Jird Issue 7 Svh 08 15 11 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Religion, Ethics, and Poetics in a Tamil Literary Tradition

Tacit Tirukku#a#: Religion, Ethics, and Poetics in a Tamil Literary Tradition The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Smith, Jason William. 2020. Tacit Tirukku#a#: Religion, Ethics, and Poetics in a Tamil Literary Tradition. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard Divinity School. Citable link https://nrs.harvard.edu/URN-3:HUL.INSTREPOS:37364524 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA ! ! ! ! ! !"#$%&!"#$%%$&'('& ()*$+$,-.&/%0$#1.&"-2&3,)%$#1&$-&"&!"4$*&5$%)6"67&!6"2$%$,-& ! ! "!#$%%&'()($*+!,'&%&+(&#! -.! /)%*+!0$11$)2!32$(4! (*! 54&!6)781(.!*9!:)';)'#!<$;$+$(.!374**1! $+!,)'($)1!9819$112&+(!*9!(4&!'&=8$'&2&+(%! 9*'!(4&!#&>'&&!*9! <*7(*'!*9!54&*1*>.! $+!(4&!%8-?&7(!*9! 54&!3(8#.!*9!@&1$>$*+! :)';)'#!A+$;&'%$(.! B)2-'$#>&C!D)%%)748%&((%! ",'$1!EFEF! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! G!EFEF!/)%*+!0$11$)2!32$(4! "11!'$>4(%!'&%&';&#H! ! ! ! ! ! <$%%&'()($*+!"#;$%*'I!J'*9&%%*'!6')+7$%!KH!B1**+&.!! ! ! !!/)%*+!0$11$)2!32$(4! ! !"#$%&!"#$%%$&'('&()*$+$,-.&/%0$#1.&"-2&3,)%$#1&$-&"&!"4$*&5$%)6"67&!6"2$%$,-! ! "-%(')7(! ! ! 54$%!#$%%&'()($*+!&L)2$+&%!(4&!!"#$%%$&'(C!)!,*&2!7*2,*%&#!$+!5)2$1!)'*8+#!(4&!9$9(4! 7&+(8'.!BHMH!(4)(!$%!(*#).!)(('$-8(&#!(*!)+!)8(4*'!+)2&#!5$'8;)NN8;)'H!54&!,*&2!7*+%$%(%!*9!OCPPF! ;&'%&%!)'')+>&#!$+(*!OPP!74),(&'%!*9!(&+!;&'%&%!&)74C!Q4$74!)'&!(4&+!#$;$#&#!$+(*!(4'&&!(4&2)($7! -

The HARVEST FIELD

The HARVEST FIELD AUGUST, 189 7. ORIGINAL ARTICLES. A PLEASANT EPISODE. THE SNAKE-BITTEN HINDU’S GBATITUDE. BY THE EEV. JACOB CHAMBERLAIN, M.D. A M up on a little mountain in our mission district fifteen miles from Madanapalle. It stands 1,750 feet above the Madanapalle plain, and is, in the hot season, some ten degrees cooler. I have built here a little “ Hermitage” to which I can come for quiet literary work. The brain works more satisfactorily andrapidly with the lower temperature, and with the absence of the continual interruptions, to which the missionary at his own station is perpetually subject. Driving out to the foot of the mountain very early Monday morning, and climbing up the rough crooked path to the summit soon after sunrise, I can have five clear days with my aman uensis for my work in helping to prepare Telugu Christian literature for the growing native church, and go down „again Friday evening to have Saturday and Sunday at my station for other duties. Thus I am up here n o w ; but my usual isolation was interrupted one day last week by a very pleasing incident. 282 A PLEASANT EPISODE. I was sitting at my desk writing and glancing out upon the moun tain scenery, when, in the wide open doorway, a figure appeared, and looking up, I saw a man from one of our native Christian villages ten miles beyond this, who, with salaams and enquiries for my health, told me that he had come as the escort of a well-to-do high-caste Telugu landholder, who lived in the caste village adjacent to theirs, and who had come up to render his thanks to me for saving his life when he was a lad and had been bitten by a deadly serpent: would I be pleased to give him audience ? He was waiting in the adjoining clump of trees to know whether I could receive him now. -

