Circuits of Identities in the Margins: Multicultural Encounters and Hybrid Biopolitics in Sinophone Texts Across Greater China and Southeast Asia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The South China Sea and Its Coral Reefs During the Ming and Qing Dynasties: Levels of Geographical Knowledge and Political Control Ulisesgrana Dos

East Asian History NUMBER 32/33 . DECEMBER 20061]uNE 2007 Institute of Advanced Studies The Australian National University Editor Benjamin Penny Associate Editor Lindy Shultz Editorial Board B0rge Bakken Geremie R. Barme John Clark Helen Dunstan Louise Edwards Mark Elvin Colin Jeffcott Li Tana Kam Louie Lewis Mayo Gavan McCormack David Marr Tessa Morris-Suzuki Kenneth Wells Design and Production Oanh Collins Printed by Goanna Print, Fyshwick, ACT This is a double issue of East Asian History, 32 and 33, printed in November 2008. It continues the series previously entitled Papers on Far Eastern History. This externally refereed journal is published twice per year. Contributions to The Editor, East Asian History Division of Pacific and Asian History Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Phone +61 2 6125 5098 Fax +61 2 6125 5525 Email [email protected] Subscription Enquiries to East Asian History, at the above address Website http://rspas.anu.edu.au/eah/ Annual Subscription Australia A$50 (including GST) Overseas US$45 (GST free) (for two issues) ISSN 1036-6008 � CONTENTS 1 The Moral Status of the Book: Huang Zongxi in the Private Libraries of Late Imperial China Dunca n M. Ca mpbell 25 Mujaku Dochu (1653-1744) and Seventeenth-Century Chinese Buddhist Scholarship John Jorgensen 57 Chinese Contexts, Korean Realities: The Politics of Literary Genre in Late Choson Korea (1725-1863) GregoryN. Evon 83 Portrait of a Tokugawa Outcaste Community Timothy D. Amos 109 -

History of Badminton

Facts and Records History of Badminton In 1873, the Duke of Beaufort held a lawn party at his country house in the village of Badminton, Gloucestershire. A game of Poona was played on that day and became popular among British society’s elite. The new party sport became known as “the Badminton game”. In 1877, the Bath Badminton Club was formed and developed the first official set of rules. The Badminton Association was formed at a meeting in Southsea on 13th September 1893. It was the first National Association in the world and framed the rules for the Association and for the game. The popularity of the sport increased rapidly with 300 clubs being introduced by the 1920’s. Rising to 9,000 shortly after World War Π. The International Badminton Federation (IBF) was formed in 1934 with nine founding members: England, Ireland, Scotland, Wales, Denmark, Holland, Canada, New Zealand and France and as a consequence the Badminton Association became the Badminton Association of England. From nine founding members, the IBF, now called the Badminton World Federation (BWF), has over 160 member countries. The future of Badminton looks bright. Badminton was officially granted Olympic status in the 1992 Barcelona Games. Indonesia was the dominant force in that first Olympic tournament, winning two golds, a silver and a bronze; the country’s first Olympic medals in its history. More than 1.1 billion people watched the 1992 Olympic Badminton competition on television. Eight years later, and more than a century after introducing Badminton to the world, Britain claimed their first medal in the Olympics when Simon Archer and Jo Goode achieved Mixed Doubles Bronze in Sydney. -

Assessment of Arterial Structure and Function in South Asian Ischaemic Stroke Survivors in the United Kingdom

Original Thesis for the Degree of Doctor of Medicine (University of Birmingham) ASSESSMENT OF ARTERIAL STRUCTURE AND FUNCTION IN SOUTH ASIAN ISCHAEMIC STROKE SURVIVORS IN THE UNITED KINGDOM Dr. Herath Mudiyanselage Ashan Indika Gunarathne M.B.B.S, M.R.C.P (U.K ) Specialist Registrar in Cardiology, East Midlands Deanery & Honorary Lecturer in Medicine, University of Birmingham March 2012 ii University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. 2 of 625 Copyright statement Copyright in text of this thesis rests with the Author. Copies (by any process) either in full, or in extracts, may be made only in accordance with the instructions given by the author and the University of Birmingham. This page must form part of any such copies made. Further copies (by any process) of copies made in accordance with such instructions may not be made without the permission (in writing) of the author. The ownership of any intellectual property rights which may be described in this thesis is vested in the University of Birmingham, subject to any prior agreement to the contrary, and may not be made for use by third parties without the written permission of the University, which will prescribe the terms and conditions of any such agreement. -

