Words for Canoes: Continuity and Change in Oceanic Sailing Craft

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trimarans and Outriggers

TRIMARANS AND OUTRIGGERS Arthur Fiver's 12' fibreglass Trimaran with solid plastic foam floats CONTENTS 1. Catamarans and Trimarans 5. A Hull Design 2. The ROCKET Trimaran. 6. Micronesian Canoes. 3. JEHU, 1957 7. A Polynesian Canoe. 4. Trimaran design. 8. Letters. PRICE 75 cents PRICE 5 / - Amateur Yacht Research Society BCM AYRS London WCIN 3XX UK www.ayrs.org office(S)ayrs .org Contact details 2012 The Amateur Yacht Research Society {Founded June, 1955) PRESIDENTS BRITISH : AMERICAN : Lord Brabazon of Tara, Walter Bloemhard. G.B.E., M.C, P.C. VICE-PRESIDENTS BRITISH : AMERICAN : Dr. C. N. Davies, D.sc. John L. Kerby. Austin Farrar, M.I.N.A. E. J. Manners. COMMITTEE BRITISH : Owen Dumpleton, Mrs. Ruth Evans, Ken Pearce, Roland Proul. SECRETARY-TREASURERS BRITISH : AMERICAN : Tom Herbert, Robert Harris, 25, Oakwood Gardens, 9, Floyd Place, Seven Kings, Great Neck, Essex. L.I., N.Y. NEW ZEALAND : Charles Satterthwaite, M.O.W., Hydro-Design, Museum Street, Wellington. EDITORS BRITISH : AMERICAN : John Morwood, Walter Bloemhard "Woodacres," 8, Hick's Lane, Hythe, Kent. Great Neck, L.I. PUBLISHER John Morwood, "Woodacres," Hythc, Kent. 3 > EDITORIAL December, 1957. This publication is called TRIMARANS as a tribute to Victor Tchetchet, the Commodore of the International MultihuU Boat Racing Association who really was the person to introduce this kind of craft to Western peoples. The subtitle OUTRIGGERS is to include the ddlightful little Micronesian canoe made by A. E. Bierberg in Denmark and a modern Polynesian canoe from Rarotonga which is included so that the type will not be forgotten. The main article is written by Walter Bloemhard, the President of the American A.Y.R.S. -

Chartmaking in England and Its Context, 1500–1660

58 • Chartmaking in England and Its Context, 1500 –1660 Sarah Tyacke Introduction was necessary to challenge the Dutch carrying trade. In this transitional period, charts were an additional tool for The introduction of chartmaking was part of the profes- the navigator, who continued to use his own experience, sionalization of English navigation in this period, but the written notes, rutters, and human pilots when he could making of charts did not emerge inevitably. Mariners dis- acquire them, sometimes by force. Where the navigators trusted them, and their reluctance to use charts at all, of could not obtain up-to-date or even basic chart informa- any sort, continued until at least the 1580s. Before the tion from foreign sources, they had to make charts them- 1530s, chartmaking in any sense does not seem to have selves. Consequently, by the 1590s, a number of ship- been practiced by the English, or indeed the Scots, Irish, masters and other practitioners had begun to make and or Welsh.1 At that time, however, coastal views and plans sell hand-drawn charts in London. in connection with the defense of the country began to be In this chapter the focus is on charts as artifacts and made and, at the same time, measured land surveys were not on navigational methods and instruments.4 We are introduced into England by the Italians and others.2 This lack of domestic production does not mean that charts I acknowledge the assistance of Catherine Delano-Smith, Francis Her- and other navigational aids were unknown, but that they bert, Tony Campbell, Andrew Cook, and Peter Barber, who have kindly commented on the text and provided references and corrections. -

