Zheng He Documents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

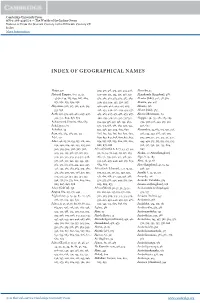

Index of Geographical Names

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-42465-3 — The Worlds of the Indian Ocean Volume 2: From the Seventh Century to the Fifteenth Century CE Index More Information INDEX OF GEOGRAPHICAL NAMES Abaya, 571 309, 317, 318, 319, 320, 323, 328, Akumbu, 54 Abbasid Empire, 6–7, 12, 17, 329–370, 371, 374, 375, 376, 377, Alamkonda (kingdom), 488 45–70, 149, 185, 639, 667, 669, 379, 380, 382, 383, 384, 385, 389, Alaotra (lake), 401, 411, 582 671, 672, 673, 674, 676 390, 393, 394, 395, 396, 397, Alasora, 414, 427 Abyssinia, 306, 317, 322, 490, 519, 400, 401, 402, 409, 415, 425, Albania, 516 533, 656 426, 434, 440, 441, 449, 454, 457, Albert (lake), 365 Aceh, 198, 374, 425, 460, 497, 498, 463, 465, 467, 471, 478, 479, 487, Alborz Mountains, 69 503, 574, 609, 678, 679 490, 493, 519, 521, 534, 535–552, Aleppo, 149, 175, 281, 285, 293, Achaemenid Empire, 660, 665 554, 555, 556, 557, 558, 559, 569, 294, 307, 326, 443, 519, 522, Achalapura, 80 570, 575, 586, 588, 589, 590, 591, 528, 607 Achsiket, 49 592, 596, 597, 599, 603, 607, Alexandria, 53, 162, 175, 197, 208, Acre, 163, 284, 285, 311, 312 608, 611, 612, 615, 617, 620, 629, 216, 234, 247, 286, 298, 301, Adal, 451 630, 637, 647, 648, 649, 652, 653, 307, 309, 311, 312, 313, 315, 322, Aden, 46, 65, 70, 133, 157, 216, 220, 654, 657, 658, 659, 660, 661, 662, 443, 450, 515, 517, 519, 523, 525, 230, 240, 284, 291, 293, 295, 301, 668, 678, 688 526, 527, 530, 532, 533, 604, 302, 303, 304, 306, 307, 308, Africa (North), 6, 8, 17, 43, 47, 49, 607 309, 313, 315, 316, 317, 318, 319, 50, 52, 54, 70, 149, 151, 158, -

Zheng He and the Confucius Institute

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations Office of aduateGr Studies 3-2018 The Admiral's Carrot and Stick: Zheng He and the Confucius Institute Peter Weisser Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd Part of the Asian Studies Commons Recommended Citation Weisser, Peter, "The Admiral's Carrot and Stick: Zheng He and the Confucius Institute" (2018). Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations. 625. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd/625 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Office of aduateGr Studies at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ADMIRAL’S CARROT AND STICK: ZHENG HE AND THE CONFUCIUS INSTITIUTE A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Social Science by Peter Eli Weisser March 2018 THE ADMIRAL’S CARROT AND STICK: ZHENG HE AND THE CONFUCIUS INSTITIUTE A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by Peter Eli Weisser March 2018 Approved by: Jeremy Murray, Committee Chair, History Jose Munoz, Committee Member ©2018 Peter Eli Weisser ABSTRACT As the People’s Republic of China begins to accumulate influence on the international stage through strategic usage of soft power, the history and application of soft power throughout the history of China will be important to future scholars of the politics of Beijing. -

