Diasporic Networks Narrate Social Suffering a Dissertation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

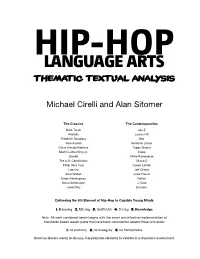

Language Arts Thematic Textual Analysis

HIP-HOPLANGUAGE ARTS THEMATIC TEXTUAL ANALYSIS Michael Cirelli and Alan Sitomer The Classics The Contemporaries Mark Twain Jay-Z Aristotle Lauryn Hill Frederick Douglass Nas Jane Austen Kendrick Lamar Oliver Wendell Holmes Tupac Shakur Martin Luther King Jr. Drake Gandhi Afrika Bambaataa The U.S. Constitution Chuck D Philip Vera Cruz Queen Latifah Lao-tzu Jeff Chang Alice Walker Lupe Fiasco Ernest Hemingway Rakim Sonia Sotomayor J. Cole Junot Díaz Eminem Delivering the 5th Element of Hip-Hop to Capable Young Minds 1. B-boying 2. MC-ing 3. Graffiti Art 4. DJ-ing 5. Knowledge Note: All work contained herein begins with the smart and effective implementation of standards-based lesson plans that have been constructed around three principles: 1. no profanity 2. no misogyny 3. no homophobia Great vocabulary words to discuss; inappropriate elements to validate in a classroom environment. HipHopLanguageArts3.indd 1 06/03/2015 15:38:37 2 | READ CLOSELY HIP-HOP INTERPRETATION GUIDE Question: Is violence ever an appropriate solution for resolving conflict? Consider the following text: from “Murder to Excellence” by Kanye West (with Jay-Z) I’m from the murder capital, where they murder for capital Heard about at least 3 killings this afternoon Lookin’ at the news like dang I was just with him after school, No shop class but half the school got a tool, And I could die any day type attitude Plus his little brother got shot reppin’ his avenue It’s time for us to stop and re-define black power 41 souls murdered in 50 hours 1. -

Juliana Geran Pilon Education

JULIANA GERAN PILON [email protected] Dr. Juliana Geran Pilon is Research Professor of Politics and Culture and Earhart Fellow at the Institute of World Politics. For the previous two years, she taught in the Political Science Department at St. Mary’s College of Maryland. From January 1991 to October 2002, she was first Director of Programs, Vice President for Programs, and finally Senior Advisor for Civil Society at the International Foundation for Election Systems (IFES), after three years at the National Forum Foundation, a non-profit institution that focused on foreign policy issues - now part of Freedom House - where she was first Executive Director and then Vice President. At NFF, she assisted in creating a network of several hundred young political activists in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union. For the past thirteen years she has also taught at Johns Hopkins University, the Institute of World Politics, George Washington University, and the Institute of World Politics. From 1981 to 1988, she was a Senior Policy Analyst at the Heritage Foundation, writing on the United Nations, Soviet active measures, terrorism, East-West trade, and other international issues. In 1991, she received an Earhart Foundation fellowship for her second book, The Bloody Flag: Post-Communist Nationalism in Eastern Europe -- Spotlight on Romania, published by Transaction, Rutgers University Press. Her autobiographical book Notes From the Other Side of Night was published by Regnery/Gateway, Inc. in 1979, and translated into Romanian in 1993, where it was published by Editura de Vest. A paperback edition appeared in the U.S. in May 1994, published by the University Press of America. -