A History of the Pacific Islands

A HISTORY OF THE PACIFIC ISLANDS I. C. Campbell A HISTORY OF THE PACIFIC ISLANDS Thi s One l N8FG-03S-LXLD A History of the Pacific Islands I. C. CAMPBELL University of California Press Berkeley • Los Angeles Copyrighted material © 1989 I. C. Campbell Published in 1989 in the United States of America by the University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles All rights reserved. Apart from any fair use for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review, no part whatsoever may by reproduced by any process without the express written permission of the author and the University of California Press. Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Campbell, LC. (Ian C), 1947- A history of the Pacific Islands / LC. Campbell, p. cm. "First published in 1989 by the University of Canterbury Press, Christchurch, New Zealand" — T.p. verso. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-520-06900-5 (alk. paper). — ISBN 0-520-06901-3 (pbk. alk. paper) 1. Oceania — History. I. Title DU28.3.C35 1990 990 — dc20 89-5235 CIP Typographic design: The Caxton Press, Christchurch, New Zealand Cover design: Max Hailstone Cartographer: Tony Shatford Printed by: Kyodo-Shing Loong Singapore C opy righted m ateri al 1 CONTENTS List of Maps 6 List of Tables 6 A Note on Orthography and Pronunciation 7 Preface. 1 Chapter One: The Original Inhabitants 13 Chapter Two: Austronesian Colonization 28 Chapter Three: Polynesia: the Age of European Discovery 40 Chapter Four: Polynesia: Trade and Social Change 57 Chapter Five: Polynesia: Missionaries and Kingdoms -

Seacare Authority Exemption

EXEMPTION 1—SCHEDULE 1 Official IMO Year of Ship Name Length Type Number Number Completion 1 GIANT LEAP 861091 13.30 2013 Yacht 1209 856291 35.11 1996 Barge 2 DREAM 860926 11.97 2007 Catamaran 2 ITCHY FEET 862427 12.58 2019 Catamaran 2 LITTLE MISSES 862893 11.55 2000 857725 30.75 1988 Passenger vessel 2001 852712 8702783 30.45 1986 Ferry 2ABREAST 859329 10.00 1990 Catamaran Pleasure Yacht 2GETHER II 859399 13.10 2008 Catamaran Pleasure Yacht 2-KAN 853537 16.10 1989 Launch 2ND HOME 856480 10.90 1996 Launch 2XS 859949 14.25 2002 Catamaran 34 SOUTH 857212 24.33 2002 Fishing 35 TONNER 861075 9714135 32.50 2014 Barge 38 SOUTH 861432 11.55 1999 Catamaran 55 NORD 860974 14.24 1990 Pleasure craft 79 199188 9.54 1935 Yacht 82 YACHT 860131 26.00 2004 Motor Yacht 83 862656 52.50 1999 Work Boat 84 862655 52.50 2000 Work Boat A BIT OF ATTITUDE 859982 16.20 2010 Yacht A COCONUT 862582 13.10 1988 Yacht A L ROBB 859526 23.95 2010 Ferry A MORNING SONG 862292 13.09 2003 Pleasure craft A P RECOVERY 857439 51.50 1977 Crane/derrick barge A QUOLL 856542 11.00 1998 Yacht A ROOM WITH A VIEW 855032 16.02 1994 Pleasure A SOJOURN 861968 15.32 2008 Pleasure craft A VOS SANTE 858856 13.00 2003 Catamaran Pleasure Yacht A Y BALAMARA 343939 9.91 1969 Yacht A.L.S.T. JAMAEKA PEARL 854831 15.24 1972 Yacht A.M.S. 1808 862294 54.86 2018 Barge A.M.S. -

