SRF Persian Literary Theory (Aligarh, August 2009)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Illumination of the Essence of the Concepts of Spirit

NOVATEUR PUBLICATIONS JournalNX- A Multidisciplinary Peer Reviewed Journal ISSN No: 2581 - 4230 VOLUME 7, ISSUE 6, June. -2021 ILLUMINATION OF THE ESSENCE OF THE CONCEPTS OF SPIRIT AND BODY IN THE RUBAIYATS OF OMAR KHAYYAM Yunusova Gulnoza Akramovna A Teacher of English Language Department Bukhara State Medical Institute ABSTRACT: INTRODUCTION: The Rubaiyat is a collection of four If we be two, we two are so line stanzas. Originally, it was written by As stiff twin-compasses are two; Omar Khayyam, a Persian poet, but later it Thy Soul, the fixt foot, makes no show was translated by Edward FitzGerald into To move, but does if the other do. English. It is translated version of The Rubaiyat actually is a stanza form FitzGerald, established in five editions that equal to a quatrain but the term is still known make the Rubaiyat widely known in the in the local use. He reflects on the frailty of world of literature, especially English human existence, the cruelty of fate and literature. This study deals with the 1859 ignorance of man. All of his ideas belong to the first edition. The Rubaiyat is the exposition concept of contemplation in Sufism, and these of Khayyam's contemplation of life and become one of the contributions to the world of Divinity, which is highly appreciated, and of literature. Therefore, it is proper for Khayyam's great importance in the world of literature Rubaiyat to be remembered by means of and a stepping progress to spirituality. analysis. Finally, it is hoped that this analysis Concerning the contemplation of Divine gives a gleam of sufi teaching. -

Michael Craig Hillmann–Résumé Copy

Michael Craig Hillmann–Résumé, 1996-2017 3404 Perry Lane, Austin, Texas 78731, USA 512-451-4385 (home tel), 512-653-5152 (cell phone) UT Austin WMB 5.146 office: 512-475-6606 (tel) and 512-471-4197 (fax) [email protected] and [email protected] (e-mail addresses) Web sites: www.utexas.Academia.edu/MichaelHillmann, www.Issuu.com/MichaelHillmann Academic Training_____________________________________________________________________________________________ • Classics, College of the Holy Cross, Worcester (MA), 1958-59. • B.A., English literature, Loyola University Maryland, Baltimore, MD), 1962. • Postgraduate study, English literature, The Creighton University, Omaha (NB), 1962-64. • M.A., Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations, The University of Chicago, 1969. • Postgraduate study, Persian literature, University of Tehran, 1969-73. • Ph.D., Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations, The University of Chicago, 1974. • M.A., English Literature, Texas State University at San Marcos (1997). Professional Positions since 1996__________________________________________________________________________________ • Professor of Persian, The University of Texas at Austin, 1974- . • President, Persepolis Institute (non-academic Persian Language consultants), Austin, 1977- . Teaching since 1996____________________________________________________________________________________________ Language • Elementary Colloquial/Spoken and Bookish/Written Persian (First-year Persian 1 and 2) • Elementary Persian Reading for Iranian Heritage Speakers • Intermediate -

The Implications of the Iranian Reform Movement's Islamization Of

The Implications of the Iranian Reform Movement’s Islamization of Secularism for a Post-Authoritarian Middle East by James Matthew Glassman An honors thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts with honors designation in International Affairs Examining Committee: Dr. Jessica Martin, Primary Thesis Advisor International Affairs Dr. John Willis, Secondary Thesis Advisor History Dr. Vicki Hunter, Honors Committee Advisor International Affairs UNIVERSITY OF COLORADO AT BOULDER DEFENDED APRIL 3, 2014 For over the soul God can and will let no one rule but Himself. Therefore, where temporal power presumes to proscribe laws for the soul, it encroaches upon God’s government and only misleads and destroys souls. ~ خداوند منی تواند و اجازه خنواهد داد که هیچ کس به غری از خودش بر روح انسان تسلط داش ته ابشد. در نتیجه هر جایی که قدرت دنیوی سعی کند قواننی روحاین را مقرر کند، این مس ئهل یک جتاوز به حکومت الهیی می ابشد که فقط موجب گمراهی و ویراین روح می شود. ~ Martin Luther 1523 AD - i - To my parents, Rick and Nancy, and my grandfather, Edward Olivari. Without your love and support, none of this would have been possible. and To Dr. J. Thank you for believing in me and for giving me a second chance at the opportunity of a lifetime. - ii - Table of Contents Glossary of Essential Terms in Persian ...................................................................................... iv A Note on the Transliteration ..................................................................................................... vi Abstract ...................................................................................................................................... vii Introduction: The Emergence of a Secular and Islamic Democratic Discourse in Iran ........ 1 Chapter One – Historical Framework Part One: Post-Colonial Secular and Islamic Thought in Iran 1953 - 1989 ........................................................................................................ -

