Reflections and Observations on Peru's Past and Present Ernesto Silva Kennesaw State University, [email protected]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chinese Bondage in Peru

CHINESE BONDAGE IN PERU Stewart UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA LIBRARIES COLLEGE LIBRARV DUKE UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS CHINESE BONDAGE IN PERU Chinese Bondage IN PERU A History of the Chinese Coolie in Peru, 1849-1874 BY WATT STEWART DURHAM, NORTH CAROLINA DUKE UNIVERSITY PRESS 1951 Copyright, 195 i, by the Duke University Press PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BY THE SEEMAN PRINTERY, INC., DURHAM, N. C. ij To JORGE BASADRE Historian Scholar Friend Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from LYRASIS IVIembers and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/chinesebondageinOOstew FOREWORD THE CENTURY just passed has witnessed a great movement of the sons of China from their huge country to other portions of the globe. Hundreds of thousands have fanned out southwestward, southward, and southeastward into various parts of the Pacific world. Many thousands have moved eastward to Hawaii and be- yond to the mainland of North and South America. Other thousands have been borne to Panama and to Cuba. The movement was in part forced, or at least semi-forced. This movement was the consequence of, and it like- wise entailed, many problems of a social and economic nature, with added political aspects and implications. It was a movement of human beings which, while it has had superficial notice in various works, has not yet been ade- quately investigated. It is important enough to merit a full historical record, particularly as we are now in an era when international understanding is of such extreme mo- ment. The peoples of the world will better understand one another if the antecedents of present conditions are thoroughly and widely known. -

Outline and Chart Lago Espanol.Ala.4.4.2015

The Spanish Navigations in the SPANISH LAKE (Pacific Ocean) and their Precedents From the Discovery of the New World (Indies, later America) Spanish explorers threw themselves with “gusto” into further discoverings and expeditions. They carried in their crew not only the “conquerors” and explorers, but also priests, public administrators who would judge the area’s value for colonization, linguists, scientists, and artists. These complete set of crew members charted the coasts, the currents, the winds, the fauna and flora, to report back to the crown for future actions and references. A very important part of the Spanish explorations, is the extent and role of local peoples in Spain’s discoveries. It was the objective of the crown that friendly connections and integration be made. In fact there were “civil wars” among the crown and some “colonizers” to enforce the Laws of Indies which so specified. Today, some of this information has been lost, but most is kept in public and private Spanish Museums, Libraries, Archives and private collections not only in Spain but in the America’s, Phillipines, the Vatican, Germany, Holland, and other european countries, and of course the United States, which over its 200 year existence as a nation, also managed to collect important information of the early explorations. Following is a synopsis of the Spanish adventure in the Pacific Ocean (Lago Español) and its precedents. The Spanish Navigations in the SPANISH LAKE (Pacific Ocean) and their Precedents YEAR EXPLORER AREA EXPLORED OBSERVATIONS 1492 Cristobal -