Volume 11 JNCOLCTL Final Online.Pdf

Journal of the National Council of Less Commonly Taught Languages Vol. 11 Spring, 2012 Danko Šipka, Editor Antonia Schleicher, Managing Editor Charles Schleicher, Copy Editor Nyasha Gwaza, Production Editor Kevin Barry, Production Assistant The development of the Journal of the National Council of Less Commonly Taught Languages is made possible in part through a grant from the U.S. Department of Education Please address enquiries concerning advertising, subscriptions and issues to the NCOLCTL Secretariat at the following address: National African Language Resource Center 4231 Humanities Building, 455 N. Park St., Madison, WI 53706 Copyright © 2012, National Council of Less Commonly Taught Languages (NCOLCTL) iii The Journal of the National Council of Less Commonly Taught Languages, published annually by the Council, is dedicated to the issues and concerns related to the teaching and learning of Less Commonly Taught Languages. The Journal primarily seeks to address the interests of language teachers, administrators, and researchers. Arti- cles that describe innovative and successful teaching methods that are relevant to the concerns or problems of the profession, or that report educational research or experimentation in Less Commonly Taught Languages are welcome. Papers presented at the Council’s annual con- ference will be considered for publication, but additional manuscripts from members of the profession are also welcome. Besides the Journal Editor, the process of selecting material for publication is overseen by the Advisory Editorial Board, which con- sists of the foremost scholars, advocates, and practitioners of LCTL pedagogy. The members of the Board represent diverse linguistic and geographical categories, as well as the academic, government, and business sectors. -

From Colonial Segregation to Postcolonial ‘Integration’ – Constructing Ethnic Difference Through Singapore’S Little India and the Singapore ‘Indian’

FROM COLONIAL SEGREGATION TO POSTCOLONIAL ‘INTEGRATION’ – CONSTRUCTING ETHNIC DIFFERENCE THROUGH SINGAPORE’S LITTLE INDIA AND THE SINGAPORE ‘INDIAN’ ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy IN THE UNIVERSITY OF CANTERBURY BY SUBRAMANIAM AIYER UNIVERSITY OF CANTERBURY 2006 ---------- Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ABSTRACT 1 INTRODUCTION 3 Thesis Argument 3 Research Methodology and Fieldwork Experiences 6 Theoretical Perspectives 16 Social Production of Space and Social Construction of Space 16 Hegemony 18 Thesis Structure 30 PART I - SEGREGATION, ‘RACE’ AND THE COLONIAL CITY Chapter 1 COLONIAL ORIGINS TO NATION STATE – A PREVIEW 34 1.1 Singapore – The Colonial City 34 1.1.1 History and Politics 34 1.1.2 Society 38 1.1.3 Urban Political Economy 39 1.2 Singapore – The Nation State 44 1.3 Conclusion 47 2 INDIAN MIGRATION 49 2.1 Indian migration to the British colonies, including Southeast Asia 49 2.2 Indian Migration to Singapore 51 2.3 Gathering Grounds of Early Indian Migrants in Singapore 59 2.4 The Ethnic Signification of Little India 63 2.5 Conclusion 65 3 THE CONSTRUCTION OF THE COLONIAL NARRATIVE IN SINGAPORE – AN IDEOLOGY OF RACIAL ZONING AND SEGREGATION 67 3.1 The Construction of the Colonial Narrative in Singapore 67 3.2 Racial Zoning and Segregation 71 3.3 Street Naming 79 3.4 Urban built forms 84 3.5 Conclusion 85 PART II - ‘INTEGRATION’, ‘RACE’ AND ETHNICITY IN THE NATION STATE Chapter -

