A Number of Decisions Made by the Rajiv Gandhi Government

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

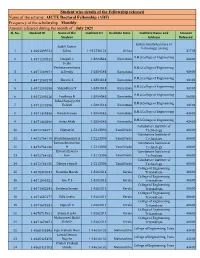

Student Wise Details of the Fellowship Released Name of the Scheme

Student wise details of the Fellowship released Name of the scheme: AICTE Doctoral Fellowship (ADF) Frequency of the scholarship –Monthly Amount released during the month of : July 2021 Sl. No. Student ID Name of the Institute ID Institute State Institute Name and Amount Student Address Released Indira Gandhi Institute of Sushil Kumar Technology, Sarang 1 1-4064399722 Sahoo 1-412736121 Orissa 31703 B.M.S.College of Engineering 2 1-4071237529 Deepak C 1-5884543 Karnataka 43400 Perla Venkatasreenivasu B.M.S.College of Engineering 3 1-4071249071 la Reddy 1-5884543 Karnataka 43400 B.M.S.College of Engineering 4 1-4071249170 Shruthi S 1-5884543 Karnataka 43400 B.M.S.College of Engineering 5 1-4071249196 Vidyadhara V 1-5884543 Karnataka 43400 B.M.S.College of Engineering 6 1-4071249216 Pruthvija B 1-5884543 Karnataka 86800 Tulasi Naga Jyothi B.M.S.College of Engineering 7 1-4071249296 Kolanti 1-5884543 Karnataka 43400 B.M.S.College of Engineering 8 1-4071448346 Manali Raman 1-5884543 Karnataka 43400 B.M.S.College of Engineering 9 1-4071448396 Anisa Aftab 1-5884543 Karnataka 43400 Coimbatore Institute of 10 1-4072764071 Vijayan M 1-5213396 Tamil Nadu Technology 40600 Coimbatore Institute of 11 1-4072764119 Sivasubramani P A 1-5213396 Tamil Nadu Technology 40600 Ramasubramanian Coimbatore Institute of 12 1-4072764136 M 1-5213396 Tamil Nadu Technology 40600 Eswara Eswara Coimbatore Institute of 13 1-4072764153 Rao 1-5213396 Tamil Nadu Technology 40600 Coimbatore Institute of 14 1-4072764158 Dhivya Priya N 1-5213396 Tamil Nadu Technology 40600 -

Government of India Ministry of Culture Lok Sabha Unstarred Question No.2320 to Be Answered on 09.05.2016

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF CULTURE LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO.2320 TO BE ANSWERED ON 09.05.2016 MEMORIALS IN THE NAME OF FORMER PRIME MINISTERS 2320. SHRI C.R. PATIL Will the Minister of CULTURE be pleased to state: (a) whether the Government makes the nomenclature of the memorials in name of former Prime Ministers and other politically, socially or culturally renowned persons and if so, the details thereof; (b) whether the State Government of Gujarat has requested the Ministry to pay Rs. One crore as compensation for acquiring Samadhi Land - Abhay Ghat to build a memorial in the name of Ex-PM Shri Morarji Desai and if so, the details thereof; (c) whether the Government had constituted a Committee in past to develop a memorial on his Samadhi; and (d) the action taken by the Government to acquire the Sabarmati Ashram Gaushala Trust land to make memorial in the name of the said former Prime Minister? ANSWER MINISTER OF STATE (INDEPENDENT CHARGE) FOR CULTURE & TOURISM AND MINISTER OF STATE FOR CIVIL AVIATION. DR. MAHESH SHARMA (a) Yes, Madam. The nomenclature of the memorials is given by the Government with the approval of Union Cabinet. For example: Samadhi of Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru is known as Shanti Vana, Samadhi of Mahatama Gandhi is known as Rajghat, Samadhi of late Shri Lal Bahadur Shastri is known as Vijay Ghat, Samadhi of Ch. Charan Singh is known as Kisan Ghat, Samadhi of Babu Jagjivan Ram is known as Samta Sthal, Samadhi of late Smt. Indira Gandhi is known as Shakti Sthal, Samadhi of Devi Lal is known as Sangharsh Sthal, Samadhi of late Shri Rajiv Gandhi is known as Vir Bhumi and so on. -

