Modi, Social Media, and Competitive Electoral Populism in India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

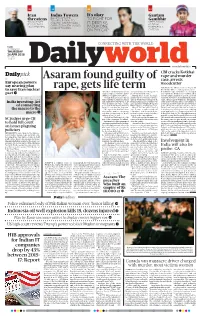

Asaram Found Guilty of Rape, Gets Life Term

10 11 01 12 Iran Indus Towers, It’s okay Gautam threatens BHARTI INFRATEL TO FIGHT FOR Gambhir TO QUIT NPT TO MERGE; DEAL TO IT: DEEPIKA STEPS DOWN IF US SCRAPS CREATE LISTED TOWER AS DELHI NUCLEAR DEAL OPERATOR WITH 163,000 PADUKONE DAREDEVILS MOBILE TOWERS ON PAY GAP CAPTAIN 4.00 CHANDIGARH THURSDAY 26 APR 2018 VOLUME 3 ISSUE 114 www.dailyworld.in CBI cracks Kotkhai dailypick rape-and-murder INTERNATIONAL Asaram found guilty of case, arrests European powers woodcutter say nearing plan rape, gets life term NEW DELHI The CBI has arrested a 25-year-old to save Iran nuclear woodcutter with a criminal past in connec- cused were convicted by the special ashrams in India and other parts of tion with the rape-and-murder of a teenaged 09 pact court hearing cases of crime against the world in four decades. schoolgirl in the Kotkhai area of Shimla, after children. It acquitted two others. During these years, he made his DNA sample matched the genetic material “Asaram was given life-long jail friends with the powerful. Old video found on the body of the victim and the crime T MUKHERJEE term, while his accomplices Sharad clips show him with politicians from scene, officials said on Wednesday. The findings and Shilpi were sentenced to 20 Bharatiya Janata Party as well as Con- of the agency will bring relief to the families of India investing: Art years in jail by the court,” public gress, including Narendra Modi, Atal five people arrested earlier by the state police of connecting prosecutor Pokar Ram Bishnoi told Bihari Vajpayee and Digvijay Singh. -

Anti-Corruption Movement: a Story of the Making of the Aam Admi Party and the Interplay of Political Representation in India

Politics and Governance (ISSN: 2183–2463) 2019, Volume 7, Issue 3, Pages 189–198 DOI: 10.17645/pag.v7i3.2155 Article Anti-Corruption Movement: A Story of the Making of the Aam Admi Party and the Interplay of Political Representation in India Aheli Chowdhury Department of Sociology, Delhi School of Economics, University of Delhi, 11001 Delhi, India; E-Mail: [email protected] Submitted: 30 March 2019 | Accepted: 26 July 2019 | Published: 24 September 2019 Abstract The Aam Admi Party (AAP; Party of the Common Man) was founded as the political outcome of an anti-corruption move- ment in India that lasted for 18 months between 2010–2012. The anti-corruption movement, better known as the India Against Corruption Movement (IAC), demanded the passage of the Janlokpal Act, an Ombudsman body. The movement mobilized public opinion against corruption and the need for the passage of a law to address its rising incidence. The claim to eradicate corruption captured the imagination of the middle class, and threw up several questions of representation. The movement prompted public and media debates over who represented civil society, who could claim to represent the ‘people’, and asked whether parliamentary democracy was a more authentic representative of the people’s wishes vis-à-vis a people’s democracy where people expressed their opinion through direct action. This article traces various ideas of po- litical representation within the IAC that preceded the formation of the AAP to reveal the emergence of populist repre- sentative democracy in India. It reveals the dynamic relationship forged by the movement with the media, which created a political field that challenged liberal democratic principles and legitimized popular public perception and opinion over laws and institutions. -

UTTAR PRADESH STATE POWER SECTOR EMPLOYEE's TRUST 24-Ashok Marg, Shakti Bhawan Vistar, Lucknow-226001

