The Prospects and Sources of New Delhi's Nuclear Weapons Program

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

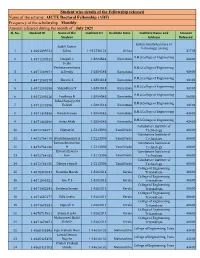

Student Wise Details of the Fellowship Released Name of the Scheme

Student wise details of the Fellowship released Name of the scheme: AICTE Doctoral Fellowship (ADF) Frequency of the scholarship –Monthly Amount released during the month of : July 2021 Sl. No. Student ID Name of the Institute ID Institute State Institute Name and Amount Student Address Released Indira Gandhi Institute of Sushil Kumar Technology, Sarang 1 1-4064399722 Sahoo 1-412736121 Orissa 31703 B.M.S.College of Engineering 2 1-4071237529 Deepak C 1-5884543 Karnataka 43400 Perla Venkatasreenivasu B.M.S.College of Engineering 3 1-4071249071 la Reddy 1-5884543 Karnataka 43400 B.M.S.College of Engineering 4 1-4071249170 Shruthi S 1-5884543 Karnataka 43400 B.M.S.College of Engineering 5 1-4071249196 Vidyadhara V 1-5884543 Karnataka 43400 B.M.S.College of Engineering 6 1-4071249216 Pruthvija B 1-5884543 Karnataka 86800 Tulasi Naga Jyothi B.M.S.College of Engineering 7 1-4071249296 Kolanti 1-5884543 Karnataka 43400 B.M.S.College of Engineering 8 1-4071448346 Manali Raman 1-5884543 Karnataka 43400 B.M.S.College of Engineering 9 1-4071448396 Anisa Aftab 1-5884543 Karnataka 43400 Coimbatore Institute of 10 1-4072764071 Vijayan M 1-5213396 Tamil Nadu Technology 40600 Coimbatore Institute of 11 1-4072764119 Sivasubramani P A 1-5213396 Tamil Nadu Technology 40600 Ramasubramanian Coimbatore Institute of 12 1-4072764136 M 1-5213396 Tamil Nadu Technology 40600 Eswara Eswara Coimbatore Institute of 13 1-4072764153 Rao 1-5213396 Tamil Nadu Technology 40600 Coimbatore Institute of 14 1-4072764158 Dhivya Priya N 1-5213396 Tamil Nadu Technology 40600 -

Government of India Ministry of Culture Lok Sabha Unstarred Question No.2320 to Be Answered on 09.05.2016

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF CULTURE LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO.2320 TO BE ANSWERED ON 09.05.2016 MEMORIALS IN THE NAME OF FORMER PRIME MINISTERS 2320. SHRI C.R. PATIL Will the Minister of CULTURE be pleased to state: (a) whether the Government makes the nomenclature of the memorials in name of former Prime Ministers and other politically, socially or culturally renowned persons and if so, the details thereof; (b) whether the State Government of Gujarat has requested the Ministry to pay Rs. One crore as compensation for acquiring Samadhi Land - Abhay Ghat to build a memorial in the name of Ex-PM Shri Morarji Desai and if so, the details thereof; (c) whether the Government had constituted a Committee in past to develop a memorial on his Samadhi; and (d) the action taken by the Government to acquire the Sabarmati Ashram Gaushala Trust land to make memorial in the name of the said former Prime Minister? ANSWER MINISTER OF STATE (INDEPENDENT CHARGE) FOR CULTURE & TOURISM AND MINISTER OF STATE FOR CIVIL AVIATION. DR. MAHESH SHARMA (a) Yes, Madam. The nomenclature of the memorials is given by the Government with the approval of Union Cabinet. For example: Samadhi of Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru is known as Shanti Vana, Samadhi of Mahatama Gandhi is known as Rajghat, Samadhi of late Shri Lal Bahadur Shastri is known as Vijay Ghat, Samadhi of Ch. Charan Singh is known as Kisan Ghat, Samadhi of Babu Jagjivan Ram is known as Samta Sthal, Samadhi of late Smt. Indira Gandhi is known as Shakti Sthal, Samadhi of Devi Lal is known as Sangharsh Sthal, Samadhi of late Shri Rajiv Gandhi is known as Vir Bhumi and so on. -