La Moneda: Investigación Numismática Y Fuentes Archivísticas

La Moneda: Investigación numismática y fuentes archivísticas Mª Teresa Muñoz Serrulla (Coord. y Ed.) Madrid, 2012. UNIVERSIDAD COMPLUTENSE MADRID La publicación de este libro ha sido co-financiada por la Asociación de Amigos del Archivo Histórico Nacional y el Dpto. de Ciencias y Técnicas Historiográficas y de Arqueología, UCM. © De los textos sus autores. © De la presente edición, la Asociación de Amigos del Archivo Histórico Nacional. © De la presente edición, el Grupo de Investigación Numismática e Investigación Documental –Numisdoc – (Nº Ref. 941.301). © De las imágenes, sus autores o los respectivos propietarios del copyright. ISBN: 978-84-695-4325-2 Depósito Legal: M-28002-2012 Edita: Asociación de Amigos del Archivo Histórico Nacional y Dpto. de Ciencias y Técnicas Historiográficas y de Arqueología, UCM. Con la Colaboración de: La Moneda: Investigación numismática y fuentes archivísticas Mª Teresa Muñoz Serrulla (Coord. y Ed.) Madrid, 2012 Asociación de Amigos del Archivo Histórico Nacional Grupo de Investigación UCM: Numisdoc (Núm. Ref. 941.301) Dpto. de Ciencias y Técnicas Historiográficas y de Arqueología Facultad de Geografía e Historia Índice Presentación .................................................................................................................................................................... 7 La investigación numismática desde la Cátedra de “Epigrafía y Numismática” de la UCM. ............. 9 Numismatic research from the "epigraphy and numismatics" Chair of the UCM. Dra. María Ruiz Trapero Hallazgos de moneda andalusí y documentación ........................................................................................... 18 Discovery of Al-Andalus coins and documentation. Dr. Alberto J. Canto García La moneda medieval: fuentes documentales para su estudio ................................................................... 59 The medieval currency: documentary sources for research. Dr. José María de Francisco Olmos Reflexiones sobre la investigación y estudio de la moneda en la Edad Moderna ............................. -

First Civilizations Cities, States, and Unequal Societies 3500 B.C.E.–500 B.C.E

c h a p t e r t h r e e First Civilizations Cities, States, and Unequal Societies 3500 B.C.E.–500 B.C.E. “Over 100 miles of wilderness, deep exploration into pristine lands, the solitude of backcountry camping, 4-4 trails, and ancient American Indian rock art and ruins. You can’t find a better way to escape civilization!”1 So goes an advertisement for a vacation in Utah’s Canyonlands National Park, one of thousands of similar attempts to lure apparently constrained, beleaguered, and “civilized” city-dwellers into the spacious freedom of the wild and the imagined simplicity of earlier times. This urge to “escape from civilization” has long been a central feature in modern life. It is a major theme in Mark Twain’s famous novel The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, in which the restless and rebellious Huck resists all efforts to “civilize” him by fleeing to the freedom of life on the river. It is a large part of the “cowboy” image in American culture, and it permeates environmentalist efforts to protect the remaining wilderness areas of the country. Nor has this impulse been limited to modern societies and the Western world. The ancient Chinese teachers of Daoism likewise urged their followers to abandon the structured and demanding world of urban and civilized life and to immerse themselves in the eternal patterns of the natural order. It is a strange paradox that we count the creation of civilization among the major achievements of humankind and yet people within these civilizations have often sought to escape the constraints, artificiality, hierarchies, and other discontents of city living. -

Climate, Agricultural Strategies, and Sustainability in the Precolumbian Andes Charles Ortloff [email protected]

Andean Past Volume 9 Article 15 11-1-2009 Climate, Agricultural Strategies, and Sustainability in the Precolumbian Andes Charles Ortloff [email protected] Michael E. Moseley University of Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/andean_past Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons, Natural Resource Economics Commons, Natural Resources Management and Policy Commons, Sustainability Commons, and the Water Resource Management Commons Recommended Citation Ortloff, Charles and Moseley, Michael E. (2009) "Climate, Agricultural Strategies, and Sustainability in the Precolumbian Andes," Andean Past: Vol. 9 , Article 15. Available at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/andean_past/vol9/iss1/15 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Andean Past by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CLIMATE, AGRICULTURAL STATEGIES, AND SUSTAINABILITY IN THE PRECOLUMBIAN ANDES CHARLES R. ORTLOFF University of Chicago and MICHAEL E. MOSELEY University of Florida INTRODUCTION allowed each society to design and manage complex water supply networks and to adapt Throughout ancient South America, mil- them as climate changed. While shifts to marine lions of hectares of abandoned farmland attest resources, pastoralism, and trade may have that much more terrain was cultivated in mitigated declines in agricultural production, precolumbian times than at present. For Peru damage to the sustainability of the main agricul- alone, the millions of hectares of abandoned tural system often led to societal changes and/or agricultural land show that in some regions 30 additional modifications to those systems. -