The Dravidian Languages

THE DRAVIDIAN LANGUAGES BHADRIRAJU KRISHNAMURTI The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 2RU, UK 40 West 20th Street, New York, NY 10011–4211, USA 477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, VIC 3207, Australia Ruiz de Alarc´on 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town 8001, South Africa http://www.cambridge.org C Bhadriraju Krishnamurti 2003 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2003 Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeface Times New Roman 9/13 pt System LATEX2ε [TB] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 0521 77111 0hardback CONTENTS List of illustrations page xi List of tables xii Preface xv Acknowledgements xviii Note on transliteration and symbols xx List of abbreviations xxiii 1 Introduction 1.1 The name Dravidian 1 1.2 Dravidians: prehistory and culture 2 1.3 The Dravidian languages as a family 16 1.4 Names of languages, geographical distribution and demographic details 19 1.5 Typological features of the Dravidian languages 27 1.6 Dravidian studies, past and present 30 1.7 Dravidian and Indo-Aryan 35 1.8 Affinity between Dravidian and languages outside India 43 2 Phonology: descriptive 2.1 Introduction 48 2.2 Vowels 49 2.3 Consonants 52 2.4 Suprasegmental features 58 2.5 Sandhi or morphophonemics 60 Appendix. Phonemic inventories of individual languages 61 3 The writing systems of the major literary languages 3.1 Origins 78 3.2 Telugu–Kannada. -

Dyron Daughrity

Hinduisms, Christian Missions, and the Tinnevelly Shanars: th A Study of Colonial Missions in 19 Century India DYRON B. DAUGHRITY, PHD Written During 5th Year, PhD Religious Studies University of Calgary Calgary, Alberta Protestant Christian missionaries first arrived in south India in 1706 when two young Germans began their work at a Danish colony on India's southeastern coast known as Tranquebar. These early missionaries, Bartholomaeus Ziegenbalg and Heinrich Pluetschau, brought with them a form of Lutheranism that emphasized personal piety and evangelistic fervour. They had little knowledge of what to expect from the peoples they were about to encounter. They were entering a foreign culture with scarcely sufficient preparation, but with the optimistic view that they would succeed in their task of bringing Christianity to the land of the “Hindoos.”1 The missionaries continued to come and by 1801, when the entire district of Tinnevelly (in south India) had been ceded to the British, there were pockets of Protestant Christianity all over the region. For the missionaries, the ultimate goal was conversion of the “heathen.” Vast resources were contributed by various missionary societies in Europe and America in order to establish churches, 1 In 2000, an important work by D. Dennis Hudson entitled Protestant Origins in India: Tamil Evangelical Christians, 1706-1835 (Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 2000) brought to light this complex and fascinating story of these early missionaries encountering for the first time an entirely new culture, language, and religion. This story sheds significant insight on the relationship between India and the West, particularly regarding religion and culture, and serves as a backdrop for the present research. -

The Ideological Differences Between Moderates and Extremists in the Indian National Movement with Special Reference to Surendranath Banerjea and Lajpat Rai

1 The Ideological Differences between Moderates and Extremists in the Indian National Movement with Special Reference to Surendranath Banerjea and Lajpat Rai 1885-1919 ■by Daniel Argov Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, in the University of London* School of Oriental and African Studies* June 1964* ProQuest Number: 11010545 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11010545 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 2 ABSTRACT Surendranath Banerjea was typical of the 'moderates’ in the Indian National Congress while Lajpat Rai typified the 'extremists'* This thesis seeks to portray critical political biographies of Surendranath Banerjea and of Lajpat Rai within a general comparative study of the moderates and the extremists, in an analysis of political beliefs and modes of political action in the Indian national movement, 1883-1919* It attempts to mirror the attitude of mind of the two nationalist leaders against their respective backgrounds of thought and experience, hence events in Bengal and the Punjab loom larger than in other parts of India* "The Extremists of to-day will be Moderates to-morrow, just as the Moderates of to-day were the Extremists of yesterday.” Bal Gangadhar Tilak, 2 January 190? ABBREVIATIONS B.N.]T.R. -

