Creatureliness

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Librib 501200.Pdf

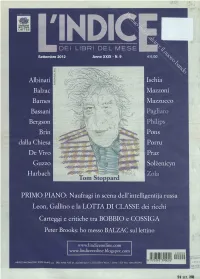

FONDAZIONE BOTTARI LATTES Settembre 2012 Anno XXIX - N. 9 Albinati Ischia Balzac Mazzoni Barnes Mazzucco Bassani Bergson Brin Pons dalla Chiesa Porru De Vivo Praz Guzzo Solzenicyn Harbach PRIMO PIANO: Naufragi in scena del?intelligenti)a russa Leon, Gallino e la LOTTA DI CLASSE dei ricchi Carteggi e critiche tra BOBBIO e COSSIGA Peter Brooks: ho messo BALZAC sul lettino www.lindiceonline.com www.lindiceonline.blogspot.com MENSILE D'INFORMAZIONE - POSTE ITALIANE s.p.a. - SPED. IN ABB. POST. D.L. 353/2003 (conv.in L. 27/02/2004 n° 46) art. I, comma ], DCB Torino - ISSN 0393-3903 Editoria La verità è destabilizzante Per Achille Erba di Lorenzo Fazio Quando è mancato Achille Erba, uno dei fon- ferimento costante al Vaticano II e all'episcopa- a domanda è: "Ma ci quere- spezzarne il meccanismo di pro- datori de "L'Indice", alcune persone a lui vicine to di Michele Pellegrino) sono ampiamente illu- Lleranno?". Domanda sba- duzione e trovare (provare) al- hanno deciso di chiedere ospitalità a quello che lui strate nel sito www.lindiceonline.com. gliata per un editore che si pre- tre verità. Come editore di libri, ha continuato a considerare Usuo giornale - anche È opportuna una premessa. Riteniamo si sarà figge il solo scopo di raccontare opera su tempi lunghi e incrocia quando ha abbandonato l'insegnamento universi- tutti d'accordo che le analisi e le discussioni vol- la verità. Sembra semplice, ep- passato e presente avendo una tario per i barrios di Santiago del Cile e, successi- te ad illustrare e approfondire nei suoi diversi pure tutta la complessità del la- prospettiva anche storica e più vamente, per una vita concentrata sulla ricerca - aspetti la ricerca storica di Achille e ad indivi- voro di un editore di saggistica libera rispetto a quella dei me- allo scopo di convocare un'incontro che ha lo sco- duare gli orientamenti generali che ad essa si col- di attualità sta dentro questa pa- dia, che sono quotidianamente po di ricordarlo, ma anche di avviare una riflessio- legano e che eventualmente la ispirano non pos- rola. -

Heteroglossia N

n. 14 eum x quaderni Andrea Rondini Heteroglossia n. 14| 2016 pianeta non-fiction a cura di Andrea Rondini heteroglossia Heteroglossia Quaderni di Linguaggi e Interdisciplinarità. eum edizioni università di macerata > 2006-2016 Dipartimento di Scienze Politiche, della Comunicazione e delle Relazioni Internazionali. isbn 978-88-6056-487-0 edizioni università di macerata eum x quaderni n. 14 | anno 2016 eum eum Heteroglossia n. 14 Pianeta non-fiction a cura di Andrea Rondini eum Università degli Studi di Macerata Heteroglossia n. 14 Quaderni di Linguaggi e Interdisciplinarità. Dipartimento di Scienze Politiche, della Comunicazione e delle Relazioni Internazionali Direttore: Hans-Georg Grüning Comitato scientifico: Mathilde Anquetil (segreteria di redazione), Alessia Bertolazzi, Ramona Bongelli, Ronald Car, Giorgio Cipolletta, Lucia D'Ambrosi, Armando Francesconi, Hans- Georg Grüning, Danielle Lévy, Natascia Mattucci, Andrea Rondini, Marcello Verdenelli, Francesca Vitrone Comitato di redazione: Mathilde Anquetil (Università di Macerata), Alessia Bertolazzi (Università di Macerata), Ramona Bongelli (Università di Macerata), Edith Cognigni (Università di Macerata), Lucia D'Ambrosi (Università di Macerata), Lisa Block de Behar (Universidad de la Republica, Montevideo, Uruguay), Madalina Florescu (Universidade do Porto, Portogallo), Armando Francesconi (Università di Macerata), Aline Gohard-Radenkovic (Université de Fribourg, Suisse), Karl Alfons Knauth (Ruhr-Universität Bochum), Claire Kramsch (University of California Berkeley), Hans-Georg -

