Polynesian Origins and Migrations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mānoa Heritage Center

Mānoa Heritage Center Teacher’s Information and Resources Kūka‘ō‘ō Heiau Table of Contents Introduction………………………………………………………….……..3 Background Information for Teachers…………………………….….4-10 Mana, Kapu and Heiau…………………………………………….…11-12 Oli……………………………………………………………………….…13 Secondary Sources………………………………………………………..14 Mānoa Valley Timeline (Secondary Source)…………………………….14-18 Timeline Activities…………………………………………………….18-20 Primary Sources………………………………………………………20-21 Oral traditions: Kapunahou I (Primary Sources)……………….……...22-23 Suggested Questions for Kapunahou I………………………………….24 Oral traditions: Kapunahou II (Primary sources) ……………………..25-26 Suggested questions for Kapunahou II…………………………………27 Oral History: A Walk Through Old Mānoa (Primary Source)………..28-31 1820 Map and Activities (Primary Source)…………………………………31 DOE Standards……………………………………………………….32-35 About the Mānoa Heritage Center……………………………………...36 Planning Your Visit………………………………………………………37 2 Kōnāhuanui Introduction In the heart of Mānoa valley, the Mānoa Heritage Center invites you to step back in time and explore our living connections to Hawai‘i‘s past. Kūka‘ō‘ō stands as the last intact walled heiau in the greater ahupua‘a of Waikīkī. Believed to have been built by Menehune, the heiau is interpreted today as an agricultural temple. Surrounding the heiau are native Hawaiian gardens that feature an extraordinary collection of rare and endangered species, as well as plants introduced by Polynesian settlers. Our site also tells the story of Mānoa valley, once a rich agricultural area that Hawaiians farmed for centuries. Foreign contact brought many changes to the valley including immigrant resident farmers from various ethnic groups. Today Mānoa is known as one of the most desirable residential areas in Hawai‘i, but its strong sense of place endures. 3 Background Information for Teachers Mānoa Valley As part of the Ko‘olau range, the large amphitheater valley of Mānoa was carved out through wind, rain and erosion. -

Visibility Analysis of Oahu Heiau

Visibility Analysis of Oahu Heiau A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN GEOGRAPHY May 2012 By Kepa Lyman Thesis Committee: Matthew McGranaghan, Chair Hong Jiang William Chapman Keywords: heiau, intervisibility, viewshed analysis Table of Contents LIST OF FIGURES .................................................................................................................................... III LIST OF TABLES ...................................................................................................................................... IV INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................ 5 CHAPTER OUTLINE ..................................................................................................................................... 6 CHAPTER I. HAWAIIAN HEIAU ............................................................................................................ 8 HEIAU AS SYMBOL ..................................................................................................................................... 8 HEIAU AS FORTRESS ................................................................................................................................. 12 TYPES ...................................................................................................................................................... -

Na Makua Mahalo Ia. Mormon Influences on Hawaiian Music and Dance

2 john kamealoha almeida called the dean of hawaiian composers for of hawaiian compositions although he Is pure portuguese na makua mahalo laia hormonmormon influences on hawaiian music and dance his thousands many of his songs are now classics probably the mostroostmoost popular being 6 sk 11 bt T lesu heme ke kanakakekanakaKe waiwai has been blind since the age of ten but was very helpful in raising money for the church through luaus and hula when the na makua mahalo laia awards were first envisioned it was intended shows throughout the 1930s and 1940s he is presently eightsixeight six years that their scope would remain limited to basically LDSLOS people who had disting- 190s old uished themselves in the performing arts for various reasons it has not been possible to retain this earlier restricted focus of the awards As a alice namakelua aunty is 90 years young and is remarkably spry and result even though recipients tend to be mainly drawn from LDSLOS ranks church active in her days she was a singer dancer translator composer membership is not the prime criterion for selection rather recipients are lecturer genealogist and slackstacksiacksiecksleckslackkeystackkeykey guitar artist she had a best- judged on the depth and quality of the contributions they have made to the selling album when she was eightytwoeighty two years old and still attends hawaiian cultural community an examination of the two sets of recipients church functions as best as she can she studledstudiedstudded hawaiian music for might better illustrate the criteria -