India: the Weakening of the Congress Stranglehold and the Productivity Shift in India

ASARC Working Paper 2009/06 India: The Weakening of the Congress Stranglehold and the Productivity Shift in India Desh Gupta, University of Canberra Abstract This paper explains the complex of factors in the weakening of the Congress Party from the height of its power at the centre in 1984. They are connected with the rise of state and regional-based parties, the greater acceptability of BJP as an alternative in some of the states and at the Centre, and as a partner to some of the state-based parties, which are in competition with Congress. In addition, it demonstrates that even as the dominance of Congress has diminished, there have been substantial improvements in the economic performance and primary education enrolment. It is argued that V.P. Singh played an important role both in the diminishing of the Congress Party and in India’s improved economic performance. Competition between BJP and Congress has led to increased focus on improved governance. Congress improved its position in the 2009 Parliamentary elections and the reasons for this are briefly covered. But this does not guarantee an improved performance in the future. Whatever the outcomes of the future elections, India’s reforms are likely to continue and India’s economic future remains bright. Increased political contestability has increased focus on governance by Congress, BJP and even state-based and regional parties. This should ensure improved economic and outcomes and implementation of policies. JEL Classifications: O5, N4, M2, H6 Keywords: Indian Elections, Congress Party's Performance, Governance, Nutrition, Economic Efficiency, Productivity, Economic Reforms, Fiscal Consolidation Contact: [email protected] 1. -

Journal of Advances and Scholarly Researches in Allied Education Vol

Journal of Advances and JournalScholarly of Advances and Researches in Scholarly Researches in AlliedAllied Education Education Vol. I V3,, Issue Issue No. 6, VI II, October-2012, ISSN 2230- April7540-2012, ISSN 2230- 7540 REVIEW ARTICLE “A STUDY OF KENGAL HUNUMANTHAIAH’S AN POLITICAL AND SOCIAL THOUGHTS” INTERNATIONALLY INDEXED PEER Study of Political Representations: REVIEWED & REFEREED JOURNAL Diplomatic Missions of Early Indian to Britain www.ignited.in Journal of Advances and Scholarly Researches in Allied Education Vol. IV, Issue No. VIII, October-2012, ISSN 2230-7540 “A Study of Kengal Hunumanthaiah’s Political and Social Thoughts” Deepak Kumar T Research Scholar, Mahatma Jyotiba Phule Rohilkhand University, Barely, UP Abstract – The paper presents attempts to main focus on the governmental factors of Kengal Hanumanthaiah’s. The paper places of interest the participation of Kengal Hanumanthaiah in the independence association and his role in the fusion of Karnataka. The paper represents Kengal Hanumanthaiah’s role in Politics, the administrative dream of Kengal Hanumanthaiah and how the temporal and spatial dimensions got interlinked with politics during his period. The main objective of this paper is to discuss the political and social vision of Kengal Hanumanthaiah in Karnataka. - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - X - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - INTRODUCTION some occasions. Hanumanthaiah clashed with Nehru many times on this issue. His government achieved Kengel Hanumanthaiah was the second Chief Minister the National Economic Growth target at a 15% lower of Mysore State from 30th March 1952 to 19th August outlay. Hanumanthaiah’s period of governance is still 1956. He was the main force behind the construction held in high admiration by the political historians of of the Vidhana Soudha, Bangalore. -