Cahiers D'études Italiennes, 7

Cahiers d’études italiennes Novecento... e dintorni 7 | 2008 Images littéraires de la société contemporaine (3) Images et formes de la littérature narrative italienne des années 1970 à nos jours Alain Sarrabayrousse et Christophe Mileschi (dir.) Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/cei/836 DOI : 10.4000/cei.836 ISSN : 2260-779X Éditeur UGA Éditions/Université Grenoble Alpes Édition imprimée Date de publication : 15 mai 2008 ISBN : 978-2-84310-121-2 ISSN : 1770-9571 Référence électronique Alain Sarrabayrousse et Christophe Mileschi (dir.), Cahiers d’études italiennes, 7 | 2008, « Images littéraires de la société contemporaine (3) » [En ligne], mis en ligne le 15 novembre 2009, consulté le 19 mars 2021. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/cei/836 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/cei.836 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 19 mars 2021. © ELLUG 1 SOMMAIRE Avant-propos Christophe Mileschi Il rombo dall’«Emilia Paranoica». Altri libertini di Tondelli Matteo Giancotti Meditazione sulla diversità e sulla «separatezza» in Camere separate di Pier Vittorio Tondelli Chantal Randoing Invention de la différence et altérité absolue dans l’œuvre de Sebastiano Vassalli Lisa El Ghaoui La religion juive ou la découverte de l’altérité dans La parola ebreo de Rosetta Loy Judith Lindenberg La sorcière comme image de la différence dans La chimera de Vassalli Stefano Magni La figure du juif dans La Storia d’Elsa Morante Sophie Nezri-Dufour Fra differenza e identità microcosmo e ibridismo in alcuni romanzi di Luigi Meneghello Tatiana Bisanti Spazialità e nostos in La festa del ritorno di Carmine Abate Alfredo Luzi L’île partagée. -

Heteroglossia N

n. 14 eum x quaderni Andrea Rondini Heteroglossia n. 14| 2016 pianeta non-fiction a cura di Andrea Rondini heteroglossia Heteroglossia Quaderni di Linguaggi e Interdisciplinarità. eum edizioni università di macerata > 2006-2016 Dipartimento di Scienze Politiche, della Comunicazione e delle Relazioni Internazionali. isbn 978-88-6056-487-0 edizioni università di macerata eum x quaderni n. 14 | anno 2016 eum eum Heteroglossia n. 14 Pianeta non-fiction a cura di Andrea Rondini eum Università degli Studi di Macerata Heteroglossia n. 14 Quaderni di Linguaggi e Interdisciplinarità. Dipartimento di Scienze Politiche, della Comunicazione e delle Relazioni Internazionali Direttore: Hans-Georg Grüning Comitato scientifico: Mathilde Anquetil (segreteria di redazione), Alessia Bertolazzi, Ramona Bongelli, Ronald Car, Giorgio Cipolletta, Lucia D'Ambrosi, Armando Francesconi, Hans- Georg Grüning, Danielle Lévy, Natascia Mattucci, Andrea Rondini, Marcello Verdenelli, Francesca Vitrone Comitato di redazione: Mathilde Anquetil (Università di Macerata), Alessia Bertolazzi (Università di Macerata), Ramona Bongelli (Università di Macerata), Edith Cognigni (Università di Macerata), Lucia D'Ambrosi (Università di Macerata), Lisa Block de Behar (Universidad de la Republica, Montevideo, Uruguay), Madalina Florescu (Universidade do Porto, Portogallo), Armando Francesconi (Università di Macerata), Aline Gohard-Radenkovic (Université de Fribourg, Suisse), Karl Alfons Knauth (Ruhr-Universität Bochum), Claire Kramsch (University of California Berkeley), Hans-Georg -