Finalrevised Essays on Inequality of Opportunities and Development

Essays on Inequality of Opportunities and Development Outcomes in Indonesia Umbu Reku Raya A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University October 2019 © Copyright by Umbu Reku Raya 2019 All Rights Reserved Declaration This thesis is a thesis by compilation. It contains no material that has been presented for a degree at this or any other university. To the best of my knowledge and belief, it contains no copy or paraphrase of work published by another person, except where explicitly acknowledged. All chapters were written under the guidance of my supervisor, Professor Budy Prasetyo Resosudarmo. Chapters 1 and 5 represents work solely undertaken by myself while chapter 2 is a case study on indigenous slavery on Sumba Island, the initial plan for my thesis. Chapters 2, 3 and 4 were done in collaboration with Professor Resosudarmo and it represents 85% of my contributions. Chapter 3, presents the case study on Austronesian-Hindu caste of Bali while chapter 4 deals with Muslim-Christian inequalities of opportunities. My contributions in these chapters covers the literature review, the residential survey on Sumba Island (a joint effort with Professor Resosudarmo), data analysis, choosing the appropriate dataset, reconstructing the caste information, the composition of the chapters as well as revision post presentation was undertaken by me. The chapters on indigenous slavery and Austronesian-Hindu caste in the thesis, as well as the preliminary version of the Muslim-Christian inequalities of opportunities, have been presented in various seminars at the Australian National University and several academic conferences. These conferences include the 2nd Indonesian Regional Science Association (IRSA) International Institute Conference in Bandung Indonesia (July 2009), ADEW 2015 in Monash University, and Indonesian Regional Science Association Conference in Manado Indonesia (July 2016). -

Jird Issue 7 Svh 08 15 11 3

A forum for academic, social, and timely issues affecting religious communities around the world. The Journal of InterReligious Dialogue Issue 7 August 2011 www.irdialogue.org 1 To submit an article visit www.irdialogue.org/submissions A forum for academic, social, and timely issues affecting religious communities around the world. Editorial Board Stephanie VarnonHughes and Joshua Zaslow Stanton, Editors‐in‐Chief Aimee Upjohn Light, Executive Editor Matthew Dougherty, Publishing Editor Sophia Khan, Associate Publishing Editor Christopher Stedman, Managing Director of State of Formation Ian Burzynski, Associate Director of State of Formation Editorial Consultants Frank Fredericks, Media Consultant Marinus Iwuchukwu, Outreach Consultant Stephen Butler Murray, Managing Editor Emeritus www.irdialogue.org 2 To submit an article visit www.irdialogue.org/submissions A forum for academic, social, and timely issues affecting religious communities around the world. Board of Scholars and Practitioners Y. Alp Aslandogan, President, Institute of Interfaith Dialog Justus Baird, Director of the Center for Multifaith Education, Auburn Theological Seminary Alan Brill, Cooperman/Ross Endowed Professor in honor of Sister Rose Thering, Seton Hall University Tarunjit Singh Butalia, Chair of Interfaith Committee, World Sikh Council - America Region Reginald Broadnax, Dean of Academic Affairs, Hood Theological Seminary Thomas Cattoi, Assistant Professor of Christology and Cultures, Jesuit School of Theology at Berkeley/Graduate Theological Union Miriam Cooke, -