Federal Magistrates Court of Australia

FEDERAL MAGISTRATES COURT OF AUSTRALIA MZXMM v MINISTER FOR IMMIGRATION & ANOR [2007] FMCA 975 MIGRATION – Protection visa – irrelevant consideration – reference to Armeniapedia/Wikipedia web site – whether jurisdictional error – social group – apostates – whether failure to consider claim – application allowed. Migration Act 1958 , ss.420, 422B, 424A, 425 W68/01A v Minister for Immigration & Multicultural Affairs [2002] FCA 148 Abebe v Commonwealth (1999) 197 CLR 510 NAVK v MIMIA [2005] FCAFC 124 Minister for Immigration & Multicultural Affairs; Ex parte Applicant S20/2002 (2003) 77 ALJR 1165 SZCIJ v MIMIA [2006] FCAFC 62 MIMIA v Lay Lat [2006] FCAFC 61 SZBEL v MIMIA [2006] HCA 63 Applicant: MZXMM First Respondent: MINISTER FOR IMMIGRATION & CITIZENSHIP Second Respondent: MIGRATION REVIEW TRIBUNAL File number: MLG1232 of 2006 Judgment of: McInnis FM Hearing date: 6 March 2007 Date of last submission: 3 April 2007 Delivered at: Melbourne Delivered on: 13 June 2007 MZXMM v Minister for Immigration & Anor [2007] FMCA 975 Cover sheet and Orders: Page 1 REPRESENTATION Counsel for the Applicant: Ms N Karapanagiotidis Solicitors for the Applicant: Asylum Seeker Resource Centre Counsel for the First Mr P Gray Respondent: Solicitors for the First DLA Phillips Fox Respondent: ORDERS (1) A writ of certiorari issue directed to the Second Respondent, quashing the decision of the Second Respondent dated 29 August 2006. (2) A writ of mandamus issue directed to the Second Respondent, requiring the Second Respondent to determine according to law the application for review. (3) The First Respondent shall pay the Applicant’s costs. MZXMM v Minister for Immigration & Anor [2007] FMCA 975 Cover sheet and Orders: Page 2 FEDERAL MAGISTRATES COURT OF AUSTRALIA AT MELBOURNE MLG1232 of 2006 MZXMM Applicant And MINISTER FOR IMMIGRATION & CITIZENSHIP First Respondent REFUGEE REVIEW TRIBUNAL Second Respondent REASONS FOR JUDGMENT 1. -

Naqshbandi Sufi, Persian Poet

ABD AL-RAHMAN JAMI: “NAQSHBANDI SUFI, PERSIAN POET A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for The Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Farah Fatima Golparvaran Shadchehr, M.A. The Ohio State University 2008 Approved by Professor Stephen Dale, Advisor Professor Dick Davis Professor Joseph Zeidan ____________________ Advisor Graduate Program in History Copyright by Farah Shadchehr 2008 ABSTRACT The era of the Timurids, the dynasty that ruled Transoxiana, Iran, and Afghanistan from 1370 to 1506 had a profound cultural and artistic impact on the history of Central Asia, the Ottoman Empire, and Mughal India in the early modern era. While Timurid fine art such as miniature painting has been extensively studied, the literary production of the era has not been fully explored. Abd al-Rahman Jami (817/1414- 898/1492), the most renowned poet of the Timurids, is among those Timurid poets who have not been methodically studied in Iran and the West. Although, Jami was recognized by his contemporaries as a major authority in several disciplines, such as science, philosophy, astronomy, music, art, and most important of all poetry, he has yet not been entirely acknowledged in the post Timurid era. This dissertation highlights the significant contribution of Jami, the great poet and Sufi thinker of the fifteenth century, who is regarded as the last great classical poet of Persian literature. It discusses his influence on Persian literature, his central role in the Naqshbandi Order, and his input in clarifying Ibn Arabi's thought. Jami spent most of his life in Herat, the main center for artistic ability and aptitude in the fifteenth century; the city where Jami grew up, studied, flourished and produced a variety of prose and poetry. -

