Handbook of South American Indians

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reflections and Observations on Peru's Past and Present Ernesto Silva Kennesaw State University, [email protected]

Journal of Global Initiatives: Policy, Pedagogy, Perspective Volume 7 Number 2 Pervuvian Trajectories of Sociocultural Article 13 Transformation December 2013 Epilogue: Reflections and Observations on Peru's Past and Present Ernesto Silva Kennesaw State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/jgi Part of the International and Area Studies Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Silva, Ernesto (2013) "Epilogue: Reflections and Observations on Peru's Past and Present," Journal of Global Initiatives: Policy, Pedagogy, Perspective: Vol. 7 : No. 2 , Article 13. Available at: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/jgi/vol7/iss2/13 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Global Initiatives: Policy, Pedagogy, Perspective by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Emesto Silva Journal of Global Initiatives Volume 7, umber 2, 2012, pp. l83-197 Epilogue: Reflections and Observations on Peru's Past and Present Ernesto Silva 1 The aim of this essay is to provide a panoramic socio-historical overview of Peru by focusing on two periods: before and after independence from Spain. The approach emphasizes two cultural phenomena: how the indigenous peo ple related to the Conquistadors in forging a new society, as well as how im migration, particularly to Lima, has shaped contemporary Peru. This contribu tion also aims at providing a bibliographical resource to those who would like to conduct research on Peru. -

First Civilizations Cities, States, and Unequal Societies 3500 B.C.E.–500 B.C.E

c h a p t e r t h r e e First Civilizations Cities, States, and Unequal Societies 3500 B.C.E.–500 B.C.E. “Over 100 miles of wilderness, deep exploration into pristine lands, the solitude of backcountry camping, 4-4 trails, and ancient American Indian rock art and ruins. You can’t find a better way to escape civilization!”1 So goes an advertisement for a vacation in Utah’s Canyonlands National Park, one of thousands of similar attempts to lure apparently constrained, beleaguered, and “civilized” city-dwellers into the spacious freedom of the wild and the imagined simplicity of earlier times. This urge to “escape from civilization” has long been a central feature in modern life. It is a major theme in Mark Twain’s famous novel The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, in which the restless and rebellious Huck resists all efforts to “civilize” him by fleeing to the freedom of life on the river. It is a large part of the “cowboy” image in American culture, and it permeates environmentalist efforts to protect the remaining wilderness areas of the country. Nor has this impulse been limited to modern societies and the Western world. The ancient Chinese teachers of Daoism likewise urged their followers to abandon the structured and demanding world of urban and civilized life and to immerse themselves in the eternal patterns of the natural order. It is a strange paradox that we count the creation of civilization among the major achievements of humankind and yet people within these civilizations have often sought to escape the constraints, artificiality, hierarchies, and other discontents of city living. -

Climate, Agricultural Strategies, and Sustainability in the Precolumbian Andes Charles Ortloff [email protected]

Andean Past Volume 9 Article 15 11-1-2009 Climate, Agricultural Strategies, and Sustainability in the Precolumbian Andes Charles Ortloff [email protected] Michael E. Moseley University of Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/andean_past Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons, Natural Resource Economics Commons, Natural Resources Management and Policy Commons, Sustainability Commons, and the Water Resource Management Commons Recommended Citation Ortloff, Charles and Moseley, Michael E. (2009) "Climate, Agricultural Strategies, and Sustainability in the Precolumbian Andes," Andean Past: Vol. 9 , Article 15. Available at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/andean_past/vol9/iss1/15 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Andean Past by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CLIMATE, AGRICULTURAL STATEGIES, AND SUSTAINABILITY IN THE PRECOLUMBIAN ANDES CHARLES R. ORTLOFF University of Chicago and MICHAEL E. MOSELEY University of Florida INTRODUCTION allowed each society to design and manage complex water supply networks and to adapt Throughout ancient South America, mil- them as climate changed. While shifts to marine lions of hectares of abandoned farmland attest resources, pastoralism, and trade may have that much more terrain was cultivated in mitigated declines in agricultural production, precolumbian times than at present. For Peru damage to the sustainability of the main agricul- alone, the millions of hectares of abandoned tural system often led to societal changes and/or agricultural land show that in some regions 30 additional modifications to those systems. -

