Jaya), Ms. Jacintha Stephens, Assoc. Prof. J. R. Daniel, the late Fr. Louis Guittat (MEP), my supervisors Assoc. Prof. F. Ben Tipton and Dr. Lily Rahim, and the late Prof. Emeritus S. Arasaratnam. I would also like to convey a special thank you to my aunt Clarice and and her husband Alec, sister Caryn, my parents, aunts, uncles and friends (Eli , Hai Long, Maura and Tian) in Singapore, Kuala Lumpur and Penang, who kindly took me in as an unpaying lodger.