The Textual History of the Qur'an

The Textual History of the Qur’an by Dr Bernie Power ccording to most Muslims, the Qur’an has existed forever. It is called the ‘mother of the book’ (Q.3:7; 13:39; A1 43:4) and ‘the preserved tablet’ (Q.85:21,22) which has always been present beside the throne of Allah. In Muslim understanding, it was revealed or ‘sent down’ piece by piece to the prophet Muhammad (b.570 CE) via the angel Gabriel during 23 years from 610 CE until his death in 632 CE. Muhammad then recited what he heard (since he was illiterate - Q.7:158) to his followers who wrote them down or memorized his sayings. He spoke in the language of the Quraish, one of the current Arabic dialects. At a later stage Muhammad’s revelations were all gathered into one book. 20 years later this was edited into a single authorized copy, and that is said to be identical with the present Arabic Qur’an. Muslims are so confident about this process that they make statements like the following: “So well has it been preserved, both in memory and in writing, that the Arabic text we have today is identical to the text as it was revealed to the Prophet. Not even a single letter has yielded to corruption during the passage of the centuries.”2 Another publication, widely distributed in Australia, says: “No other book in the world can match the Qur’an ... The astonishing fact about this book of ALLAH is that it has remained unchanged, even to a dot, over the last fourteen hundred years. -

Jesus and Muhammed in the Qur'an: a Comparison and Contrast

Jesus and Muhammed in the Qur’an: A Comparison and Contrast Norman L. Geisler Norman L. Geisler is President and Islam is the second largest and the fastest those nearest to God; He shall speak to the people in childhood and in Professor of Theology and Apologetics growing religion in the world. One out of maturity. And he shall be (of the at Southern Evangelical Seminary in every five persons on earth is a Muslim— company) of the righteous.” She Charlotte, North Carolina. He is the some 1.2 billion. As such, it presents one said: “O my Lord! How shall I have a son when no man hath touched author or co-author of some fifty books of the greatest challenges to Christianity me?” He said: “Even so: God and numerous articles and has spoken in the world today. It behooves us, then, createth what He willeth: When He frequently across the country and in to understand it better. And there is no hath decreed a plan, He but saith to it, ‘Be,’ and it is! And God will teach twenty-five countries. Dr. Geisler is the better way to understand Islam than him the Book and Wisdom, the Law co-author (with Abdul Saleeb) of through its own Holy Book, the Qur’an. and the Gospel, and (appoint him) an apostle to the Children of Israel, Answering Islam: The Crescent in Light We will begin with a comparison of Jesus (with this message): ‘“I have come of the Cross (Baker, 2002). and Muhammed in the Qur’an. to you, with a Sign from your Lord, in that I make for you out of clay, as it were, the figure of a bird, and A Brief Comparison of Jesus and breathe into it, and it becomes a bird Muhammed in the Qur’an by God’s leave: And I heal those born blind, and the lepers, and I Jesus in the Qur’an Muhammed in the Qur’an Virgin Born Not Virgin Born quicken the dead, by God’s leave; Sinless Sinful and I declare to you what ye eat, and Called “Messiah” Not called “Messiah” what ye store in your houses. -