Department of History Periyar E.V.R

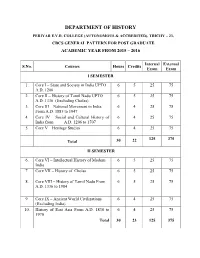

DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY PERIYAR E.V.R. COLLEGE (AUTONOMOUS & ACCREDITED), TRICHY – 23, CBCS GENERAL PATTERN FOR POST GRADUATE ACADEMIC YEAR FROM 2015 – 2016 Internal External S.No. Courses Hours Credits Exam Exam I SEMESTER 1. Core I – State and Society in India UPTO 6 5 25 75 A.D. 1206 2. Core II – History of Tamil Nadu UPTO 6 5 25 75 A.D. 1336 (Excluding Cholas) 3. Core III – National Movement in India 6 4 25 75 From A.D. 1885 to 1947 4. Core IV – Social and Cultural History of 6 4 25 75 India from A.D. 1206 to 1707 5. Core V – Heritage Studies 6 4 25 75 125 375 Total 30 22 II SEMESTER 6. Core VI – Intellectual History of Modern 6 5 25 75 India 7. Core VII – History of Cholas 6 5 25 75 8. Core VIII – History of Tamil Nadu From 6 5 25 75 A.D. 1336 to 1984 9. Core IX – Ancient World Civilizations 6 4 25 75 (Excluding India) 10. History of East Asia From A.D. 1830 to 6 4 25 75 1970 Total 30 23 125 375 III SEMESTER 11. Core XI – History of Political Thought 6 5 25 75 12. Core XII – Historiography 6 5 25 75 13. Core XIII – Socio - Economic and 6 5 25 75 Cultural History of India From A.D. 1707 to 1947 14. Core Based Elective - I: Contemporary 6 4 25 75 Issues in India 15. Core Based Elective - II: Dravidian 6 4 25 75 Movement Total 30 23 125 375 IV SEMESTER 16. -

1. Telegram to Mahomed Ali 2. Telegram to Basanti Devi

1. TELEGRAM TO MAHOMED ALI KHULNA, [June 17, 1925] REGARDING DELHI TROUBLE1 WANT SAY NOTHING ON MERITS. HAVE FULLEST FAITH YOUR INTEGRITY AND GODLINESS. MAY HE GUIDE US ALL. GANDHI From a photostat : S.N. 10644 2. TELEGRAM TO BASANTI DEVI DAS 2 [KHULNA, June 17, 1925 ] BASANTI DEVI DAS STEPASIDE DARJEELING MY HEART WITH YOU. MAY GOD BLESS YOU. EXPECT YOU BE BRAVE. BABY3 MUST NOT OVERGRIEVE. REACHING CALCUTTA EVENING. GANDHI From a photostat : S.N. 10644 3. TELEGRAM TO SATCOURIPATI ROY [KHULNA, June 17, 1925 ] UNTHINKABLE BUT GOD IS GREAT. MISSING FIRST TRAIN KEEP ESSENTIAL ENGAGEMENTS. LEAVING NOON. PRAY AWAIT ARRIVAL FINAL FUNERAL ARRANGEMENTS. THINK BODY SHOULD BE RECEIVED RUSSA ROAD UNLESS FRIENDS HAVE VALID REASONS CONTRARY. NATION’S WORK MUST NOT STOP BUT ADVANCE DOUBLE SPEED HIS GREAT SPIRIT NOBLE EXAMPLE GUIDING US. HOPE PARTY STRIF WILL BE HUSHE AND ALL WILL HEARTILY JOIN DO HONOUR 1 The reference is not clear. 2 This and the telegrams that follow were sent on the passing away of C. R. Das on June 16, at Darjeeling. Gandhiji received the news at Khulna on the following day. 3 Mona Das VOL.32 : 17 JUNE, 1925 - 24 SEPTEMBER, 1925 1 MEMORY THIS IDOL OF BENGAL AND ONE OF GREATEST OF INDIA’S SERVANTS. CANCELLING ASSAM TOUR. GANDHI From a photostat : S.N. 10644 4. TELEGRAM TO URMILA DEVI [KHULNA, June 17, 1925 ] URMILA DEVI NATURAL GRIEVE OVER DEATH LOVED ONES. BRAVE REMAIN UNPERTURBED. I WANT YOU BE BRAVE AND MAKE EVERY MAN YOUR BLOOD BROTHER. REACHING EVENING. GANDHI From a photostat : S.N. -