UTTAR PRADESH STATE POWER SECTOR EMPLOYEE'S TRUST 24-Ashok Marg, Shakti Bhawan Vistar, Lucknow-226001 GPF Number Generation Module Report Code : FP204 List Of GPF Number Alloted in Officer Cadre Date From : 01/04/2018 To : 31/03/2019 Sl. No. New GPF Number Name Father Name Designation Division Code , Name & Station 1 EB/O/10702 WALIUDDIN KHAN SRI ALLAH BUKSH AE 952 - ELECT CIV DISTR DIV-MEERUT 2 EB/O/10701 SHAHID MASHUQ SRI MASHUQ ALI AE 628A - ELECT WORKSHOP DIV-LUCKNOW 3 EB/O/10700 JAWAHAR LAL LATE BENI PRASAD OSD 992 - ACCOUNTS OFFICER HQ UPPCL- YADAV LUCKNOW 4 EB/O/10699 DINESH KUMAR LATE SHRI AE 390 - PARICHHA THERMAL POWER GUPTA KISHORA SHARAN PROJECT- JHANSI GUPTA 5 EB/O/10698 ALOK KHARE SRI ONKAR AAO 612 - ELECT DISTRIBUTION PRASAD KHARE CIRCLE-RAIBARELY 6 EB/O/10697 PAWAN KUMAR LATE SRI BABU AAO 166 - ZONAL ACCOUNTS OFFICER (TC)- GUPTA RAM GUPTA LUCKNOW 7 EB/O/10696 ANIL KUMAR LATE PRATAP SO 992 - ACCOUNTS OFFICER HQ UPPCL- SINGH NARAYAN SINGH LUCKNOW 8 EB/O/10695 PARAS NATH LATE TRIVENI AE 1111 - HQ UP JAL VIDUT NIGAM LTD.- YADAV YADAV LUCKNOW 9 EB/O/10694 BABU LAL LATE MEWA LAL AE 2004 - THERMAL POWER STATION OBRA PRAJAPATI "B"- OBRA 10 EB/O/10693 PAWAN KUMAR LATE SRI HARI AE 914A - ELECT DIST. DIV IV-SYANA, SINGH BULANDSHAHAR 11 EB/O/10692 KRISHAN PAL LATE RAM PAL AAO 577 - ELECT URBAN DISTR DIVSION(KD) -ALLAHABAD 12 EB/O/10691 SHIV ADHAR LATE DURGA AE 2004 - THERMAL POWER STATION OBRA PRASAD PAL "B"- OBRA 13 EB/O/10690 RAGHUPATI SRI RAM CHANDRA AE 2004 - THERMAL POWER STATION OBRA "B"- OBRA 14 EB/O/10689 JANAK DHARI LATE BUDHI RAM AE 2006 - TOWNSHIP ATPS OBRA- OBRA 15 EB/O/10688 RAKESH KUMAR LATE SRI MOTI LAL AE 390 - PARICHHA THERMAL POWER DWIVEDI DWIVEDI PROJECT- JHANSI 16 EB/O/10687 SATISH KUMAR LATE JAIRAM AE 2004 - THERMAL POWER STATION OBRA SINGH SINGH "B"- OBRA 17 EB/O/10686 YOGENDRA LATE THAN SINGH AE 489 - ELE DISTR DIVISION-I-BAREILLY SINGH 18 EB/O/10685 RAM SINGH SRI KRISHNA AE 2004 - THERMAL POWER STATION OBRA PRASAD SINGH "B"- OBRA 19 EB/O/10684 BUDH PRIYA SRI JASWANT AAO 426A - ELECT. -

India's Rape Culture: Urban Versus Rural

site.voiceofbangladesh.us http://site.voiceofbangladesh.us/voice/346 India’s Rape Culture: Urban versus Rural By Ram Puniyani While the horrific rape of Damini, Nirbhaya (December16, 2012) has shaken the whole nation, and the country is gripped with the fear of this phenomenon, many an ideologues and political leaders are not only making their ideologies clear, some of them are regularly putting their foots in mouths also. Surely they do retract their statements soon enough. Kailash Vijayvargiya, a senior BJP minister in MP’s statement that women must not cross Laxman Rekha to prevent crimes against them, was disowned by the BJP Central leadership and he was thereby quick enough to apologize to the activists for his statement. But does it change his ideology or the ideologies of his fellow travellers? There are many more in the list from Abhijit Mukherjee, to Mamata Bannerji, Asaram Bapu and many more. The statement of RSS supremo, Mohan Bhagwat, was on a different tract as he said that rape is a phenomenon which takes place in India not in Bharat. For India the substitute for him is urban areas and Bharat is rural India for him. As per him it is the “Western” lifestyle adopted by people in urban areas due to which there is an increase in the crime against women. “You go to villages and forests of the country and there will be no such incidents of gang rape or sex crimes”, he said on 4th January. Further he implied that while urban areas are influenced by Western culture, the rural areas are nurturing Indian ethos, glorious Indian traditions. -

