Effects of Vitamin E on Stroke: a Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis and Trial Sequential Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

8 December 2004 (Revised 10 January 2005) Topic: Unicode Technical Meeting #101, 15 -18 November 2004, Cupertino, California

To: LSA and UC Berkeley Communities From: Deborah Anderson, UCB representative and LSA liaison Date: 8 December 2004 (revised 10 January 2005) Topic: Unicode Technical Meeting #101, 15 -18 November 2004, Cupertino, California As the UC Berkeley representative and LSA liaison, I am most interested in the proposals for new characters and scripts that were discussed at the UTC, so these topics are the focus of this report. For the full minutes, readers should consult the "Unicode Technical Committee Minutes" web page (http://www.unicode.org/consortum/utc-minutes.html), where the minutes from this meeting will be posted several weeks hence. I. Proposals for New Scripts and Additional Characters A summary of the proposals and the UTC's decisions are listed below. As the proposals discussed below are made public, I will post the URLs on the SEI web page (www.linguistics.berkeley.edu/sei). A. Linguistics Characters Lorna Priest of SIL International submitted three proposals for additional linguistics characters. Most of the characters proposed are used in the orthographies of languages from Africa, Asia, Mexico, Central and South America. (For details on the proposed characters, with a description of their use and an image, see the appendix to this document.) Two characters from these proposals were not approved by the UTC because there are already characters encoded that are very similar. The evidence did not adequately demonstrate that the proposed characters are used distinctively. The two problematical proposed characters were: the modifier straight letter apostrophe (used for a glottal stop, similar to ' APOSTROPHE U+0027) and the Latin small "at" sign (used for Arabic loanwords in an orthography for the Koalib language from the Sudan, similar to @ COMMERCIAL AT U+0040). -

5892 Cisco Category: Standards Track August 2010 ISSN: 2070-1721

Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) P. Faltstrom, Ed. Request for Comments: 5892 Cisco Category: Standards Track August 2010 ISSN: 2070-1721 The Unicode Code Points and Internationalized Domain Names for Applications (IDNA) Abstract This document specifies rules for deciding whether a code point, considered in isolation or in context, is a candidate for inclusion in an Internationalized Domain Name (IDN). It is part of the specification of Internationalizing Domain Names in Applications 2008 (IDNA2008). Status of This Memo This is an Internet Standards Track document. This document is a product of the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF). It represents the consensus of the IETF community. It has received public review and has been approved for publication by the Internet Engineering Steering Group (IESG). Further information on Internet Standards is available in Section 2 of RFC 5741. Information about the current status of this document, any errata, and how to provide feedback on it may be obtained at http://www.rfc-editor.org/info/rfc5892. Copyright Notice Copyright (c) 2010 IETF Trust and the persons identified as the document authors. All rights reserved. This document is subject to BCP 78 and the IETF Trust's Legal Provisions Relating to IETF Documents (http://trustee.ietf.org/license-info) in effect on the date of publication of this document. Please review these documents carefully, as they describe your rights and restrictions with respect to this document. Code Components extracted from this document must include Simplified BSD License text as described in Section 4.e of the Trust Legal Provisions and are provided without warranty as described in the Simplified BSD License. -

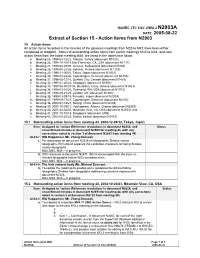

Action Items from N2903 15 Action Items All Action Items Recorded in the Minutes of the Previous Meetings from M25 to M42 Have Been Either Completed Or Dropped

ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2 N2903A DATE: 2005-08-22 Extract of Section 15 - Action Items from N2903 15 Action items All action items recorded in the minutes of the previous meetings from M25 to M42 have been either completed or dropped. Status of outstanding action items from earlier meetings M43 to M44, and new action items from the latest meeting M45, are listed in the tables that follow. a. Meeting 25, 1994-04-18/22, Antalya, Turkey (document N1033) b. Meeting 26, 1994-10-10/14,San Francisco, CA, USA (document N1117) c. Meeting 27, 1995-04-03/07, Geneva, Switzerland (document N1203) d. Meeting 28, 1995-06-22/26, Helsinki, Finland (document N 1253) e. Meeting 29, 1995-11-06/10, Tokyo, Japan (document N1303) f. Meeting 30, 1996-04-22/26, Copenhagen, Denmark (document N1353) g. Meeting 31, 1996-08-12/16, Québec City, Canada (document N1453) h. Meeting 32, 1997-01-20/24, Singapore (document N1503) i. Meeting 33, 1997-06-30/07-04, Heraklion, Crete, Greece (document N1603) j. Meeting 34, 1998-03-16/20, Redmond, WA, USA (document N1703) k. Meeting 35, 1998-09-21/25, London, UK (document N1903) l. Meeting 36, 1999-03-09/15, Fukuoka, Japan (document N2003) m. Meeting 37, 1999-09-17/21, Copenhagen, Denmark (document N2103) n. Meeting 38, 2000-07-18/21, Beijing, China (document N2203) o. Meeting 39, 2000-10-08/11, Vouliagmeni, Athens, Greece (document N2253) p. Meeting 40, 2001-04-02/05, Mountain View, CA, USA (document N2353), and q. Meeting 41, 2001-10-15/18, Singapore (document 2403) r. -

Unicode Alphabets for L ATEX

Unicode Alphabets for LATEX Specimen Mikkel Eide Eriksen March 11, 2020 2 Contents MUFI 5 SIL 21 TITUS 29 UNZ 117 3 4 CONTENTS MUFI Using the font PalemonasMUFI(0) from http://mufi.info/. Code MUFI Point Glyph Entity Name Unicode Name E262 � OEligogon LATIN CAPITAL LIGATURE OE WITH OGONEK E268 � Pdblac LATIN CAPITAL LETTER P WITH DOUBLE ACUTE E34E � Vvertline LATIN CAPITAL LETTER V WITH VERTICAL LINE ABOVE E662 � oeligogon LATIN SMALL LIGATURE OE WITH OGONEK E668 � pdblac LATIN SMALL LETTER P WITH DOUBLE ACUTE E74F � vvertline LATIN SMALL LETTER V WITH VERTICAL LINE ABOVE E8A1 � idblstrok LATIN SMALL LETTER I WITH TWO STROKES E8A2 � jdblstrok LATIN SMALL LETTER J WITH TWO STROKES E8A3 � autem LATIN ABBREVIATION SIGN AUTEM E8BB � vslashura LATIN SMALL LETTER V WITH SHORT SLASH ABOVE RIGHT E8BC � vslashuradbl LATIN SMALL LETTER V WITH TWO SHORT SLASHES ABOVE RIGHT E8C1 � thornrarmlig LATIN SMALL LETTER THORN LIGATED WITH ARM OF LATIN SMALL LETTER R E8C2 � Hrarmlig LATIN CAPITAL LETTER H LIGATED WITH ARM OF LATIN SMALL LETTER R E8C3 � hrarmlig LATIN SMALL LETTER H LIGATED WITH ARM OF LATIN SMALL LETTER R E8C5 � krarmlig LATIN SMALL LETTER K LIGATED WITH ARM OF LATIN SMALL LETTER R E8C6 UU UUlig LATIN CAPITAL LIGATURE UU E8C7 uu uulig LATIN SMALL LIGATURE UU E8C8 UE UElig LATIN CAPITAL LIGATURE UE E8C9 ue uelig LATIN SMALL LIGATURE UE E8CE � xslashlradbl LATIN SMALL LETTER X WITH TWO SHORT SLASHES BELOW RIGHT E8D1 æ̊ aeligring LATIN SMALL LETTER AE WITH RING ABOVE E8D3 ǽ̨ aeligogonacute LATIN SMALL LETTER AE WITH OGONEK AND ACUTE 5 6 CONTENTS -