The Incas.Pdf

THE INCAS THE INCAS By Franklin Pease García Yrigoyen Translated by Simeon Tegel The Incas Franklin Pease García Yrigoyen © Mariana Mould de Pease, 2011 Translated by Simeon Tegel Original title in Spanish: Los Incas Published by Fondo Editorial de la Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú, 2007, 2009, 2014, 2015 © Fondo Editorial de la Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú, 2015 Av. Universitaria 1801, Lima 32 - Perú Tel.: (51 1) 626-2650 Fax: (51 1) 626-2913 [email protected] www.pucp.edu.pe/publicaciones Design and composition: Fondo Editorial de la Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú First English Edition: January 2011 First reprint English Edition: October 2015 Print run: 1000 copies ISBN: 978-9972-42-949-1 Hecho el Depósito Legal en la Biblioteca Nacional del Perú N° 2015-13735 Registro de Proyecto Editorial: 31501361501021 Impreso en Tarea Asociación Gráfica Educativa Pasaje María Auxiliadora 156, Lima 5, Perú Contents Introduction 9 Chapter I The Andes, its History and the Incas 13 Inca History 13 The Predecessors of the Incas in the Andes 23 Chapter II The Origin of the Incas 31 The Early Organization of Cusco and the Formation of the Tawantinsuyu 38 The Inca Conquests 45 Chapter III The Inca Economy 53 Labor 64 Agriculture 66 Agricultural Technology 71 Livestock 76 Metallurgy 81 The Administration of Production 85 Storehouses 89 The Quipus 91 Chapter IV The Organization of Society 95 The Dualism 95 The Inca 100 The Cusco Elite 105 The Curaca: Ethnic Lord 109 Inca and Local Administration 112 The Population and Population -

Corruption and Anti-Corruption Agencies: Assessing Peruvian Agencies' Effectiveness

University of Central Florida STARS Honors Undergraduate Theses UCF Theses and Dissertations 2020 Corruption and Anti-corruption Agencies: Assessing Peruvian Agencies' Effectiveness Kia R. Del Solar University of Central Florida Part of the Political Science Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/honorstheses University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the UCF Theses and Dissertations at STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Undergraduate Theses by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Del Solar, Kia R., "Corruption and Anti-corruption Agencies: Assessing Peruvian Agencies' Effectiveness" (2020). Honors Undergraduate Theses. 698. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/honorstheses/698 CORRUPTION AND ANTI-CORRUPTION AGENCIES: ASSESSING PERUVIAN AGENCIES’ EFFECTIVENESS by KIA DEL SOLAR PATIÑO A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Honors in the Majors Program in Political Science in the School of Politics, Security, and International Affairs and in the Burnett Honors College at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term, 2020 Thesis Chair: Bruce Wilson, Ph.D. Abstract Corruption has gained attention around the world as a prominent issue. This is because corruption has greatly affected several countries. Following the exploration of various definitions and types of corruption, this thesis focuses on two efforts to rein in “grand corruption”, also known as executive corruption. The thesis is informed by existing theories of corruption as well as anti- corruption agencies and then situates Peru’s experience with corruption in its theoretical context and its broader Latin American context. -