E La Voce Della Poesia Mario Luzi

INSERTO DELLA RIVISTA COMUNITÀITALIANA - REALIZZATO IN COLLABORAZIONE CON I DIPARTIMENTI DI ITALIANO DELLE UNIVERSITÀ PUBBLicHE BRASILIANE ano VII - numero 77 ano Não pode ser vendido separadamente. Não pode ser vendido . Comunità Italiana Suplemento da Revista Mario Luzi e la voce della poesia Maggio / 2010 Editora Comunità Rio de Janeiro - Brasil www.comunitaitaliana.com n omaggio a Mario Luzi, tra i più grandi poeti italiani del [email protected] secolo, scomparso, ultrà novantenne, nel 2005, riportiamo Direttore responsabile la poesia-colloquio a lui dedicata da Giuseppe Conte, po- Pietro Petraglia I eta contemporaneo ben conosciuto ai lettori di Mosaico, in- Editore troducendo gli articoli e la scelta antologica di quattro giovani Fabio Pierangeli studiosi del poeta fiorentino: Irene Baccarini (Università Tor Grafico Vergata, Roma), Noemi Corcione (Università di Napoli Fede- Alberto Carvalho rico II), Emiliano Ventura (saggista, suo il recente testo Mario COMITATO SCIENTIFICO Luzi, La poesia in teatro, Scienze e Lettere editore), Gabriele Alexandre Montaury (PUC-Rio); Alvaro Ottaviani (Università Tor Vergata, Roma). Santos Simões Junior (UNESP); Andrea Gareffi (Univ. di Roma “Tor Vergata”); Mario, è finito il Novecento Andrea Santurbano (UFSC); Andréia Guerini (UFSC); Anna Palma (UFSC); Cecilia Casini ed è la poesia che non finisce (USP); Cristiana Lardo (Univ. di Roma è la tua fedeltà per quell’aprile- “Tor Vergata”); Daniele Fioretti (Univ. amore che arriva sino al volo delle rondini Wisconsin-Madison); Elisabetta -

La Narrativa Del Novecento Tra Spagna E Italia 1939-1989

La narrativa del Novecento tra Spagna e Italia 1939-1989 Alessandro Ghignoli ([email protected]) UNIVERSIDAD DE MÁLAGA Resumen Palabras clave En nuestro trabajo queremos mostrar Literatura española e italiana como en el período comprendido entre Literatura comparada 1939 y 1989, la narrativa española y la Narrativa italiana han tenido confluencias y Siglo XX momentos de contacto bastante evidentes. Haremos hincapié sobre todo en los procesos históricos y sociales de ambos países para la construcción de sus literaturas. Abstract Key words In this piece of work we want to show Spanish and Italian Literature that there are evident similarities Comparative Literature between the Spanish and Italian Narrative writings produced between the years 20th Century 1939 and 1989, and specifically in the historical and social processes of both countries during the creation of their AnMal Electrónica 39 (2015) literatures. ISSN 1697-4239 1. La Spagna all’inizio del XX secolo soffriva un ritardo sociale e politico, rispetto agli altri paesi europei, di notevole portata, situazione ereditata anche da epoche precedenti. La guerra civile del 1936-39, sarà la finalizzazione di questo periodo in un paese in cui l’unica parvenza di stabilità poteva avvenire sotto una forma di dittatura. Possiamo tranquillamente affermare che quello che successe nell’estate del 1936 fu una conseguenza di lotte secolari interne alla penisola iberica, nel febbraio sempre di quell’anno vi erano in Spagna due blocchi che si scontrarono durante le elezioni politiche, portando alla vittoria il fronte progressista, anche se in maniera abbastanza debole. Tra il 17 e il 18 luglio scoppiò la sollevazione autoritaria dei nazionalisti spagnoli con a capo un uomo che determinerà il futuro 74 Narrativa del Novecento AnMal Electrónica 39 (2015) A. -

Raffaele La Capria È Nato a Napoli Nel 1922, Dove Si È Laureato in Giurisprudenza