Meroz-Plank Canoe-Edited1 Without Bold Ital

UC Berkeley Survey Reports, Survey of California and Other Indian Languages Title The Plank Canoe of Southern California: Not a Polynesian Import, but a Local Innovation Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1977t6ww Author Meroz, Yoram Publication Date 2013 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Plank Canoe of Southern California: Not a Polynesian Import, but a Local Innovation YORAM MEROZ By nearly a millennium ago, Polynesians had settled most of the habitable islands of the eastern Pacific, as far east as Easter Island and as far north as Hawai‘i, after journeys of thousands of kilometers across open water. It is reasonable to ask whether Polynesian voyagers traveled thousands of kilometers more and reached the Americas. Despite much research and speculation over the past two centuries, evidence of contact between Polynesia and the Americas is scant. At present, it is generally accepted that Polynesians did reach South America, largely on the basis of the presence of the sweet potato, an American cultivar, in prehistoric East Polynesia. More such evidence would be significant and exciting; however, no other argument for such contact is currently free of uncertainty or controversy.1 In a separate debate, archaeologists and ethnologists have been disputing the rise of the unusually complex society of the Chumash of Southern California. Chumash social complexity was closely associated with the development of the plank-built canoe (Hudson et al. 1978), a unique technological and cultural complex, whose origins remain obscure (Gamble 2002). In a recent series of papers, Terry Jones and Kathryn Klar present what they claim is linguistic, archaeological, and ethnographical evidence for prehistoric contact from Polynesia to the Americas (Jones and Klar 2005, Klar and Jones 2005). -

Wao Kele O Puna Comprehensive Management Plan

Wao Kele o Puna Comprehensive Management Plan Prepared for: August, 2017 Prepared by: Nālehualawaku‘ulei Nālehualawaku‘ulei Nā-lehua-lawa-ku‘u-lei is a team of cultural resource specialists and planners that have taken on the responsibilities in preparing this comprehensive management for the Office of Hawaiian Affairs. Nā pua o kēia lei nani The flowers of this lovely lei Lehua a‘o Wao Kele The lehua blossoms of Wao Kele Lawa lua i kēia lei Bound tightly in this lei Ku‘u lei makamae My most treasured lei Lei hiwahiwa o Puna Beloved lei of Puna E mālama mākou iā ‘oe Let us serve you E hō mai ka ‘ike Grant us wisdom ‘O mākou nā pua For we represent the flowers O Nālehualawaku‘ulei Of Nālehualawaku‘ulei (Poem by na Auli‘i Mitchell, Cultural Surveys Hawai‘i) We come together like the flowers strung in a lei to complete the task put before us. To assist in the preservation of Hawaiian lands, the sacred lands of Wao Kele o Puna, therefore we are: The Flowers That Complete My Lei Preparation of the Wao Kele o Puna Comprehensive Management Plan In addition to the planning team (Nālehualawaku‘ulei), many minds and hands played important roles in the preparation of this Wao Kele o Puna Comprehensive Management Plan. Likewise, a number of support documents were used in the development of this plan (many are noted as Appendices). As part of the planning process, the Office of Hawaiian Affairs assembled the ‘Aha Kūkā (Advisory Council), bringing members of the diverse Puna community together to provide mana‘o (thoughts and opinions) to OHA regarding the development of this comprehensive management plan (CMP). -

Patterns in the Art of Samoan Siapo

The art of Samoan Siapo By Paul Tauiliili EDCS 606 with Dr. Don Rubinstein Dr. Sandy Dawson Dr. Neil Pateman Dr. Joe Zilliox Source: (Neich & Pendagrast 1997) 1 Table of Contents Introduction: Cultural Significance 3 Methodology How did you conduct your research 7 Interview questions used 9 Difficulties encountered 10 Is research complete 10 Description What is siapo? 11 How is siapo designed 16 SIAPO ELEI 16 Elei process 18 Identifying imprints and patterns 20 Sequences of Imprints 23 Imprints used as standard of measurement Length and width 25 Surface area 27 Congruency 28 Balance defined 30 SIAPO MAMANU 31 Mamanu process 32 Mamanu or motifs 34 Symmetry classifications 36 Horizontal and vertical symmetry 37 Translations 41 180 degree rotation 44 Conclusion 45 References 46 2 Introduction This paper is focused on describing the rich art of siapo making in Samoa and the mathematical concepts derived from its designs and production. It begins with a historical look at siapo in the Samoan culture and the methods used to conduct this research. It is followed by a detailed description of how Samoan siapo is processed from raw bark to finished work of art and the differences between two distinct types of Samoan siapo: a) siapo elei and b) siapo mamanu. And finally it focuses on exploring the mathematics involved in the art of Samoan siapo. Cultural Significance Siapo is a Samoan word for tapa or bark cloth that has been painted or imprinted with various design motifs. Although Samoan siapo can be distinctly recognized as a pure art form that flourishes in Samoa its origins can be traced to eastern Asia (Neich & Pendagrast, 1997). -

Polyvocal Tongan Barkcloths: Contemporary Ngatu and Nomenclature at the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

