Peoples and Civilizations of the Americas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reflections and Observations on Peru's Past and Present Ernesto Silva Kennesaw State University, [email protected]

Journal of Global Initiatives: Policy, Pedagogy, Perspective Volume 7 Number 2 Pervuvian Trajectories of Sociocultural Article 13 Transformation December 2013 Epilogue: Reflections and Observations on Peru's Past and Present Ernesto Silva Kennesaw State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/jgi Part of the International and Area Studies Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Silva, Ernesto (2013) "Epilogue: Reflections and Observations on Peru's Past and Present," Journal of Global Initiatives: Policy, Pedagogy, Perspective: Vol. 7 : No. 2 , Article 13. Available at: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/jgi/vol7/iss2/13 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Global Initiatives: Policy, Pedagogy, Perspective by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Emesto Silva Journal of Global Initiatives Volume 7, umber 2, 2012, pp. l83-197 Epilogue: Reflections and Observations on Peru's Past and Present Ernesto Silva 1 The aim of this essay is to provide a panoramic socio-historical overview of Peru by focusing on two periods: before and after independence from Spain. The approach emphasizes two cultural phenomena: how the indigenous peo ple related to the Conquistadors in forging a new society, as well as how im migration, particularly to Lima, has shaped contemporary Peru. This contribu tion also aims at providing a bibliographical resource to those who would like to conduct research on Peru. -

First Civilizations Cities, States, and Unequal Societies 3500 B.C.E.–500 B.C.E

c h a p t e r t h r e e First Civilizations Cities, States, and Unequal Societies 3500 B.C.E.–500 B.C.E. “Over 100 miles of wilderness, deep exploration into pristine lands, the solitude of backcountry camping, 4-4 trails, and ancient American Indian rock art and ruins. You can’t find a better way to escape civilization!”1 So goes an advertisement for a vacation in Utah’s Canyonlands National Park, one of thousands of similar attempts to lure apparently constrained, beleaguered, and “civilized” city-dwellers into the spacious freedom of the wild and the imagined simplicity of earlier times. This urge to “escape from civilization” has long been a central feature in modern life. It is a major theme in Mark Twain’s famous novel The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, in which the restless and rebellious Huck resists all efforts to “civilize” him by fleeing to the freedom of life on the river. It is a large part of the “cowboy” image in American culture, and it permeates environmentalist efforts to protect the remaining wilderness areas of the country. Nor has this impulse been limited to modern societies and the Western world. The ancient Chinese teachers of Daoism likewise urged their followers to abandon the structured and demanding world of urban and civilized life and to immerse themselves in the eternal patterns of the natural order. It is a strange paradox that we count the creation of civilization among the major achievements of humankind and yet people within these civilizations have often sought to escape the constraints, artificiality, hierarchies, and other discontents of city living. -

Reconsidering a Moche Site in Northern Peru

Tearing Down Old Walls in the New World: Reconsidering a Moche Site in Northern Peru Megan Proffitt The country of Peru is an interesting area, bordered by mountains on one side and the ocean on the other. This unique environment was home to numerous pre-Columbian cultures, several of which are well- known for their creativity and technological advancements. These cul- tures include such groups as the Chavin, Nasca, Inca, and Moche. The last of these, the Moche, flourished from about 0-800 AD and more or less dominated Peru’s northern coast. During the 2001 summer archaeological field season, I was granted the opportunity to travel to Peru and participate in the excavation of the Huaca de Huancaco, a Moche palace. In recent years, as Dr. Steve Bourget and his colleagues have conducted extensive research and fieldwork on the site, the cul- tural identity of its inhabitants have come into question. Although Huancaco has long been deemed a Moche site, Bourget claims that it is not. In this paper I will give a general, widely accepted description of the Moche culture and a brief history of the archaeological work that has been conducted on it. I will then discuss the site of Huancaco itself and my personal involvement with it. Finally, I will give a brief account of the data that have, and have not, been found there. This information is crucial for the necessary comparisons to other Moche sites required by Bourget’s claim that Huancaco is not a Moche site, a claim that will be explained and supported in this paper. -

Climate, Agricultural Strategies, and Sustainability in the Precolumbian Andes Charles Ortloff [email protected]