SPAFA Digest 1990, Vol 11, No. 3

39 (Symbolic Communication in Theatre: A Malaysian Chinese Case by Dr. Chua Soo Pong Theatrical event in Asian Examination of the details of the feelings of the Chinese community in societies has never been a purely structural processes in the artistic Malaysia. But they also reflect the artistic event. It usually has several production of the arts could locate awareness of the Chinese artistes in functions simultaneously. Subli in the specific issues in the wider social stating their inspiration to promote Philippines, Wayang Purwa in Java, context. Malay, Indian, and Chinese dance on Chinese opera in Singapore, Mayong This paper is based on personal equal footing. It is clear that the in Kelantan, or Lakorn Chatri in involvement as adjudicator in the Chinese artistes would prefer the art Thailand, all demonstrate the fact four dance festivals (1983, 1984, 1987, forms of the various ethnic groups to that theatrical events in the region 1989) organized by a number of be developed side by side with one serve a variety of political, social or Chinese cultural organizations in another. religious purposes much more expli- Malaysia and in the author's long citly than the art forms in the West. time observations and research on Gathering in Penang Anthropologists of the art and dance in Malaysia. In this article expressive culture have in recent years the author will focus on three areas. The last two days of 1983 have advanced their studies and proposed It provides an overview of the been most exciting for the dance several approaches in the analysis of festivals organized in the last few audience in Penang. -

Nhb13093018.Pdf

Annual Report 2012/2013 CONTENTS 2 Highlights for FY2012 14 Board Members 16 Corporate Information 17 Organisational Structure 18 Corporate Governance 20 Grants & Capability Development 24 Giving 32 Donations & Acquisitions 38 Publications FY2012 was an exciting year of new developments. On 1 November 2012, we came under a new ministry – the Ministry of Culture, Community and Youth. Under the new ministry, we aspire 40 Financial Statements to deepen our conversations and engagements with various sectors. We will continue to nurture Statement by Board Members an appreciation for Singapore’s diverse and multicultural heritage and provide platforms for Independent Auditors’ Report community involvement. Financials A new family member, the Language Council joined the NHB family and we warmly welcome Notes to Financial Statements them. Language is closely linked to one’s heritage and the work that the LCS does will allow NHB to be more synergistic in our heritage offerings for Singaporeans. In FY2012, we launched several new initiatives. Of particular significance was the launch of Our Museum @ Taman Jurong – the first community museum in Singapore’s heartlands. The Malay Heritage Centre was re-opened with a renewed focus on Kampong Gelam, and the contributions of the local Malay community. The Asian Civilisations Museum also announced a new extension, which will allow for more of our National Collection to be displayed. Community engagement remained a priority as we stepped up our efforts to engage Singaporeans from all walks of life – heritage enthusiasts, corporations, interest groups, volunteer guides, patrons and many more, joined us in furthering the heritage cause. Their stories and memories were shared and incorporated into a wide range of offerings including community exhibitions and events, heritage trails, merchandise and e-books. -

Diversities in Cognitive Approach

DIVERSITIES IN COGNITIVE APPROacH MAP maKING AND CARTOGRAPHIC TRadITIONS FROM THE INDIAN OCEAN REGION 4 Time Space Directions Designed by Soumyadip Ghosh © Ambedkar University Delhi All rights reserved AMBEDKAR UNIVERSITY DELHI CENTRE OF COmmuNITY KNOWLEDGE LOTHIAN ROad, KASHMERE GATE, DELHI 110006 TELEPHONE : +91-11-23863740/43 FAX : +91-11-23863742 EmaIL: [email protected], [email protected] Time Space Directions. Delhi, Neeta Press, Shed- 19 DSIDC Industrial Complex, Dakshinpur, ND 62 2014 -1st ed. HISTORY ; DESIGN; MAPS; CARTOGRAPHY; INDIAN OCEAN About The Centre for Community Knowledge The Centre for Community Knowledge (CCK) has been planned as a premier institutional platform in India in interdisciplinary areas of Social Sciences, to link academic research and teaching with dispersed work on Community Knowledge. At a time when communities are faced with multiple challenges, the Centre for Community Knowledge, through its interdisciplinary approach, documents, studies and disseminates the praxis of community knowledge, so as to improve our understandings of our living heritage, and integrate community-based knowledge in the available alternatives. Drawn from living experience, and mostly unwritten, oral and practice based, community knowledge can play a crucial role in these transformative times in a number of areas, including the empowerment of marginal communities, adapting to environmental impacts and changes in public policy. The Centre also aims to foster a multidisciplinary study of marginal knowledge traditions in collaboration -

