Chartmaking in England and Its Context, 1500–1660

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PEAES Guide: the Historical Society of Pennsylvania

PEAES Guide: The Historical Society of Pennsylvania http://www.librarycompany.org/Economics/PEAESguide/hsp.htm Keyword Search Entire Guide View Resources by Institution Search Guide Institutions Surveyed - Select One The Historical Society of Pennsylvania 1300 Locust Street Philadelphia, PA 19107 215-732-6200 http://www.hsp.org Overview: The entries in this survey highlight some of the most important collections, as well as some of the smaller gems, that researchers will find valuable in their work on the early American economy. Together, they are a representative sampling of the range of manuscript collections at HSP, but scholars are urged to pursue fruitful lines of inquiry to locate and use the scores of additional materials in each area that is surveyed here. There are numerous helpful unprinted guides at HSP that index or describe large collections. Some of these are listed below, especially when they point in numerous directions for research. In addition, the HSP has a printed Guide to the Manuscript Collections of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania (HSP: Philadelphia, 1991), which includes an index of proper names; it is not especially helpful for searching specific topics, item names, of subject areas. In addition, entries in the Guide are frequently too brief to explain the richness of many collections. Finally, although the on-line guide to the manuscript collections is generally a reproduction of the Guide, it is at present being updated, corrected, and expanded. This survey does not contain a separate section on land acquisition, surveying, usage, conveyance, or disputes, but there is much information about these subjects in the individual collections reviewed below. -

A History of the British Library Slavonic and East European Collections: 1952-2004

A History of the British Library Slavonic and East European Collections: 1952-2004 Milan Grba Preface The purpose of this article is to provide an introduction to the British Library Slavonic and East European Department oral history interviews project. The project was carried out over two years, and nineteen former Slavonic and East European department staff took part in it in 2011 and 2012. The material from the oral history project and description in more detail can be accessed via the British Library Sound and Moving Image Catalogue (http://cadensa.bl.uk/cgi-bin/webcat) as the entry ‘the British Library Slavonic and East European Oral History Interviews’. This article is limited only to information that has not been discussed in interviews or published in previous research on the British Library collections.1 It draws on two main sources of information. The unpublished primary sources which were consulted are held in the British Library Archives in the DH 2 series and the published sources were derived from P. R. Harris, A History of the British Museum Library, 1753-1973 (London, 1998).2 The British Library staff office notices were also consulted for the period 1973 to 2000, but this period is examined to a lesser extent. This is partly due to the information already provided in the interviews and partly to the time limits imposed upon the research for this article. Much more attention is needed for the post-1973 period, and without a full grasp and understanding of the archive sources it would be not possible properly to assess the available information held in the British Library 1 Such as P. -

Introduction Day To

Cycling over the Veluwe - 6 dagen DUTCH BIKETOURS - EMAIL: [email protected] - TELEPHONE +31 (0)24 3244712 - WWW.DUTCH-BIKETOURS.COM Cycling over the Veluwe 6 days, € 410 Introduction This tour has been designed for cyclists who want to truly live life to the full. During the day, you cycle through beautiful natural scenery and in the evenings you stay at Westcord Hotel de Veluwe in the village of Garderen. For no fewer than six days - what a treat! Westcord Hotel de Veluwe is known for its comfort, culinary qualities and hospitality. Your cycling holiday has never been so comfortable! The routes surprise you with a wealth of natural beauty and interesting sights. You can visit the Hoge Veluwe National Park with the Kröller-Muller museum, the Royal Palace Het Loo or the Hanseatic city of Harderwijk. During your stay, you can choose from 4 different bicycle routes. Each day you will have 3 distances to choose from. Day to Day Day 1 Arrival at Garderen Your hotel is situated in a unique part of the Netherlands: the centre of The Veluwe. Today, you have plenty of time to take in the beautiful surroundings. The welcoming village of Garderen is certainly worth a visit. Day 2 Route Northern Veluwe 56 km Vast forests, purple-colored heather fields, picturesque towns and charming cities: with the Noord Veluwe route you can see it all. You cycle over the Ermelose Heide, a heathland of no less than 343 hectares. You may encounter a shepherd with his sheepfold on the way. The largest sheep herd in Europe is located on the Ermelose heath. -

Expressions of Sovereignty: Law and Authority in the Making of the Overseas British Empire, 1576-1640