Raffaele La Capria è nato a Napoli nel 1922, dove si è laureato in Giurisprudenza. Ha compiuto la sua formazione letteraria soggiornando in Francia, Inghilterra e Stati Uniti. Narratore e saggista, ha collaborato con riviste e quotidiani, tra cui "Il Mondo", "Tempo presente" e il "Corriere della Sera" ed è stato autore di radiodrammi per la Rai. È stato co-sceneggiatore di molti film di Francesco Rosi, tra i quali Le mani sulla città (1963), Uomini contro (1970). Ha esordito con il romanzo Un giorno d'impazienza (1952). Nel 1961 ha vinto il premio Strega con Ferito a morte, ritratto di Napoli che "ti ferisce a morte o t'addormenta", e di una generazione seguita con complessi sbalzi temporali lungo l'arco di un decennio.Nel 1982 ha raccolto i tre romanzi Un giorno d'impazienza, Ferito a morte e Amore e psiche (1973) nel volume Tre romanzi di una giornata. In seguito si è dedicato, con l'eccezione di Fiori giapponesi (1979) e La neve del Vesuvio (1988), a un genere che, anche se con una forte vena narrativa, è molto più vicino alla saggistica. L'argomento di gran parte della sua letteratura è Napoli, vista quasi sempre da lontano poiché l'autore lasciò la sua città in gioventù per trasferirsi a Roma: L'occhio di Napoli del 1994 o Napolitan Graffiti del 1999 sono due esempi significativi, ai quali si aggiunge Capri e non più Capri(1991). Non mancano pagine di riflessione letteraria, o sul mestiere dello scrittore, come Letteratura e salti mortali (1990) o il libro pubblicato da Minimum fax nel 1996, L'apprendista scrittore, in cui prosegue idealmente l'abbozzo di autobiografia letteraria, che aveva cominciato con Un giorno d'impazienza. -

Toronto, Canada: in Versione Cartacea Fino Al 2004, Online Dal 2005)

Anno XXXVI, n. 2 BIBLIOTECA DI RIVISTA DI STUDI ITALIANI Agosto 2018 Tutti i diritti riservati. © 1983 Rivista di Studi Italiani ISSN 1916 - 5412 Rivista di Studi Italiani (Toronto, Canada: in versione cartacea fino al 2004, online dal 2005) IPOGEI DEL MITO, DEL TEATRO E DEL RITO METAFORE DELLO SGUARDO E SEMIOSI DELLO SPAZIO CTONIO A NAPOLI: DA STRABONE E VIRGILIO AGLI SCRITTORI CONTEMPORANEI, NEGLI IPOGEI E NEI FONDACHI DELLA CITTÀ L a fabbrica tufacea della vicereale casa napoletana che si illiquama di mare, cede in alchim ia l’ocra rallegrato del giorno consegnandone i sigilli del calore alla notte e d’argento dolce vivissimo fondendoli dentro un aere di veli moscati di stelle. Ruggero Cappuccio ( Shakespea Re di Napoli , 2002, p. 6 ) CARMELA LUCIA Università di Salerno Riassunto : Il saggio racconta la Napoli più cruda e ferina, costruita su grotte, anfratti, androni oscuri, catacombe, strapiombi di tufo, ‘ bassi fatti apposta per ingoiare chi fugge ’ e antri asfittici, rifugi di diseredati senza qualità. Napoli, lontana dall’oleograf ia della città mediterranea, solare, barocca, è qui una città misteriosa, tufacea, dedalea, porosa, sulfurea, tellurica. Nel suo ‘ ventre ’ si celano: un dedalo di vicoli, oscuri budelli, bassifondi umidi, mefitici ipogei con le loro discese negli inferi del la prostituzione, dei femminielli, degli scarafaggi, dei topi. I suoi bassifondi diventano come tenebrosi angoli di allucinazioni, con una carica greve di impietosa violenza e di ignoto magnetismo, di tensioni e pulsioni dove amore e morte coincidono. Il f ondaco segna infine il limite dell’eccesso della carnalità: il ‘ basso ’ diventa qui un luogo simbolico in cui si concentra la feritas , ai margini della vita in cui si nasconde la ferita della città ormai deforme, diversa, sconosciuta a se stessa. -

