Trimarans and Outriggers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Great Trimaran-Catamaran Debate

On the Great Trimaran-Catamaran Debate Lawrence J. Doctors, Member, School of MechanicnJ and Manufacturing Engineering, The University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW 2052, Australia Abdmct In the cumwtt work, a aydewaatic investigation into a variety of monohulls and mul- tihulls is carried out with an emphasis on finding optimal forms. Vessels with up to six identical subhulls are taken into consideration and a large range of lengths is studied. hT- thermore, sidehuli trimaran configurations are included in the investigation. There are two main purposes to this investigation. Firstly, one is interested in mini- mizing the wave resistance, becawe this is closely related to the wave generation and is of critical importance to the operation of river ferries. Secondly, it is also important to min- imize the total resistance, in order to reduce fuei costs and to permit long-range trips for ocean-going vessels. The theoretical predictions show that increasing the length beyond that normally accepted is beneficial in reducing both the wave Resistance and often the total resistance. I. the goal is to minimize wave resistance and if the length is constrained, the calculations also demon- strate that trimarans are superior to catamarans, which are in turn superior to monohulls. On the other hand, if the goal is to minimize the total resistance, then all the muh!ihulis (~m catamarans to hezamarans) are inferior to monohulls, except possibly at low speeds which are not of interest in thw study. Similarly, sidehull trimarans are shown to be inferior to catamarans except perhaps if rather great lengths are permitted. -

5 Must Read Sailing Books for Catamaran Enthusiasts

5 Must Read Sailing Books for Catamaran Enthusiasts This list briefly discusses 5 books that yacht owners or enthusiasts should read. What makes each book unique? Why should they read the book? What will they learn or take away from it? This is - at least what we consider - the best 5 books ever written in English on the subject of cruising catamarans. There are a few German and French publications but they are nearly impossible to get , most are out of print and unless you can read German or French - are of no value. So here is the top 5 list of the "Must Read books for Catamaran Enthusiasts" 1.) CATAMARANS - THE COMPLETE GUIDE FOR CRUISING SAILORS, by Gregor Tarjan. First published in 2006 and reprinted in 2008 by Mc Graw Hill Companies, New York. ISBN 9780071498852. Hardcover, 305 pages full color, large format, illustrated and lavish photography by Gilles Martin Raget. Of course we have to mention this book first. Not only is it written by our own Gregor Tarjan, founder and owner of Aeroyacht Ltd., but it is hailed as "the industry reference" by many experts. It has sold many thousands of copies around the world and has been re-printed numerous times. Jim Brown calls it "an authoritative guide for novices and experienced sailors, the best book written on the subject since the early 1990's" 2.) MULTIHULL SEAMANSHIP - Illustrated, by Dr. Gavin LeSueur. Illustrations by Nigel Allison. First published in Australia in 1995, Cyclone Publishers. ISBN 1875181032. Soft cover, spiral bound, large format, 108 pages, black and white. -

ORC Special Regulations Mo3 with Life Raft

ISAF OFFSHORE SPECIAL REGULATIONS Including US Sailing Prescriptions www.ussailing.org Extract for Race Category 4 Multihulls JANUARY 2014 - DECEMBER 2015 © ORC Ltd. 2002, all amendments from 2003 © International Sailing Federation, (IOM) Ltd. Version 1-3 2014 Because this is an extract not all paragraph numbers will be present RED TYPE/SIDE BAR indicates a significant change in 2014 US Sailing extract files are available for individual categories and boat types (monohulls and multihulls) at: http://www.ussailing.org/racing/offshore-big-boats/big-boat-safety-at-sea/special- regulations/extracts US Sailing prescriptions are printed in bold, italic letters Guidance notes and recommendations are in italics The use of the masculine gender shall be taken to mean either gender SECTION 1 - FUNDAMENTAL AND DEFINITIONS 1.01 Purpose and Use 1.01.1 It is the purpose of these Special Regulations to establish uniform ** minimum equipment, accommodation and training standards for monohull and multihull yachts racing offshore. A Proa is excluded from these regulations. 1.01.2 These Special Regulations do not replace, but rather supplement, the ** requirements of governmental authority, the Racing Rules and the rules of Class Associations and Rating Systems. The attention of persons in charge is called to restrictions in the Rules on the location and movement of equipment. 1.01.3 These Special Regulations, adopted internationally, are strongly ** recommended for use by all organizers of offshore races. Race Committees may select the category deemed most suitable for the type of race to be sailed. 1.02 Responsibility of Person in Charge 1.02.1 The safety of a yacht and her crew is the sole and inescapable ** responsibility of the person in charge who must do his best to ensure that the yacht is fully found, thoroughly seaworthy and manned by an experienced crew who have undergone appropriate training and are physically fit to face bad weather. -