EXPRESSIONS OF SOVEREIGNTY EXPRESSIONS OF SOVEREIGNTY: LAW AND AUTHORITY IN THE MAKING OF THE OVERSEAS BRITISH EMPIRE, 1576-1640 By KENNETH RICHARD MACMILLAN, M.A. A Thesis . Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy McMaster University ©Copyright by Kenneth Richard MacMillan, December 2001 DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (2001) McMaster University (History) Hamilton, Ontario TITLE: Expressions of Sovereignty: Law and Authority in the Making of the Overseas British Empire, 1576-1640 AUTHOR: Kenneth Richard MacMillan, B.A. (Hons) (Nipissing University) M.A. (Queen's University) SUPERVISOR: Professor J.D. Alsop NUMBER OF PAGES: xi, 332 11 ABSTRACT .~. ~ This thesis contributes to the body of literature that investigates the making of the British empire, circa 1576-1640. It argues that the crown was fundamentally involved in the establishment of sovereignty in overseas territories because of the contemporary concepts of empire, sovereignty, the royal prerogative, and intemationallaw. According to these precepts, Christian European rulers had absolute jurisdiction within their own territorial boundaries (internal sovereignty), and had certain obligations when it carne to their relations with other sovereign states (external sovereignty). The crown undertook these responsibilities through various "expressions of sovereignty". It employed writers who were knowledgeable in international law and European overseas activities, and used these interpretations to issue letters patent that demonstrated both continued royal authority over these territories and a desire to employ legal codes that would likely be approved by the international community. The crown also insisted on the erection of fortifications and approved of the publication of semiotically charged maps, each of which served the function of showing that the English had possession and effective control over the lands claimed in North and South America, the North Atlantic, and the East and West Indies. -

Investment in the East India Company

The University of Manchester Research The Global Interests of London's Commercial Community, 1599-1625: investment in the East India Company DOI: 10.1111/ehr.12665 Document Version Accepted author manuscript Link to publication record in Manchester Research Explorer Citation for published version (APA): Smith, E. (2018). The Global Interests of London's Commercial Community, 1599-1625: investment in the East India Company. The Economic History Review, 71(4), 1118-1146. https://doi.org/10.1111/ehr.12665 Published in: The Economic History Review Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on Manchester Research Explorer is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Proof version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Explorer are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Takedown policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please refer to the University of Manchester’s Takedown Procedures [http://man.ac.uk/04Y6Bo] or contact [email protected] providing relevant details, so we can investigate your claim. Download date:05. Oct. 2021 The global interests of London’s commercial community, 1599-1625: investment in the East India Company The English East India Company (EIC) has long been identified as an organisation that foreshadowed developments in finance, investment and overseas expansion that would come to fruition over the course of the following two centuries. -

Cc Arbitrary Rule" and the Eighteenth-Century Discourse Ojguinea

cc Arbitrary rule" and the Eighteenth-Century Discourse ojGuinea MALVERN VAN WYK SMITH INTRODUCING THE English edition of Anders Sparrman's Voyage to the Cape of Good Hope in 1785, the anonymous translator remarks: "Now every authentic and well-written book of voyages and travels is, in fact, a treatise of experimental philosophy" ( 1.27). By the late eighteenth century Africa had become a par• ticularly popular focus and subject for such speculation. The Criti• cal Review wrote in October 1792 : "To explore the internal parts of Africa seems now to be the great subject of the philosopher, the botanist, and the politician" (qtd. in James 19). But the phenom• enon was hardly new, and in this paper I shall attempt to show how a particular late seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century discourse of Africa shaped certain later Enlightenment preoccupa• tions which preceded the abolition of slavery. My argument will be that the obsessive concern in African travelogues of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries with the apparent "cruelty" and "despot• ism" of African forms of rule was not the expression of purblind ethnocentricity that it is now often taken to be, but was rather the imprint of an anxious contemporary European polemic surround• ing the European transition from absolutist to constitutional monarchies. Travel writing lends itself readily to the speculative survey. Travelling into and through the unknown is essentially a herme- neutic process, a reading of the unfamiliar which thus becomes a constitutive process, in which the "eye/1" of traveller/narrator constructs, as much as discovers, the object of investigation. -