Riattivazione Del Premio Letterario IILA a Roberto Fernández Retamar Indice

iila NUOVO PREMIO LETTERATURAiila Riattivazione del Premio Letterario IILA A Roberto Fernández Retamar Indice Introduzione 3 di Donato Di Santo, Segretario Generale IILA Premio Letterario IILA 5 a cura della Segreteria Culturale - Breve storia del Premio - I vincitori 1969-1996 - La giuria - Il logo - Progetto pilota 2019-2020 Galleria degli autori vincitori 10 Biografia di Roberto Fernández Retamar 23 2 Introduzione L’IILA, l’Organizzazione Internazionale Italo-Latino Americana, formata dai governi dell’Italia e di 20 paesi dell’America Latina (Argentina, Bolivia, Brasile, Cile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Messico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Perù, Repubblica Dominicana, Uruguay, Venezuela), sta vivendo la sua “rinascita” anche in ambito culturale. Una delle tappe più importanti di questo percorso, che trae la propria forza evocativa dalle radici stesse dell’IILA, è la riattivazione (dopo ben 23 anni!), del suo prestigioso Premio Letterario. Nelle varie edizioni - dal 1969 al 1996 - sono stati premiati autori del calibro di: José Lezama Lima (Cuba), Juan Carlos Onetti (Uruguay), Jorge Amado (Brasile), Antonio Di Benedetto (Argentina), Manuel Puig (Argentina), Mario Vargas Llosa (Perù), Ignácio de Loyola Brandão (Brasile), Adolfo Bioy Casares (Argentina), Carlos Fuentes (Messico), Álvaro Mutis (Colombia), Augusto Monterroso (Guatemala), Guillermo Cabrera Infante (Cuba), Francisco Coloane (Cile). Di grande valore sono stati anche i vincitori della “Sezione traduttori”, tra cui Francesco Tentori Montalto, Giuliana Segre Giorgi, Pino Cacucci, tra gli altri. Nel corso della storia del Premio, si sono avvicendati nella Giuria personalità come Leonardo Sciascia, Giovanni Macchia, Guido Piovene, Mario Luzi, Dario Puccini, Angelo Maria Ripellino, Carmelo Samonà, tra gli altri. -

Facoltà Di Lettere E Filosofia Dipartimento Di Studi Greco-Latini, Italiani, Scenico-Musicali

FACOLTÀ DI LETTERE E FILOSOFIA DIPARTIMENTO DI STUDI GRECO-LATINI, ITALIANI, SCENICO-MUSICALI DOTTORATO DI RICERCA IN ITALIANISTICA TESI DI DOTTORATO CICLO XXII IL REALISMO NELL’OPERA DI DOMENICO REA: SPACCANAPOLI, RITRATTO DI MAGGIO, QUEL CHE VIDE CUMMEO E UNA VAMPATA DI ROSSORE RELATORE CANDIDATO Prof. Francesco Muzzioli Sayyid Kotb Amin Kotb CORRELATORE Prof. Marcello Carlino ــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــ ANNO ACCADEMICO 2011/2012 - 1 - Il realismo nell’opera di Domenico Rea: Spaccanapoli, Ritratto di maggio, Quel che vide Cummeo e Una vampata di rossore INDICE INTRODUZIONE: REA TRA IL NEOREALISMO E IL MERIDIONALISMO …………… 3 CAPITOLO PRIMO: LA REALTÀ NAPOLETANA E LA SUA SOFFERENZA 1.1- Il mondo plebeo napoletano e il dramma della miseria ………………………... 37 1.1.1- La miseria e la povertà …………………………………………………… 55 1.1.2- Il fatalismo e il riscatto ………………………………………………… 116 1.1.3- Napoli prima e dopo la guerra …………………………………………… 161 1.2- L’emigrazione 1.2.1- Accenni storici …………………………………………………………… 180 1.2.2- Il grande esodo nella letteratura italiana …………………………………. 191 1.2.3- L’emigrazione nei libri di Rea ………………………………………….. 213 1.3- Le strutture sociali ……………………………………………………………….. 230 CAPITOLO SECONDO:TECNICA NARRATIVA 2.1- Uso linguistico particolare Rea dal «notevolissimo» dono verbale alla maturità linguistica ………… 271 2.2- Il personaggio di Rea, «dalla mimesi alla coscienza» ………………………. 370 2.3- L’autobiografismo …………………………………………………………… 422 CONCLUSIONE …………………………………………………………… 458 BIBLIOGRAFIA ………………………………………………………………… 471 - 2 - - 3 - INTRODUZIONE REA TRA MERIDIONALISMO E NEOREALISMO - 4 - Ho sempre pensato di non essere stato destinato a scrivere cose grandi; e scontento di tutto quanto ho scritto da non avere la forza di rileggerlo; ho creduto nell’ispirazione, che esiste, ma che viene raramente. -