A Comparative Evaluation of a Hydrofoil-Assisted Trimaran

COMPARATIVE EVALUATION OF A A HYDROFOIL-ASSISTED TRIMARAN Thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF SCIENCE IN ENGINEERING By Ryno Moolman Supervisor Prof. T.M. Harms Department of Mechanical Engineering University of Stellenbosch Co-supervisor Dr. G. Migeotte CAE Marine December 2005 Declaration I, the undersigned, declare that the work contained in this thesis is my own original work and has not previously, in its entirety or in part, been submitted at any University for a degree. Signature of Candidate Date i Abstract This work is concerned with the design and hydrodynamic aspects of a hydrofoil-assisted trimaran. A design and configuration of a trimaran is evaluated and the performance of a hydrofoil-assisted trimaran is effectively compared to the performance of a hydrofoil-assisted catamaran with similar overall displacement and same speed. The performance of the trimaran with different outrigger clearances are also evaluated and compared. The hydrodynamic aspects focuses mainly on the performance and to a lesser extend on the sea-keeping and stability of a hydrofoil-assisted trimaran. The results were determined by means of experimental testing, theoretical analysis and numerical analysis. The project was initiated as a result of the success of the hydrofoil-assisted catamarans and due to the fact that there does not exist a hydrofoil-assisted trimaran (to the author’s knowledge) where the main focus of the foils is to significantly reduce the resistance. A brief history, recent developments and associated advantages regarding trimarans are discussed. A complete theoretical model is presented to evaluate the lift and drag of the hydrofoils, as well as, the resistance of the trimaran. -

By Dylan Rose

TheULTIMATE ATOLL A Saltwater Utopia for the Adventuresome Angler by Dylan Rose he moment I set foot on Christmas Island my life was changed forever. My first visit was a metaphorical abstraction of the island’s vibe, culture, warmth and relaxed pace. As I stepped off of the big Fiji Airways 737 onto the tarmac I noticed from Tbehind the airport fence a small gathering of villagers quietly watching us deplane. Some of the island’s sun-kissed, bronzed-faced children were standing behind the chain link fence, smiling and waving excitedly. I Dylan Rose tracks a GT that turned to look behind me expecting to see a familiar party waving back, was spotted from the boat. but I soon realized their brilliant white smiles were actually for me and my Photo: Brian Gies intrepid gang of arriving fly anglers. PAGE 1 The ULTIMATE ATOLL Of all the places I’ve traveled, the feeling of being truly welcome in a the Pacific Ocean. Captain Cook landed on the island on Christmas Eve in foreign land is the strongest at Christmas Island. It’s the attribute about the 1777 and I can only imagine what a great holiday it might have been if he had place that connects me most to it. It’s baffling to me how a locale so far packed an 8-weight and a few Gotchas. away and different from anything I know can somehow still feel so much Blasted by high altitude, British H-bomb testing in the late 1950s and like home. From the giddy bouncing children swimming in the boat harbor again by the United States in the 1960s, Christmas Island and its magnificent to the villagers tending their chores; to the guides and their families, the lodge population of seabirds got a front row view of the inception of the atomic age. -

Forecast 1954

. UTRIGGER CAN0E CLUB JUNE FORECAST 1954 ‘'It’s Kamehameha Day—Come Buy a Lei" (This is a scene we hope will never disappear in Hawaii.) flairaii Visitors Bureau Pic SEE PAGE 5 — ENTERTAINMENT CALENDAR Fora longer smoother ride... Enjoy summer’s coolest drink. G I V I AND Quinac The quickest way to cool contentment in a glass . Gin-and-Quinac. Just put IV2 ounces of gin in a tall glass. Plenty of ice. Thin slice of P. S. Hnjoy Q u in a c as a delicious beverage. Serve lemon or lime. Fill with it by itself in a glass with Quinac . and you have an lots of ice and a slice of easy to take, deliciously dry, lemon or lime. delightfully different drink. CANADA DRY BOTTLING CO. (HAWAII) LTD. [2] OUTRIGGER CANOE CLUB V o l. 13 N o. « Founded 190S WAIKIKI BEACH HONOLULU, HAWAII OFFICERS SAMUEL M. FULLER...............................................President H. VINCENT DANFORD............................ Vice-President MARTIN ANDERSON............................................Secretary H. BRYAN RENWICK..........................................Treasurer OIECASI DIRECTORS Issued by the Martin Andersen Leslie A. Hicks LeRoy C. Bush Henry P. Judd BOARD OF DIRECTORS H. Vincent Danford Duke P. Kahanamoku William Ewing H. Bryan Renwlck E. W. STENBERG.....................Editor Samuel M. Fuller Fred Steere Bus. Phone S-7911 Res. Phone 99-7664 W illard D. Godbold Herbert M. Taylor W. FRED KANE, Advertising.............Phone 9*4806 W. FREDERICK KANE.......................... General Manager CHARLES HEEf Adm in. Ass't COMMITTEES FINANCE—Samuel Fuller, Chairman. Members: Les CASTLE SW IM -A. E. Minvlelle, Jr., Chairman. lie Hicks, Wilford Godbold, H. V. Danford, Her bert M. -