Inter Departmental Archives Committee Action Plan On

Inter Departmental Archives Committee Government Policy on Archives: Action Plan Foreword from the Keeper of Public Records In my capacity as Chair of the United Kingdom Inter-Departmental Archives Committee (IDAC), which I chair on the behalf of the Lord Chancellor, I am pleased to present the Action Plan to accompany the Government Policy on Archives (Cm 4516, December 1999). The Plan, which has been the subject of extensive consultation, is intended to provide a general framework for the activities of the leading archive bodies, both inside and outside Government, towards achieving the high-level outcomes set out in the main policy document, over the next three years or so. As well as the relevant Government Departments, Resource (the Council for Museums, Archives and Libraries), the National Council on Archives (NCA), and the Association of Chief Archivists in Local Government (ACALG) will all play a major role in the Plan's implementation. IDAC's secretariat will regularly monitor and publish progress against the agreed action points set out in the Plan. Shortly after the Plan was approved at official level, Baroness Blackstone, Minister of State for the Arts, announced on 12 July that the functions of the Public Record Office (PRO) and the Historical Manuscripts Commission (HMC) are to be brought together in a single new organisation, called the National Archives, which will come under the Lord Chancellor. This will come into effect on 1 April 2003. In the Action Plan the PRO is designated the lead body for objectives 3 (records and archives management in the public sector) and 5 (the archiving of electronic data), while HMC is the lead body for objective 4 (promoting standards in private archives). -

3B – a Guide to Pictograms

3b – A Guide to Pictograms A pictogram involves the use of a symbol in place of a word or statistic. Why would we use a pictogram? Pictograms can be very useful when trying to interpret data. The use of pictures allows the reader to easily see the frequency of a geographical phenomenon without having to always read labels and annotations. They are best used when the aesthetic qualities of the data presentation are more important than the ability to read the data accurately. Pictogram bar charts A normal bar chart can be made using a set of pictures to make up the required bar height. These pictures should be related to the data in question and in some cases it may not be necessary to provide a key or explanation as the pictures themselves will demonstrate the nature of the data inherently. A key may be needed if large numbers are being displayed – this may also mean that ‘half’ sized symbols may need to be used too. This project was funded by the Nuffield Foundation, but the views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Foundation. Proportional shapes and symbols Scaling the size of the picture to represent the amount or frequency of something within a data set can be an effective way of visually representing data. The symbol should be representative of the data in question, or if the data does not lend itself to a particular symbol, a simple shape like a circle or square can be equally effective. Proportional symbols can work well with GIS, where the symbols can be placed on different sites on the map to show a geospatial connection to the data. -

Robert Dudley, 1St Earl of Leicester

Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester, KG (24 June mours that he had arranged for his wife’s death continued 1532 or 1533[note 1] – 4 September 1588) was an English throughout his life, despite the coroner’s jury's verdict of nobleman and the favourite and close friend of Elizabeth accident. For 18 years he did not remarry for Queen Eliz- I from her first year on the throne until his death. The abeth’s sake and when he finally did, his new wife, Lettice Queen giving him reason to hope, he was a suitor for her Knollys, was permanently banished from court. This and hand for many years. the death of his only legitimate son and heir were heavy blows.[2] Shortly after the child’s death in 1584, a viru- Dudley’s youth was overshadowed by the downfall of his family in 1553 after his father, the Duke of Northumber- lent libel known as Leicester’s Commonwealth was circu- land, had unsuccessfully tried to establish Lady Jane Grey lating in England. It laid the foundation of a literary and historiographical tradition that often depicted the Earl as on the English throne. Robert Dudley was condemned to [3] death but was released in 1554 and took part in the Battle the Machiavellian “master courtier” and as a deplorable of St. Quentin under Philip II of Spain, which led to his figure around Elizabeth I. More recent research has led full rehabilitation. On Elizabeth I’s accession in Novem- to a reassessment of his place in Elizabethan government ber 1558, Dudley was appointed Master of the Horse. -