1 Symbols (2286)

1 Symbols (2286) USV Symbol Macro(s) Description 0009 \textHT <control> 000A \textLF <control> 000D \textCR <control> 0022 ” \textquotedbl QUOTATION MARK 0023 # \texthash NUMBER SIGN \textnumbersign 0024 $ \textdollar DOLLAR SIGN 0025 % \textpercent PERCENT SIGN 0026 & \textampersand AMPERSAND 0027 ’ \textquotesingle APOSTROPHE 0028 ( \textparenleft LEFT PARENTHESIS 0029 ) \textparenright RIGHT PARENTHESIS 002A * \textasteriskcentered ASTERISK 002B + \textMVPlus PLUS SIGN 002C , \textMVComma COMMA 002D - \textMVMinus HYPHEN-MINUS 002E . \textMVPeriod FULL STOP 002F / \textMVDivision SOLIDUS 0030 0 \textMVZero DIGIT ZERO 0031 1 \textMVOne DIGIT ONE 0032 2 \textMVTwo DIGIT TWO 0033 3 \textMVThree DIGIT THREE 0034 4 \textMVFour DIGIT FOUR 0035 5 \textMVFive DIGIT FIVE 0036 6 \textMVSix DIGIT SIX 0037 7 \textMVSeven DIGIT SEVEN 0038 8 \textMVEight DIGIT EIGHT 0039 9 \textMVNine DIGIT NINE 003C < \textless LESS-THAN SIGN 003D = \textequals EQUALS SIGN 003E > \textgreater GREATER-THAN SIGN 0040 @ \textMVAt COMMERCIAL AT 005C \ \textbackslash REVERSE SOLIDUS 005E ^ \textasciicircum CIRCUMFLEX ACCENT 005F _ \textunderscore LOW LINE 0060 ‘ \textasciigrave GRAVE ACCENT 0067 g \textg LATIN SMALL LETTER G 007B { \textbraceleft LEFT CURLY BRACKET 007C | \textbar VERTICAL LINE 007D } \textbraceright RIGHT CURLY BRACKET 007E ~ \textasciitilde TILDE 00A0 \nobreakspace NO-BREAK SPACE 00A1 ¡ \textexclamdown INVERTED EXCLAMATION MARK 00A2 ¢ \textcent CENT SIGN 00A3 £ \textsterling POUND SIGN 00A4 ¤ \textcurrency CURRENCY SIGN 00A5 ¥ \textyen YEN SIGN 00A6 -

MSR-4: Annotated Repertoire Tables, Non-CJK

Maximal Starting Repertoire - MSR-4 Annotated Repertoire Tables, Non-CJK Integration Panel Date: 2019-01-25 How to read this file: This file shows all non-CJK characters that are included in the MSR-4 with a yellow background. The set of these code points matches the repertoire specified in the XML format of the MSR. Where present, annotations on individual code points indicate some or all of the languages a code point is used for. This file lists only those Unicode blocks containing non-CJK code points included in the MSR. Code points listed in this document, which are PVALID in IDNA2008 but excluded from the MSR for various reasons are shown with pinkish annotations indicating the primary rationale for excluding the code points, together with other information about usage background, where present. Code points shown with a white background are not PVALID in IDNA2008. Repertoire corresponding to the CJK Unified Ideographs: Main (4E00-9FFF), Extension-A (3400-4DBF), Extension B (20000- 2A6DF), and Hangul Syllables (AC00-D7A3) are included in separate files. For links to these files see "Maximal Starting Repertoire - MSR-4: Overview and Rationale". How the repertoire was chosen: This file only provides a brief categorization of code points that are PVALID in IDNA2008 but excluded from the MSR. For a complete discussion of the principles and guidelines followed by the Integration Panel in creating the MSR, as well as links to the other files, please see “Maximal Starting Repertoire - MSR-4: Overview and Rationale”. Brief description of exclusion -

Latin Extended-B Range: 0180–024F

Latin Extended-B Range: 0180–024F This file contains an excerpt from the character code tables and list of character names for The Unicode Standard, Version 14.0 This file may be changed at any time without notice to reflect errata or other updates to the Unicode Standard. See https://www.unicode.org/errata/ for an up-to-date list of errata. See https://www.unicode.org/charts/ for access to a complete list of the latest character code charts. See https://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/Unicode-14.0/ for charts showing only the characters added in Unicode 14.0. See https://www.unicode.org/Public/14.0.0/charts/ for a complete archived file of character code charts for Unicode 14.0. Disclaimer These charts are provided as the online reference to the character contents of the Unicode Standard, Version 14.0 but do not provide all the information needed to fully support individual scripts using the Unicode Standard. For a complete understanding of the use of the characters contained in this file, please consult the appropriate sections of The Unicode Standard, Version 14.0, online at https://www.unicode.org/versions/Unicode14.0.0/, as well as Unicode Standard Annexes #9, #11, #14, #15, #24, #29, #31, #34, #38, #41, #42, #44, #45, and #50, the other Unicode Technical Reports and Standards, and the Unicode Character Database, which are available online. See https://www.unicode.org/ucd/ and https://www.unicode.org/reports/ A thorough understanding of the information contained in these additional sources is required for a successful implementation. -