Inca Statehood on the Huchuy Qosqo Roads Advisor

Silva Collins, Gabriel 2019 Anthropology Thesis Title: Making the Mountains: Inca Statehood on the Huchuy Qosqo Roads Advisor: Antonia Foias Advisor is Co-author: None of the above Second Advisor: Released: release now Authenticated User Access: No Contains Copyrighted Material: No MAKING THE MOUNTAINS: Inca Statehood on the Huchuy Qosqo Roads by GABRIEL SILVA COLLINS Antonia Foias, Advisor A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts with Honors in Anthropology WILLIAMS COLLEGE Williamstown, Massachusetts May 19, 2019 Introduction Peru is famous for its Pre-Hispanic archaeological sites: places like Machu Picchu, the Nazca lines, and the city of Chan Chan. Ranging from the earliest cities in the Americas to Inca metropolises, millennia of urban human history along the Andes have left large and striking sites scattered across the country. But cities and monuments do not exist in solitude. Peru’s ancient sites are connected by a vast circulatory system of roads that connected every corner of the country, and thousands of square miles beyond its current borders. The Inca road system, or Qhapaq Ñan, is particularly famous; thousands of miles of trails linked the empire from modern- day Colombia to central Chile, crossing some of the world’s tallest mountain ranges and driest deserts. The Inca state recognized the importance of its road system, and dotted the trails with rest stops, granaries, and religious shrines. Inca roads even served directly religious purposes in pilgrimages and a system of ritual pathways that divided the empire (Ogburn 2010). This project contributes to scholarly knowledge about the Inca and Pre-Hispanic Andean civilizations by studying the roads which stitched together the Inca state. -

View to Avoid Glare

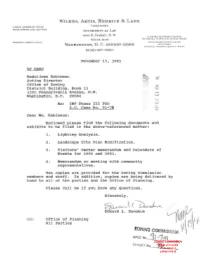

WILKES, ARTIS, HEDRICK & LANE CHARTERED CABLE ADDRESS: WILAN TELECOPIER: 202-457-7814 ATTORNEYS AT LAW 1666 STREET, K N. W. 8 BETHESDA METRO CENTER SUITE 1100 BETHESDA, MARYLAND 20814-51320 WRITER'S DIRECT DIAL, 11320 RANDOM HILLS ROAD WASHINGTON,D.C.20006-2866 SUITE 600 FAIRFAX, VIRGINIA 22000-6042 (202) 457-7800 November 13, 1991 BY HAND Madeliene Robinson Acting Director Office of Zoning District Building, Room 11 1350 Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20004 - Re: IMF Phase III PUD z.c. Case No. 91-7M Dear Ms. Robinson: Enclosed please find the following documents and exhibits to be filed in the above-referenced matter: 1. Lighting Analysis. 2. Landscape Site Plan Modification. 3. Visitors' Center memorandum and Calendars of Events for 1990 and 1991. 4. Memorandum on meeting with community representatives. Ten copies are provided for the Zoning Commission members and staff. In addition, copies are being delivered by hand to all of the parties and the Office of Planning. Please call me if you have any questions. Sincerely, cc: Office of Planning 1.' { • . I.''l i·i~,~ All Parties \ . \ \ D lONING COMMISSION \ . CASE No. __ '7 l -1 IV\ . ZONING-- COMMISSIONe il, OHiBIT No, _!jfe.District of Columbia CASE-.......___ NO.91-7 __ .,__ EXHIBIT NO.96 The Kling-Lindquist Partnership, Inc. MEMORANDUM MEMO TO: D.C. Zoning Commission FROM: Kenneth E. Yarnell, IALD Lighting Engineer The Kling-Lindquist Partnership DATE: November 8, 1991 REFERENCE: Z.C. Case No. 91-7M Phase III PUD for The International Monetary Fund - Lighting Analysis We were asked to analyze the lighting proposed for the Phase III modifications in response to questions of adequacy of light levels and safety. -

Forfoodies & Artlovers

PERU for Foodies & Art lovers If Peru is an ethnic melting pot, Lima is its port of entry. It was here that our rich Andean past first met the Spanish conquistadores, this initial “culture shock” later complemented by African, Arab, European, and Asian immigrations. Centuries of blending these different culinary expressions resulted in what Peruvian now proudly claim to be the finest cuisine in Latin America. Enrique Velasco Director COLTUR Peru Ceviche © Enrique Velasco /COLTUR Peru Lima MALI Museum © COLTUR Peru Lima Lima, the only oceanfront capital city in Aliaga family, hosts our private dinner in Latin America and gateway to Peru`s mi- this oldest colonial mansion in Lima, and llenary culture, will be the starting point perhaps all of South America. of this extraordinary voyage of artistic and culinary discovery. The Casa Aliaga was built in 1536 on a piece of land given by Francisco Pizarro to Geróni- When in Lima, it is a must to immerse your- mo de Aliaga, his main lieutenant. Maru has self in a genuine, local cevicheria lived in the house since she was 7 years old, experience. To delve deep in the understan- and knowing its past inside out, she master- ding of Peru´s trademark dish we share the fully intertwines Peruvian history with that table with re-nowned chef Diego Alcantara, of her own family. who enthusiastically recounts the history of Maru guides us on a 500-year journey back ceviche and explains how its modern ver- in time, exploring the mansion’s luxurious sion has a tremendous Japanese influence. -