9 Post & Telecommunications

POST AND TELECOMMUNICATIONS 441 9 Post & Telecommunications ORGANISATION The Office of the Director General of Audit, Post and Telecommunications has a chequered history and can trace its origin to 1837 when it was known as the Office of the Accountant General, Posts and Telegraphs and continued with this designation till 1978. With the departmentalisation of accounts with effect from April 1976 the designation of AGP&T was changed to Director of Audit, P&T in 1979. From July 1990 onwards it was designated as Director General of Audit, Post and Telecommunications (DGAP&T). The Central Office which is the Headquarters of DGAP&T was located in Shimla till early 1970 and thereafter it shifted to Delhi. The Director General of Audit is assisted by two Group Officers in Central Office—one in charge of Administration and other in charge of the Report Group. However, there was a difficult period from November 1993 till end of 1996 when there was only one Deputy Director for the Central office. The P&T Audit Organisation has 16 branch Audit Offices across the country; while 10 of these (located at Chennai, Delhi, Hyderabad, Kapurthala, Lucknow, Mumbai, Nagpur, Patna and Thiruvananthapuram as well as the Stores, Workshop and Telegraph Check Office, Kolkata) were headed by IA&AS Officers of the rank of Director/ Dy. Director. The charges of the remaining branch Audit Offices (located at Ahmedabad, Bangalore, Bhopal, Cuttack, Jaipur and Kolkata) were held by Directors/ Dy. Directors of one of the other branch Audit Offices (as of March 2006) as additional charge. P&T Audit organisation deals with all the three principal streams of audit viz. -

A Number of Decisions Made by the Rajiv Gandhi Government

Back to the Future: The Congress Party’s Upset Victory in India’s 14th General Elections Introduction The outcome of India’s 14th General Elections, held in four phases between April 20 and May 10, 2004, was a big surprise to most election-watchers. The incumbent center-right National Democratic Alliance (NDA) led by the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), had been expected to win comfortably--with some even speculating that the BJP could win a majority of the seats in parliament on its own. Instead, the NDA was soundly defeated by a center-left alliance led by the Indian National Congress or Congress Party. The Congress Party, which dominated Indian politics until the 1990s, had been written off by most observers but edged out the BJP to become the largest party in parliament for the first time since 1996.1 The result was not a complete surprise as opinion polls did show the tide turning against the NDA. While early polls forecast a landslide victory for the NDA, later ones suggested a narrow victory, and by the end, most exit polls predicted a “hung” parliament with both sides jockeying for support. As it turned out, the Congress-led alliance, which did not have a formal name, won 217 seats to the NDA’s 185, with the Congress itself winning 145 seats to the BJP’s 138. Although neither alliance won a majority in the 543-seat lower house of parliament (Lok Sabha) the Congress-led alliance was preferred by most of the remaining parties, especially the four-party communist-led Left Front, which won enough seats to guarantee a Congress government.2 Table 1: Summary of Results of 2004 General Elections in India. -

India's Agendas on Women's Education

University of St. Thomas, Minnesota UST Research Online Education Doctoral Dissertations in Leadership School of Education 8-2016 The olitP icized Indian Woman: India’s Agendas on Women’s Education Sabeena Mathayas University of St. Thomas, Minnesota, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.stthomas.edu/caps_ed_lead_docdiss Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Mathayas, Sabeena, "The oP liticized Indian Woman: India’s Agendas on Women’s Education" (2016). Education Doctoral Dissertations in Leadership. 81. https://ir.stthomas.edu/caps_ed_lead_docdiss/81 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Education at UST Research Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Education Doctoral Dissertations in Leadership by an authorized administrator of UST Research Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Politicized Indian Woman: India’s Agendas on Women’s Education A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE COLLEGE OF EDUCATION, LEADERSHIP, AND COUNSELING OF THE UNIVERSITY OF ST. THOMAS by Sabeena Mathayas IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF EDUCATION Minneapolis, Minnesota August 2016 UNIVERSITY OF ST. THOMAS The Politicized Indian Woman: India’s Agendas on Women’s Education We certify that we have read this dissertation and approved it as adequate in scope and quality. We have found that it is complete and satisfactory in all respects, and that any and all revisions required by the final examining committee have been made. Dissertation Committee i The word ‘invasion’ worries the nation. The 106-year-old freedom fighter Gopikrishna-babu says, Eh, is the English coming to take India again by invading it, eh? – Now from the entire country, Indian intellectuals not knowing a single Indian language meet in a closed seminar in the capital city and make the following wise decision known. -