A Mortal Antipathy

A MORTAL ANTIPATHY Oliver Wendell Holmes A MORTAL ANTIPATHY Table of Contents A MORTAL ANTIPATHY......................................................................................................................................1 Oliver Wendell Holmes.................................................................................................................................1 PREFACE......................................................................................................................................................1 FIRST OPENING OF THE NEW PORTFOLIO.......................................................................................................2 INTRODUCTION.........................................................................................................................................2 I. GETTING READY..................................................................................................................................14 II. THE BOAT−RACE................................................................................................................................19 III. THE WHITE CANOE...........................................................................................................................22 IV.................................................................................................................................................................24 V. THE ENIGMA STUDIED......................................................................................................................29 -

Sail Power and Performance

the area of Ihe so-called "fore-triangle"), the overlapping part of headsail does not contribute to the driving force. This im plies that it does pay to have o large genoa only if the area of the fore-triangle (or 85 per cent of this area) is taken as the rated sail area. In other words, when compared on the basis of driving force produced per given area (to be paid for), theoverlapping genoas carried by racing yachts are not cost-effective although they are rating- effective in term of measurement rules (Ref. 1). In this respect, the rating rules have a more profound effect on the plan- form of sails thon aerodynamic require ments, or the wind in all its moods. As explicitly demonstrated in Fig. 2, no rig is superior over the whole range of heading angles. There are, however, con sistently poor performers such ns the La teen No. 3 rig, regardless of the course sailed relative to thewind. When reaching, this version of Lateen rig is inferior to the Lateen No. 1 by as rnuch as almost 50 per cent. To the surprise of many readers, perhaps, there are more efficient rigs than the Berntudan such as, for example. La teen No. 1 or Guuter, and this includes windward courses, where the Bermudon rig is widely believed to be outstanding. With the above data now available, it's possible to answer the practical question: how fast will a given hull sail on different headings when driven by eoch of these rigs? Results of a preliminary speed predic tion programme are given in Fig. -

Navigation Map Our Future Animals Created with Genetically Engineered Homing Devices ——— Finding Our Way ———

Published by Adams, Schwartz & Evans, P.A. Asymptote ® 2001, Vol. 9 A Journal of Intellectual Property Law Issues No. 1 Advances in Navigation Map Our Future Animals Created with Genetically Engineered Homing Devices ——— Finding Our Way ——— efore Magellan circled the globe, symptote Review is now in its Before coming ashore eighteen-hundred before Alexander invaded Africa, ninth year of publication, and miles away on a small Caribbean island, even before our species painted the during that time its subscription Callahan used ingenuity, bravery and walls of caves, humankind and other animals had to find their way to A list has grown from a few incredible skill as a navigator to success- B hundred to over one thousand, five fully plot his course to safety. hunting grounds and home again. Fortunately, knowing how essential navigation is to her hundred. Of all the issues we have We recently asked Steve and his many children, Mother Nature imbued most published, the first issue in 1998 gener- colleague, Kathy Massimini, if they would complex animals with numerous navigational ated by far the most reader response and author an issue of Asymptote Review tools, such as the built-in compasses of interest. In it, we explored the validity of devoted to the history of navigation, and magnetite that she placed into the skulls of the old saying “necessity is the mother of they graciously agreed. This issue will be many migrators. Real-life shanghaied Lassies invention” with the story of Steve of great interest not only to the pilot, hiker have traveled hundreds of miles to find their Callahan, who in 1982 survived for 76 or sailor, but to anyone who is curious dog dishes again. -

Creating Equitable South- North Partnerships: Nurturing the Vā and Voyaging the Audacious Ocean Together