Historical Romance and Sixteenth-Century Chinese Cultural Fantasies

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2013 Genre and Empire: Historical Romance and Sixteenth-Century Chinese Cultural Fantasies Yuanfei Wang University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, and the History Commons Recommended Citation Wang, Yuanfei, "Genre and Empire: Historical Romance and Sixteenth-Century Chinese Cultural Fantasies" (2013). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 938. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/938 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/938 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Genre and Empire: Historical Romance and Sixteenth-Century Chinese Cultural Fantasies Abstract Chinese historical romance blossomed and matured in the sixteenth century when the Ming empire was increasingly vulnerable at its borders and its people increasingly curious about exotic cultures. The project analyzes three types of historical romances, i.e., military romances Romance of Northern Song and Romance of the Yang Family Generals on northern Song's campaigns with the Khitans, magic-travel romance Journey to the West about Tang monk Xuanzang's pilgrimage to India, and a hybrid romance Eunuch Sanbao's Voyages on the Indian Ocean relating to Zheng He's maritime journeys and Japanese piracy. The project focuses on the trope of exogamous desire of foreign princesses and undomestic women to marry Chinese and social elite men, and the trope of cannibalism to discuss how the expansionist and fluid imagined community created by the fiction shared between the narrator and the reader convey sentiments of proto-nationalism, imperialism, and pleasure. -

Zhao Rugua'nın Zhufanzhi Adlı Eserine Göre XII-XIII. Yüzyılda Orta

T.C. ANKARA ÜNİVERSİTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ TARİH (ORTAÇAĞ TARİHİ) ANABİLİM DALI Zhao Rugua’nın Zhufanzhi Adlı Eserine Göre XII-XIII. Yüzyılda Orta Doğu Kentleri ve Ticari Emtia Yüksek Lisans Tezi Shan-Ju LIN Ankara-2015 T.C. ANKARA ÜNİVERSİTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ TARİH (ORTAÇAĞ TARİHİ) ANABİLİM DALI Zhao Rugua’nın Zhufan Zhi Adlı Eserine Göre XII-XIII. Yüzyılda Orta Doğu Kentleri ve Ticari Emtia Yüksek Lisans Tezi Shan-Ju LIN Tez Danışmanı Doç. Dr. Hatice ORUÇ Ankara-2015 T.C. ANKARA ÜNİVERSİTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ TARİH (ORTAÇAĞ TARİHİ) ANABİLİM DALI Zhao Rugua'nın Zhufanzhi Adlı Eserine Göre 12-13. Yüzyılda Ortadoğu Kentleri Ve Ticari Emtia Yüksek Lisans Tezi Tez Danışmanı: 0 u ç Tez Jürisi Üyeleri Adı ve Soyadı İmzası L Ç Tez Sınavı Tarihi .?K.J.?£.L2P... TÜRKİYE CUMHURİYETİ ANKARA ÜNİVERSİTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ MÜDÜRLÜĞÜNE Bu belge ile, bu tezdeki bütün bilgilerin akademik kurallara etik davranış ilkelerine uygun olarak toplanıp sunulduğunu beyan ederim. Bu kural ve ilkelerin gereği olarak, çalışmada bana ait olmayan tüm veri, düşünce ve sonuçları andığımı ve kaynağını gösterdiğimi ayrıca beyan ederim. (....../....../200...) Tezi Hazırlayan Öğrencinin Adı ve Soyadı .................................................... İmzası .................................................... ĠÇĠNDEKĠLER ÖNSÖZ ........................................................................................................................ 4 GĠRĠġ .......................................................................................................................... -

Intra-Asian Trade and the World Market

Latham-FM.qxd 8/12/05 7:22 AM Page i Intra-Asian Trade and the World Market Intra-Asian trade is a major theme of recent writing on Asian economic history. From the second half of the nineteenth century, intra-Asian trade flows linked Asia into an integrated economic system, with reciprocal benefits for all participants. But although this was a network from which all gained, there was also considerable inter-Asian competition between Asian producers for these Asian markets and those of the wider world. This collection presents captivating ‘snap-shots’ of trade in specific commodities, alongside chapters comprehensively covering the region. The book covers China’s relative backwardness, Japanese copper exports, Japan’s fur trade, Siam’s luxury rice trade, Korea, Japanese shipbuilding, the silk trade, the refined sugar trade, competition in the rice trade, the Japanese cotton textile trade to Africa, multilateral settlements in Asia, the cotton textile trade to Britain and the growth of the palm oil industry in Malaysia and Indonesia. The opening of Asia, especially Japan and China, liberated the creative forces of the market within the new interactive Asian economy. This fascinating book fills a particular gap in the literature on intra-Asian trade from the sixteenth century to the present day. It will be of particular interest to historians and economists focusing on Asia. A.J.H. Latham retired as Senior Lecturer in International Economic History at the University of Wales, Swansea, in 2003. His recent books include Rice: The Primary Commodity. He co-edited (with Kawakatsu) Asia Pacific Dynamism, 1550–2000 (both are published by Routledge). -