NDTV Pre Poll Survey - U.P

AC PS RES CSDS - NDTV Pre poll Survey - U.P. Assembly Elections - 2002 Centre for the Study of Devloping Societies, 29 Rajpur Road, Delhi - 110054 Ph. 3951190,3971151, 3942199, Fax : 3943450 Interviewers Introduction: I have come from Delhi- from an educational institution called the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies (give your university’s reference). We are studying the Lok Sabha elections and are interviewing thousands of voters from different parts of the country. The findings of these interviews will be used to write in books and newspapers without giving any respondent’s name. It has no connection with any political party or the government. I need your co-operation to ensure the success of our study. Kindly spare some ime to answer my questions. INTERVIEW BEGINS Q1. Have you heard that assembly elections in U.P. is to be held in the next month? 2 Yes 1 No 8 Can’t say/D.K. Q2. Have you made up your mind as to whom you will vote during the forth coming elections or not? 2 Yes 1 No 8 Can’t say/D.K. Q3. If elections are held tomorrow it self then to whom will cast your vote? Please put a mark on this slip and drop it into this box. (Supply the yellow dummy ballot, record its number & explain the procedure). ________________________________________ Q4. Now I will ask you about he 1999 Lok Sabha elections. Were you able to cast your vote or not? 2 Yes 1 No 8 Can’t say/D.K. 9 Not a voter. -

'India Against Corruption'

Frontier Vol. 44, No. 9, September 11-17, 2011 THE ANNA MOMENT ‘India Against Corruption’ Satya Sagar TO CALL ANNA HAZARE'S crusade against corruption a 'second freedom movement' may be hyperbole but in recent times there has been no mass upsurge for a purely public cause, that has captured the imagination of so many. For an Indian public long tolerant of the misdeeds of its political servants turned quasi-mafia bosses this show of strength was a much-needed one. In any democracy while elected governments, the executive and the judiciary are supposed to balance each other's powers, ultimately it is the people who are the real masters and it is time the so-called 'rulers' understand this clearly. Politicians, who constantly hide behind their stolen or manipulated electoral victories, should beware the wrath of a vocal citizenry that is not going to be fooled forever and demands transparent, accountable and participatory governance. The legitimacy conferred upon elected politicians is valid only as long as they play by the rules of the Indian Constitution, the laws of the land and established democratic norms. If these rules are violated the legitimacy of being 'elected' should be taken away just as a bad driver loses his driving license or a football player is shown the red card for repeated fouls. The problem people face in India is clearly that there are no honest 'umpires' left to hand out these red cards anymore and this is not just the problem of a corrupt government or bureaucracy but of the falling values of Indian society itself. -

From Secular Democracy to Hindu Rashtra Gita Sahgal*

Feminist Dissent Hindutva Past and Present: From Secular Democracy to Hindu Rashtra Gita Sahgal* *Correspondence: secularspaces@ gmail.com Abstract This essay outlines the beginnings of Hindutva, a political movement aimed at establishing rule by the Hindu majority. It describes the origin myths of Aryan supremacy that Hindutva has developed, alongside the campaign to build a temple on the supposed birthplace of Ram, as well as the re-writing of history. These characteristics suggest that it is a far-right fundamentalist movement, in accordance with the definition of fundamentalism proposed by Feminist Dissent. Finally, it outlines Hindutva’s ‘re-imagining’ of Peer review: This article secularism and its violent campaigns against those it labels as ‘outsiders’ has been subject to a double blind peer review to its constructed imaginary of India. process Keywords: Hindutva, fundamentalism, secularism © Copyright: The Hindutva, the fundamentalist political movement of Hinduism, is also a Authors. This article is issued under the terms of foundational movement of the 20th century far right. Unlike its European the Creative Commons Attribution Non- contemporaries in Italy, Spain and Germany, which emerged in the post- Commercial Share Alike License, which permits first World War period and rapidly ascended to power, Hindutva struggled use and redistribution of the work provided that to gain mass acceptance and was held off by mass democratic movements. the original author and source are credited, the The anti-colonial struggle as well as Left, rationalist and feminist work is not used for commercial purposes and movements recognised its dangers and mobilised against it. Their support that any derivative works for anti-fascism abroad and their struggles against British imperialism and are made available under the same license terms. -