Inca Statehood on the Huchuy Qosqo Roads Advisor

Silva Collins, Gabriel 2019 Anthropology Thesis Title: Making the Mountains: Inca Statehood on the Huchuy Qosqo Roads Advisor: Antonia Foias Advisor is Co-author: None of the above Second Advisor: Released: release now Authenticated User Access: No Contains Copyrighted Material: No MAKING THE MOUNTAINS: Inca Statehood on the Huchuy Qosqo Roads by GABRIEL SILVA COLLINS Antonia Foias, Advisor A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts with Honors in Anthropology WILLIAMS COLLEGE Williamstown, Massachusetts May 19, 2019 Introduction Peru is famous for its Pre-Hispanic archaeological sites: places like Machu Picchu, the Nazca lines, and the city of Chan Chan. Ranging from the earliest cities in the Americas to Inca metropolises, millennia of urban human history along the Andes have left large and striking sites scattered across the country. But cities and monuments do not exist in solitude. Peru’s ancient sites are connected by a vast circulatory system of roads that connected every corner of the country, and thousands of square miles beyond its current borders. The Inca road system, or Qhapaq Ñan, is particularly famous; thousands of miles of trails linked the empire from modern- day Colombia to central Chile, crossing some of the world’s tallest mountain ranges and driest deserts. The Inca state recognized the importance of its road system, and dotted the trails with rest stops, granaries, and religious shrines. Inca roads even served directly religious purposes in pilgrimages and a system of ritual pathways that divided the empire (Ogburn 2010). This project contributes to scholarly knowledge about the Inca and Pre-Hispanic Andean civilizations by studying the roads which stitched together the Inca state. -

Conquista-Dores E Coronistas: As Primeiras Narrativas Sobre O Novo Reino De Granada

1 UNIVERSIDADE DE BRASÍLIA INSTITUTO DE CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM HISTÓRIA CONQUISTA-DORES E CORONISTAS: AS PRIMEIRAS NARRATIVAS SOBRE O NOVO REINO DE GRANADA JUAN DAVID FIGUEROA CANCINO BRASÍLIA 2016 2 JUAN DAVID FIGUEROA CANCINO CONQUISTA-DORES E CORONISTAS: AS PRIMEIRAS NARRATIVAS SOBRE O NOVO REINO DE GRANADA Tese apresentada ao Programa de Pós- graduação em História da Universidade de Brasília como requisito parcial para a obtenção do título de Doutor em História. Linha de pesquisa: História cultural, Memórias e Identidades. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Jaime de Almeida BRASÍLIA 2016 3 Às minhas avós e meus avôs, que nasceram e viveram na região dos muíscas: Maria Cecilia, Nina, Miguel Antonio e José Ignacio 4 AGRADECIMENTOS Desejo expressar minha profunda gratidão a todas as pessoas e instituições que me ajudaram de mil e uma formas a completar satisfatoriamente o doutorado: A meu orientador, o prof. Dr. Jaime de Almeida, por ter recebido com entusiasmo desde o começo a iniciativa de desenvolver minha tese sob sua orientação; pela paciência e tolerância com as mudanças do tema; pela leitura cuidadosa, os valiosos comentários e sugestões; e também porque ele e sua querida esposa Marli se esforçaram para que minha estadia no Brasil fosse o mais agradável possível, tanto no DF como em sua linda casa de Ipameri. Aos membros da banca final pelas importantes contribuições para o aprimoramento da pesquisa: os profs. Drs. Anna Herron More, Susane Rodrigues de Oliveira, José Alves de Freitas Neto e Alberto Baena Zapatero. Aos profs. Drs. Estevão Chaves de Rezende e João Paulo Garrido Pimenta pela leitura cuidadosa e as sugestões durante o exame geral de qualificação, embora as partes do trabalho que eles examinaram tenham mudado em escopo e temática. -