MUSLIMS in AUSTRALIA: a Brief History (Excerpts) by Bilal Cleland

MUSLIMS IN AUSTRALIA: A Brief History (Excerpts) by Bilal Cleland From: http://www.icv.org.au/history4.shtml The Islamic Council of Victoria website ISLAM IN OUR NEAR NORTH Many Australians are accustomed to thinking of the continent as being isolated for thousands of years, cut-off from the great currents flowing throughout world civilisation. A sense of this separation from 'out there' is given in "The Tyranny of Distance" by Blainey who writes "In the eighteenth century the world was becoming one world but Australia was still a world of its own. It was untouched by Europe's customs and commerce. It was more isolated than the Himalayas or the heart of Siberia." [1] The cast of mind which is reflected in this statement, from one of Australia's most distinguished modern historians, understands 'the world' and 'Europe's customs and commerce' as somehow inextricably linked. Manning Clark writes of isolation, the absence of civilisation, until the last quarter of the eighteenth century, attributing this partly to "the internal history of those Hindu, Chinese and Muslim civilisations which colonized and traded in the archipelago of southeast Asia." [2] While not linking Europe with civilisation, Australia still stands separate and alone. There is no doubt that just to our north, around southeast Asia and through the straits between the islands of the Indonesian archipelago, there was a great deal of coming and going by representatives of all world civilisations. Representatives of the Confucian, Hindu, Buddhist, Islamic and latterly, Western Christian civilisations, visited, struck root and occasionally, evolved into something else. -

From Tin to Pewter: Craft and Statecraft in China, 1700-1844

From Tin to Pewter: Craft and Statecraft in China, 1700-1844 Yijun Wang Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2019 © 2019 Yijun Wang All rights reserved ABSTRACT From Tin to Pewter: Craft and Statecraft in China, 1700 to 1844 Yijun Wang This dissertation examines the transmissions of technology and changes in the culture of statecraft by tracing the itinerary of tin from ore in mines to everyday objects. From the eighteenth century, with the expansion of the Qing empire and global trade, miners migrated from the east coast of China to the southwest frontiers of the Qing empire (1644-1912) and into Southeast Asia, bringing their mining technology with them. The tin from Southeast Asia, in return, inspired Chinese pewter artisans to invent new styles and techniques of metalworking. Furthermore, the knowledge of mining, metalworking, and trade was transferred from miners, artisans, and merchants into the knowledge system of scholar-officials, gradually changing the culture of statecraft in the Qing dynasty. This dissertation explores how imperial expansion and the intensive material exchange brought by global trade affected knowledge production and transmission, gradually changing the culture of statecraft in China. In the Qing dynasty, people used tin, the component of two common alloys, pewter and bronze, to produce objects of daily use as well as copper coins. Thus, tin was not only important to people’s everyday lives, but also to the policy-making of the Qing state. In this way, tin offers an exceptional opportunity to investigate artisans and intellectuals’ approach to technology, while it also provides a vantage point from which to examine how Qing bureaucrats managed the world, a world of human and non-human resources. -