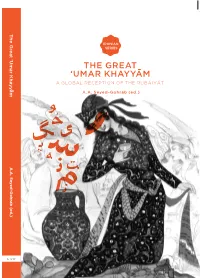

The Great 'Umar Khayyam

The Great ‘Umar Khayyam Great The IRANIAN IRANIAN SERIES SERIES The Rubáiyát by the Persian poet ‘Umar Khayyam (1048-1131) have been used in contemporary Iran as resistance literature, symbolizing the THE GREAT secularist voice in cultural debates. While Islamic fundamentalists criticize ‘UMAR KHAYYAM Khayyam as an atheist and materialist philosopher who questions God’s creation and the promise of reward or punishment in the hereafter, some A GLOBAL RECEPTION OF THE RUBÁIYÁT secularist intellectuals regard him as an example of a scientist who scrutinizes the mysteries of the universe. Others see him as a spiritual A.A. Seyed-Gohrab (ed.) master, a Sufi, who guides people to the truth. This remarkable volume collects eighteen essays on the history of the reception of ‘Umar Khayyam in various literary traditions, exploring how his philosophy of doubt, carpe diem, hedonism, and in vino veritas has inspired generations of poets, novelists, painters, musicians, calligraphers and filmmakers. ‘This is a volume which anybody interested in the field of Persian Studies, or in a study of ‘Umar Khayyam and also Edward Fitzgerald, will welcome with much satisfaction!’ Christine Van Ruymbeke, University of Cambridge Ali-Asghar Seyed-Gohrab is Associate Professor of Persian Literature and Culture at Leiden University. A.A. Seyed-Gohrab (ed.) A.A. Seyed-Gohrab WWW.LUP.NL 9 789087 281571 LEIDEN UNIVERSITY PRESS The Great <Umar Khayyæm Iranian Studies Series The Iranian Studies Series publishes high-quality scholarship on various aspects of Iranian civilisation, covering both contemporary and classical cultures of the Persian cultural area. The contemporary Persian-speaking area includes Iran, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, and Central Asia, while classi- cal societies using Persian as a literary and cultural language were located in Anatolia, Caucasus, Central Asia and the Indo-Pakistani subcontinent. -

A Political Analysis of Folktales of Iran Yass Alizadeh University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected]

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 12-9-2014 Tales that Tell All: A Political Analysis of Folktales of Iran Yass Alizadeh University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Alizadeh, Yass, "Tales that Tell All: A Political Analysis of Folktales of Iran" (2014). Doctoral Dissertations. 610. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/610 Tales that Tell All: A Political Analysis of Folktales of Iran Yass Alizadeh, PhD University of Connecticut 2014 Abstract This research presents an analytical study of the rewritten folktales of Iran in 20th century, and investigates the ideological omissions and revisions of oral tales as textual productions in modern Iran. Focusing on the problematic role of folktales as tales about the unreal and the fantastic serving a political purpose, this study traces the creative exercises of Iranian storytellers who apply ideological codes and meanings to popular folk language. The works of Mirzadeh Eshqi (1893-1924), Sadegh Hedayat (1903-1951), Samad Behrangi (1939-1968) and Bijan Mofid (1935-1984) are examples of a larger collection of creative writing in Iran that through the agency of folklore shape the political imagination of Iranian readers. While Eshqi’s revolutionary ideas are artistically imbedded in oral culture of the Constitution era, Hedayat’s fiction follows with an intricate fusion of folklore and tradition. Later in the 20th Century, Behrangi introduces politically charged children’s tales to an invested audience, and Mofid dramatizes the joys and sorrow of Iranian culture through a familiar fable. -

Southern California Bible College & Seminary

Southern California Seminary Community Course: Understanding Islam SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA SEMINARY 2075 EAST MADISON AVENUE • EL CAJON • CALIFORNIA 92019–1108 COMMUNITY COURSE: UNDERSTANDING ISLAM (NOT FOR CREDIT) May 9 – June 20, 2017 Tuesdays, 6:00- 9:00 p.m. Professor: Sohrab Ramtin, ThM, DMin (cand) Email: [email protected] Office: 619-583-8295 The Lord’s Prayer in Farsi The Muslim Creed in Arabic COURSE DESCRIPTION This course is offered for personal enrichment to members of the community who wish to audit a seminary course. It is designed as an in depth study and examination of Islam. Time will be given to the history and culture of Islam with the goal of preparing students to share their faith and develop a ministry to reach out to the Muslims with the Gospel. Topics covered will include the life of Mohammed, the history, growth and culture of Islam, along with the doctrines of its major sects. A portion of the course will be devoted to a brief look at the Qur’an and Qur’anic literature. The main focus will be on the theology of Islam and its worldview. ABOUT YOUR PROFESSOR Sohrab Ramtin was born into a Muslim family in Tehran, Iran. He came to faith in Christ in 1981 after coming to the U.S. He studied math and physics before going on to earn his MDiv from Trinity Evangelical Divinity School, and afterward his ThM and DMin from Southern California Seminary. Today he serves as program producer for a Christian TV and radio network to Iran and Afghanistan and teaches courses in Islamic studies and world religions. -