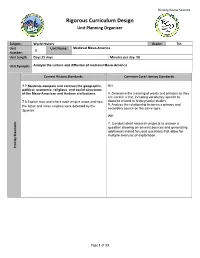

Rigorous Curriculum Design Unit Planning Organizer

History/Social Science Rigorous Curriculum Design Unit Planning Organizer Subject: World History Grade: 7th Unit Unit Name: Medieval Meso-America 3 Number: Unit Length Days:15 days Minutes per day: 50 Unit Synopsis Analyze the culture and diffusion of medieval Meso-America Current History Standards Common Core Literacy Standards 7.7 Students compare and contrast the geographic, RH political, economic, religious, and social structures of the Meso-American and Andean civilizations. 4. Determine the meaning of words and phrases as they are used in a text, including vocabulary specific to 7.3 Explain how and where each empire arose and how domains related to history/social studies the Aztec and Incan empires were defeated by the 9. Analyze the relationship between a primary and secondary source on the same topic. Spanish. WH 7. Conduct short research projects to answer a question drawing on several sources and generating additional related focused questions that allow for Standards multiple avenues of exploration. Priority Page 1 of 13 History/Social Science Common Core Literacy Standards Current History Standards RH 7.7 Students compare and contrast the geographic, political, economic, religious, and social structures 3. Identify key steps in a text’s description of a process of the Meso-American and Andean civilizations. related to history/social studies (e.g., how a bill becomes law, how interest rates are raised or lowered). Standards .1 Study the locations, landforms, and climates of 5. Describe how a text presents information (e.g., Mexico, Central America, and South America and their sequentially, comparatively, causally). effects on Mayan, Aztec, and Incan economies, trade, 6. -

BOLETIN 3087 DE REGISTROS DEL 23 JUNIO AL 29 JUNIO DE 2012 PUBLICADO 05 JULIO DE 2012 Para Los Efectos Señalados En El Artícul

BOLETIN 3087 DE REGISTROS DEL 23 JUNIO AL 29 JUNIO DE 2012 PUBLICADO 05 JULIO DE 2012 Para los efectos señalados en el artículo 47 del Código Contencioso Administrativo, se informa que: Contra los actos de inscripción en el registro mercantil que aparecen relacionados en el presente boletín proceden los recursos de reposición y de apelación. Contra el acto que niega la apelación procede el recurso de queja. El recurso de reposición deberá interponerse ante la misma Cámara de Comercio de Bogotá, para que ella confirme, aclare o revoque el respectivo acto de inscripción. El recurso de apelación deberá interponerse ante la misma Cámara de Comercio de Bogotá, para que la Superintendencia de Industria y Comercio confirme, aclare o revoque el acto de inscripción expedido por la primera entidad. El recurso de queja deberá interponerse ante la Superintendencia de Industria y Comercio, para que ella determine si es procedente o no el recurso de apelación que haya sido negado por la Cámara de Comercio de Bogotá. Los recursos de reposición y apelación deberán interponerse por escrito dentro de los cinco días hábiles siguientes a esta publicación. El recurso de queja deberá ser interpuesto por escrito dentro de los cinco días siguientes a la notificación del acto por medio del cual se resolvió negar el de apelación. Al escrito contentivo del recurso de queja deberá anexarse copia de la providencia negativa de la apelación. Los recursos deberán interponerse dentro del término legal, expresar las razones de la inconformidad, expresar el nombre y la dirección del recurrente y 1 relacionar cuando sea del caso las pruebas que pretendan hacerse valer. -