Pachakutik, the Indigenous Voters, and Segmented Mobilisation

Pachakutik, the indigenous voters, and segmented mobilization strategies Diana Dávila Gordillo [email protected] Institute of Political Science, Leiden University Draft/work in progress. Comments welcome. Abstract The 2021 Ecuadorian national elections resulted in one major surprise; the small ethnic party Pachakutik almost made it to the second round. The party’s candidate came in third with less than 1% difference from the runner up. In addition, the party’s candidates to the legislature secured 27 seats (out of 137) at the National Assembly. These achievements were unexpected, particularly because Pachakutik has been defined as an ethnic party with a small indigenous captive electorate. In this paper I address the glaring question: where are all these excess votes coming from? To do so I answer two research questions: who votes for Pachakutik, and how does Pachakutik mobilize these voters? I leverage quantitative and qualitative data. I use elections data to explore Pachakutik’s electoral performance through the years and combine it with self-identification data from the 2001 and 2010 Censuses to study the indigenous voters’ voting patterns using the ecological inference technique. I find that, on average, less than 25% of all indigenous voters’ votes were cast for Pachakutik’s candidates between 2002 and 2019 at national and subnational elections. To explore Pachakutik’s candidates’ mobilization strategies, I combine two novel data sources from the 2014 mayoral elections and data from the 2021 national elections and analyze it using qualitative content analysis. I find Pachakutik’s candidates use multiple mobilization strategies to engage their voters. -

Universidad Ricardo Palma Facultad De Arquitectura Y Urbanismo

UNIVERSIDAD RICARDO PALMA FACULTAD DE ARQUITECTURA Y URBANISMO TESIS PARA OPTAR EL TÍTULO PROFESIONAL DE ARQUITECTO TÍTULO: “ESPACIO PÚBLICO PURUCHUCO Y EQUIPAMIENTO CULTURAL EN EL DISTRITO DE ATE VITARTE” AUTOR: Bach. Gaspar Arispe, Andrés Luis DIRECTOR: Arqta. Carla Rebagliatti Acuña AGOSTO DEL 2020 Lima, Perú ESPACIO PUBLICO PURUCHUCO Y EQUIPAMIENTO CULTURAL TESIS PARA OPTAR EL TITULO PROFESIONAL DE ARQUITECTO II ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Agradezco: A mis padres y hermano, que siempre estuvieron apoyándome durante mi carrera, y que siempre me motivaron a proyectarme hacia horizontes más amplios de los que ya tenía inicialmente fijados. A mi directora de tesis, La Arqta. Carla Rebagliatti, que me apoyo en el desarrollo de esta tesis con su experiencia y conocimientos. Y a mis docentes, jefes y amigos que me pudieron proporcionar apoyo de distintas formas para lograr mis objetivos. ESPACIO PUBLICO PURUCHUCO Y EQUIPAMIENTO CULTURAL TESIS PARA OPTAR EL TITULO PROFESIONAL DE ARQUITECTO III ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Tabla de Contenido 1. CAPITULO I: GENERALIDADES 1.1. Introducción……………………………………………………………………...........3 1.2. Definición del tema…………………………………………………………………....5 1.3. Planteamiento del problema…………………………………………………………...6 1.3.1. Causas determinantes………………………………………………………..…7 1.3.2. Equipamientos culturales existentes