Fitting the Unstayed Mast Rig To

ITTING THE UNSTAYED MAST RIG TO YOUR BOAT SOME POPULAR QUESTIONS ANSWERED: - . Will it suit any boat of any hull shape? - Yes, and will particularly aid shallow draft hulls of low ballast ratio as the flexibility of the mast reduces heeling in all conditions. 2. Can it be fitted to multihulls? - Yes, Trimaran installations are similar to monohulls. Catamarans can either have modified bridge decks to obtain sufficient bury of mast or fit a smaller mast in each hull. 3. Can I use my existing stayed rig mast?- No, with the exception of some solid timber Gaff rig masts. 4. Does the mast have to be keel stepped? - Preferably, but it can be fitted in a deck tabernacle. 5. Where is the mast stepped? - Approximately 2 to 4 feet forward of a stayed mast postion. 6. Does it have to be near a bulkhead? - No, as the load transmitted to the deck is not enormous. 7. What structural modifications will I have to make to my boat? - Probably increase the deck strength at the mast by adding:- - for GRP boats more layup of C.S. matt which will be hidden by the head lining under the deck. - for steel, alloy, ferrocement, timber boats, add a deck beam. The mast step only needs to be firmly secured to the keel and no extra reinforcement is necessary to be the boat's keel. - for sheeting to the pushpit, possibly, add a bracing strut across the existing tube, such as a sheet track. 8. How many sails and of what area should be used? - As a general rule:- For boats up to 30 ft., one sail is more ideal. -

A Comparative Evaluation of a Hydrofoil-Assisted Trimaran

COMPARATIVE EVALUATION OF A A HYDROFOIL-ASSISTED TRIMARAN Thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF SCIENCE IN ENGINEERING By Ryno Moolman Supervisor Prof. T.M. Harms Department of Mechanical Engineering University of Stellenbosch Co-supervisor Dr. G. Migeotte CAE Marine December 2005 Declaration I, the undersigned, declare that the work contained in this thesis is my own original work and has not previously, in its entirety or in part, been submitted at any University for a degree. Signature of Candidate Date i Abstract This work is concerned with the design and hydrodynamic aspects of a hydrofoil-assisted trimaran. A design and configuration of a trimaran is evaluated and the performance of a hydrofoil-assisted trimaran is effectively compared to the performance of a hydrofoil-assisted catamaran with similar overall displacement and same speed. The performance of the trimaran with different outrigger clearances are also evaluated and compared. The hydrodynamic aspects focuses mainly on the performance and to a lesser extend on the sea-keeping and stability of a hydrofoil-assisted trimaran. The results were determined by means of experimental testing, theoretical analysis and numerical analysis. The project was initiated as a result of the success of the hydrofoil-assisted catamarans and due to the fact that there does not exist a hydrofoil-assisted trimaran (to the author’s knowledge) where the main focus of the foils is to significantly reduce the resistance. A brief history, recent developments and associated advantages regarding trimarans are discussed. A complete theoretical model is presented to evaluate the lift and drag of the hydrofoils, as well as, the resistance of the trimaran. -

TAHITI DOUCHE When Development Is No Longer Possible, Change Intervenes, Said Alain Gliksman

44-47 Patrimoine_MM147-US:PATRIMOINE 10/05/11 13:59 Page 44 HERITAGE The last of the big proas: TAHITI DOUCHE When development is no longer possible, change intervenes, said Alain Gliksman. This change gave us the craziest boats in nautical history: the proas. Here is the story of the last of these big boats... By Philippe Echelle In 1979-80, we believed we ROSIERE’s capsize on the start sailing and offshore racing. With was also the only French free- could already evaluate the deve- line of the ’82 Rhum signalled Michel Malinovski, he establi- lance journalist at the start of lopment of multihulls, and the the end of the match, and the shed the profession of journalist- 1960 Transat. The touch at the perspective of twenty years of proas were no longer allowed in tester. From Bateaux magazine helm, honed by heroic RORC western re-discovery led us to transatlantic races. On reflection, to editor in chief of Neptune, this races, and Olympic selections in believe that the next victory it is quite probable that all of gifted, meticulous dandy embo- the Flying Dutchman class, an would reward an inevitably revo- these boats lacked, not inge- died the position of the man of incisive pen and eye, a sharp lutionary machine. The proa nuity, but preparation and perfec- the sea. Flirting with being unfo- tooth; Alain was as comfortable concept was ready and waiting ting. The saga of the biggest sur- cussed, the romantic adventurer in editorial meetings or celebrity in the wings, and we witnessed vivor illustrates this era of pio- a creative proliferation. -