African Diaspora in China: Reality, Research and Reflection

African Diaspora in China: Reality, Research and Reflection by Li Anshan, Ph.D. [email protected] Center for African Studies, School of International Studies, Peking University, Beijing, China Abstract The history of human beings is a history of (im)migration. From the ancient times, people moved from one place to the other to find better environments for survival or development. After the modern international system came into being with borders being a necessity of the nation-state, immigration became an issue, be it from national policy or international concerns. With the recent development of China-Africa relations, a wave of bilateral migration occurred.1 This phenomenon created an enthusiasm for the study of migration between China and Africa. There are studies on Chinese either on the African continent (Li, 2000, 2006, 2012a), on particular regions (Ly Tio Fane-Pines, 1981, 1985), or on different countries (Human 1984; Yap & Leong, 1996; Wong-Hee-kan, 1996; Ly-Tio-Fane Pineo & Lim Fat, 2008; Park, 2008), yet the African diaspora in China is much less studied. As Bodomo correctly points out “Africans did not just start moving into China in the 21st century”, “This history must be placed in the context of the wider African presence in Asia, which itself has not yet been the subject of sustained research” (Bodomo, 2012). This article constitutes a historiography of the African presence in China; it is aimed at getting a clearer understanding of the connections between reality and research, and if possible, provide some indication for future study. It is divided into four parts, African people in early China, the issue of Kunlun, the origin and jobs of African people in ancient China, and the study of African people in contemporary China. -

6 Bibliography 10/9/02 1:31 Pm Page 477

6 Bibliography 10/9/02 1:31 pm Page 477 1 2 3 SELECT 4 5 BIBLIOGRAPHY 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 477 6 Bibliography 10/9/02 1:31 pm Page 478 BIBLIOGRAPHY 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 478 6 Bibliography 10/9/02 1:31 pm Page 479 SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY Chapters 1: The Emperor’s Grand Plan and 2: A Thunderbolt Strikes 1 2 Abru, Hafiz (trs. K.M. Maitra), A Persian Embassy to China. Lahore, 1934. 3 Battuta, Ibn (trs. S. Lee), The Travels of Ibn Battuta. 1829. Bonavia, J., Collins Illustrated Guide to The Silk Road. The Guide Book Co. Ltd, Hong 4 Kong, 1988. 5 Boulnois, L. (trs. D. Chamberlin), The Silk Road. Allen & Unwin, 1966. Braudel, F. (trs. R. Mayne), A History of Civilizations. Penguin, 1994. 6 Chaudhuri, K.N., ‘A Note on Ibn Taghri Birdi’s description of Chinese Ships in Aden 7 and Jeddah’. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, no. 1, 1989, 112. 8 —— Trade and Civilisation in the Indian Ocean. Cambridge University Press, 1985. Dreyer, E.L., Early Ming China: A Political History 1355–1435. California, Stanford 9 University Press, 1982. 10 Dunn, R.E., The Adventures of Ibn Battuta a Muslim Traveller of the 14th Century. -

Mapping the Chinese and Islamic Worlds

Mapping the Chinese and Islamic Worlds Long before Vasco da Gama rounded the Cape of Good Hope en route to India, the peoples of Africa, the Middle East, and Asia engaged in vigorous cross-cultural exchanges across the Indian Ocean. This book focuses on the years 700 to 1500, a period when powerful dynasties governed both the Islamic and Chinese regions, to document the rela- tionship between the two worlds before the arrival of the Europeans. Through a close analysis of the maps, geographic accounts, and trav- elogues compiled by both Chinese and Islamic writers, the book traces the development of major contacts between people in China and the Islamic world and explores their interactions on matters as varied as diplomacy, commerce, mutual understanding, world geography, nav- igation, shipbuilding, and scientii c exploration. When the Mongols ruled both China and Iran in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, their geographic understanding of each other’s society increased mark- edly. This rich, engaging, and pioneering study offers glimpses into the worlds of Asian geographers and mapmakers, whose accumulated wis- dom underpinned the celebrated voyages of European explorers like Vasco da Gama. Hyunhee Park is an assistant professor of history at CUNY John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York City, where she teaches Chinese history, global history, and justice in the non-Western tradi- tion. She currently serves as an assistant editor of the academic journal Crossroads – Studies on the History of Exchange Relations in the East Asian World . Downloaded from Cambridge Books Online by IP 210.212.129.125 on Sun Dec 23 02:56:34 WET 2012. -

The Sino-African Higher Education and Cultural Exchange Before 1911: a Historical Review