CREATING EQUITABLE SOUTH- NORTH PARTNERSHIPS: NURTURING THE VĀ AND VOYAGING THE AUDACIOUS OCEAN TOGETHER A Case Study in the Oceanic Pacific ‘Ofa-Ki-Levuka Louise Guttenbeil-Likiliki 35 women leaders from the Global South OCTOBER 2020 courageously share their perspectives of engagement with Global North organisations 1990-2020 2 we sweat and cry salt water, so we know that the ocean is really in our blood Teaiwa (2008) 3 CREATING EQUITABLE SOUTH-NORTH PARTNERSHIPS: NURTURING THE VĀ AND VOYAGING THE AUDACIOUS OCEAN TOGETHER This report was written by ‘Ofa-Ki-Levuka Guttenbeil-Likiliki. Artwork concept and illustrations by IVI Designs. Design and layout by Gregory Ravoi. Copyright © IWDA 2020. ‘Ofa-Ki-Levuka Guttenbeil-Likiliki, the artists and IWDA give permission for excerpts from the report to be used and reproduced provided that the author, artists and source are properly and clearly acknowledged. Suggested citation: Guttenbeil-Likiliki, ‘Ofa-Ki-Levuka (2020), Creating Equitable South-North Partnerships: Nurturing the Vā and Voyaging the Audacious Ocean Together, Melbourne: IWDA. ISBN: 978-0-6450082-0-3 4 A CASE STUDY IN THE OCEANIC PACIFIC TABLE OF CONTENTS Greeting from the author 7 Executive Summary 10 Introduction 18 Key Findings 24 Recommendations 54 Conclusion 58 References 60 Annexes: 1. Guidance Literature Review 64 2. Talanoa Research Methodology: Decolonizing Knowledge 72 3. Focus on Three Organisations and One Regional Network 76 4. Participant Information and Consent Form 86 5. Research Guiding Questions 89 Each section of this report commences with a quote from conversations with Oceanic researchers, academics, feminists, activists and research participants. Each quote represents a wave of Oceania in its diversity and audacity. -

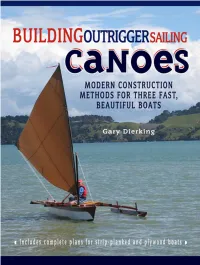

Building Outrigger Sailing Canoes

bUILDINGOUTRIGGERSAILING CANOES INTERNATIONAL MARINE / McGRAW-HILL Camden, Maine ✦ New York ✦ Chicago ✦ San Francisco ✦ Lisbon ✦ London ✦ Madrid Mexico City ✦ Milan ✦ New Delhi ✦ San Juan ✦ Seoul ✦ Singapore ✦ Sydney ✦ Toronto BUILDINGOUTRIGGERSAILING CANOES Modern Construction Methods for Three Fast, Beautiful Boats Gary Dierking Copyright © 2008 by International Marine All rights reserved. Manufactured in the United States of America. Except as permitted under the United States Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher. 0-07-159456-6 The material in this eBook also appears in the print version of this title: 0-07-148791-3. All trademarks are trademarks of their respective owners. Rather than put a trademark symbol after every occurrence of a trademarked name, we use names in an editorial fashion only, and to the benefit of the trademark owner, with no intention of infringement of the trademark. Where such designations appear in this book, they have been printed with initial caps. McGraw-Hill eBooks are available at special quantity discounts to use as premiums and sales promotions, or for use in corporate training programs. For more information, please contact George Hoare, Special Sales, at [email protected] or (212) 904-4069. TERMS OF USE This is a copyrighted work and The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. (“McGraw-Hill”) and its licensors reserve all rights in and to the work. Use of this work is subject to these terms. Except as permitted under the Copyright Act of 1976 and the right to store and retrieve one copy of the work, you may not decompile, disassemble, reverse engineer, reproduce, modify, create derivative works based upon, transmit, distribute, disseminate, sell, publish or sublicense the work or any part of it without McGraw-Hill’s prior consent.