Homographs and Global Domain Name Watch Homographs 2019

Homographs and Global Domain Name Watch The HOMOGRAPH component added to the Global Domain Name Watch will capture a registered Domain if any of the roman characters (ascii characters) of the BRAND in question are replaced by a homograph character (a non-ascii character that looks like the ascii character) including accented letters, based on a pre-defined list. The domain registration is in effect an IDN Registration but is included and captured as part of a our standard Global Domain Name Watch service if the Homograph Component is requested. The configuration is limited to the known possible replacements identified in the list below. The fee is an additional $50 added to the price of the Domain Name Watch. Homographs 2019 Local Language & Letters Language Cyrillic Small Letter Ze з Latin Small Letter Yogh ȝ Latin Small Letter Reversed Open E ɜ Latin Small Letter Ezh ʒ Latin Small Letter Tone Five ƽ Cyrillic Small Letter Be б Digit Four 4 Latin Small Letter D with top bar ƌ Latin Small Letter Alpha ɑ Greek Small Letter Alpha α Cyrillic Small Letter A а Cyrillic Small Letter De д Latin Small Letter A with acute á Latin Small Letter A with circumflex â Latin Small Letter A with tilde ã Latin Small Letter A with diaeresis ä Latin Small Letter A with ring above å Latin Small Letter A with macron ā Latin Small Letter A with breve ă Latin Small Letter A with ogonek ą Latin Small Letter A with caron ǎ Latin Small Letter A with diaeresis and ǟ macron Latin Small Letter A with dot above and ǡ macron Latin Small Letter A with ring above and ǻ -

Doulos SIL Font 2006-01-31 Page 1 of 27

Doulos SIL Font 2006-01-31 Page 1 of 27 Doulos SIL Font NRSI staff, SIL Non-Roman Script Initiative (NRSI) 2006-01-31 Note Updates to this font and the documentation are available online at: http://scripts.sil.org/DoulosSILfont. Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................................2 Introduction to the Doulos SIL Font Package...................................................................................2 Overview of the Doulos SIL Font .......................................................................................................2 Documentation ...........................................................................................................................................3 System requirements..........................................................................................................................3 Features of the font.............................................................................................................................3 Samples ...............................................................................................................................................4 Supported character ranges ..............................................................................................................4 Private-use (PUA) characters.............................................................................................................5 Advanced typographic -

Proposal to Encode Two Latin Characters for Mazahua

Proposal to encode two Latin characters for Mazahua Denis Moyogo Jacquerye <[email protected]> 2016-01-22 (Revision of L2/14-201) Introduction The Mazahua language ( jñatrjo or jñatjo in Mazahua, ISO 639-3: maz), a Mesoamerican language recognized by a statutory law in Mexico, is written with the Latin alphabet with additional letters. One of its several Latin orthographies, the practical orthography of the SEP (Secretaría de Educación Pública de México) is used in some bilingual primary schools. The SEP orthography uses the diagonal stroke on nasalized vowels a, e, o and u. The a with stroke, e with stroke, o with stroke have already encoded characers: Ⱥ ⱥ Ɇ ɇ Ø ø. U+023A LATIN CAPITAL LETTER A WITH STROKE U+2C65 LATIN SMALL LETTER A WITH STROKE U+0246 LATIN CAPITAL LETTER E WITH STROKE U+0247 LATIN SMALL LETTER E WITH STROKE U+00D8 LATIN CAPITAL LETTER O WITH STROKE U+00F8 LATIN SMALL LETTER O WITH STROKE Some Mazahua documents currently use U ̸ (U+0055 LATIN CAPITAL LETTER U, U+0338 COMBINING LONG SOLIDUS OVERLAY) and u ̸ (U+0075 LATIN SMALL LETTER U, U+0338 COMBINING LONG SOLIDUS OVERLAY), or U+0338 combined with other base letters. However there is precedent for the encoding of letter characters with overlay stroke as single characters, for example Ⱥ ⱥ Ɇ ɇ were encoded in 2004. Proposed characters A7B8 Ꞹ LATIN CAPITAL LETTER U WITH STROKE • used in Mexico A7B9 ꞹ LATIN SMALL LETTER U WITH STROKE 1 Examples Figure 1: Example from UDHR - Mazahua Central. -