Science and Rising Nationalism in India

COMMENT BOOKS & ARTS of conservatism has long mingled with Christian fundamentalism and the rejection of evolution. But as the examples in Holy Science show, the burgeoning complexity of this fusion in India is notable. Ancient India abounded in scientific advances, in fields from astronomy and mathematics to metallurgy and surgery. The DIBYANGSHU SARKAR/AFP/GETTY DIBYANGSHU Sanskrit text Sushruta Samhita, dated to the first millennium bc, discusses techniques for skin grafts and nose reconstruction. These achievements, along with traditional Indian knowledge systems, were egregiously sidelined during colonial rule. Yet some nationalist rhetoric overstates or distorts history. Subramaniam shows how modern science has been bolted to Hindu mythol- ogy: Modi has posited, for example, that the elephant-headed deity Ganesha was a prod- uct of ancient cosmetic surgery. Other claims have been made for the current relevance of ancient practices. For instance, Modi has made speeches declaring that yoga can help tackle climate change by nurturing a social conscience. At the heart of Holy Science are several case studies examining the interplay of biology, public policy and ancient traditions in today’s India, which Subramaniam frames as “bio- nationalism”. One is the marketing of vaastu Preparations for a rally in favour of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi in Kolkata in April 2019. shaastra, literally the ‘science of architecture’, a tradition not unlike Chinese feng shui that POLITICS originated in the Vedas — the earliest Hindu scriptures, dating back more than three mil- lennia. This belief system holds that siting rooms and entrances in certain ways bestows Science and rising harmony and encourages well-being. -

India: the Weakening of the Congress Stranglehold and the Productivity Shift in India

ASARC Working Paper 2009/06 India: The Weakening of the Congress Stranglehold and the Productivity Shift in India Desh Gupta, University of Canberra Abstract This paper explains the complex of factors in the weakening of the Congress Party from the height of its power at the centre in 1984. They are connected with the rise of state and regional-based parties, the greater acceptability of BJP as an alternative in some of the states and at the Centre, and as a partner to some of the state-based parties, which are in competition with Congress. In addition, it demonstrates that even as the dominance of Congress has diminished, there have been substantial improvements in the economic performance and primary education enrolment. It is argued that V.P. Singh played an important role both in the diminishing of the Congress Party and in India’s improved economic performance. Competition between BJP and Congress has led to increased focus on improved governance. Congress improved its position in the 2009 Parliamentary elections and the reasons for this are briefly covered. But this does not guarantee an improved performance in the future. Whatever the outcomes of the future elections, India’s reforms are likely to continue and India’s economic future remains bright. Increased political contestability has increased focus on governance by Congress, BJP and even state-based and regional parties. This should ensure improved economic and outcomes and implementation of policies. JEL Classifications: O5, N4, M2, H6 Keywords: Indian Elections, Congress Party's Performance, Governance, Nutrition, Economic Efficiency, Productivity, Economic Reforms, Fiscal Consolidation Contact: [email protected] 1. -

“Product Positioning of Patanjali Ayurved Ltd.”

“PRODUCT POSITIONING OF PATANJALI AYURVED LTD.” DR. D.T. SHINDE SAILEE J. GHARAT Associate Professor Research Scholar Head, Dept. of Commerce & Accountancy K.B.P. College, Vashi, Navi K.B.P.College, Vashi, Navi Mumbai Mumbai (MS) INDIA (MS) INDIA In today’s age there is tough competition in the field of production and marketing. Instead of that we are witnessing the Brand positioning by Patanjali. Currently, Patanjali is present in almost all categories of personal care and food products ranging from soaps, shampoos, dental care, balms, skin creams, biscuits, ghee, juices, honey, mustard oil, sugar and much more. In this research paper researcher wants to study the strategies adopted by Patanjali. Keywords: Patanjali, Brand, Positioning, PAL. INTRODUCTION Objectives of the study: To study Patanjali as a brand and its product mix. To analyze and identify important factors influencing Patanjali as a brand. To understand the business prospects and working of Patanjali Ayurved Ltd To identify the future prospects of the company in comparison to other leading MNCs. Relevance of the study: The study would relevant to the young entrepreneurs for positioning of their business. It would also open the path for various research areas. Introduction: Baba Ramdev established the Patanjali Ayurved Limited in 2006 along with Acharya Balkrishna with the objective of establishing science of Ayurveda in accordance and coordinating with the latest technology and ancient wisdom. Patanjali Ayurved is perhaps the DR. D.T. SHINDE SAILEE J. GHARAT 1P a g e fastest growing fast-moving-consumer goods firm in India with Annual revenue at more than Rs 2,000 crore. -