Journal of Education and Practice www.iiste.org ISSN 2222-1735 (Paper) ISSN 2222-288X (Online) Vol.11, No.27, 2020 The Sino-African Higher Education and Cultural Exchange before 1911: A Historical Review Bouchaib Chkaif Department of education, Zhejiang University, Wensan Road 181, Hangzhou, China E-mail: [email protected] Abstract In the last few decades, much ink has been spilt on the Sino-African relations. However, most literature concentrated on the economic, diplomatic, and political aspects of the Sino-African encounter, while few pieces of research touched upon the educational and cultural aspects of this encounter. With the increasing higher education and cultural exchange between China and the African countries in recent years, looking back at history, as a source of valuable insights to understand the present and forecast the future of this relationship, comes to the fore. This paper intends, through an analogical approach, to review and unveil the Sino-African higher education and cultural exchange before 1911. The author argues that by reviewing the educational and cultural impact of both sides’ scholars’ and travellers’ visits with their backgrounds and legacies according to the modern literature on higher education exchange goals, these scholars’ and travellers’ visits would be regarded as the earliest forms of the Sino-African higher education and cultural exchange. Keywords: China, Africa, higher education exchange, cultural exchange, knowledge transfer DOI: 10.7176/JEP/11-27-01 Publication date: September 30th 2020 1. Introduction Modern literature places mutual cultural understanding and knowledge transfer among the core objectives of higher education generally and higher education exchange, particularly (Atalar, 2020; Marilyn DeLong et al., 2011; Sowa, 2002; Vande Berg, Paige, & Lou, 2012). -

Vol. 17/18 (2018) Crossroads Studies on the History of Exchange Relations in the East Asian World

Crossroads Studies on the History of Exchange Relations in the East Asian World OSTASIEN Verlag Vol. 17/18 (2018) Crossroads Studies on the History of Exchange Relations in the East Asian World 縱横 東亞世界交流史研究 クロスロード 東アジア世界の交流史研究 크로스로드 東아시아世界의交流史研究 Vol. 17/18 (2018) OSTASIEN Verlag All inscriptions from the Turfan region shown on the cover page can be found on the website “Xibu bianchui de qipa: Tulufan (Gaochang) muzhuan shufa” 西部边陲的奇葩—吐鲁番 (高昌) 墓砖书法 [www.sohu.com/a/237616750_100140832]. Black-and-White photos of these inscriptions are published in the monograph Tulufan chutu zhuanzhi jizhu 吐魯番出土磚誌集註, ed. by Hou Can 侯燦 and Wu Meilin 吳美琳. Chengdu: Bashu, 2004. [Top left:] Tang Kaiyuan 26 nian (738) Zhang Yungan ji qi mubiao 唐開元廿六年張運感及妻墓表 (p. 640, fig. 315); [left centre:] Gaochang Yanhe 11 nian (612) Zhang Zhongqing qi Jiaoshi mubiao 高昌延和十一年張 仲慶妻焦氏墓表 (p. 284, fig. 138); [bottom left:] Gaochang Yanchang 26 nian (586) zhongbing canjun Xinshi mubiao 高昌延昌廿六年中兵參軍辛氏墓表 (p. 176, fig. 81); [Top right:] Tang Yongchun 2 nian (683) Zhang Huan furen Qu Lian muzhiming 唐永淳二年張歡夫人麹連墓志 銘 (p. 575, fig. 292); [bottom right:] Gaochang Chongguang 1 nian (620) Zhang Azhi zi mubiao 高昌重光元年張阿質兒墓表 (p. 323, fig. 157). Editor in chief: Angela SCHOTTENHAMMER (Salzburg, Austria; McGill, Montreal, Canada; KU Leuven, Belgium) Co-Editors: Maddalena BARENGHI (Venezia, Italy) Alexander JOST (Salzburg, Austria) KOBAYASHI Fumihiko 小林史彦 (New York, USA) LI Jinxiu 李锦锈 (Beijing, China) LI Man 李漫 (Gent, Belgium) Achim MITTAG (Tübingen, Germany) Elke PAPELITZKY (Shanghai, China) PARK Hyunhee 박현희 朴賢熙 (New York, USA) Barbara SEYOCK (Bochum, Germany) This issue of Crossroads, dedicated to Chen Zhenxiu 陈朕秀 (1991–2019), has been edited with special assistance of Alexander Jost and Li Man.