Imagining Iran: Contending Political Discourses in Modern Iran

IMAGINING IRAN: CONTENDING POLITICAL DISCOURSES IN MODERN IRAN By MAJID SHARIFI A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2008 1 © Majid Sharifi 2 “To Sheki, Annahitta, and Ava with Love” 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am very grateful and deeply indebted to many people whose assistance made this project possible. First and foremost, I thank my wife, Sheki, whose patience and support were indispensable. I also thank my two daughters, Annahitta and Ava, for the sacrifices each made on my behalf. Two years of research have gone into this dissertation, which would not have been possible without the indispensable influence, guidance, direction, and inspiration of the people in the Department of Political Science at the University of Florida. I must thank Professor Goran Hyden, who influenced my decision in starting the Ph.D. program in 2003. Without Professor Hyden, I probably would have stayed in Miami. I am most indebted to Professor Ido Oren, who stimulated my initial interest in the politics of identity, interpretative epistemology, and the significance of history. During the past two years, Dr. Oren has spent numerous hours listening, reading, and constructively criticizing my work. Without Professor Oren, my approach would have been less bold and more conventional. Professor Oren taught me innovative ways of looking at history, politics, and identities. Most significantly, I am grateful to Professor Leann Brown who has been the guidepost for directing this research. Whenever I was in need of guidance or inspiration, her office was my first and only destination. -

{PDF EPUB} ???? ? ?? ??? ?? ??? by Ali Dashti

by Ali Dashti ﺑﯿﺴﺖ و ﺳﮫ ﺳﺎل ٢٣ ﺳﺎل {Read Ebook {PDF EPUB Gomac. .ﺑﯿﺴﺖ و ﺳﮫ ﺳﺎل ﮐﺘﺎﺑﯽ اﺳﺖ درﺑﺎرهٔ زﻧﺪﮔﯽ ﷴ ﭘﯿﺎﻣﺒﺮ اﺳﻼم ﻧﻮﺷﺘﮫٔ ﻋﻠﯽ .Years – Bisto Se Sal [ali dashti] on *FREE* shipping on qualifying offers 23 Twenty Three Years – Ali Dashti. by Ali Dasti. Topics Muhammad Mohammad Ali Dasti. Collection opensource. Language English. Prophetic. , English, Book edition: Twenty three years: a study of the prophetic career of Mohammad / by ‘Ali Dashti ; translated from the Persian by F.R.C. Bagley. Author: Kagataur Vok Country: Guatemala Language: English (Spanish) Genre: Career Published (Last): 10 November 2016 Pages: 422 PDF File Size: 20.83 Mb ePub File Size: 13.22 Mb ISBN: 452-9-94637-749-8 Downloads: 9932 Price: Free* [ *Free Regsitration Required ] Uploader: Daizragore. One of his harsher critics, Ehsan Tabariwrote:. Ali Dashti. He studied Islamic theology, history, Arabic and Persian grammar, and classical literature in madrasas in Karbala and Najaf both in Iraq. Are their any refutations to his works? To include a comma in your tag, surround the tag with double quotes. Language English View all editions Prev Next edition 3 of 4. Dar Qalamrow-e Sa’di, on the poet and prose-writer Sa’di ? Leader of the Justice Party — He was connected to the monarchial regime I believe he was a senator in the puppet parliament for 20 or so yearssupposedly went to the Hawzah in his young age and wrote anti-islamic books after the Revolution. Ali Dashti – Theology and General Religion – Nooh rated it did not like it Mar 19, I’d like to read this book on Kindle Don’t have a Kindle? English Choose a language for shopping.