Locating the Vernacular and the Making of Modern Malayalam

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Accused Persons Arrested in Palakkad District from 18.10.2015 to 24.10.2015

Accused Persons arrested in Palakkad district from 18.10.2015 to 24.10.2015 Name of the Name of Name of the Place at Date & Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police Arresting father of Address of Accused which Time of which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Officer, Rank Accused Arrested Arrest accused & Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Near Village Office, T.K. Muhammed Noorani 1531/15 U/s Town South 1 Riyas 32 Puthunagaram, 18.10.15 Radhakrishnan, Bail by Police Musthafa Gramam 151 CRPC PS Palakkad Addl SI of Police 35/I, Iind Street, Rose T.K. Muhammed Noorani 1531/15 U/s Town South 2 Lyakhath Ali 42 Garden, South 18.10.15 Radhakrishnan, Bail by Police Rafi Gramam 151 CRPC PS Ukkadam, Coimbatore Addl SI of Police T.K. Karimbukada, Noorani 1531/15 U/s Town South 3 Riyasudheen Sirajudheen 29 18.10.15 Radhakrishnan, Bail by Police Coimbatore Gramam 151 CRPC PS Addl SI of Police T.K. Basheer Pothanoor, Noorani 1531/15 U/s Town South 4 Safi Ahammed 32 18.10.15 Radhakrishnan, Bail by Police Ahammed Coimbatore Gramam 151 CRPC PS Addl SI of Police Al Ameen Colony, T.K. Muhammed Noorani 1531/15 U/s Town South 5 Shahul Hameed 27 South Ukkadam, 18.10.15 Radhakrishnan, Bail by Police Yousaf Gramam 151 CRPC PS Coimbatore Addl SI of Police Husaya Plastic, T.K. Noormuhamme Noorani 1531/15 U/s Town South 6 Hidayathulla 36 Chikanampara, 18.10.15 Radhakrishnan, Bail by Police d Gramam 151 CRPC PS Kollengode Addl SI of Police Unnanchathan T.K. -

PONNANI PEPPER PROJECT History Ponnani Is Popularly Known As “The Mecca of Kerala”

PONNANI PEPPER PROJECT HISTORY Ponnani is popularly known as “the Mecca of Kerala”. As an ancient harbour city, it was a major trading hub in the Malabar region, the northernmost end of the state. There are many tales that try to explain how the place got its name. According to one, the prominent Brahmin family of Azhvancherry Thambrakkal once held sway over the land. During their heydays, they offered ponnu aana [elephants made of gold] to the temples, and this gave the land the name “Ponnani”. According to another, due to trade, ponnu [gold] from the Arab lands reached India for the first time at this place, and thus caused it to be named “Ponnani”. It is believed that a place that is referred to as “Tyndis” in the Greek book titled Periplus of the Erythraean Sea is Ponnani. However historians have not been able to establish the exact location of Tyndis beyond doubt. Nor has any archaeological evidence been recovered to confirm this belief. Politically too, Ponnani had great importance in the past. The Zamorins (rulers of Calicut) considered Ponnani as their second headquarters. When Tipu Sultan invaded Kerala in 1766, Ponnani was annexed to the Mysore kingdom. Later when the British colonized the land, Ponnani came under the Bombay Province for a brief interval of time. Still later, it was annexed Malabar and was considered part of the Madras Province for one-and-a-half centuries. Until 1861, Ponnani was the headquarters of Koottanad taluk, and with the formation of the state of Kerala in 1956, it became a taluk in Palakkad district. -

A CONCISE REPORT on BIODIVERSITY LOSS DUE to 2018 FLOOD in KERALA (Impact Assessment Conducted by Kerala State Biodiversity Board)