Biblioteca Comunale Di Castelfranco Emilia

11 Giugno: Gay Pride Sii quello che sei ed esprimi quello che senti, perché a quelli che contano non importa e quelli a cui importa non contano. Dr. Seuss La bisessualità raddoppia immediatamente le tue occasioni di rimediare un appuntamento il sabato sera. Woody Allen Sabato 11 giugno 2011 l’intera comunità omosessuale italiana ed europea sarà chiamata a manifestare per i propri diritti e per l’orgoglio di essere ciò che si è. Per l' occasione, una selezione di titoli significativi dalle collezioni di libri e video della Biblioteca Federiciana e della Mediateca Montanari. Narrativa: Di Wu Ameng La manica tagliata, Sellerio, 1990 (F) Jonathan Ames Io e Henry, Einaudi, 2002 (F) Antonio Amurri Il travestito, Sugar, 1974 (F) Alberto Arbasino Fratelli d'Italia, Adelphi, 2000 (M) Reinaldo Arenas Prima che sia notte. Autobiografia, Guanda, 2000 (F) Wystan Hugh Auden Un altro tempo, Corriere della sera, 2004 (F) Wystan Hugh Auden La verità, vi prego, sull'amore, Adelphi, 1994 (F) John Banville L'intoccabile, Guanda, 1998 (F) Djuna Barnes La foresta della notte, Adelphi, 1983 (F) Giorgio Bassani Gli occhiali d'oro, Mondadori 1970, Garzanti 1986 (F) Tahar Ben Jelloun Partire, Bompiani, 2007 (F) Alan Bennett La cerimonia del massaggio, Adelphi, 2002 (F) Alan Bennett Scritto sul corpo, Adelphi, 2006 (F) Vitaliano Brancati Bell'Antonio, Bompiani, 1984 (F) William S. Burroughs Il pasto nudo, Sugarco, 1992 (F), Gruppo editoriale l'espresso SpA, 2003 (M) Aldo Busi Seminario sulla gioventu, Mondadori, 1988 (F) Mohamed Choukri Il pane nudo, Theoria, 1989 (F) Colette Il puro e l'impuro, Adelphi, 1996 (F) Andrea Demarchi I fuochi di san Giovanni, Rizzoli, 2001 (F) Louise De Salvo e Mitchell A. -

Nimble Tongues: Studies in Literary Translingualism

Purdue University Purdue e-Pubs Purdue University Press Book Previews Purdue University Press 2-2020 Nimble Tongues: Studies in Literary Translingualism Steven G. Kellman Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/purduepress_previews Part of the Language Interpretation and Translation Commons This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. NIMBLE TongueS Comparative Cultural Studies Ari Ofengenden, Series Editor The series examines how cultural practices, especially contemporary creative media, both shape and themselves are shaped by current global developments such as the digitization of culture, virtual reality, global interconnectedness, increased people flows, transhumanism, environ- mental degradation, and new forms of subjectivities. We aim to publish manuscripts that cross disciplines and national borders in order to pro- vide deep insights into these issues. Other titles in this series Imagining Afghanistan: Global Fiction and Film of the 9/11 Wars Alla Ivanchikova The Quest for Redemption: Central European Jewish Thought in Joseph Roth’s Works Rares G. Piloiu Perspectives on Science and Culture Kris Rutten, Stefaan Blancke, and Ronald Soetaert Faust Adaptations from Marlowe to Aboudoma and Markland Lorna Fitzsimmons (Ed.) Subjectivity in ʿAṭṭār, Persian Sufism, and European Mysticism Claudia Yaghoobi Reconsidering the Emergence of the Gay Novel in English and German James P. Wilper Cultural Exchanges between Brazil and France Regina R. Félix and Scott D. Juall (Eds.) Transcultural Writers and Novels in the Age of Global Mobility Arianna Dagnino NIMBLE TongueS Studies in Literary Translingualism Steven G. Kellman Purdue University Press • West Lafayette, Indiana Copyright 2020 by Purdue University. -

C. Ziari{Ti Sportivi

C. ZIARI{TI SPORTIVI ALBULESCU, VALENTIN (1925), `n special, din handbal [i fotbal. A desf\[urat o intens\ n. la Bac\u. Economist. A debutat activitate ca redactor la ziarul „Sportul” [i „Scânteia `n presa sportiv\ `n 1966, rea- Tineretului”, fiind prezent la numeroase ac]iuni inter- lizând reportaje, comentarii, `n na]ionale desf\[urate atât `n ]ar\, cât [i `n str\in\tate. principal din lumea baschetului. Dup\ 1989 a devenit redactor-[ef adjunct la ~n anii 1966-1975 a semnat `n pu- „Tineretul Liber”, apoi redactor-[ef la „Curierul blica]iile „Via]a Studen]easc\”, Na]ional”, din 1994 director general al cotidianului „Informa]ia Bucure[tiului” [i „Cronica Român\”, iar din 2001, director general al „Scânteia Tineretului”. Tot despre cotidianului „Independent”. Abandonând oarecum baschet a scris 4 c\r]i: Cu baschetbali[tii români `n problematica sportiv\, s-a lansat `n comentarii Finlanda, De la Napoli la Essen, Baschet. Mic\ enci- politice, realizând numeroase emisiuni televizate la clopedie [i Baschet românesc. Autorul f\cea o incursi- posturile „Antena 1” sau „Prima TV”. ~n perioada `n une `n evolu]ia baschetului din ]ar\ [i din str\in\tate, de care a fost reporter a scris mai multe lucr\ri, din care la `nceputuri pân\ `n acel moment. Din anul 1986 a ini- amintim: Olimpiada californian\ [i Steaua, cam- ]iat [i a realizat un program de fotbal la clubul „Sportul pioana Europei. Din anul 2001 este director general Studen]esc”, denumit Regia fotbalistic\. ~n 1991 a `n- al cotidianului „Independent”. fiin]at, `mpreun\ cu Radu Cosa[u, Gheorghe Laz\r, Radu Timofte [i Eugen Petrescu, prima revist\ de fotbal ALEXANDRESCU, TOMA (1914-1989), n. -