Fondo De Robertis

Archivio Contemporaneo “Alessandro Bonsanti” Gabinetto G.P. Vieusseux Fondo Giuseppe De Robertis inventario dei manoscritti a cura di Maria Cristina Chiesi Firenze, 2000 Fondo Giuseppe De Robertis. Inventario dei manoscritti Tra le sue carte Giuseppe De Robertis ha conservato un considerevole numero di Manoscritti, oltre a quelli in taluni casi allegati alle lettere ricevute e archiviate insieme con quelle: i suoi, non tutti comunque numerosissimi, e alcuni di altri autori. Essi costituiscono due serie nel Fondo, contraddistinte rispettivamente dai numeri 2 e 3, che fanno seguito alla serie 1 che individua la Corrispondenza. Esiste poi una quarta serie che raccoglie i ri- tagli di giornale. I manoscritti di De Robertis si riferiscono alla sua molteplice attività di critico, attento ai classici e parallelamente ai contemporanei, e tramandano saggi raccolti in volume, articoli pubblicati in pe- riodici, appunti preparatori degli uni e degli altri, lezioni universitarie, conferenze. Sono stati rior- dinati e catalogati attuando una suddivisione per autore trattato, ognuno dei quali viene a costituire un fascicolo contraddistinto da un numero, che nella segnatura occupa il secondo posto (es. D. R. 2. 16 indica il fascicolo Bilenchi). Nel primo fascicolo sono stati collocati gli scritti di argomento miscellaneo, che nella segnatura recano il numero 1, poi di seguito tutti gli altri in ordine alfabeti- co secondo il nome dell'autore su cui verte lo scritto. Infine i non identificati. All'interno di ogni argomento, nel rispetto della sequenza cronologica, a ciascuna unità archivistica catalogata analiti- camente, ossia a ogni scritto, è stato assegnato un numero collocato nella segnatura in terza posi- zione (es. -

Other Worlds: Travel Literature in Italy

Spring 2019 - Other Worlds. Travel Literature in Italy ITAL-UA 9283 Wednesdays, 10:30-1:15 pm Classroom Location TBA Class Description: This course, taught in English, will focus on the representation of travel experience in Modern Italian Literature and its related media, especially 20th Century Cinema, Modernist and Futurist Art, underground comics, and the way they intersect with each other. Its aim is to offer the student a new pattern in the succession of tendencies, movements and mass cultures, with a broader perspective, spanning from the 19th Century Post-Unification Italian culture and literature (Manzoni) to the 1980s “cult” writers and cartoonists and literary groups from the 1990s and 2000s (Tondelli, Ammanniti, Pazienza). With this pattern the student will be introduced to the dynamics of journey in the Italian culture and literature: not only a spatial journey abroad (in America with Calvino, The Orient with Tabucchi, Africa with Pasolini and Celati) or inland (especially the South of Carlo Levi), but also intellectually, politically and spiritually speaking: a path between the Wars (with Malaparte and Levi), the economic Boom, the Generation of ’68 and ’77, a psychedelic trip in New Age trends, and the so called Pulp Generation or Young Cannibals. To foster the student’s feedback one Site-visit will be proposed (at the Fondazione Casamonti in Florence) and a special Field Trip will be scheduled in Milan, to visit the new “Book Pride” Book Fair and interview a contemporary Italian writer and/or translator and/or editor at Verso Bookshop. With these topics and authors, the student will be engaged in a different history of Italian literature and culture, using also her or his knowledge in the Florentine context.