Chinese Literature in the Second Half of a Modern Century: a Critical Survey

CHINESE LITERATURE IN THE SECOND HALF OF A MODERN CENTURY A CRITICAL SURVEY Edited by PANG-YUAN CHI and DAVID DER-WEI WANG INDIANA UNIVERSITY PRESS • BLOOMINGTON AND INDIANAPOLIS William Tay’s “Colonialism, the Cold War Era, and Marginal Space: The Existential Condition of Five Decades of Hong Kong Literature,” Li Tuo’s “Resistance to Modernity: Reflections on Mainland Chinese Literary Criticism in the 1980s,” and Michelle Yeh’s “Death of the Poet: Poetry and Society in Contemporary China and Taiwan” first ap- peared in the special issue “Contemporary Chinese Literature: Crossing the Bound- aries” (edited by Yvonne Chang) of Literature East and West (1995). Jeffrey Kinkley’s “A Bibliographic Survey of Publications on Chinese Literature in Translation from 1949 to 1999” first appeared in Choice (April 1994; copyright by the American Library Associ- ation). All of the essays have been revised for this volume. This book is a publication of Indiana University Press 601 North Morton Street Bloomington, IN 47404-3797 USA http://www.indiana.edu/~iupress Telephone orders 800-842-6796 Fax orders 812-855-7931 Orders by e-mail [email protected] © 2000 by David D. W. Wang All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Association of American University Presses’ Resolution on Permissions constitutes the only exception to this prohibition. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences— Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. -

Chinas Ballartisten Überlegen Länderkampf Deutschland~ China Endete 0:7

Chinas Ballartisten überlegen Länderkampf Deutschland~ China endete 0:7 Der Vergleich mit Zirkusartisten drängte sich einem klaren 0:7. 0:14 Er. gebnis aus. Allein Die Ergebnisse im Einzelnen: dem Zuschauer auf. wenn er die Spiele der das 2. Herren-Doppel mit Klauer/Treitinger chinesischen Ballartisten gegen die deut konnte die chinesischen Gegner in die Nähe 1. HE: Schnaase - Laan Jin 4: 15. 7:15 . 2. HE : sche Badminton-Elite betrachtete. Bei schier eines Satzverlustes bringen. indem sie 12 Rost-Han Jian 2:15. 10:15. DE : Schmieder unerreichbaren Bällen wurde der Arm plötz• Punkte erzielten. So zeichnete sich dieses Xu Rong 1:11 . 1 :11. 1. HD: Maywald/ Zwiebler lich doppelt so lang, die Beine doppelt so Spiel auch durch die interessantesten Ball - Yao Ximing (?) 0:2 Sätze: 2. HD : Klauer/ hoch oder die Spieler tauchten auf den wechsel aus und die jungen Deutschen konn Treitinger - Lin Jiangli / Chen Chanjie 12 :15. Boden und die verblüfften Gegner schauten ten diesen Satz in etwa ausgeglichen gestal 4: 15. DD: Schmieder/ Dorrenbach - Liu Xia/ verwundert dem Return nach. unfähig zur ten. Die zahlreichen Zuschauer waren begei Zhang Ailing 6:15. 8:15. M : Maywald / Splett Reaktion. stert. In allen anderen Spielen waren die Chi - Sun Zhian / Zhang Ailing 6:15. 1:15 . Natürlich wurde nicht jeder Ballwechsel nesen deutlich überlegen. so daß der Länder• derart beendet, dennoch drückt sich die kampf bereits nach 135 Minuten beendet 1. Barsch deutliche Überlegenheit der Chinesen in war. 17. Internationales Badminton Ehepaarturnier in Solingen Brigitte ynd Dieter Prax (SV Unkel) zum 5. Male Sieger Die 17. -