Andean Past Volume 9 Article 15 11-1-2009 Climate, Agricultural Strategies, and Sustainability in the Precolumbian Andes Charles Ortloff [email protected] Michael E. Moseley University of Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/andean_past Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons, Natural Resource Economics Commons, Natural Resources Management and Policy Commons, Sustainability Commons, and the Water Resource Management Commons Recommended Citation Ortloff, Charles and Moseley, Michael E. (2009) "Climate, Agricultural Strategies, and Sustainability in the Precolumbian Andes," Andean Past: Vol. 9 , Article 15. Available at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/andean_past/vol9/iss1/15 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Andean Past by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CLIMATE, AGRICULTURAL STATEGIES, AND SUSTAINABILITY IN THE PRECOLUMBIAN ANDES CHARLES R. ORTLOFF University of Chicago and MICHAEL E. MOSELEY University of Florida INTRODUCTION allowed each society to design and manage complex water supply networks and to adapt Throughout ancient South America, mil- them as climate changed. While shifts to marine lions of hectares of abandoned farmland attest resources, pastoralism, and trade may have that much more terrain was cultivated in mitigated declines in agricultural production, precolumbian times than at present. For Peru damage to the sustainability of the main agricul- alone, the millions of hectares of abandoned tural system often led to societal changes and/or agricultural land show that in some regions 30 additional modifications to those systems. -

The Evolution and Changes of Moche Textile Style: What Does Style Tell Us About Northern Textile Production?

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 2002 The Evolution and Changes of Moche Textile Style: What Does Style Tell Us about Northern Textile Production? María Jesús Jiménez Díaz Universidad Complutense de Madrid Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Part of the Art and Design Commons Jiménez Díaz, María Jesús, "The Evolution and Changes of Moche Textile Style: What Does Style Tell Us about Northern Textile Production?" (2002). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 403. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/403 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. THE EVOLUTION AND CHANGES OF MOCHE TEXTILE STYLE: WHAT DOES STYLE TELL US ABOUT NORTHERN TEXTILE PRODUCTION? María Jesús Jiménez Díaz Museo de América de Madrid / Universidad Complutense de Madrid Although Moche textiles form part of the legacy of one of the best known cultures of pre-Hispanic Peru, today they remain relatively unknown1. Moche culture evolved in the northern valleys of the Peruvian coast (Fig. 1) during the first 800 years after Christ (Fig. 2). They were contemporary with other cultures such us Nazca or Lima and their textiles exhibited special features that are reflected in their textile production. Previous studies of Moche textiles have been carried out by authors such as Lila O'Neale (1946, 1947), O'Neale y Kroeber (1930), William Conklin (1978) or Heiko Pruemers (1995). -

The Moche Lima Beans Recording System, Revisited

THE MOCHE LIMA BEANS RECORDING SYSTEM, REVISITED Tomi S. Melka Abstract: One matter that has raised sufficient uncertainties among scholars in the study of the Old Moche culture is a system that comprises patterned Lima beans. The marked beans, plus various associated effigies, appear painted by and large with a mixture of realism and symbolism on the surface of ceramic bottles and jugs, with many of them showing an unparalleled artistry in the great area of the South American subcontinent. A range of accounts has been offered as to what the real meaning of these items is: starting from a recrea- tional and/or a gambling game, to a divination scheme, to amulets, to an appli- cation for determining the length and order of funerary rites, to a device close to an accountancy and data storage medium, ending up with an ‘ideographic’, or even a ‘pre-alphabetic’ system. The investigation brings together structural, iconographic and cultural as- pects, and indicates that we might be dealing with an original form of mnemo- technology, contrived to solve the problems of medium and long-distance com- munication among the once thriving Moche principalities. Likewise, by review- ing the literature, by searching for new material, and exploring the structure and combinatory properties of the marked Lima beans, as well as by placing emphasis on joint scholarly efforts, may enhance the studies. Key words: ceramic vessels, communicative system, data storage and trans- mission, fine-line drawings, iconography, ‘messengers’, painted/incised Lima beans, patterns, pre-Inca Moche culture, ‘ritual runners’, tokens “Como resultado de la falta de testimonios claros, todas las explicaciones sobre este asunto parecen in- útiles; divierten a la curiosidad sin satisfacer a la razón.” [Due to a lack of clear evidence, all explana- tions on this issue would seem useless; they enter- tain the curiosity without satisfying the reason] von Hagen (1966: 157). -