1 A CONCISE REPORT ON BIODIVERSITY LOSS DUE TO 2018 FLOOD IN KERALA (Impact assessment conducted by Kerala State Biodiversity Board) Editors Dr. S.C. Joshi IFS (Rtd.), Dr. V. Balakrishnan, Dr. N. Preetha Editorial Board Dr. K. Satheeshkumar Sri. K.V. Govindan Dr. K.T. Chandramohanan Dr. T.S. Swapna Sri. A.K. Dharni IFS © Kerala State Biodiversity Board 2020 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, tramsmitted in any form or by any means graphics, electronic, mechanical or otherwise, without the prior writted permission of the publisher. Published By Member Secretary Kerala State Biodiversity Board ISBN: 978-81-934231-3-4 Design and Layout Dr. Baijulal B A CONCISE REPORT ON BIODIVERSITY LOSS DUE TO 2018 FLOOD IN KERALA (Impact assessment conducted by Kerala State Biodiversity Board) EdItorS Dr. S.C. Joshi IFS (Rtd.) Dr. V. Balakrishnan Dr. N. Preetha Kerala State Biodiversity Board No.30 (3)/Press/CMO/2020. 06th January, 2020. MESSAGE The Kerala State Biodiversity Board in association with the Biodiversity Management Committees - which exist in all Panchayats, Municipalities and Corporations in the State - had conducted a rapid Impact Assessment of floods and landslides on the State’s biodiversity, following the natural disaster of 2018. This assessment has laid the foundation for a recovery and ecosystem based rejuvenation process at the local level. Subsequently, as a follow up, Universities and R&D institutions have conducted 28 studies on areas requiring attention, with an emphasis on riverine rejuvenation. I am happy to note that a compilation of the key outcomes are being published. -

The Dravidian Languages

THE DRAVIDIAN LANGUAGES BHADRIRAJU KRISHNAMURTI The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 2RU, UK 40 West 20th Street, New York, NY 10011–4211, USA 477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, VIC 3207, Australia Ruiz de Alarc´on 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town 8001, South Africa http://www.cambridge.org C Bhadriraju Krishnamurti 2003 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2003 Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeface Times New Roman 9/13 pt System LATEX2ε [TB] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 0521 77111 0hardback CONTENTS List of illustrations page xi List of tables xii Preface xv Acknowledgements xviii Note on transliteration and symbols xx List of abbreviations xxiii 1 Introduction 1.1 The name Dravidian 1 1.2 Dravidians: prehistory and culture 2 1.3 The Dravidian languages as a family 16 1.4 Names of languages, geographical distribution and demographic details 19 1.5 Typological features of the Dravidian languages 27 1.6 Dravidian studies, past and present 30 1.7 Dravidian and Indo-Aryan 35 1.8 Affinity between Dravidian and languages outside India 43 2 Phonology: descriptive 2.1 Introduction 48 2.2 Vowels 49 2.3 Consonants 52 2.4 Suprasegmental features 58 2.5 Sandhi or morphophonemics 60 Appendix. Phonemic inventories of individual languages 61 3 The writing systems of the major literary languages 3.1 Origins 78 3.2 Telugu–Kannada. -

Dyron Daughrity

Hinduisms, Christian Missions, and the Tinnevelly Shanars: th A Study of Colonial Missions in 19 Century India DYRON B. DAUGHRITY, PHD Written During 5th Year, PhD Religious Studies University of Calgary Calgary, Alberta Protestant Christian missionaries first arrived in south India in 1706 when two young Germans began their work at a Danish colony on India's southeastern coast known as Tranquebar. These early missionaries, Bartholomaeus Ziegenbalg and Heinrich Pluetschau, brought with them a form of Lutheranism that emphasized personal piety and evangelistic fervour. They had little knowledge of what to expect from the peoples they were about to encounter. They were entering a foreign culture with scarcely sufficient preparation, but with the optimistic view that they would succeed in their task of bringing Christianity to the land of the “Hindoos.”1 The missionaries continued to come and by 1801, when the entire district of Tinnevelly (in south India) had been ceded to the British, there were pockets of Protestant Christianity all over the region. For the missionaries, the ultimate goal was conversion of the “heathen.” Vast resources were contributed by various missionary societies in Europe and America in order to establish churches, 1 In 2000, an important work by D. Dennis Hudson entitled Protestant Origins in India: Tamil Evangelical Christians, 1706-1835 (Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 2000) brought to light this complex and fascinating story of these early missionaries encountering for the first time an entirely new culture, language, and religion. This story sheds significant insight on the relationship between India and the West, particularly regarding religion and culture, and serves as a backdrop for the present research. -