L'enfant De Sable'' Et ''La Nuit Sacrée'' De Tahar Ben Je

Littérature et médiation dans ”L’enfant de sable” et ”La nuit sacrée” de Tahar Ben Jelloun, ”La virgen de los sicarios” de Fernando Vallejo et ”Le cavalier et son ombre” de Boubacar Boris Diop. Yves Romuald Dissy Dissy To cite this version: Yves Romuald Dissy Dissy. Littérature et médiation dans ”L’enfant de sable” et ”La nuit sacrée” de Tahar Ben Jelloun, ”La virgen de los sicarios” de Fernando Vallejo et ”Le cavalier et son ombre” de Boubacar Boris Diop.. Littératures. Université Paris-Est, 2012. Français. NNT : 2012PEST0009. tel-00838085 HAL Id: tel-00838085 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-00838085 Submitted on 24 Jun 2013 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. LABORATOIRE LETTRES IDEES ET SAVOIRS (LIS) Spécialité : Langues et Littératures étrangères THESE DE DOCTORAT NOUVEAU REGIME Présentée et soutenue publiquement par M. Yves Romuald DISSY-DISSY Titre : LITTERATURE ET MEDIATION DANS L’ENFANT DE SABLE ET LA NUIT SACREE DE TAHAR BEN JELLOUN, LA VIRGEN DE LOS SICARIOS DE FERNANDO VALLEJO ET LE CAVALIER ET SON OMBRE DE BOUBACAR BORIS DIOP. Sous la direction de M. PAPA SAMBA DIOP, Professeur des littératures francophones et comparées Jury Examinateur : M. -

The Tallinn Diplomatic List

THE TALLINN DIPLOMATIC LIST 24 July, 2017 MINISTRY OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS OF THE REPUBLIC OF ESTONIA STATE PROTOCOL DEPARTMENT Islandi väljak 1 15049 Tallinn, Estonia Tel: (372) 637 7500 Fax: (372) 637 7099 E-mail: [email protected] Homepage: www.mfa.ee The Tallinn Diplomatic List will be updated regularly The Heads of Missions are kindly requested to communicate to the State Protocol Department all changes related to their diplomatic staff members (with spouses), contacts (address; phone and fax numbers; e-mail; address; homepage) and other relevant information. ___________________________________________________________ * – not residing in Estonia VM | VM ORDER OF PRECEDENCE AMBASSADORS 6 DIPLOMATIC MISSIONS 11 ALBANIA* 14 ALGERIA* 15 ANDORRA* 16 ANGOLA* 17 ARGENTINA* 19 ARMENIA* 20 AZERBAIJAN 21 AUSTRALIA* 22 AUSTRIA 23 BANGLADESH* 24 BELARUS 25 BELGIUM* 26 BENIN* 28 BOLIVIA* 29 BOSNIA and HERZEGOVINA* 30 BOTSWANA* 31 BRAZIL 32 BULGARIA* 33 BURKINA FASO* 34 CAMBODIA* 35 CANADA* 36 CHILE* 38 PEOPLE'S REPUBLIC OF CHINA 39 COLOMBIA* 41 CROATIA* 42 CUBA* 43 CYPRUS* 44 CZECH REPUBLIC 45 DENMARK 46 ECUADOR* 47 EGYPT* 48 EL SALVADOR* 49 ETHIOPIA* 50 FINLAND 52 FRANCE 54 ___________________________________________________________ * – not residing in Estonia VM | VM GEORGIA 56 GERMANY 57 GHANA* 59 GREECE 61 GUATEMALA* 62 GUINEA* 63 HOLY SEE* 64 HONDURAS* 65 HUNGARY* 66 ICELAND* 67 INDIA* 68 INDONESIA* 69 IRAN* 70 IRAQ* 71 IRELAND 72 ISRAEL* 73 ITALY 74 JAPAN 75 JORDAN* 76 KAZAKHSTAN* 77 REPUBLIC OF KOREA* 79 KOSOVO* 80 KUWAIT* 81 KYRGYZSTAN* 83 LAO* -