Quoted, 264 Adelman, Je

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-13328-9 - Colonialism and Postcolonial Development: Spanish America in Comparative Perspective James Mahoney Index More information Index Abad people, 106 to Canada, 251; and contrasting Abernethy, David B., 2 levels of development in interior vs. Aborigines, 236 littoral, 132; and estancias, 127–8, Acemoglu, Daron, 13–14, 17–19, 234, 146; European migration to, 131, 264–5; quoted, 264 211; and exploitation of indigenous Adelman, Jeremy, 204; quoted, 203 population, 81; exports of, 128; Africa: British colonialism in, 236–7; financial institutions in, 126;and economic and social disaster in, 237, “free trade,” 125–6; gaucho workers 257; precolonial societies, 256 in, 127; GDP per capita of, 128, African population: as cause of liberal 210–12; “golden age” in, 128, 210, colonialism, 183, 201; in colonial 211; intendant system in, 126; Argentina, 125–6, 130; in colonial investments in education in, 224;lack Brazil, 245–6; in colonial Colombia, of dominance of large estates in, 127; 107–8, 160; in colonial El Salvador, landed class of, 127; literacy and life 95; colonial exploitation of, 53;in expectancy in, 222–4; livestock colonial Mexico, 58, 60; in colonial industry of, 82, 126–7, 130, 211; Peru, 67–9, 71; in colonial Uruguay, merchants in, 82, 126–8; 80; in United States, 236;inWest nation-building myths in, 224; Indies, precolonial societies in, 77–9; 238; see also slavery problems of industrialization in, 211, Alvarado, Pedro de, 94, 97 212; reversal of development in, 212; Amaral, Samuel, quoted, -

Peoples and Civilizations of the Americas

PeoplesPeoples and and Civilizations Civilizations of of thethe Americas Americas 600600--15001500 TeotihuacanTeotihuacan TeotihuacanTeotihuacan waswas aa largelarge MesoamericanMesoamerican citycity atat thethe heightheight ofof itsits powerpower inin 450450––600600 c.ec.e.. TheThe citycity hadhad aa populationpopulation ofof 125,000125,000 toto 200,000200,000 inhabitantsinhabitants DominatedDominated byby religiousreligious structuresstructures PyramidsPyramids andand templestemples wherewhere humanhuman sacrificesacrifice waswas carriedcarried out.out. TheThe growth growth of of Teotihuacan Teotihuacan MadeMade possiblepossible byby forcedforced relocationrelocation ofof farmfarm familiesfamilies toto thethe citycity ByBy agriculturalagricultural innovationsinnovations includingincluding irrigationirrigation worksworks andand chinampaschinampas ((““floatingfloating gardensgardens””)) thatthat ThisThis increasedincreased foodfood productionproduction andand thusthus supportedsupported aa largerlarger populationpopulation ChinampasChinampas ApartmentApartment--likelike stonestone buildingsbuildings housedhoused commoners,commoners, includingincluding thethe artisansartisans whowho mademade potterypottery andand obsidianobsidian toolstools andand weaponsweapons forfor exportexport TheThe elite:elite: LivedLived inin separateseparate residentialresidential compoundscompounds ControlledControlled thethe statestate bureaucracy,bureaucracy, taxtax collection,collection, andand commerce.commerce. WhoWho controlled controlled Teotihuacan Teotihuacan -

Colombia Curriculum Guide 090916.Pmd

National Geographic describes Colombia as South America’s sleeping giant, awakening to its vast potential. “The Door of the Americas” offers guests a cornucopia of natural wonders alongside sleepy, authentic villages and vibrant, progressive cities. The diverse, tropical country of Colombia is a place where tourism is now booming, and the turmoil and unrest of guerrilla conflict are yesterday’s news. Today tourists find themselves in what seems to be the best of all destinations... panoramic beaches, jungle hiking trails, breathtaking volcanoes and waterfalls, deserts, adventure sports, unmatched flora and fauna, centuries old indigenous cultures, and an almost daily celebration of food, fashion and festivals. The warm temperatures of the lowlands contrast with the cool of the highlands and the freezing nights of the upper Andes. Colombia is as rich in both nature and natural resources as any place in the world. It passionately protects its unmatched wildlife, while warmly sharing its coffee, its emeralds, and its happiness with the world. It boasts as many animal species as any country on Earth, hosting more than 1,889 species of birds, 763 species of amphibians, 479 species of mammals, 571 species of reptiles, 3,533 species of fish, and a mind-blowing 30,436 species of plants. Yet Colombia is so much more than jaguars, sombreros and the legend of El Dorado. A TIME magazine cover story properly noted “The Colombian Comeback” by explaining its rise “from nearly failed state to emerging global player in less than a decade.” It is respected as “The Fashion Capital of Latin America,” “The Salsa Capital of the World,” the host of the world’s largest theater festival and the home of the world’s second largest carnival. -