Tuhinga 24: 85–104 Copyright © Te Papa Museum of New Zealand (2013) Polyvocal Tongan barkcloths: contemporary ngatu and nomenclature at the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa Billie Lythberg Mira Szászy Research Centre for Mäori and Pacific Economic Development, University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand ([email protected]) ABSTRACT: The Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa (Te Papa) collects and exhibits Tongan barkcloth (ngatu) to illustrate curatorial narratives about Pacific peoples in New Zealand. I discuss the materiality and provenances of five ngatu at Te Papa, their trajectories into the museum’s Pacific Cultures collection and, where relevant, how they have been exhibited. I consider the role of Tongan curators and communities in determining how, when and which ngatu will enter the collection, and how Tongan identity will be imaged by the objects. The paper concludes with a close examination of contemporary descriptive and evaluative nomenclature for ngatu made with synthetic materials, including examples at Te Papa. KEYWORDS: Te Papa, Pacific Cultures collection, ngatu, barkcloths, Tonga, New Zealand, nomenclature. Introduction values by Polynesians, the ways in which Polynesian and Western popular culture have melded, and also the The Pacific Cultures collection at the Museum of New possibilities presented by these transactions (Refiti 1996: Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa (Te Papa) includes Tongan bark- 124).1 As well as being a literal descriptor of the multiple cloths (ngatu) representative of material and technological and overlapping Tongan systems of nomenclature for innovation, significant historical events, and the confluence contempo rary ngatu (see Table 1), the term polyvocal encom- of seemingly divergent Tongan and museological politics passes the many voices employed to talk about bark- of prestige. -

The Conflict Between Traditional Knowledge and Modernity in the Navigation of Polynesia

Journal of World Anthropology: Occasional Papers: Volume III, Number 2 48 “When earth and sky almost meet”: The Conflict between Traditional Knowledge and Modernity in Polynesian Navigation. Luke Strongman1 Abstract This paper provides an account of the differing ontologies of Polynesian and European navigation techniques in the Pacific. The subject of conflict between traditional knowledge and modernity is examined from nine points of view: The cultural problematics of textual representation, historical differences between European and Polynesian navigation; voyages of re-discovery and re-creation: Lewis and Finney; How the Polynesians navigated in the Pacific; a European history of Polynesian navigation accounts from early encounters; “Earth and Sky almost meet”: Polynesian literary views of recovered knowledge; lost knowledge in cultural exchanges – the parallax view; contemporary views and lost complexities. Introduction Polynesians descended from kinship groups in south-east Asia discovered new islands in the Pacific in the Holocene period, up to 5000 calendar years before the present day. The European voyages of discovery in the Pacific from the eighteenth century, in the Anthropocene era, brought Polynesian and European cultures together, resulting in exchanges that threw their cross-cultural differences into relief. As Bernard Smith suggests: “The scientific examination of the Pacific, by its very nature, depended on the level reached by the art of navigation” (Smith 1985:2). Two very different cultural systems, with different navigational practices, began to interact. 1 The Open Polytechnic of New Zealand Journal of World Anthropology: Occasional Papers: Volume III, Number 2 49 Their varied cultural ontologies were based on different views of society, science, religion, history, narrative, and beliefs about the world. -

June Program Guide

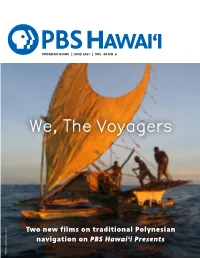

PROGRAM GUIDE | JUNE 2021 | VOL. 40 NO. 6 Two new films on traditional Polynesian navigation on PBS Hawai‘i Presents Wade Fairley, copyright Vaka Taumako Project Taumako copyright Vaka Fairley, Wade A Long Story That Informed, Influenced STATEWIDE BOARD OF DIRECTORS and Inspired Chair The show’s eloquent description Joanne Lo Grimes nearly says it all… Vice Chair Long Story Short with Leslie Wilcox Jason Haruki features engaging conversations with Secretary some of the most intriguing people in Joy Miura Koerte Hawai‘i and across the world. Guests Treasurer share personal stories, experiences Kent Tsukamoto and values that have helped shape who they are. Muriel Anderson What it does not express is the As we continue to tell stories of Susan Bendon magical presence Leslie brought to Hawai‘i’s rich history, our content Jodi Endo Chai will mirror and reflect our diverse James E. Duffy Jr. each conversation and the priceless communities, past, present and Matthew Emerson collection of diverse voices and Jason Fujimoto untold stories she captured over the future. We are in the process of AJ Halagao years. Former guest Hoala Greevy, redefining some of our current Ian Kitajima Founder and CEO of Paubox, Inc., programs like Nā Mele: Traditions in Noelani Kalipi may have said it best, “Leslie was Hawaiian Song and INSIGHTS ON PBS Kamani Kuala‘au HAWAI‘I, and soon we will announce Theresia McMurdo brilliant to bring all of these pieces Bettina Mehnert of Hawai‘i history together to live the name and concept of a new series. Ryan Kaipo Nobriga forever in one amazing library. -