Where the Flavours of the World Meet: Malabar As a Culinary Hotspot

UGC Approval No:40934 CASS-ISSN:2581-6403 Where The Flavours of The World Meet: CASS Malabar As A Culinary Hotspot Asha Mary Abraham Research Scholar, Department of English, University of Calicut, Kerala. Address for Correspondence: [email protected] ABSTRACT The pre-colonial Malabar was an all-encompassing geographical area that covered the entire south Indian coast sprawling between the Western Ghats and Arabian Sea, with its capital at Kozhikkode. When India was linguistically divided and Kerala was formed in 1956, the Malabar district was geographically divided further for easy administration. The modern day Malabar, comprises of Kozhikkode, Malappuram and few taluks of Kasarkod, Kannur, Wayanad, Palakkad and Thrissur. The Malappuram and Kozhikkod region is predominantly inhabited by Muslims, colloquially called as the Mappilas. The term 'Malabar' is said to have etymologically derived from the Malayalam word 'Malavaram', denoting the location by the side of the hill. The cuisine of Malabar, which is generally believed to be authentic, is in fact, a product of history and a blend of cuisines from all over the world. Delicacies from all over the world blended with the authentic recipes of Malabar, customizing itself to the local and seasonal availability of raw materials in the Malabar Coast. As an outcome of the age old maritime relations with the other countries, the influence of colonization, spice- hunting voyages and the demands of the western administrators, the cuisine of Malabar is an amalgam of Mughal (Persian), Arab, Portuguese,, British, Dutch and French cuisines. Biriyani, the most popular Malabar recipe is the product of the Arab influence. -

Analysing Lee's Hypotheses of Migration in the Context of Malabar

International Journal of Research in Geography (IJRG) Volume 4, Issue 1, 2018, PP 1-8 ISSN 2454-8685 (Online) http://dx.doi.org/10.20431/2454-8685.0401001 www.arcjournals.org Analysing Lee’s Hypotheses of Migration in the Context of Malabar Migration: A Case Study of Taliparamba Block, Kannur District Surabhi Rani 1 Dept.of Geography, Kannur University Payyanur Campus, Edat. P.O ,Payyanur, Kannur, Kerala Abstract: Human Migration is considered as one of the important demographic process which has manifold effect on the society as well as to the individuals, apart from the other population dynamics of fertility and mortality. Several approaches dealing with migration has evolved the concepts related to the push and pull factors causing migration. Malabar Migration is a historical phenomenon of internal migration, in which massive exodus took place in the vast jungles of Malabar concentrating with similar socio-cultural-economic group of people. Various factors related to social, cultural, demographical and economical aspects initiated the migration from erstwhile Travancore to erstwhile Malabar district. The present preliminary study tries to focus over such factors associated with Malabar Migration in Taliparamba block of Kannur district (Kerala).This study is based on the primary survey of the study area and further supplemented with other secondary materials. Keywords: migration, push and pull factors, Travancore, Malabar 1. INTRODUCTION Human migration is one of the few truly interdisciplinary fields of research of social processes which has widespread consequences for both, individuals and the society. It is a sort of geographical or spatial mobility of people with change in their place of residence and socio-cultural environment. -