India's Agendas on Women's Education

University of St. Thomas, Minnesota UST Research Online Education Doctoral Dissertations in Leadership School of Education 8-2016 The olitP icized Indian Woman: India’s Agendas on Women’s Education Sabeena Mathayas University of St. Thomas, Minnesota, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.stthomas.edu/caps_ed_lead_docdiss Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Mathayas, Sabeena, "The oP liticized Indian Woman: India’s Agendas on Women’s Education" (2016). Education Doctoral Dissertations in Leadership. 81. https://ir.stthomas.edu/caps_ed_lead_docdiss/81 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Education at UST Research Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Education Doctoral Dissertations in Leadership by an authorized administrator of UST Research Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Politicized Indian Woman: India’s Agendas on Women’s Education A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE COLLEGE OF EDUCATION, LEADERSHIP, AND COUNSELING OF THE UNIVERSITY OF ST. THOMAS by Sabeena Mathayas IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF EDUCATION Minneapolis, Minnesota August 2016 UNIVERSITY OF ST. THOMAS The Politicized Indian Woman: India’s Agendas on Women’s Education We certify that we have read this dissertation and approved it as adequate in scope and quality. We have found that it is complete and satisfactory in all respects, and that any and all revisions required by the final examining committee have been made. Dissertation Committee i The word ‘invasion’ worries the nation. The 106-year-old freedom fighter Gopikrishna-babu says, Eh, is the English coming to take India again by invading it, eh? – Now from the entire country, Indian intellectuals not knowing a single Indian language meet in a closed seminar in the capital city and make the following wise decision known. -

Modi, Social Media, and Competitive Electoral Populism in India

International Journal of Communication 11(2017), 4158–4180 1932–8036/20170005 Fragile Hegemony: Modi, Social Media, and Competitive Electoral Populism in India SUBIR SINHA1 School of Oriental and African Studies, London, UK Direct and unmediated communication between the leader and the people defines and constitutes populism. I examine how social media, and communicative practices typical to it, function as sites and modes for constituting competing models of the leader, the people, and their relationship in contemporary Indian politics. Social media was mobilized for creating a parliamentary majority for Narendra Modi, who dominated this terrain and whose campaign mastered the use of different platforms to access and enroll diverse social groups into a winning coalition behind his claims to a “developmental sovereignty” ratified by “the people.” Following his victory, other parties and political formations have established substantial presence on these platforms. I examine emerging strategies of using social media to criticize and satirize Modi and offering alternative leader-people relations, thus democratizing social media. Practices of critique and its dissemination suggest the outlines of possible “counterpeople” available for enrollment in populism’s future forms. I conclude with remarks about the connection between activated citizens on social media and the fragility of hegemony in the domain of politics more generally. Keywords: Modi, populism, Twitter, WhatsApp, social media On January 24, 2017, India’s ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), proudly tweeted that Narendra Modi, its iconic prime minister of India, had become “the world’s most followed leader on social media” (see Figure 1). Modi’s management of—and dominance over—media and social media was a key factor contributing to his convincing win in the 2014 general election, when he led his party to a parliamentary majority, winning 31% of the votes cast. -

Manmohan Singh 1

Manmohan Singh 1 As finance minister in Narasimha Rao's government of the '90s, Manmohan Singh helmed reforms that liberalized India's economy, changing it in a fundamental way. Singh discusses India's history of industrial policy and economic reform, the impact of globalization, and the role of government in the Indian economy. India's Central Planning: Nehru's Vision and the Reality INTERVIEWER: Nehru wrote that socialism has science and logic on its side. What did he mean by that? MANMOHAN SINGH: Nehru was a rational thinker, and he wanted to apply science and technologies to solve the living problems of our time. In India, the foremost problem was India's economic [and] social backwardness [and] the great mass poverty that prevailed at the time of independence. Nehru's vision was to get rid of that chronic poverty, ignorance, and disease, making use of modern science and technology. INTERVIEWER: The central aim was to modernize, industrializing in one generation. Was that a crazy idea or a good idea? MANMOHAN SINGH: Elsewhere in the world, there are instances [of this happening]. The Soviet Union industrialized itself with a single generation. The industrial revolution in England you can break down into phases. A lot of structural changes took place in one generation, which later on became irreversible. That was Nehru's vision. His vision was to industrialize India, to urbanize India, and in the process he hoped that we would create a new society—more rational, more humane, less ridden by caste and religious sentiments. That was the grand vision that Nehru had. -

The Saffron Wave Meets the Silent Revolution: Why the Poor Vote for Hindu Nationalism in India