The Practical Design of Advanced Marine Vehicles

The Practical Design of Advanced Marine Vehicles By: Chris B. McKesson, PE School of Naval Architecture and Marine Engineering College of Engineering University of New Orleans 2009 Version: Fall 2009 rev 0 This work sponsored by: US Office of Naval Research Grant No: N00014‐09‐1‐0145 1 2 CONTENTS 1 Summary & Purpose of this Textbook ................................................................................................ 27 1.1 Relationship of the Course to Program Outcomes ..................................................................... 28 1.2 Prerequisites ............................................................................................................................... 28 1.3 Resources .................................................................................................................................... 28 1.3.1 Numbered references cited in the text ................................................................................. 29 1.3.2 Important references not explicitly cited in the text ............................................................ 31 1.3.3 AMV Web Resources ............................................................................................................. 32 1.3.4 AMV Design Agents ............................................................................................................... 32 1.3.5 AMV Builders ......................................................................................................................... 33 2 A Note on Conventions ...................................................................................................................... -

Teori Dan Panduan Praktis

TEORI DAN PANDUAN PRAKTIS HIDRODINAMIKA KAPAL HUKUM ARCHIMEDES Penulis Bagiyo Suwasono Ali Munazid Rodlitul Awwalin G.A.P. Poundra Sutiyo i Hang Tuah University Press ii TEORI DAN PANDUAN PRAKTIS HIDRODINAMIKA KAPAL HUKUM ARCHIMEDES iii Sanksi Pelanggaran Pasal 113 Undang-Undang No. 28 Tahun 2014 Tentang Hak Cipta 1. Setiap Orang yang dengan tanpa hak melakukan pelanggaran hak ekonomi sebagaimana dimaksud dalam Pasal 9 ayat (1) huruf i untuk Penggunaan Secara Komersial dipidana dengan pidana penjara paling lama 1 (satu) tahun dan/atau pidana denda paling banyak Rp. 100.000.000,- (Seratus juta rupiah). 2. Setiap Orang yang dengan tanpa hak dan/atau tanpa izin Pencipta atau pemegang Hak Cipta melakukan pelanggaran hak ekonomi Pencipta sebagaimana dimaksud dalam Pasal 9 ayat (1) huruf c, huruf d, huruf f, dan/atau huruf h untuk Penggunaan Secara Komersial dipidana dengan pidana penjara paling lama 3 (tiga) tahun dan/atau pidana denda paling banyak Rp. 500.000.000,- (lima ratus juta rupiah). 3. Setiap Orang yang dengan tanpa hak dan/atau tanpa izin Pencipta atau pemegang Hak Cipta melakukan pelanggaran hak ekonomi Pencipta sebagaimana dimaksud dalam Pasal 9 ayat (1) huruf a, huruf b, huruf e, dan/atau huruf g untuk Penggunaan Secara Komersial dipidana dengan pidana penjara paling lama 4 (empat) tahun dan/atau pidana denda paling banyak Rp. 1.000.000.000,- (satu miliar rupiah). 4. Setiap Orang yang memenuhi unsur sebagaimana dimaksud pada ayat (3) yang dilakukan dalam bentuk pembajakan, dipidana dengan pidana penjara paling lama 10 (sepuluh) tahun dan/atau pidana denda paling banyak Rp. 4.000.000.000,- (empat miliar rupiah) iv TEORI DAN PANDUAN PRAKTIS HIDRODINAMIKA KAPAL HUKUM ARCHIMEDES Oleh: Bagiyo Suwasono Ali Munazid Rodlitul Awwalin G.A.P. -

Sail Power and Performance

the area of Ihe so-called "fore-triangle"), the overlapping part of headsail does not contribute to the driving force. This im plies that it does pay to have o large genoa only if the area of the fore-triangle (or 85 per cent of this area) is taken as the rated sail area. In other words, when compared on the basis of driving force produced per given area (to be paid for), theoverlapping genoas carried by racing yachts are not cost-effective although they are rating- effective in term of measurement rules (Ref. 1). In this respect, the rating rules have a more profound effect on the plan- form of sails thon aerodynamic require ments, or the wind in all its moods. As explicitly demonstrated in Fig. 2, no rig is superior over the whole range of heading angles. There are, however, con sistently poor performers such ns the La teen No. 3 rig, regardless of the course sailed relative to thewind. When reaching, this version of Lateen rig is inferior to the Lateen No. 1 by as rnuch as almost 50 per cent. To the surprise of many readers, perhaps, there are more efficient rigs than the Berntudan such as, for example. La teen No. 1 or Guuter, and this includes windward courses, where the Bermudon rig is widely believed to be outstanding. With the above data now available, it's possible to answer the practical question: how fast will a given hull sail on different headings when driven by eoch of these rigs? Results of a preliminary speed predic tion programme are given in Fig. -