Moche Culture As Political Ideology

1 HE STRUCTURALPARADOX: MOCHECULTURE AS POLITICALIDEOLOGY GarthBawden In this article I demonstrate the utility of an historical study of social change by examining the development of political authority on the Peruvian north coast during the Moche period through its symbols of power. Wetoo often equate the mater- ial record with "archaeological culture,^^assume that it reflects broad cultural realityXand interpret it by reference to gener- al evolutionary models. Here I reassess Moche society within its historic context by examining the relationship between underlying social structure and short-termprocesses that shaped Moche political formation, and reach very different con- clusions. I see the "diagnostic" Moche material recordprimarily as the symbolic manifestationof a distinctivepolitical ide- ology whose character was historically constituted in an ongoing cultural tradition.Aspiring rulers used ideology to manip- ulate culturalprinciples in their interests and thus mediate the paradox between exclusive power and holistic Andean social structure which created the dynamicfor change. A historic study allows us to identify the symbolic and ritual mechanisms that socially constituted Moche ideologyXand reveals a pattern of diversity in time and space that was the product of differ- ential choice by local rulers, a pattern that cannot be seen within a theoretical approach that emphasizes general evolution- ary or materialistfactors. En este articulo demuestro la ventaja de un estudio historico sobre la integraciony el cambio social, a traves de un examen del caracter del poder politico en la costa norte del Peru durante el periodo Moche. Con demasiadafrecuencia equiparamos el registro material con "las culturas arqueologicas "; asumimos que este refleja la realidad cultural amplia y la interpreta- mos con referencia a modelos evolutivos generales. -

Inca Statehood on the Huchuy Qosqo Roads Advisor

Silva Collins, Gabriel 2019 Anthropology Thesis Title: Making the Mountains: Inca Statehood on the Huchuy Qosqo Roads Advisor: Antonia Foias Advisor is Co-author: None of the above Second Advisor: Released: release now Authenticated User Access: No Contains Copyrighted Material: No MAKING THE MOUNTAINS: Inca Statehood on the Huchuy Qosqo Roads by GABRIEL SILVA COLLINS Antonia Foias, Advisor A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts with Honors in Anthropology WILLIAMS COLLEGE Williamstown, Massachusetts May 19, 2019 Introduction Peru is famous for its Pre-Hispanic archaeological sites: places like Machu Picchu, the Nazca lines, and the city of Chan Chan. Ranging from the earliest cities in the Americas to Inca metropolises, millennia of urban human history along the Andes have left large and striking sites scattered across the country. But cities and monuments do not exist in solitude. Peru’s ancient sites are connected by a vast circulatory system of roads that connected every corner of the country, and thousands of square miles beyond its current borders. The Inca road system, or Qhapaq Ñan, is particularly famous; thousands of miles of trails linked the empire from modern- day Colombia to central Chile, crossing some of the world’s tallest mountain ranges and driest deserts. The Inca state recognized the importance of its road system, and dotted the trails with rest stops, granaries, and religious shrines. Inca roads even served directly religious purposes in pilgrimages and a system of ritual pathways that divided the empire (Ogburn 2010). This project contributes to scholarly knowledge about the Inca and Pre-Hispanic Andean civilizations by studying the roads which stitched together the Inca state. -

Conquista-Dores E Coronistas: As Primeiras Narrativas Sobre O Novo Reino De Granada

1 UNIVERSIDADE DE BRASÍLIA INSTITUTO DE CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM HISTÓRIA CONQUISTA-DORES E CORONISTAS: AS PRIMEIRAS NARRATIVAS SOBRE O NOVO REINO DE GRANADA JUAN DAVID FIGUEROA CANCINO BRASÍLIA 2016 2 JUAN DAVID FIGUEROA CANCINO CONQUISTA-DORES E CORONISTAS: AS PRIMEIRAS NARRATIVAS SOBRE O NOVO REINO DE GRANADA Tese apresentada ao Programa de Pós- graduação em História da Universidade de Brasília como requisito parcial para a obtenção do título de Doutor em História. Linha de pesquisa: História cultural, Memórias e Identidades. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Jaime de Almeida BRASÍLIA 2016 3 Às minhas avós e meus avôs, que nasceram e viveram na região dos muíscas: Maria Cecilia, Nina, Miguel Antonio e José Ignacio 4 AGRADECIMENTOS Desejo expressar minha profunda gratidão a todas as pessoas e instituições que me ajudaram de mil e uma formas a completar satisfatoriamente o doutorado: A meu orientador, o prof. Dr. Jaime de Almeida, por ter recebido com entusiasmo desde o começo a iniciativa de desenvolver minha tese sob sua orientação; pela paciência e tolerância com as mudanças do tema; pela leitura cuidadosa, os valiosos comentários e sugestões; e também porque ele e sua querida esposa Marli se esforçaram para que minha estadia no Brasil fosse o mais agradável possível, tanto no DF como em sua linda casa de Ipameri. Aos membros da banca final pelas importantes contribuições para o aprimoramento da pesquisa: os profs. Drs. Anna Herron More, Susane Rodrigues de Oliveira, José Alves de Freitas Neto e Alberto Baena Zapatero. Aos profs. Drs. Estevão Chaves de Rezende e João Paulo Garrido Pimenta pela leitura cuidadosa e as sugestões durante o exame geral de qualificação, embora as partes do trabalho que eles examinaram tenham mudado em escopo e temática. -