THE SAFFRON WAVE MEETS THE SILENT REVOLUTION: WHY THE POOR VOTE FOR HINDU NATIONALISM IN INDIA A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Tariq Thachil August 2009 © 2009 Tariq Thachil THE SAFFRON WAVE MEETS THE SILENT REVOLUTION: WHY THE POOR VOTE FOR HINDU NATIONALISM IN INDIA Tariq Thachil, Ph. D. Cornell University 2009 How do religious parties with historically elite support bases win the mass support required to succeed in democratic politics? This dissertation examines why the world’s largest such party, the upper-caste, Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has experienced variable success in wooing poor Hindu populations across India. Briefly, my research demonstrates that neither conventional clientelist techniques used by elite parties, nor strategies of ideological polarization favored by religious parties, explain the BJP’s pattern of success with poor Hindus. Instead the party has relied on the efforts of its ‘social service’ organizational affiliates in the broader Hindu nationalist movement. The dissertation articulates and tests several hypotheses about the efficacy of this organizational approach in forging party-voter linkages at the national, state, district, and individual level, employing a multi-level research design including a range of statistical and qualitative techniques of analysis. In doing so, the dissertation utilizes national and author-conducted local survey data, extensive interviews, and close observation of Hindu nationalist recruitment techniques collected over thirteen months of fieldwork. BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH Tariq Thachil was born in New Delhi, India. He received his bachelor’s degree in Economics from Stanford University in 2003. -

Sebuah Kajian Pustaka

International Journal of Research in Social Sciences Vol. 9 Issue 2, February2019, ISSN: 2249-2496 Impact Factor: 7.081 Journal Homepage: http://www.ijmra.us, Email: [email protected] Double- Blind Peer Reviewed Refereed Open Access International Journal - Included in the International Serial Directories Indexed & Listed at: Ulrich's Periodicals Directory ©, U.S.A., Open J-Gage as well as in Cabell’s Directories of Publishing Opportunities, U.S.A REFLECTION ON POST INDEPENDENT INDIAN SOCIO-POLITICAL SCENARIO THROUGH THE WORK A SUITABLE BOY BYVIKRAM SETH Dr. Reena Singh Abstract In this paper my aim is to reveal the socio-political scenario of Post Independent India through the novel A Suitable Boy as Vikram Seth did lot of research on this topic sitting in libraries, traveling various places observing social, political culture. Since he had spent half of his life abroad, he had no direct access to the India of fifties, which he has portrayed. As a social realist, Seth mirrors different aspects of the society faithfully. His reflection of the society, its customs and conventions and contemporary events, with vivid details establishes him as a social realist. The political situation has been meticulously presented by Seth discussing about the Nehruvian world and the eminent political leaders of the nation of this period. A Suitable Boy functions as a political fable, showing the emerging polity of the newly independent India throwing light on various issues of communal disharmony narrating the real happening. Key Words: Transition, Conventions, Purdah System, Tandonite From here when we move to A Suitable Boy, we find that it is the story of a society in transition, of a country marching forward searching for new ways and means of stability. -

Stamps of India - Commemorative by Prem Pues Kumar [email protected] 9029057890

E-Book - 26. Checklist - Stamps of India - Commemorative By Prem Pues Kumar [email protected] 9029057890 For HOBBY PROMOTION E-BOOKS SERIES - 26. FREE DISTRIBUTION ONLY DO NOT ALTER ANY DATA ISBN - 1st Edition Year - 1st May 2020 [email protected] Prem Pues Kumar 9029057890 Page 1 of 76 Nos. YEAR PRICE NAME Mint FDC B. 1 2 3 1947 1 21-Nov-47 31/2a National Flag 2 15-Dec-47 11/2a Ashoka Lion Capital 3 15-Dec-47 12a Aircraft 1948 4 29-May-48 12a Air India International 5 15-Aug-48 11/2a Mahatma Gandhi 6 15-Aug-48 31/2a Mahatma Gandhi 7 15-Aug-48 12a Mahatma Gandhi 8 15-Aug-48 10r Mahatma Gandhi 1949 9 10-Oct-49 9 Pies 75th Anni. of Universal Postal Union 10 10-Oct-49 2a -do- 11 10-Oct-49 31/2a -do- 12 10-Oct-49 12a -do- 1950 13 26-Jan-50 2a Inauguration of Republic of India- Rejoicing crowds 14 26-Jan-50 31/2a Quill, Ink-well & Verse 15 26-Jan-50 4a Corn and plough 16 26-Jan-50 12a Charkha and cloth 1951 17 13-Jan-51 2a Geological Survey of India 18 04-Mar-51 2a First Asian Games 19 04-Mar-51 12a -do- 1952 20 01-Oct-52 9 Pies Saints and poets - Kabir 21 01-Oct-52 1a Saints and poets - Tulsidas 22 01-Oct-52 2a Saints and poets - MiraBai 23 01-Oct-52 4a Saints and poets - Surdas 24 01-Oct-52 41/2a Saints and poets - Mirza Galib 25 01-Oct-52 12a Saints and poets - Rabindranath Tagore 1953 26 16-Apr-53 2a Railway Centenary 27 02-Oct-53 2a Conquest of Everest 28 02-Oct-53 14a -do- 29 01-Nov-53 2a Telegraph Centenary 30 01-Nov-53 12a -do- 1954 31 01-Oct-54 1a Stamp Centenary - Runner, Camel and Bullock Cart 32 01-Oct-54 2a Stamp Centenary -