Madrasah: Dari Niz}A>M Iyyah Hingga Pesisiran Jawa Mahfud Junaedi

Nadwa | Jurnal Pendidikan Islam Vol. 8, Nomor 1, April 2014 Madrasah: dari Niz}a>miyyah hingga Pesisiran Jawa Mahfud Junaedi Institut Agama Islam Negeri Walisongo Semarang Email: [email protected] Abstract Growth and development in the Coastal Java madrasah in the early twentieth cen- tury until now generally spearheaded by scholars/religious leaders who graduated in Islamic centers in the Middle East. At first they established the boarding school, followed by the establishment of madrasah to the coast of Java can be regarded as children of a boarding school. The educational institutions have bonding formation of madrasah was first built by Niz{am al-Mulk in Baghdad in 1057, later known as madrasah Niz{amiyah. This school is an educational institution that aims to teach Fiqh Sunni schools. Institutions of higher education has become one of the eleventh century and became the blueprint for the development of similar madrasah in the Islamic world. Historically, madrasah in Java can not be separated from the Middle East, especially the relationship Haramayn scholars of al-Azhar and Cairo with the students in Java, Indonesia. Keywords: madrasah, Coastal Java, Madrasah Niz{amiyah, scholar Abstrak Pertumbuhan dan perkembangan madrasah di Pesisir Jawa pada awal abad ke- XX hingga kini, umumnya dipelopori oleh para kiai atau tokoh agama yang menamatkan pendidikan di pusat-pusat Islam tersebut. Pada awalnya mereka mendirikan pondok pesantren, lalu diikuti dengan pendirian madrasah, sehingga madrasah di pesisir Jawa bisa dikatakan sebagai anak-anak pesantren. Lembaga pendidikan ini memiliki ikatan dengan madrasah pertama kali dibangun oleh Niz{am al-Mulk di Baghdad pada tahun 1057, kemudian dikenal dengan madrasah Niz{amiyah. -

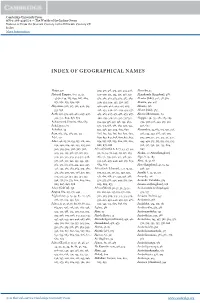

Index of Geographical Names

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-42465-3 — The Worlds of the Indian Ocean Volume 2: From the Seventh Century to the Fifteenth Century CE Index More Information INDEX OF GEOGRAPHICAL NAMES Abaya, 571 309, 317, 318, 319, 320, 323, 328, Akumbu, 54 Abbasid Empire, 6–7, 12, 17, 329–370, 371, 374, 375, 376, 377, Alamkonda (kingdom), 488 45–70, 149, 185, 639, 667, 669, 379, 380, 382, 383, 384, 385, 389, Alaotra (lake), 401, 411, 582 671, 672, 673, 674, 676 390, 393, 394, 395, 396, 397, Alasora, 414, 427 Abyssinia, 306, 317, 322, 490, 519, 400, 401, 402, 409, 415, 425, Albania, 516 533, 656 426, 434, 440, 441, 449, 454, 457, Albert (lake), 365 Aceh, 198, 374, 425, 460, 497, 498, 463, 465, 467, 471, 478, 479, 487, Alborz Mountains, 69 503, 574, 609, 678, 679 490, 493, 519, 521, 534, 535–552, Aleppo, 149, 175, 281, 285, 293, Achaemenid Empire, 660, 665 554, 555, 556, 557, 558, 559, 569, 294, 307, 326, 443, 519, 522, Achalapura, 80 570, 575, 586, 588, 589, 590, 591, 528, 607 Achsiket, 49 592, 596, 597, 599, 603, 607, Alexandria, 53, 162, 175, 197, 208, Acre, 163, 284, 285, 311, 312 608, 611, 612, 615, 617, 620, 629, 216, 234, 247, 286, 298, 301, Adal, 451 630, 637, 647, 648, 649, 652, 653, 307, 309, 311, 312, 313, 315, 322, Aden, 46, 65, 70, 133, 157, 216, 220, 654, 657, 658, 659, 660, 661, 662, 443, 450, 515, 517, 519, 523, 525, 230, 240, 284, 291, 293, 295, 301, 668, 678, 688 526, 527, 530, 532, 533, 604, 302, 303, 304, 306, 307, 308, Africa (North), 6, 8, 17, 43, 47, 49, 607 309, 313, 315, 316, 317, 318, 319, 50, 52, 54, 70, 149, 151, 158,