An Earthly Cosmology

Forum on Religion and Ecology Indigenous Traditions and Ecology Annotated Bibliography Abram, David. Becoming Animal: An Earthly Cosmology. New York and Canada: Vintage Books, 2011. As the climate veers toward catastrophe, the innumerable losses cascading through the biosphere make vividly evident the need for a metamorphosis in our relation to the living land. For too long we’ve ignored the wild intelligence of our bodies, taking our primary truths from technologies that hold the living world at a distance. Abram’s writing subverts this distance, drawing readers ever closer to their animal senses in order to explore, from within, the elemental kinship between the human body and the breathing Earth. The shape-shifting of ravens, the erotic nature of gravity, the eloquence of thunder, the pleasures of being edible: all have their place in this book. --------. The Spell of the Sensuous: Perception and Language in a More-than-Human World. New York: Vintage, 1997. Abram argues that “we are human only in contact, and conviviality, with what is not human” (p. ix). He supports this premise with empirical information, sensorial experience, philosophical reflection, and the theoretical discipline of phenomenology and draws on Merleau-Ponty’s philosophy of perception as reciprocal exchange in order to illuminate the sensuous nature of language. Additionally, he explores how Western civilization has lost this perception and provides examples of cultures in which the “landscape of language” has not been forgotten. The environmental crisis is central to Abram’s purpose and despite his critique of the consequences of a written culture, he maintains the importance of literacy and encourages the release of its true potency. -

Project Report Here

Sumba Integrated Development Revitalising traditional Marapu cultural assets in East Sumba Project Period from 15.11.2019 until 30.04.2020 Numbers at a Glance Numbers of beneficiaries reached in total :321 Female Adults age18+: 139 Male Adults age18+: 176 Youth (Male and Female) below18 : 182 Highlights of Activities Key Activity Code 1.2: Preliminary Survey and Assessment (18 November-18 December 2019) Preliminary survey and assessment of ‘at risk’ intangible cultural assets throughout the East Sumba district. Primary qualitative data about the vitality of Marapu traditional music and ritual was collected via semi-structured interviews with Marapu cultural leaders and experts. Main Achievements: We were able to open a dialogue with 15 traditional leaders of Marapu culture across 10 districts in East Sumba to classify the genres of intangible culture that existed in their district and to discuss the problems the community faced sustaining traditional culture, elicit possible solutions and communicate our objectives to determine three communities that would be the most receptive to the implementation a traditional cultural assets revitalisation program. Accomplished products: 1. Three ideal locations to implement our project were identified (Sub-district Mbatakapidu, Kamanggih and Hanggaroru) based on the criteria that traditional Marapu culture was still relatively strong in these areas, key cultural figures in these areas were already active in keeping Marapu culture vital and key local figures were committed to engage with the program and to sustain the program’s objectives into the future. 2. Thirteen genres of traditional music were identified (8 genres of vocal music 5 instrumental music genres were identified). -

The Use of Nsm and Cultural Scripts Theory in Explicating the Category of Marapu: a Traditional Animist Belief of Sumbanese

Proceedings the 5th International Conferences on Cultural Studies, Udayana University Towards the Development of Trans-Disciplinary Research Collaboration in the Era of Global Disruption Thursday August 29th, 2019 THE USE OF NSM AND CULTURAL SCRIPTS THEORY IN EXPLICATING THE CATEGORY OF MARAPU: A TRADITIONAL ANIMIST BELIEF OF SUMBANESE Yunita Reny Bani Bili ; Gracia M.N. Otta Program Studi Pendidikan Bahasa Inggris – Universitas Nusa Cendana [email protected] , [email protected] ABSTRACT As the followers of Marapu keep on believing that the source of life comes from this god, they realized that Marapu has several categories according to its function. Due to the divisions of marapu, this research explains the meaning of each category and explicated them clearly to the cultural outsiders by using the theory of cultural scripts proposed by Anna Wierzbicka, particularly natural semantic metalanguage method. Several categories were analyzed as the sample of the research, namely High Deity, the spirit of ancestor, the spirit of death, the spirit of plant and animal magical power. The result shows that each category of the Marapu has its own main roles and meaning. High deity, for example, is regarded as the creator of everything and the protector. The spirit of the ancestor, on the other hand, plays a role as the mediator between human and the highest god. The spirit of the death only functions as the companion and the keeper of the land, while the spirit of the plant and animal’s magical power functions as the mediator between Marapu and the men. Keywords: Marapu, Cultural scripts, Belief, NSM, Animist INTRODUCTION It is undeniable that each speech community has its own specific culture.