Operation Urgent Fury: High School Briefing File

OPERATION URGENT FURY: HIGH SCHOOL BRIEFING FILE PEACE THROUGH STRENGTH “ As for the enemies of freedom...they will be reminded that peace is the highest aspiration of the American people. We will negotiate for it, sacrifice for it; we will not surrender for it— now or ever.” -Ronald Reagan, 1981 TABLE OF CONTENTS COMMUNISM 2 COLD WAR TIMELINE 4 PRIMARY SOURCE DOCUMENT 6 STORIES OF SURVIVAL 8 GLOSSARY 9 COMMUNISM “The road to Hell is paved with good intentions.” - Karl Marx, Das Kapital 1 Karl Marx (1818 – 1883) was a philosopher, co-author of The Communist Manifesto, and is credited with developing the ideas and principles that led to the foundation of Communism. While he never lived to see his dream of a communist state realized, politicians such as Vladimir Lenin studied his works and formed governments like the Soviet Union, the Republic of Cuba, and Grenada. Karl Marx, 1867. Photograph by Freidrich Karl Wunder (1815-1893). Courtesy of marxists.org. In your own words, what do you think Marx meant in the quote above? ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________ The Union of Soviet Socialist Republic 1936 Constitution of the USSR Fundamental Rights and Duties of Citizens ARTICLE 123. Equality of rights of citizens of the USSR, irrespective of their nationality or race, in all spheres of economic, state, cultural, social and political life, is an indefeasible law. Any direct or indirect restriction of the rights of, or, conversely, any establishment of direct or indirect privileges for, citizens on account of their race or nationality, as well as any advocacy of racial or national exclusiveness or hatred and contempt, is punishable by law. -

A Postnational Double-Displacement: the Blurring of Anti-Roma Violence from Romania to Northern Ireland

McElroy 1 A Postnational Double-Displacement: The Blurring of Anti-Roma Violence from Romania to Northern Ireland Erin McElroy I. From Romania to Belfast and Back: A Double-Displacement of Roma in a Postnational Europe I don't mind the Poles and the Slovakians who come here. They work hard, harder than indigenous people from here, but all you see now are these Romanians begging and mooching about. We'd all be better off - them and us - if they went back to Romania or somewhere else in Europe Loyalist from South Belfast, quoted in MacDonald, 2009 And so one has to wonder: are the Gypsies really nomadic by “nature,” or have they become so because they have never been allowed to stay? Isabel Fonseca, Bury Me Standing: The Gypsies and Their Journey, 1995 On June 11, 2009, a gang of Loyalist1 youth smashed the windows and damaged the cars of members of South Belfast’s Romanian Roma2 community in an area known as the Holylands. The Holylands borders a space called the Village, a Loyalist stronghold infamous during the height of the Troubles3 for sectarian and paramilitary violence. .4 Like other members of the 1 Although not all Catholics in Northern Ireland are Republicans, and although not all Protestants in the North are Loyalists, largely, Republicans come from Catholic legacies and all Loyalists from Protestant ones. The discursive difference between each group's sovereignty is stark, painting a topography of incommensurability. Many Republicans still labor for a North freed from British governance, while Loyalists elicit that they too have existed in the North for centuries now. -

20-African-Playwrights.Pdf

1 Ama Ata Aidoo Professor Ama Ata Aidoo, née Christina Ama Aidoo (born 23 March 1940, Saltpond) is a Ghanaian author, poet, playwright and academic, who is also a former Minister of Education in the Ghana government. Life Born in Saltpond in Ghana's Central Region, she grew up in a Fante royal household, the daughter of Nana Yaw Fama, chief of Abeadzi Kyiakor, and Maame Abasema. Aidoo was sent by her father to Wesley Girls' High School in Cape Coast from 1961 to 1964. The headmistress of Wesley Girls' bought her her first typewriter. After leaving high school, she enrolled at the University of Ghana in Legon and received her Bachelor of Arts in English as well as writing her first play, The Dilemma of a Ghost, in 1964. The play was published by Longman the following year, making Aidoo the first published African woman dramatist. 2 She worked in the United States of America where she held a fellowship in creative writing at Stanford University. She also served as a research fellow at the Institute of African Studies, University of Ghana, and as a Lecturer in English at the University of Cape Coast, eventually rising there to the position of Professor. Aside from her literary career, Aidoo was appointed Minister of Education under the Provisional National Defence Council in 1982. She resigned after 18 months. She has also spent a great deal of time teaching and living abroad for months at a time. She has lived in America, Britain, Germany, and Zimbabwe. Aidoo taught various English courses at Hamilton College in Clinton, NY in the early to mid 1990s. -