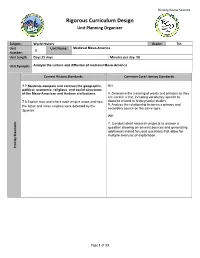

Rigorous Curriculum Design Unit Planning Organizer

History/Social Science Rigorous Curriculum Design Unit Planning Organizer Subject: World History Grade: 7th Unit Unit Name: Medieval Meso-America 3 Number: Unit Length Days:15 days Minutes per day: 50 Unit Synopsis Analyze the culture and diffusion of medieval Meso-America Current History Standards Common Core Literacy Standards 7.7 Students compare and contrast the geographic, RH political, economic, religious, and social structures of the Meso-American and Andean civilizations. 4. Determine the meaning of words and phrases as they are used in a text, including vocabulary specific to 7.3 Explain how and where each empire arose and how domains related to history/social studies the Aztec and Incan empires were defeated by the 9. Analyze the relationship between a primary and secondary source on the same topic. Spanish. WH 7. Conduct short research projects to answer a question drawing on several sources and generating additional related focused questions that allow for Standards multiple avenues of exploration. Priority Page 1 of 13 History/Social Science Common Core Literacy Standards Current History Standards RH 7.7 Students compare and contrast the geographic, political, economic, religious, and social structures 3. Identify key steps in a text’s description of a process of the Meso-American and Andean civilizations. related to history/social studies (e.g., how a bill becomes law, how interest rates are raised or lowered). Standards .1 Study the locations, landforms, and climates of 5. Describe how a text presents information (e.g., Mexico, Central America, and South America and their sequentially, comparatively, causally). effects on Mayan, Aztec, and Incan economies, trade, 6. -

EXPRESSIONS and SEVERITY of DEGENERATIVE JOINT DISEASES: a COMPARATIVE STUDY of JOINT PATHOLOGY in the LAMBAYEQUE REGION, NORTH COAST PERU By

EXPRESSIONS AND SEVERITY OF DEGENERATIVE JOINT DISEASES: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF JOINT PATHOLOGY IN THE LAMBAYEQUE REGION, NORTH COAST PERU by Michelle L. Yockey A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of George Mason University in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Anthropology Committee: ___________________________________________ Director ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ Department Chairperson ___________________________________________ Dean, College of Humanities and Social Sciences Date: _____________________________________ Spring Semester 2019 George Mason University Fairfax, VA “Expressions and Severity of Degenerative Joint Diseases: A Comparative Study of Joint Pathology in the Lambayeque Region, North Coast Peru” A Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts at George Mason University By Michelle L. Yockey Bachelor of Arts Ball State University, 2016 Director: Haagen D. Klaus Department of Sociology and Anthropology Spring Semester 2019 George Mason University Fairfax, VA DEDICATION This work is dedicated to extremely supporting and loving partner, Anthony. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank everyone who had a part in supporting me through this process. My supporting partner, Anthony, helped me immensely by talking though ideas with me and helping me through the writer’s block. My parents, Douglas and Nancy, for loving and pushing me to get this far. My colleague, Liz, for being a great friend and listener throughout the drafting of this thesis. Dr. Haagen Klaus, for helping me throughout every process of this paper and mentoring me through this process. I’d also like to thank my committee members, Dr. Daniel Temple and Dr. Cortney Hughes Rinker. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page Dedication .......................................................................................................................... -

Chapter Summary

0033-wh10a-CIB-02 11/13/2003 12:07 PM Page 33 Name Date CHAPTER CHAPTERS IN BRIEF The Americas: A Separate World, 9 40,000 B.C.–A.D. 700 Summary CHAPTER OVERVIEW Long ago, huge ice sheets cover the land. The level of the oceans goes down, and a once-underwater bridge of land connects Asia and the Americas. Asian hunters cross this bridge and become the first Americans. They spread down the two continents. They develop more complex societies and new civilizations. The earliest of these new cultures are found in central Mexico and in the high Andes Mountains. 1 The Earliest Americans with thick, long hair to protect it from the bitter KEY IDEA The first Americans were separated from cold of the Ice Age. It was so large that one animal other parts of the world. Nevertheless, they developed in alone gave enough meat, hide, and bones to feed, similar ways. clothe, and house many people. orth and South America form a single stretch Over time, all the mammoths died, and the peo- Nof land that reaches from the freezing cold ple were forced to look for other food. They began of the Arctic Circle in the north to the icy waters to hunt smaller animals such as rabbits and deer around Antarctica in the south. Two oceans on and to fish. They also began to gather plants and either side of these land masses separate them fruits to eat. Because they no longer had to roam from Africa, Asia, and Europe. over large areas to search for the mastodon, they That was not always the case, though.