Page14.Qxd (Page 1)

SATURDAY, APRIL 27, 2019 (PAGE 14) DAILY EXCELSIOR, JAMMU Modi lists Rs 2.5 cr worth assets NYAY scheme will not be strain on middle class pocket: Rahul SAMASTIPUR (Bihar), Apr 26: has not Modi looted you a lot. VARANASI, Apr 26: Lakhs of crores have been Congress president Rahul Prime Minister Narendra Modi has assets worth Rs 2.5 crore gifted to thieves like Nirav Modi, Gandhi on Friday called the Mehul Choksi and Vijay Mallya including a residential plot in Gujarat's Gandhinagar, fixed NYAY scheme a surgical strike by the chowkidar (watchman an deposits of Rs 1.27 crore and Rs 38,750 cash in hand, according to on poverty and asserted that the epithet the Prime Minister uses his affidavit filed with the Election Commission today. proposed minimum income for himself). Public money to the Modi has named Jashodaben as his wife and declared that he guarantee programme was not tune of 5.55 lakh crore has been has an M.A. degree from Gujarat University in 1983. The affidavit populist but based on sound eco- siphoned off by 15 persons close said he is an arts graduate from Delhi University (1978). He passed nomics. to Modi, Gandhi alleged. SSC exam from Gujarat board in 1967, it said. Gandhi also sought to allay Bihar was promised a spe- He has declared movable assets worth Rs 1.41 crore and apprehensions of the middle cial package, besides there were immovable assets valued at Rs 1.1 crore. class saying he guaranteed that promises of two crore jobs, Rs The Prime Minister has invested Rs 20,000 in tax saving infra the salaried people will have to 15 lakh into the accounts of all bonds, Rs 7.61 lakh in National Saving Certificate (NSC) and pay not a single paisa from their poor, Gandhi recalled, adding pockets to fund the Nyuntam another Rs 1.9 lakh in LIC policies. -

An Indian Summer: Corruption, Class, and the Lokpal Protests

Article Journal of Consumer Culture 2015, Vol. 15(2) 221–247 ! The Author(s) 2013 An Indian summer: Reprints and permissions: sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav Corruption, class, and DOI: 10.1177/1469540513498614 the Lokpal protests joc.sagepub.com Aalok Khandekar Department of Technology and Society Studies, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, Maastricht University, The Netherlands Deepa S Reddy Anthropology and Cross-Cultural Studies, University of Houston-Clear Lake, USA and Human Factors International Abstract In the summer of 2011, in the wake of some of India’s worst corruption scandals, a civil society group calling itself India Against Corruption was mobilizing unprecedented nation- wide support for the passage of a strong Jan Lokpal (Citizen’s Ombudsman) Bill by the Indian Parliament. The movement was, on its face, unusual: its figurehead, the 75-year- old Gandhian, Anna Hazare, was apparently rallying urban, middle-class professionals and youth in great numbers—a group otherwise notorious for its political apathy. The scale of the protests, of the scandals spurring them, and the intensity of media attention generated nothing short of a spectacle: the sense, if not the reality, of a united India Against Corruption. Against this background, we ask: what shared imagination of cor- ruption and political dysfunction, and what political ends are projected in the Lokpal protests? What are the class practices gathered under the ‘‘middle-class’’ rubric, and how do these characterize the unusual politics of summer 2011? Wholly permeated by routine habits of consumption, we argue that the Lokpal protests are fundamentally structured by the impulse to remake social relations in the image of products and ‘‘India’’ itself into a trusted brand.