Civics National Civilian Awards

National Civilian Awards Bharat Ratna Bharat Ratna (Jewel of India) is the highest civilian award of the Republic of India. Instituted on 2 January 1954, the award is conferred "in recognition of exceptional service/performance of the highest order", without distinction of race, occupation, position, or sex. The award was originally limited to achievements in the arts, literature, science and public services but the government expanded the criteria to include "any field of human endeavour" in December 2011. Recommendations for the Bharat Ratna are made by the Prime Minister to the President, with a maximum of three nominees being awarded per year. Recipients receive a Sanad (certificate) signed by the President and a peepal-leaf–shaped medallion. There is no monetary grant associated with the award. The first recipients of the Bharat Ratna were politician C. Rajagopalachari, scientist C. V. Raman and philosopher Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, who were honoured in 1954. Since then, the award has been bestowed on 45 individuals including 12 who were awarded posthumously. In 1966, former Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri became the first individual to be honoured posthumously. In 2013, cricketer Sachin Tendulkar, aged 40, became the youngest recipient of the award. Though usually conferred on Indian citizens, the Bharat Ratna has been awarded to one naturalised citizen, Mother Teresa in 1980, and to two non-Indians, Pakistan national Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan in 1987 and former South African President Nelson Mandela in 1990. Most recently, Indian government has announced the award to freedom fighter Madan Mohan Malaviya (posthumously) and former Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee on 24 December 2014. -

Charismatic Leadership in India

CHARISMATIC LEADERSHIP IN INDIA: A STUDY OF JAWAHARLAL NEHRU, INDIRA GANDHI, AND RAJIV GANDHI By KATHLEEN RUTH SEIP,, Bachelor of Arts In Arts and Sciences Oklahoma State University Stillwater, Oklahoma 1984 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS December, 1987 1L~is \<1ql SLfttk. ccp. ';l -'r ·.' .'. ' : . ,· CHARISMATIC LEADERSHIP IN INDIA: A STUDY OF JAWAHARLAL NEHRU, INDIRA GANDHI, AND RAJIV GANDHI Thesis Approved: __ ::::'.3_:~~~77----- ---~-~5-YF"' Av~~-------; , -----~-- ~~-~--- _____ llJ12dJ1_4J:k_ll_iJ.4Uk_ Dean of the Graduate College i i 1291053 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to express sincere appreciation to Professor Harold Sare for his advice, direction and encouragement in the writing of this thesis and throughout my graduate program. Many thanks also go to Dr. Joseph Westphal and Dr. Franz van Sauer for serving on my graduate committee and offering their suggestions. I would also like to thank Karen Hunnicutt for assisting me with the production of the thesis. Without her patience, printing the final copy would have never been possible. Above all, I thank my parents, Robert and Ruth Seip for their faith in my abilities and their constant support during my graduate study. i i i TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. JAWAHARLAL NEHRU . 20 The Institutionalization of Charisma. 20 I I I . INDIRA GANDHI .... 51 InstitutionaliZ~tion without Charisma . 51 IV. RAJIV GANDHI ..... 82 The Non-charismatic Leader •. 82 v. CONCLUSION 101 WORKS CITED . 106 iv CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION The leadership of India has been in the hands of one family since Independence with the exception of only a few years.