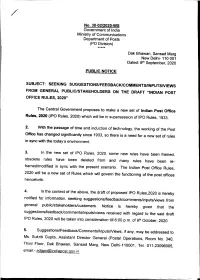

Public Notice-Merged.Pdf

No. 30-02/202 0-ws Government of lndia Ministry of Communications Department of Posts (PO Division) Dak Bhawan, Sansad Marg New Delhi- 110 001 Dated: 8th September, 2020 PUBLIC NOTICE SUBJECT: SEEKtNG suGGEsrloNs/FEEDBAcK/coMMENTS/|NpursrurEWs FROM GENERAL PUBLIC/STAKEHOLDERS ON THE DRAFT "INDIAN POST OFFICE RULES,2020" The central Government proposes to make a new set of lndian post office Rules' 2020 (lPo Rules, 2020) which wiil be in supersession of lpo Rures, 1933. passage 2- with the of time and induction of technorogy, the working of the post office has changed significanfly since 1933, so there is a need for a new set of rules in sync with the today's environment. 3. ln the new set of rpo Rures, 2020. some new rures have been framed, obsolete rules have been dereted from and many rures have been re- framed/modified in sync with the present scenario. The lndian post office Rules, 2020 will be a new set of Rures which wiil govern the functioning of the post offices henceforth. 4. ln the context of the above, the draft of proposed rpo Rures,2020 is hereby notified for information, seeking suggestions/feedbacucomments/inputs/views from general public/stakehorders/customers. Notice is hereby given that the suggestions/feedbacucomments/inputs/views received with regard to the said draft lPo Rules, 2020 will be taken into consideration tilr 6:00 p.m. of 9th october, 2020. 5. Suggestions/Feedback/comments/rnputsA/iews, if any, may be addressed to Ms. Sukriti Gupta, Assistant Director General (postal Operations, Room No. 340, Third Floor, Dak Bhawan, sansad Marg, New Derhi-i10001 , Ter. -

POSTAL SAVINGS Reaching Everyone in Asia

POSTAL SAVINGS Reaching Everyone in Asia Edited by Naoyuki Yoshino, José Ansón, and Matthias Helble ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK INSTITUTE Postal Savings - Reaching Everyone in Asia Edited by Naoyuki Yoshino, José Ansón, and Matthias Helble ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK INSTITUTE © 2018 Asian Development Bank Institute All rights reserved. First printed in 2018. ISBN: 978 4 89974 083 4 (Print) ISBN: 978 4 89974 084 1 (PDF) The views in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Asian Development Bank Institute (ADBI), its Advisory Council, ADB’s Board or Governors, or the governments of ADB members. ADBI does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this publication and accepts no responsibility for any consequence of their use. ADBI uses proper ADB member names and abbreviations throughout and any variation or inaccuracy, including in citations and references, should be read as referring to the correct name. By making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area, or by using the term “recognize,” “country,” or other geographical names in this publication, ADBI does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Users are restricted from reselling, redistributing, or creating derivative works without the express, written consent of ADBI. ADB recognizes “China” as the People’s Republic of China. Note: In this publication, “$” refers to US dollars. Asian Development Bank Institute Kasumigaseki Building 8F 3-2-5, Kasumigaseki, Chiyoda-ku Tokyo 100-6008, Japan www.adbi.org Contents List of illustrations v List of contributors ix List of abbreviations xi Introduction 1 Naoyuki Yoshino, José Ansón, and Matthias Helble PART I: Global Overview 1. -