VILLAGE STRUCTURE in NORTH KERALA Eric J

THE ECONOMIC WEEKLY February 9, 1952 VILLAGE STRUCTURE IN NORTH KERALA Eric J. Miller (The material on which this article is based, was collected during fieldwork in Malabar District and Cochin State from October 1947 to July 1949), ROFESSOR M. N. SRINIVAS the villages more scattered and iso lineal group of castes" which form, P prefaced his excellent article on lated, in contrast to the thicker set so to speak, the middle-class back ' The Social Structure of a Mysore tlement of the rice-growing areas in bone of the society. Traditionally Village," published in The Econo the south. The southern village is soldiers, and today often in govern mic Weekly of October 30, 1951, often an island " of houses and ment service, the Nayars are prima with an account of the chief types trees surrounded by a ''sea " of rily farmers. Ranking slightly above of village organization in India. paddy. In the north the paddy- Nayars are some small castes of Although the presence of caste prob fields more frequently resemble lakes temple servants. The lowest Nayar ably reduces the possible types to a or rivers—indeed they often tend sub-castes are washermen and bar finite number, local variations in the to be long narrow strips, irrigated bers for all higher groups. caste system, in the proportion of the from a central stream-, with the non-Hindu population, in economy. houses hidden among the trees on All these are caste-Hindus, and in topography, and in other factors, the surrounding slopes. from the chieftain castes down all have all contributed to produce are Sudras. -

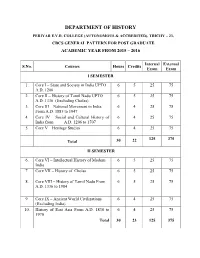

Department of History Periyar E.V.R

DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY PERIYAR E.V.R. COLLEGE (AUTONOMOUS & ACCREDITED), TRICHY – 23, CBCS GENERAL PATTERN FOR POST GRADUATE ACADEMIC YEAR FROM 2015 – 2016 Internal External S.No. Courses Hours Credits Exam Exam I SEMESTER 1. Core I – State and Society in India UPTO 6 5 25 75 A.D. 1206 2. Core II – History of Tamil Nadu UPTO 6 5 25 75 A.D. 1336 (Excluding Cholas) 3. Core III – National Movement in India 6 4 25 75 From A.D. 1885 to 1947 4. Core IV – Social and Cultural History of 6 4 25 75 India from A.D. 1206 to 1707 5. Core V – Heritage Studies 6 4 25 75 125 375 Total 30 22 II SEMESTER 6. Core VI – Intellectual History of Modern 6 5 25 75 India 7. Core VII – History of Cholas 6 5 25 75 8. Core VIII – History of Tamil Nadu From 6 5 25 75 A.D. 1336 to 1984 9. Core IX – Ancient World Civilizations 6 4 25 75 (Excluding India) 10. History of East Asia From A.D. 1830 to 6 4 25 75 1970 Total 30 23 125 375 III SEMESTER 11. Core XI – History of Political Thought 6 5 25 75 12. Core XII – Historiography 6 5 25 75 13. Core XIII – Socio - Economic and 6 5 25 75 Cultural History of India From A.D. 1707 to 1947 14. Core Based Elective - I: Contemporary 6 4 25 75 Issues in India 15. Core Based Elective - II: Dravidian 6 4 25 75 Movement Total 30 23 125 375 IV SEMESTER 16. -

Filippo Osella, University of Sussex, UK

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by SOAS Research Online Chapter 9 “I am Gulf”: The production of cosmopolitanism among the Koyas of Kozhikode, Kerala Filippo Osella, University of Sussex & Caroline Osella, SOAS, University of London Introduction: Kozhikode and the Gulf A few weeks after our arrival in Kozhikode (known as Calicut during colonial times) we were introduced to Abdulhussein (Abdulbhai), an export agent who runs a family business together with his three younger brothers. He sat behind a desk in his sparsely furnished office on Beach Road. Abdulbhai is reading a Gujarati newspaper, while one of his younger brothers is talking on the phone in Hindi to a client from Bombay. The office is quiet and so is business: our conversation is only interrupted by the occasional friend who peeps into the office to greet Abdulbhai. He begins: Business is dead, all the godowns (warehouses) along the beach are closed; all the other exporters have closed down. But at my father’s time it was all different. During the trade season, there would be hundreds of boats anchored offshore, with barges full of goods going to and fro. There were boats from Bombay, from Gujarat, from Burma and Ceylon, but most of them belonged to Arabs. Down the road there were the British warehouses, and on the other end there is the Beach Hotel, only Britishers stayed there. The beach front was busy with carts and lorries and there were hundreds of Arab sailors walking up and down. The Arab boats arrived as soon as the monsoon was over, in October, and the last left the following May, before the rain started. -