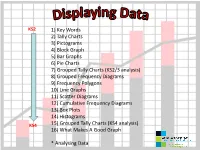

1) Key Words 2) Tally Charts 3) Pictograms 4) Block Graph 5) Bar

KS2 1) Key Words 2) Tally Charts 3) Pictograms 4) Block Graph 5) Bar Graphs 6) Pie Charts 7) Grouped Tally Charts (KS2/3 analysis) 8) Grouped Frequency Diagrams 9) Frequency Polygons 10) Line Graphs 11) Scatter Diagrams 12) Cumulative Frequency Diagrams 13) Box Plots 14) Histograms KS4 15) Grouped Tally Charts (KS4 analysis) 16) What Makes A Good Graph * Analysing Data Key words Axes Linear Continuous Median Correlation Origin Plot Data Discrete Scale Frequency x -axis Grouped y -axis Interquartile Title Labels Tally Types of data Discrete data can only take specific values, e.g. siblings, key stage 3 levels, numbers of objects Continuous data can take any value, e.g. height, weight, age, time, etc. Tally Chart A tally chart is used to organise data from a list into a table. The data shows the number of children in each of 30 families. 2, 1, 5, 0, 2, 1, 3, 0, 2, 3, 2, 4, 3, 1, 2, 3, 2, 1, 4, 0, 1, 3, 1, 2, 2, 6, 3, 2, 2, 3 Number of children in a Tally Frequency family 0 1 2 3 4 or more Year 3/4/5/6:- represent data using: lists, tally charts, tables and diagrams Tally Chart This data can now be represented in a Pictogram or a Bar Graph The data shows the number of children in each family. 30 families were studied. Add up the tally Number of children in a Tally Frequency family 0 III 3 1 IIII I 6 2 IIII IIII 10 3 IIII II 7 4 or more IIII 4 Total 30 Check the total is 30 IIII = 5 Year 3/4/5/6:- represent data using: lists, tally charts, tables and diagrams Pictogram This data could be represented by a Pictogram: Number of Tally Frequency -

2021 Garmin & Navionics Cartography Catalog

2021 CARTOGRAPHY CATALOG CONTENTS BlueChart® Coastal Charts �� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 04 LakeVü Inland Maps �� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 06 Canada LakeVü G3 �� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 08 ActiveCaptain® App �� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 09 New Chart Guarantee� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 10 How to Read Your Product ID Code �� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 10 Inland Maps ��������������������������������������������������� 12 Coastal Charts ������������������������������������������������� 16 United States� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 18 Canada ���������������������������������������������������� 24 Caribbean �������������������������������������������������� 26 South America� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 27 Europe����������������������������������������������������� 28 Africa ����������������������������������������������������� 39 Asia ������������������������������������������������������ 40 Australia/New Zealand �� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 42 Pacific Islands �� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � -

International Rate Centers for Virtual Numbers

8x8 International Virtual Numbers Country City Country Code City Code Country City Country Code City Code Argentina Bahia Blanca 54 291 Australia Brisbane North East 61 736 Argentina Buenos Aires 54 11 Australia Brisbane North/North West 61 735 Argentina Cordoba 54 351 Australia Brisbane South East 61 730 Argentina Glew 54 2224 Australia Brisbane West/South West 61 737 Argentina Jose C Paz 54 2320 Australia Canberra 61 261 Argentina La Plata 54 221 Australia Clayton 61 385 Argentina Mar Del Plata 54 223 Australia Cleveland 61 730 Argentina Mendoza 54 261 Australia Craigieburn 61 383 Argentina Moreno 54 237 Australia Croydon 61 382 Argentina Neuquen 54 299 Australia Dandenong 61 387 Argentina Parana 54 343 Australia Dural 61 284 Argentina Pilar 54 2322 Australia Eltham 61 384 Argentina Rosario 54 341 Australia Engadine 61 285 Argentina San Juan 54 264 Australia Fremantle 61 862 Argentina San Luis 54 2652 Australia Herne Hill 61 861 Argentina Santa Fe 54 342 Australia Ipswich 61 730 Argentina Tucuman 54 381 Australia Kalamunda 61 861 Australia Adelaide City Center 61 871 Australia Kalkallo 61 381 Australia Adelaide East 61 871 Australia Liverpool 61 281 Australia Adelaide North East 61 871 Australia Mclaren Vale 61 872 Australia Adelaide North West 61 871 Australia Melbourne City And South 61 386 Australia Adelaide South 61 871 Australia Melbourne East 61 388 Australia Adelaide West 61 871 Australia Melbourne North East 61 384 Australia Armadale 61 861 Australia Melbourne South East 61 385 Australia Avalon Beach 61 284 Australia Melbourne