Manmohan Singh 1

Manmohan Singh 1 As finance minister in Narasimha Rao's government of the '90s, Manmohan Singh helmed reforms that liberalized India's economy, changing it in a fundamental way. Singh discusses India's history of industrial policy and economic reform, the impact of globalization, and the role of government in the Indian economy. India's Central Planning: Nehru's Vision and the Reality INTERVIEWER: Nehru wrote that socialism has science and logic on its side. What did he mean by that? MANMOHAN SINGH: Nehru was a rational thinker, and he wanted to apply science and technologies to solve the living problems of our time. In India, the foremost problem was India's economic [and] social backwardness [and] the great mass poverty that prevailed at the time of independence. Nehru's vision was to get rid of that chronic poverty, ignorance, and disease, making use of modern science and technology. INTERVIEWER: The central aim was to modernize, industrializing in one generation. Was that a crazy idea or a good idea? MANMOHAN SINGH: Elsewhere in the world, there are instances [of this happening]. The Soviet Union industrialized itself with a single generation. The industrial revolution in England you can break down into phases. A lot of structural changes took place in one generation, which later on became irreversible. That was Nehru's vision. His vision was to industrialize India, to urbanize India, and in the process he hoped that we would create a new society—more rational, more humane, less ridden by caste and religious sentiments. That was the grand vision that Nehru had. -

Advancing Financial Inclusion Through Access to Insurance: the Role Of

Advancing financial inclusion through access to insurance: the role of postal networks Published by the Universal Postal Union (UPU) Berne, Switzerland and by the International Labour Organization (ILO) Geneva, Switzerland. Printed in Switzerland by the printing services of the International Bureau of the UPU. Copyright © 2016 UPU / ILO All rights reserved Except as otherwise indicated, the copyright in this publication is owned by the UPU and the ILO. Reproduction is authorized for non-commercial purposes, subject to proper acknowledgement of the source. This authorization does not extend to any material identified in this publication as being the copyright of a third party. Authorization to reproduce such third party materials must be obtained from the copyright holders concerned. AUTHOR: Guilherme Suedekum TITLE: Advancing financial inclusion through access to insurance: the role of postal networks ISBN: 978-92-95025-84-4 DESIGN: UPU Graphic Unit CONTACT: Nils Clotteau, UPU, [email protected] Craig Churchill, ILO, [email protected] COVER PICTURE: © 2009 Indian Post This study is the result of a joint effort between the International Labour Organization (ILO) and the Universal Postal Union (UPU). It was prepared by Guilherme Suedekum, financial inclusion independent consultant, with the guidance and advice of Craig Churchill, team leader of the ILO’s Impact Insurance Facility, and Nils Clotteau, Acknowledgements Partnerships and Resource Mobilization Expert at the UPU. The team is especially grateful to Dauren Turysbekov, Director of the Department of External Affairs at Kazpost, Michel Kabré, Director of Financial Services at SONAPOST, Titus Juma, Director of Payment Services at the Postal Corporation of Kenya, M’hamed El-Moussaoui, Assistant Director General of Al Barid Bank, and Rajagopal Krishnaswamy, Managing Director at Professional Life Assurance. -

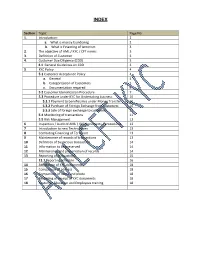

2 A. What Is Money Laundering 2 B. What Is Financing of Terrorism 3 2

INDEX Section Topic Page No 1. Introduction: 2 a. What is money laundering 2 b. What is Financing of terrorism 3 2. The objective of AML / KYC / CFT norms 3 3. Definition of Customer 3 4. Customer Due Diligence (CDD) 3 4.1 General Guidelines on CDD 3 5 KYC Policy 4 5.1 Customer Acceptance Policy 4 a. General 4 b. Categorization of Customers 5 c. Documentation required 6 5.2 Customer Identification Procedure 7 5.3 Procedure under KYC for Undertaking business 10 5.3.1 Payment to beneficiaries under Money Transfer 10 5.3.2 Purchase of Foreign Exchange from customers 10 5.3.3 Sale of foreign exchange to customers 11 5.4 Monitoring of transactions 11 5.5 Risk Management 12 6 Inspection / Audit of AML \ KYC documents / procedures 13 7 Introduction to new Technologies 13 8 Combating Financing of Terrorism 13 9 Maintenance of records of transactions 13 10 Definition of Suspicious transaction 14 11 Information to be preserved 14 12 Maintenance and preservation of records 14 13 Reporting of transactions 15 13.1 Reporting schedule 16 14 Attestation of KYC documents 18 15 Comparison of address 18 16 Comparison of name and photo 18 17 Recording of receipt of KYC documents 18 18 Customer Education and Employees training 18 Guidelines on Know Your Customer (KYC) Norms / Anti-Money Laundering (AML) Standards / Combating Financing of Terrorism (CFT) Norms under Prevention of Money Laundering Act, PMLA, 2002 as amended by Prevention of Money Laundering (Amendment) Act, 2009 for International Money Transfer Services(Inward) under the Money Transfer Service Scheme (MTSS) and Money Changing Services in India Post 1. -