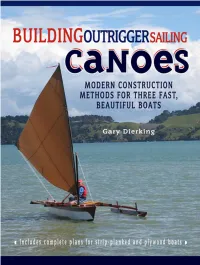

Building Outrigger Sailing Canoes

bUILDINGOUTRIGGERSAILING CANOES INTERNATIONAL MARINE / McGRAW-HILL Camden, Maine ✦ New York ✦ Chicago ✦ San Francisco ✦ Lisbon ✦ London ✦ Madrid Mexico City ✦ Milan ✦ New Delhi ✦ San Juan ✦ Seoul ✦ Singapore ✦ Sydney ✦ Toronto BUILDINGOUTRIGGERSAILING CANOES Modern Construction Methods for Three Fast, Beautiful Boats Gary Dierking Copyright © 2008 by International Marine All rights reserved. Manufactured in the United States of America. Except as permitted under the United States Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher. 0-07-159456-6 The material in this eBook also appears in the print version of this title: 0-07-148791-3. All trademarks are trademarks of their respective owners. Rather than put a trademark symbol after every occurrence of a trademarked name, we use names in an editorial fashion only, and to the benefit of the trademark owner, with no intention of infringement of the trademark. Where such designations appear in this book, they have been printed with initial caps. McGraw-Hill eBooks are available at special quantity discounts to use as premiums and sales promotions, or for use in corporate training programs. For more information, please contact George Hoare, Special Sales, at [email protected] or (212) 904-4069. TERMS OF USE This is a copyrighted work and The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. (“McGraw-Hill”) and its licensors reserve all rights in and to the work. Use of this work is subject to these terms. Except as permitted under the Copyright Act of 1976 and the right to store and retrieve one copy of the work, you may not decompile, disassemble, reverse engineer, reproduce, modify, create derivative works based upon, transmit, distribute, disseminate, sell, publish or sublicense the work or any part of it without McGraw-Hill’s prior consent. -

Monohull Vs Catamaran

MONOHULL VS CATAMARAN Who do you trust? The boating press? They have obligations to their advertisers. Did you ever see a bad boat review? Your friendly Boat Broker/Dealer? Why do their positions seem so aligned with their products? They sell Catamarans only? They’re the best. They sell monohulls only? They’re the best. How about your friend whose HEARD THINGS. But who has sailed monohulls for the last 20 years. He can certainly tell you about those Catamarans! We sell and sail both Catamarans and Monohulls. We run charter companies featuring both. We hire captains who deliver both. Visit factories for both. Talk to designers for both. This presentation will be based on our experiences with both types of boats. We sell both about equally and have little to gain promoting one over the other. In addition to our personal experiences, I will relate what we’re told by transatlantic delivery captains. By owners and charterers. By designers. I firmly believe that when something is right, it makes perfect sense. I hope that you will find that this discussion makes sense. In the end, you have to decide WHAT MAKES SENSE. In this presentation, I’m talking strictly about boats that make sense for living aboard and offshore sailing. Not daysailors. Not racers. Serious cruisers… As I advocate or negate each category I switch hats. Talking from that camps point of view, but modifying my remarks with our personal experience. In all cases we assume a well designed state of the art boat oriented towards our purposes mentioned above. -

Evaluating Modern Catamarans

Evaluating Modern Catamarans Dave & Sherry McCampbell www.SVSoggypaws.com/ 1 Presentations Update 12/7/15 SV Soggy Paws Florida to the Philippines 2 Introduction • 20 years ago - 1996 – 1981 CSY 44 WT my first BW cruiser – needed work, but retired w/ time • 3 years ago - 2013 – 40 K nm, sailed around Carib and across Pacific – I wanted less maintenance & motion & more room – Sherry wanted comfortable computer/office space & more speed – we started looking at cats as possible future boat 3 Introduction • Problems – – find suitable boat at reasonable price in 3rd world – get both boats together to transfer our stuff – sell CSY at reasonable price • 6 months ago – Jun 2015 – SF 44 came on market in W Malaysia – went to see it, then bought it – 2000 nm shakedown trip to PI through terrorist box 4 Outline • Blue Water Cruising Boat Features • Monohulls vs Catamarans • Catamaran History • Some Things We Learned • Explaining Important Cat Characteristics • Evaluating Common Cat Features • References & Cautions • End 5 Our Desirable Blue Water Cruising Boat Features • Suitable for long distance voyaging • Comfortable for extended living aboard • Substantial load carrying capacity • Safe at sea or at anchor in a storm • Substantial fuel & water capacity • Strong quality build • Reasonable draft < 6’ • Reasonable Mom/Pop size - 40-47’ • Affordable cost 6 Monohulls vs Catamarans 7 Monohulls vs Catamarans • 2000 nm Shakedown Observations • Internet List of Advantages and Drawbacks • Safety • Speed • Volume & Windage • Price • Comfort • Draft • Appearance