2004-05 - Term Loan

KERALA STATE BACKWARD CLASSES DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION LTD. A Govt. of Kerala Undertaking KSBCDC 2004-05 - Term Loan Name of Family Comm Gen R/ Project NMDFC Inst . Sl No. LoanNo Address Activity Sector Date Beneficiary Annual unity der U Cost Share No Income 010105768 Asha S R Keezhay Kunnathu Veedu,Irayam Codu,Cheriyakonni 0 F R Textile Business Sector 52632 44737 21/05/2004 2 010105770 Aswathy Sarath Tc/ 24/1074,Y.M.R Jn., Nandancodu,Kowdiar 0 F U Bakery Unit Business Sector 52632 44737 21/05/2004 2 010106290 Beena Kanjiramninna Veedu,Chowwera,Chowara Trivandrum 0 F R Readymade Business Sector 52632 44737 26/04/2004 2 010106299 Binu Kumar B Kunnuvila Veedu,Thozhukkal,Neyyattinkara 0 M U Dtp Centre Service Sector 52632 44737 22/04/2004 2 1 010106426 Satheesan Poovan Veedu, Tc 11/1823,Mavarthalakonam,Nalanchira 0 M U Cement Business Business Sector 52632 44737 19/04/2004 1 2 010106429 Chandrika Charuninnaveedu,Puthenkada,Thiruppuram 0 F R Copra Unit Business Sector 15789 13421 22/04/2004 1 3 010106430 Saji Shaji Bhavan,Mottamoola,Veeranakavu 0 M R Provision Store Business Sector 52632 44737 22/04/2004 1 4 010106431 Anil Kumar Varuvilakathu Pankaja Mandiram,Ooruttukala,Neyyattinkara 0 M R Timber Business Business Sector 52632 44737 22/04/2004 1 5 010106432 Satheesh Panavilacode Thekkarikath Veedu,Mullur,Mullur 0 M R Ready Made Garments Business Sector 52632 44737 22/04/2004 1 6 010106433 Raveendran R.S.Bhavan,Manthara,Perumpazhuthur 0 C M U Provision Store Business Sector 52632 44737 22/04/2004 1 010106433 Raveendran R.S.Bhavan,Manthara,Perumpazhuthur -

Carey, H. (2020). Babylon, the Bible and the Australian Aborigines. in G

Carey, H. (2020). Babylon, the Bible and the Australian Aborigines. In G. Atkins, S. Das, & B. Murray (Eds.), Chosen Peoples: The Bible, Race, and Nation in the Long Nineteenth Century (pp. 55-72). (Studies in Imperialism). Manchester University Press. Peer reviewed version Link to publication record in Explore Bristol Research PDF-document This is the author accepted manuscript (AAM). The final published version (version of record) is available online via Manchester University Press at https://manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk/9781526143068/ . Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher University of Bristol - Explore Bristol Research General rights This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the reference above. Full terms of use are available: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/red/research-policy/pure/user-guides/ebr-terms/ Part I: Peoples and Lands Babylon, the Bible and the Australian Aborigines Hilary M. Carey [God] hath made of one blood all nations of men for to dwell on all the face of the earth, and hath determined the times before appointed, and the bounds of their habitation (Acts 17:26. KJV) 'One Blood': John Fraser and the Origins of the Aborigines In 1892 Dr John Fraser (1834-1904), a schoolteacher from Maitland, New South Wales, published An Australian Language, a work commissioned by the government of New South Wales for display in Chicago at the World's Columbian Exposition (1893). 1 Fraser's edition was just one of a range of exhibits selected to represent the products, industries and native cultures of the colony to the eyes of the world.2 But it was much more than a showpiece or a simple re-printing of the collected works of Lancelot Threlkeld (1788-1859), the 1 John Fraser, ed.