Charismatic Leadership in India

CHARISMATIC LEADERSHIP IN INDIA: A STUDY OF JAWAHARLAL NEHRU, INDIRA GANDHI, AND RAJIV GANDHI By KATHLEEN RUTH SEIP,, Bachelor of Arts In Arts and Sciences Oklahoma State University Stillwater, Oklahoma 1984 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS December, 1987 1L~is \<1ql SLfttk. ccp. ';l -'r ·.' .'. ' : . ,· CHARISMATIC LEADERSHIP IN INDIA: A STUDY OF JAWAHARLAL NEHRU, INDIRA GANDHI, AND RAJIV GANDHI Thesis Approved: __ ::::'.3_:~~~77----- ---~-~5-YF"' Av~~-------; , -----~-- ~~-~--- _____ llJ12dJ1_4J:k_ll_iJ.4Uk_ Dean of the Graduate College i i 1291053 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to express sincere appreciation to Professor Harold Sare for his advice, direction and encouragement in the writing of this thesis and throughout my graduate program. Many thanks also go to Dr. Joseph Westphal and Dr. Franz van Sauer for serving on my graduate committee and offering their suggestions. I would also like to thank Karen Hunnicutt for assisting me with the production of the thesis. Without her patience, printing the final copy would have never been possible. Above all, I thank my parents, Robert and Ruth Seip for their faith in my abilities and their constant support during my graduate study. i i i TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. JAWAHARLAL NEHRU . 20 The Institutionalization of Charisma. 20 I I I . INDIRA GANDHI .... 51 InstitutionaliZ~tion without Charisma . 51 IV. RAJIV GANDHI ..... 82 The Non-charismatic Leader •. 82 v. CONCLUSION 101 WORKS CITED . 106 iv CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION The leadership of India has been in the hands of one family since Independence with the exception of only a few years. -

LOK SABHA DEBATES (English .Version)

Nlatla SerIeI, Vol. I. No 4 Tha.... ', DeeemIJer 21. U89 , A..... ' ... 30. I'll (SUa) LOK SABHA DEBATES (English .Version) First Seai.D (Nlntb Lok Sabba) (Yol. I COlJtairu N08. 1 to 9) LOI: SABRA SECRE1'AlUAT NEW DELHI Price, 1 Itt. 6.00 •• , • .' C , '" ".' .1. t; '" CONTENTS [Ninth Series, VoL /, First Session, 198911911 (Saka)] No. 4, Thursday, December 21, 1989/Agrahayana 30, 1911 (Saka) CoLUMNS Members Sworn 1 60 Assent to Bills 1--2 Introduction of Ministers 2-16 Matters Under Rule 377 16-20 (i) Need to convert the narrow gauge railway 16 line between Yelahanka and Bangarpet in Karnataka into bread gauge tine Shri V. Krishna Rao (ii) Need to ban the m~nufadure and sale of 16-17 Ammonium Sulphide in the country Shri Ram Lal Rahi (iii) Need to revise the Scheduled Castes/ 17 Sched uled Tribes list and provide more facilities to backward classes Shri Uttam Rathod (iv) Need to 3et up the proposed project for 18 exploitation of nickel in Sukinda region of Orissa Shri Anadi Charan Das (v) Need to set up full-fledged Doordarshan 18 Kendras in towns having cultural heritage, specially at Varanasi in Uttar Pradesh Shri Anil Shastri (ii) CoLUMNS (vi) Need to set up Purchase Centres in the cotton 18-19 producing districts of Madhya Pradesh Shri Laxmi Narain Pandey (vii) Need for steps to maintain ecological 19 balance in the country Shri Ramashray Prasad Singh (viii) Need to take measures for normalising 19-20 relations between India and Pakistan Prof. Saifuddin Soz (;x) Need to take necessary steps for an amicable 20 solution of the Punjab problem Shri Mandhata Singh Motion of Confidence in the Council of Ministers 20-107 110-131 Shri Vishwanath Pratap Singh 20-21 116-131 Shri A.R.