Memory, Justice and Moral Cleansing

SPRING 2017 | VOL.27 | N0.2 ACTON INSTITUTE'S INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF RELIGION, ECONOMICS AND CULTURE Memory, justice and moral cleansing What are Freedom and the When our success transatlantic values? nation-state threatens our success EDITOR'S NOTE Sarah Stanley MANAGING EDITOR This spring issue of Religion & Liberty is, among other things, a reflection on the 100-year anniversary of the Bolshevik Revolution and the horrors committed by Communist regimes. For the cover story, Religion & Liberty executive editor, John Couretas, interviews Mihail Neamţu, a leading conservative in Romania. They discuss the Russian Revolution and current protests against corruption going on in Romania. A similar topic appears in Rev. Anthony Perkins’ re- view of the 2017 film Bitter Harvest. This love story is set in the Ukraine during the Holodomor, a deadly famine imposed on Ukraine by Joseph Stalin’s Soviet regime in the 1930s. Perkins addresses the signifi- cance of the Holodomor in his critique of the new movie. Romanian Orthodox hermit INTERVIEW Nicolae Steinhardt was another victim of a 07 Memory, justice and moral cleansing Communist regime. During imprisonment Coming to grips with the Russian Revolution and its legacy in a Romanian gulag, he found faith and Interview with Romanian public intellectual Mihail Neamţu even happiness. A rare excerpt in English from his “Diary of Happiness” appears in this issue. You’ve probably noticed this issue of Religion & Liberty looks very different from previous ones. As part of a wider look at international issues, this magazine has been updated and expanded to include new sections focusing on the unique chal- lenges facing Canada, Europe and the Unit- ed States. -

Printemps Du Livre De Cassis «De L'intime À L'histoire »

Le Printemps du Livre Association Loi 1901 Maison de l’Europe et de la vie Associative 4 rue Séverin Icard BP 7 13714 Cassis Cedex Tél : 06 09 73 24 50 Printemps du Livre de Cassis Avant Programme 25 Avril et 26 Avril - 2 et 3 Mai 2015 Le XXVII° Printemps du Livre de Cassis conjugue Littérature et Musique Littérature et Cinéma Littérature et Photos Littérature et Art Autour du thème : «De l’intime à l’histoire » «Nous savons que le plus intime de nos gestes contribue à faire l’histoire» Jean-Paul Sartre, Situations II Samedi 25 Avril 11h30 : Cour d’Honneur de la Mairie Inauguration par Madame le Maire du XXVII° Printemps du Livre de Cassis En présence des écrivains invités et de nombreuses personnalités 11h30/12h Jazz avec «Le quartet Tenderly» Olivier HUARD Dessins scarifiés - Peintures Aux Salles Voutées de la Mairie Du 25 Avril au 4 Mai 2015 1. Le Printemps du Livre Association Loi 1901 *Samedi 25 Avril – Dimanche 26 Avril 2015 Fondation Camargo Amphithéâtre Jérôme Hill * Samedi 25 Avril : 15h00 : Jazz avec “Le Trio Tenderly” 15h30 : «Penser et sentir» avec : Georges Vigarello Le sentiment de soi Editions du Seuil Nicolas Grimaldi Les idées en place Presses Universitaires de France 16h45 : «Des nouvelles du Petit Prince» avec : Patrick Poivre d’Arvor Courriers de nuit- La légende de Mermoz et de Saint Exupéry Editions Menguès Delphine Lacroix Le manuscrit du Petit Prince Gallimard Mohammed Aïssaoui Petit éloge des souvenirs Gallimard *En cas de mauvais temps : salle de l’Oustau Calendal Concert de jazz métissé de parfums Latins Annick TANGORRA Chanteuse, Auteur, Compositeur Le 25 Avril 2015 à L’Oustau Calendal à 21 H.