Unicode Glyph Example Languages Using the Code Point

Unicode Glyph Example EGIDS ISO Population Ref Unicode Comments languages using 639- the code point 3 (note: not an exhaustive list of languages using the code point) 00DF ß German 1 German deu 78,093,980 CLDR LATIN SMALL LETTER May only appear in the middle or at the end of a label. SHARP S IDNA version issues. 00E0 à Portuguese, 1 Portuguese por 203,352,100 CLDR LATIN SMALL LETTER French A WITH GRAVE 00E1 á Spanish 1 Spanish spa 398,931,840 CLDR LATIN SMALL LETTER A WITH ACUTE 00E2 â Portuguese, 1 Portuguese por 203,352,100 CLDR LATIN SMALL LETTER More information about circumflex use in Turkish: French, Turkish A WITH CIRCUMFLEX https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Turkish_alphabet in the Distinctive Features section. 00E3 ã Portuguese 1 Portuguese por 203,352,100 CLDR LATIN SMALL LETTER A WITH TILDE 00E4 ä German, Swedish, 1 German deu 78,093,980 CLDR LATIN SMALL LETTER Turkmen A WITH DIAERESIS 00E5 å Swedish, 1 Swedish swe 9,197,090 CLDR LATIN SMALL LETTER Norwegian A WITH RING ABOVE 00E6 æ French, Danish 1 French fra 75,916,150 CLDR LATIN SMALL LETTER AE 00E7 ç Portuguese, 1 Portuguese por 203,352,100 CLDR LATIN SMALL LETTER Catalan, Turkish C WITH CEDILLA 00E8 è French, Italian 1 French fra 75,916,150 CLDR LATIN SMALL LETTER E WITH GRAVE 00E9 é Spanish, French 1 Spanish spa 398,931,840 CLDR LATIN SMALL LETTER E WITH ACUTE 00EA ê Portuguese, 1 Portuguese por 203,352,100 CLDR LATIN SMALL LETTER French E WITH CIRCUMFLEX 00EB ë French, Dutch 1 French fra 75,916,150 CLDR LATIN SMALL LETTER E WITH DIAERESIS 00EC ì Italian 1 Italian ita 63,783,247 CLDR LATIN SMALL LETTER I WITH GRAVE 00ED í Spanish 1 Spanish spa 398,931,840 CLDR LATIN SMALL LETTER I WITH ACUTE 00EE î French, Turkish 1 French fra 75,916,150 CLDR LATIN SMALL LETTER I More information about circumflex use in Turkish: WITH CIRCUMFLEX https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Turkish_alphabet in the Distinctive Features section. -

ISO/IEC 9995-3 Revision the Revised ISO/IEC 9995-3 Is Intended to Fulfill the Following Goals: 1

Information about the Revision of ISO/IEC 9995-3 Karl Pentzlin — [email protected] — 2009-09-16 This paper is no official SC35 document. All opinions presented in this paper are the personal opinions of the author. This picture shows the common secondary group (displayed in blue) applied to a US standard keyboard. 1. Introduction The ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 35/WG 1 has decided to revise the existing ISO/IEC 9995-3 "Complementary layouts of the alphanumeric zone of the alphanumeric section" substantially. (Also, for more extensive needs, a new work item “ISO/IEC 9995-9 Multilingual, multiscript keyboard group layouts” is initiated.) The revision of ISO/IEC 9995-3 is currently to be circulated as FDIS (Final Draft International Standard) to the national bodies which will finally decide about it in the due process, which may result in a formal published standard out the first half of 2010. All information presented here, based on a FDIS (Final Draft International Standard), is final in principle, as in the FDIS state only editorial changes still can be made. Thus, while formally there is no guarantee that the standard in fact will be adopted, the information contained in the FDIS document can be considered as final and reliable, as there was no "No" vote in the previous FCD (Final Committee Draft) ballot. 2. The present edition of ISO/IEC 9995-3 The present edition of ISO/IEC 9995-3 was published in 2002 and is entitled: Information technology — Keyboard layouts for text and office systems — Part 3: Complementary layouts of the alphanumeric zone of the alphanumeric section The standard defines an "common secondary group layout", which is a mapping of characters to the unshifted and shifted positions (and, in one case, also to a third level beyond unshifted/shifted) of the 48 alphanumeric keys of a standard PC keyboard to be reached by a "group selector" (which could be a special key working similar to the "Right Alt" or"AltGr" key of some keyboards, but the exact mechanism is not subject of the standard).