Mesoamerican & Andean Civilizations

10/25/2011 Mesoamerican & Andean Civilizations MOST LIKELY THEORY First Americans originated in Gobi Desert Some migrated to Siberia around 15,000 years ago Crossed Bering Strait in Alaska Land bridge probably existed at the time Gradually dispersed throughout North and South America 1 10/25/2011 MESOAMERICA Mesoamerica In what is now southern Mexico and Central America Rain forests cover the region Fertile soil made this a good area for farming People first appeared in this area around 12,000 BC Maize (corn) being grown around 3500 BC 2 10/25/2011 The Olmec First urban civilization formed in Mesoamerica – around 1200 BC Built the first pyramids in the Americas Developed the first writing system in the Americas Traded with others from far away Civilization ended around 400 BC OLMEC ACHIEVEMENTS Talented engineers and architects Built sewer system Built pyramids and palaces from stone Also carved giant stone heads Largest is 9 feet tall and weighs 15 tons No one knows their exact function Writing system and a system to record calendar dates 3 10/25/2011 OLMEC RELIGION Polytheistic Most important god portrayed as half man/half jaguar Believed that certain people could turn into jaguars at will Variation of the “were-wolf” myth TEOTIHUACÁN Olmec civilization faded around 900 BCE. Teotihuacán 200-700 AD Giant city containing 200,000 people Two giant pyramids Pyramid of the Sun Pyramid of the Moon Hundreds of other buildings 4 10/25/2011 L a n d s o f t h e M a y a n s The Yucatan Peninsula 5 10/25/2011 Ch i c h e n - I t z a - P y r a mi -

Organizaciones Sociales Y De Derechos Humanos Piden

ORGANIZACIONES SOCIALES Y DE DERECHOS HUMANOS PIDEN FRENAR LA MILITARIZACION DE LA PROTESTA SOCIAL Y EL RESTABLECIMIENTO DE GARANTIAS Y LIBERTADES PARA LA MOVILIZACION CIUDADANÍA EN COLOMBIA Mayo 4 de 2020 Varios días después de las numerosas protestas sociales, el gobierno del Presidente Iván Duque se decidió a escuchar el clamor popular de retirar la regresiva y nefasta propuesta de Reforma Tributaria, que de manera indolente pretendía estrangular aún más las deterioradas condiciones de vida de la población, produto de las malas políticas para manejasr la pandemia. Sin embargo, su empeño por imponerla por la fuerza en contra de una mayoría de la población, desató una represión violenta sobre la ciudadanía y una negación flagrante de las elementales garantías en un Estado de Derecho para el ejercicio de la movilización, la protesta y la participación ciudadana en los asuntos que los afectan. Luego de seis días de intensas movilizaciones, la represión que se desató contra las personas, que por millones se lanzaron a las calles para impedir semejante atropello contra las clases medias, pobres y asalariadas, se saldó con la vida de 18 personas asesinadas, 305 heridas, 23 con mutilación o lesiones oculares, 11 casos de violencia sexual y violencias basadas en género, al menos 988 detenidos, 8 allanamientos fueron declarados ilegales, 398 denuncias por abusos de poder, autoridad, agresiones y violencia policial, y 47 agresiones intencionales a defensores/as de derechos humanos o reporteros independientes que denunciaban o trataban de poner fin a estos atropellos(Campaña Defender la Libertad Asunto de Todas - 4 mayo 2021. https://defenderlalibertad.com/situacion-de-derechos-humanos-en-colombia-paronacional/ Sin embargo, la decisión del gobierno de Duque de sacar el Ejército a las calles para reforzar la contención a la protesta social, añadió una nueva vulneración al orden constitucional y legal, generando además, mayor violencia estatal, como la registrada en la ciudada de Cali y otras ciudades del país, el día 3 de mayo.