By Dylan Rose

TheULTIMATE ATOLL A Saltwater Utopia for the Adventuresome Angler by Dylan Rose he moment I set foot on Christmas Island my life was changed forever. My first visit was a metaphorical abstraction of the island’s vibe, culture, warmth and relaxed pace. As I stepped off of the big Fiji Airways 737 onto the tarmac I noticed from Tbehind the airport fence a small gathering of villagers quietly watching us deplane. Some of the island’s sun-kissed, bronzed-faced children were standing behind the chain link fence, smiling and waving excitedly. I Dylan Rose tracks a GT that turned to look behind me expecting to see a familiar party waving back, was spotted from the boat. but I soon realized their brilliant white smiles were actually for me and my Photo: Brian Gies intrepid gang of arriving fly anglers. PAGE 1 The ULTIMATE ATOLL Of all the places I’ve traveled, the feeling of being truly welcome in a the Pacific Ocean. Captain Cook landed on the island on Christmas Eve in foreign land is the strongest at Christmas Island. It’s the attribute about the 1777 and I can only imagine what a great holiday it might have been if he had place that connects me most to it. It’s baffling to me how a locale so far packed an 8-weight and a few Gotchas. away and different from anything I know can somehow still feel so much Blasted by high altitude, British H-bomb testing in the late 1950s and like home. From the giddy bouncing children swimming in the boat harbor again by the United States in the 1960s, Christmas Island and its magnificent to the villagers tending their chores; to the guides and their families, the lodge population of seabirds got a front row view of the inception of the atomic age. -

The Canoe Is the People LEARNER's TEXT

The Canoe Is The People LEARNER’S TEXT United Nations Local and Indigenous Educational, Scientific and Knowledge Systems Cultural Organization Learnerstxtfinal_C5.indd 1 14/11/2013 11:28 The Canoe Is the People educational Resource Pack: Learner’s Text The Resource Pack also includes: Teacher’s Manual, CD–ROM and Poster. Produced by the Local and Indigenous Knowledge Systems (LINKS) Programme, UNESCO www.unesco.org/links Published in 2013 by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization 7, place de Fontenoy, 75352 Paris 07 SP, France ©2013 UNESCO All rights reserved The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNESCO concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The ideas and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors; they are not necessarily those of UNESCO and do not commit the Organization. Coordinated by Douglas Nakashima, Head, LINKS Programme, UNESCO Author Gillian O’Connell Printed by UNESCO Printed in France Contact: Douglas Nakashima LINKS Programme UNESCO [email protected] 2 The Canoe Is the People: Indigenous Navigation in the Pacific Learnerstxtfinal_C5.indd 2 14/11/2013 11:28 contents learner’s SECTIONTEXT 3 The Canoe Is the People: Indigenous Navigation in the Pacific Learnerstxtfinal_C5.indd 3 14/11/2013 11:28 Acknowledgements The Canoe Is the People Resource Pack has benefited from the collaborative efforts of a large number of people and institutions who have each contributed to shaping the final product. -

39Th Annual North Shore Menehune Surfing Championships

IS BUGG “E Ala Na Moku Kai Liloloa” • D AH S F W R E E In This Issue E N ! E • Waimea Valley Makahiki Festival • Page 3 R S O I Cholo's 20 Year Anniversary • Page 9 N H C S Aloha Aina Recycling • Page 13 E H 1 T Harvest Festival • Page 14 9 R 7 O 0 Menehune Surf Contest Entry Form • Page 16 N Photo: Courtesy of Menehune Surf Contest NORTH SHORE NEWS September 30, 2015 VOLUME 32, NUMBER 20 Photo: Courtesy of Menehune Surf Contest 39th Annual North Shore Menehune Surfing Championships The 39th Annual North highlight of the contest is the Kokua I Love The Menehune.” Entries are Shore Menehune Surfing Cham- Division for keiki 3-6. This division due Oct. 1st by mail or they can pionships will be held on October is non competitive, parents are be hand delivered to Surf N Sea in 17, 18, 24, 25, 2015 at Hale‘iwa allowed to assist in the water and Hale‘iwa. For more information or Ali‘i Beach Park. This contest is for every keiki receives a trophy. Keiki if you would like to contribute to keiki 3-12 years old. Keiki can sign can bring a gently used book and this event contact Contest Director up for Divisions in Longboard and swap it out for another in the 3rd Ivy @ [email protected]. Mahalo Shortboard. Annual Menehune Book Exchange. Nui to all our 2015 Menehune They can also participate in This is our way of promoting lit- sponsors! We are grateful for your an Expression Session in SUP and eracy in our young surfers.